People Soup

Audrey Schmidt

Suicidal Oil Piglet, an unusual gallery name for which there is no given explanation, opened earlier this year in Coburg, Melbourne, by co-founders and artists Calum Lockey and Zac Segbedzi. Prior to SOP’s opening, the duo ran the website Melbourne Offsite Index with Hana Earles from 2015-6; documenting offsite shows staged in environments ranging from parked cars to empty apartments, organised by themselves and a cohort of like-minded collaborators. In its wake, SOP has provided a physical space to accommodate exhibition ideas that were necessarily limited or made impossible by the offsite one-day context. In many ways, SOP continues the ‘offsite’ mentality in an otherwise fairly traditional ‘onsite’ space, by showing artists who are seldom shown in larger institutional contexts ranging from emerging to established.

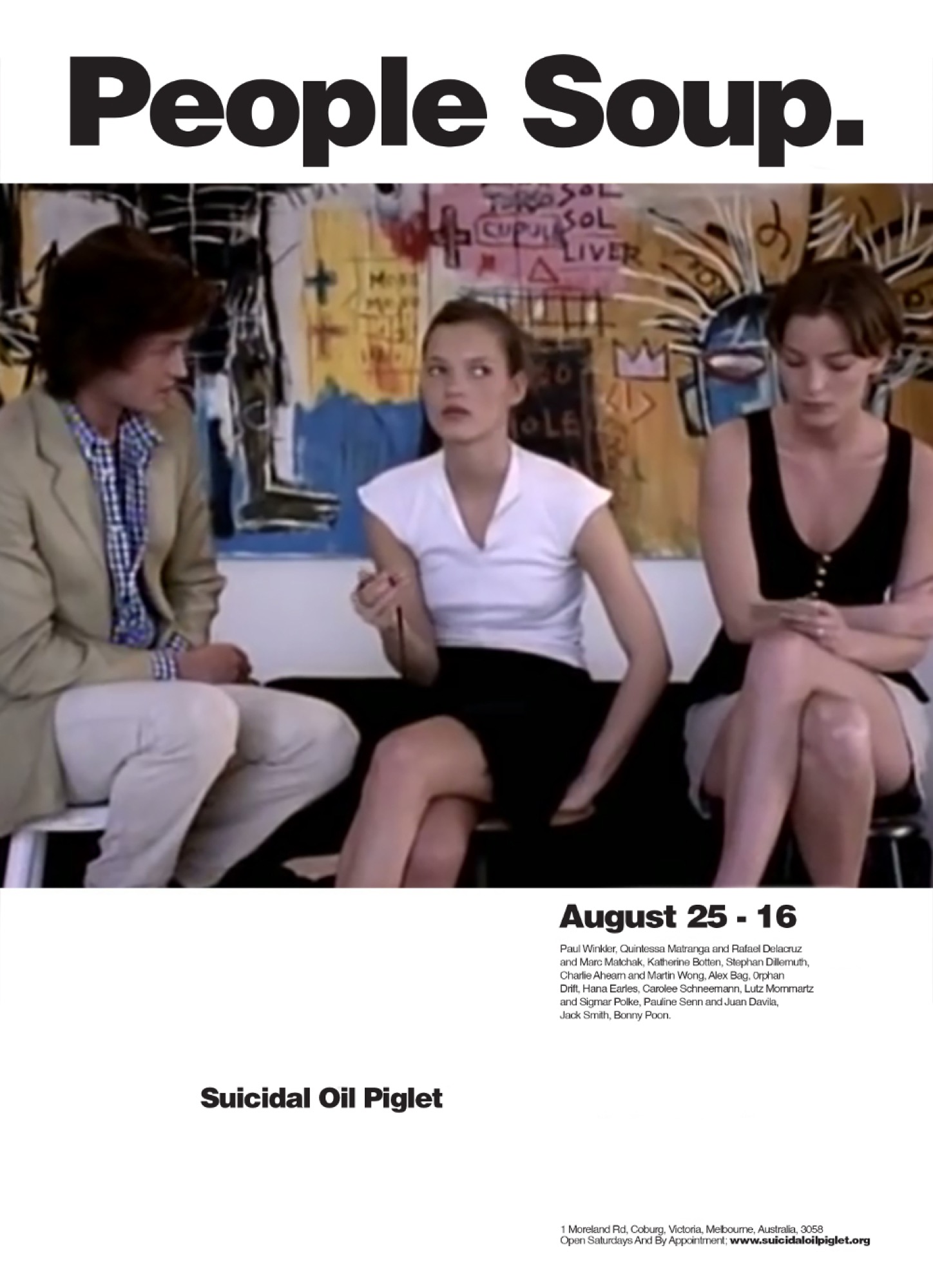

Curated by Lockey, SOP’s sixth exhibition takes the form of a film programme entitled People Soup that is advertised as ‘works by and about artists: 1963 to 2017.’ The gallery’s street-facing windows were lined with black garbage bags, and inside three rows of four chairs, cable-tied together, faced the east wall of the gallery where the films were to be projected, playing one after the other, creating a makeshift cinema experience in movie-marathon tradition. The popping of a small, retro-red, portable popcorn machine at the gallery’s entrance, presumably bought for the occasion, was the only sound that interrupted the soundscapes of the films on show.

The south wall featured three identical exhibition posters pasted onto it, mimicking the big-budget ‘rock poster’ advertising of stadium live music shows and state-funded art exhibitions. The poster itself features a still from Katharina Otto-Bernstein’s documentary Beautopia (1998), picturing Kate Moss being interviewed by Daniel and Lucy de la Falaise in front of a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting. Although not featured in the People Soup programme, the interplay of fashion, art, celebrity and posturing exemplified the themes of the opening night’s programme.

Paris-based Canadian artist, Bonny Poon, had one of the few feature-length works on show with Beautiful Balance (2016), which ran for just over an hour. Set in Germany’s financial centre, Frankfurt am Main, the film follows a cast of artists interchangeably playing the roles of characters Whitney and Taylor as they have flaccid MDMA sex in hotel rooms, banal conversations about work and exercise amongst footage of a Boiler Room day-party (and other such everyday euro-bohemian lifestyle activities). Combining HDCAM and iPhone footage, jump-cutting from one interaction to another seemingly unrelated one, Beautiful Balance has the feel of the fragmented memories of a drug-fuelled bender, kick-on and come-down—beginning with a boring date. One of the pithiest lines in Poon’s film was ‘nobody has an interesting life’, which came to define the portrait painted of two lovers traipsing through neoliberal hegemony and millennial ennui. The interchangeability of the characters and their actors came to represent a disenchanted life of enduring uniformity under these conditions.

Beautiful Balance was followed by German-Australian Paul Winkler’s experimental Turmoil (2000) and Hana Earles’ $1070 (2017). The latter included Earles in a t-shirt inscribed with ‘world peace’, monotonously reading Bernadette Corporation’s Reena Spaulings (2005) in a bright yellow plastic wig in front of the logos for UberEats and Vice whilst smoking a cigarette. Bernadette Corporation described Reena Spaulings as ‘a collective experiment in which the only thing shared is the lack of uniqueness’ and this rings true in $1070 : positioning the re-emergence of ‘art as social practice’, activism, and the utopian vision of collectivity as monetised brands along with VICE and UberEats. It is also a sentiment that matches the disenchantment of Beautiful Balance and raises it to a bleak, albeit enormously droll, pessimism.

Quintessa Matranga, Rafael Delacruz and Marc Matchak’s collaborative film, Lebenswirklichkeit (2017), presented many of the same concerns as Poon and Earles. Lebenswirklichkeit, one of those many German words that have no direct English equivalent, loosely translates as ‘reality of life’ or ‘everyday reality’. The title reflects a German theme running throughout the film and People Soup more broadly, ironically questioning the persistent influence of, and obsession with, Germany’s cultural legacy (which feels particularly relevant post documenta 14). Considering SOP’s previous exhibition of German painters entitled Der Schneckentraum—and with Stephen Dillemuth’s Elbsandsteingebirge 1789–1848 (1994) as well as Lutz Mommartz and Sigmar Polke’s The Beautiful Sigmar (1971) set to be screened after opening night—this curatorial commentary became even more palpable.

Set to a soundtrack of lo-fi pop rock and featuring the same ‘mumblecore’ approach to low-budget filmmaking as Poon, Lebenswirklichkeit sees a group of young New York artists and creatives (in addition to SOP co-founder Zac Segbedzi) performing a barely fictional representation of themselves. Duncan, our protagonist, is vaguely ambitious but ultimately lethargic. While his approach to his ‘day-job’ at a Children’s Centre is particularly lacklustre, he takes initiative in approaching the unimpressed fictional (and presumed to be established) artist ‘Arthur Basel’ for work as an artist’s assistant. Following Duncan through a series of interactions with art ‘experts’, I was forced to question what it means to be fluent in contemporary art discourse and ‘expert culture’ in a contemporary Australia that is heavily impacted by globalisation. The suggestions drawn from this discourse regularly pointed back to the German art elite—most notably to the prestigious art school Städelschule, which is home to more international students than local ones.

Duncan eventually gets fired from his day job as he’s caught via Instagram attending an exhibition when he was meant to be at work, ultimately culminating in him suing his employers for unfair dismissal. The resultant court case reminded me, however much abbreviated in its screen-time, to A Crime Against Art (2007). Directed by Hila Peleg and filmed by four camera crews, A Crime Against Art professed to promote a move away from market structures and commercial spectacle through the dematerialised art object and the expanded field of artistic practice and ‘site.’ The film documented the performance work The Trial (also 2007), which was a collaborative effort attributed to Anton Vidokle and Tirdad Zolghadr, featuring a line-up of prominent, European artworld figures on trial for such crimes as being in ‘collusion with the bourgeoisie.’

Despite its formal shift from the art object and critique of market structures, A Crime Against Art, with its cast of art stars, camera crews and funding from e-flux, was immediately socially valorised by its elite target audience. The Trial was also directly funded by Europe’s largest annual contemporary art fair, ARCO, where it was initially staged. By contrast, Lebenswirklichkeit highlights the more banal ‘everyday’ aspects of entrepreneurial creative living that stand convicted of impeding artistic production for lesser-known, emerging artists and creatives. Importantly, this work demonstrates an inability to escape the market and social structures governing our capacity to produce, exhibit and circulate art in the first place. Lebenswirklichkeit was a truly entertaining mockery of these structures, of A Crime Against Art, and of the unlikely event that you’d be in a position to take your employer to court as a blasé young creative.

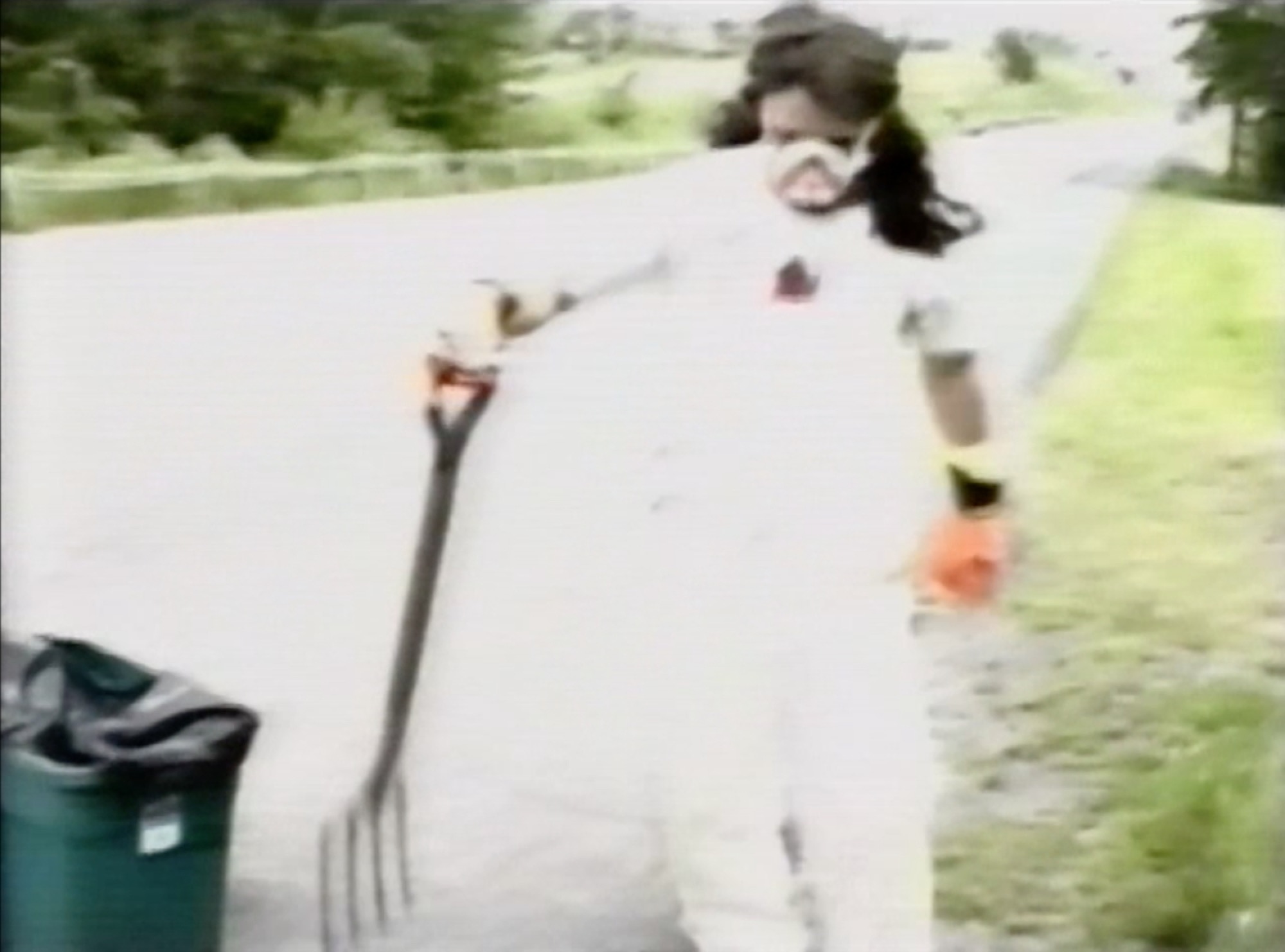

Lebenswirklichkeit was followed by Charlie Ahern’s Portrait of Martin Wong (1998), depicting the squalor of the talented (and posthumously revered) artist’s live-in New York studio, where the reality of the artist’s lifestyle was really driven home. The final film I saw was Alex Bag’s The Artist’s Mind (1996), which takes the form of a ‘day-in-the-life- of’ TV show documenting contemporary visual artists. The Artist’s Mind follows aspiring artist Damien Bag, tinny in hand, as he meticulously takes the viewer through his daily routine of waking up (in what looks like a squat), eating breakfast, making it to Walmart by 9 and eating lunch at McDonalds before collecting road-kill. In a clear reference to Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child Divided (1993), which won the Turner Prize in 1995, he later places his findings in a glass tank filled with formaldehyde, gagging and poking it as the animal carcass bloats and disintegrates. Shirtless in his overalls and set to a horror-like classical musical score, the aspiring artist appears more homicidal country hick than multi-million dollar career-artist.

People Soup is a show about artists making art about artists, but more than that, it is about the changing state of the market and subjectivity in relation to ‘art as social practice’ under neoliberal globalisation. The inherent contradictions and uncertain future of the unsteady relationship between these elements is deftly expressed through SOP’s film programme with a great deal of humour. With its suite of films shown back-to-back on one projector, the exhibition encouraged a durational engagement with the works. And, after almost six hours of viewing, the future definitely didn’t feel bright, but at least it was self-aware.

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and Melbourne Personality.

Title image: Hana Earles, $1070, 2017, 08:00.)