Our Place: 20 Years of Town Hall Gallery

Jarrod Zlatic

To celebrate its twentieth birthday, the Town Hall Gallery in Hawthorn is holding the exhibition Our Place—the anniversary providing a good excuse for a greatest hits showing of the gallery’s collection. The “our place” in this instance is the remit of the City of Boroondara that includes Kew, Balwyn, Camberwell, and Hawthorn. That these suburbs are amongst the wealthiest in Melbourne may account for the relative strength of the gallery’s permanent collection.

For the collection we can thank former Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett and the machinations of state politics; Kennett’s drastic and controversial amalgamation of councils in 1994 resulted in the combination of formerly separate collections into one. The municipal consolidations also voided the Hawthorn Town Hall of its former purpose, until its reconstitution as a function space and gallery, a further eighteen-million-dollar conversion in 2013 resulting in the Hawthorn Arts Centre. Though Our Place isn’t framed by any explicit historical or chronological explications about the gallery or the local area. Rather, works from the collection are grouped together by three nebulous propositions—people, places, and perspectives.

I actually entered at the “end” of the exhibition (though the gallery’s layout is something of an ouroboros, so both time and space circle around anyway). This is the room designated by the theme Places; the majority of the works here are landscapes, emphasised by the long wall painted pea green. The final trio of paintings in the exhibition is something of a beginning in that they are among the oldest works in the show. There is a typical Max Meldrum and an askew impressionist work by A M E Bale, both good examples of exploratory early twentieth-century landscape painting. This section also displays Our Place’s hero painting, John Bracks’s The Yarra at Kew (1946), which adorns the exhibition promotions and a tote bag available at the front desk. It is a very early and uncharacteristic work by Brack, who is best known for his dry, inexpressionism. While Brack is a decidedly post-war artist, The Yarra at Kew exemplifies first wave Melbourne modernist painting in both its style and theme, treating the Yarra as a local Aix-en-Provence. Though the incursion of Boyd-like builds into the hillside does point toward Brack’s typical preoccupation with urban life. Student work, sure, but satisfying in its slightness.

Brack was part of a small, informal circle of modernist painters from around Kew that believed painting plein air was uncomplicated, still contemporary (just), unironic (yet to be). Headed up by Fred Williams and Ian Armstrong, in 1946 this group rented a shack in rural Lilydale as a quasi-artist camp so as to undertake outdoor painting. In Our Place, Williams has a late, large-scale watercolour, Mount Killie Crankie (Flinders Island) (1980), a lunar-like surface in soft washes of silvery-purplely grey that is enlivened by splotches of colour in the foreground. Like many of his innumerable watercolours, Mount Killie Crankie has a delicacy and lightness of touch that too often became absent in Williams’s oil paintings after about 1970. Armstrong is present also, providing one of the highlights of the show in a trio of understated, minor-key urban landscapes (a sketchy gouache sketch from 1969, and a print each from the 1980s and 1990s). They are all repeated attempts across thirty years to depict Hawthorn’s Barkers Road at night, the rain and puddles cut by the glare of headlights.

If Places is concerned with tradition, the opening room Perspectives is preoccupied with the contemporary. While the works are disparate, they are united through a vague thread of abstraction. There is a sense of space in this room’s arrangement, unlike the others that suffer from a strangling uniform hang. The emblematic figure here is the painter Helen Maudsley. Unlike her husband John Brack who, in the adjacent room, stages a last stand for older strands of genre and an ethos of realism, Maudsley’s works are utterly artificial exercises in pure design. It was perhaps as a compliment that Brack once remarked to Maudsley how fortunate she was that her art didn’t require a model to work from. While Brack remained “classical” in his approach and continued to make figure nude studies, Maudsley worked within the virtualised space inaugurated by cubism.

Here Maudsley has two paintings hanging side by side. There is the forbiddingly titled Permission and Gender. ‘It’s not a Competition; it’s to Do, and be Validated.’ ‘No it’s not; it’s Who Rules. I Am, There, but am Not, Here.’ The Male to the Female; You can Do only what I allow you to. The Female to the Female; You’re a Nothing and I will Stamp You Out. In 16th Century Italy, ‘The Young Man in the Hat’ is not part of this. (2015). The work is typical of Maudsley’s practice: game-like, with the coy hard-edgedness offset by her signature palette of eternal evening mauve. In the second, much earlier painting, The Wonderful Diversion (1958), plant forms appear to have been taken from botanical prints rather than from faithful observation, and light shines as both sun and studio lamp at either end of the composition. Maybe The Wonderful Diversion is a gentle joke about the painter’s dedication to observation—perhaps it is not that painting itself is a diversion, but that the weight of tradition distracts painters from getting on with the actual job of painting?

In the accompanying essay, the curators stress that Our Place demonstrates the breadth of the gallery’s collection. There is certainly a large amount of work on display. I counted just under fifty all up. While there are individually quite a few good pieces, unfortunately little dialogue occurs between these works. This lack of cohesion is emphasised by the scattershot quality of the accompanying wall texts. For example, I was puzzled by the inclusion of Southbound Flight (1986) by Yvonne Audette, whom I think of as a quintessentially Sydney painter. The wall-text explains that Audette was born in Sydney, OK, and the painting was originally exhibited in Castlemaine, OK, but nothing else. I had to go Googling to find out that the work was a very recent acquisition—an auction result from 2021 indicates a $41,727 acquisition to be exact—and that Audette has been living in Melbourne since 1969, and more relevantly, teaching the Sunday morning drawing classes at the Hawthorn Arts Society since 1993. The reluctance by the curators to provide any level of historicising or contextualisation is not necessarily a problem, but the awkward flow between individual works deflates whatever visual correspondences are here. This in turn lends to the quality of a very professional jumble sale or auction catalogue. For all the invocations of the local, for example, I was struck by how little of the area came through beyond mere pictures. The lack of even token engagement with Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung notions of place is one obvious criticism. Yet even for all the urban views here—which I personally found recognisable, familiar even—I was still afflicted by the feeling of rootlessness, one that permeates the show. Less would have meant much more here.

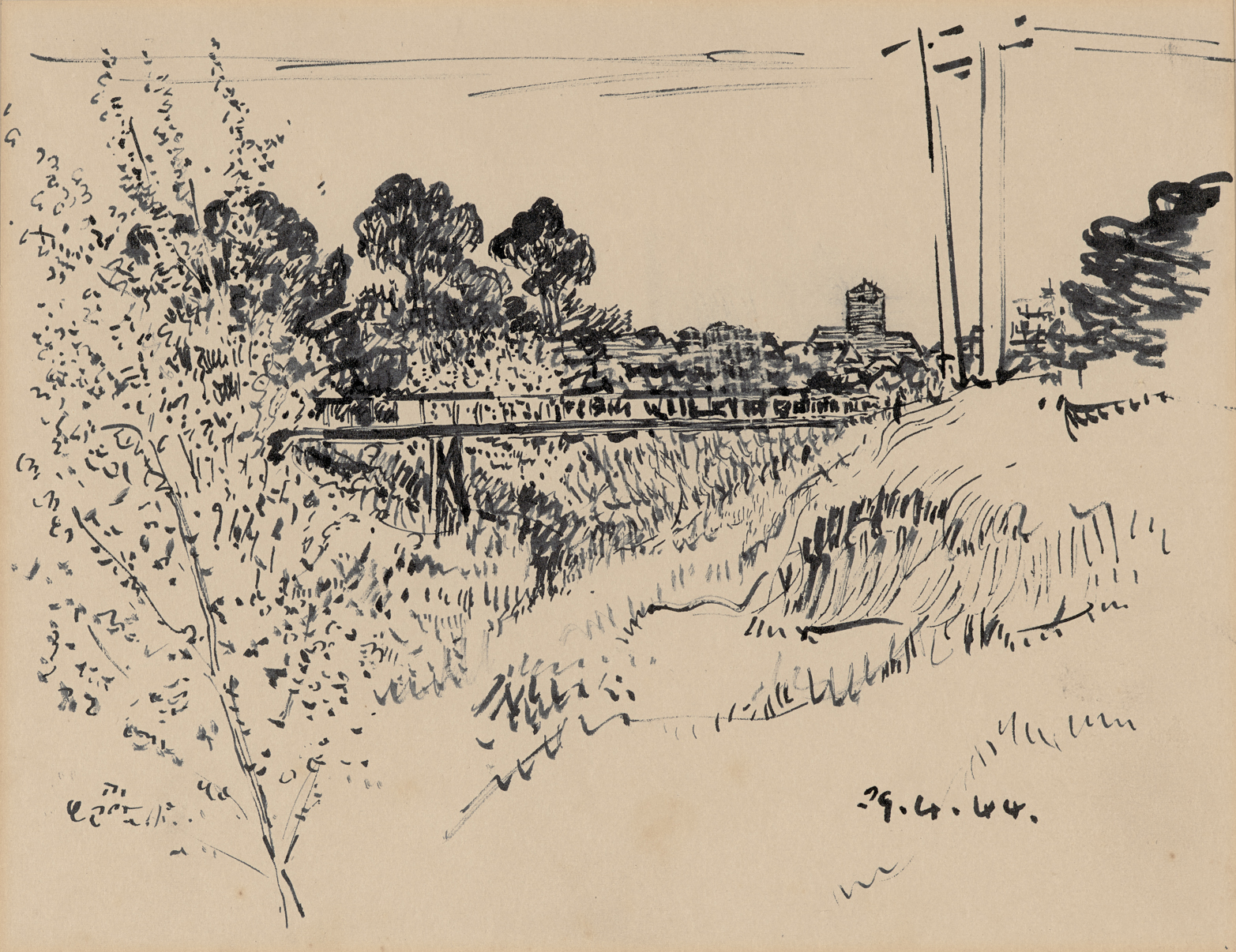

The upside to the curatorium’s drive to fill space is that alongside the better-known names are works by minor artists, the passing fancies one hopes to find hidden amongst council collections. Perhaps the most minor work of all is by James Minogue, who was an original follower of Meldrum and member of the Monstalvat artist colony (though more iconically he designed the Skipping Girl Vinegar logo in neighbouring Abbotsford when he was nine-years old). Gardiner’s Creek, Glen Iris (1944) is an ink sketch of the untended land near the bridge that crosses the creek. The scene is built from snaking lines and dashes; overhead the powerlines are so briefly alluded to that they could be clouds. It has a freeness and nothingness like the small weeds and flowers that grow amongst the long grass alongside these urban creeks—a barely there feeling. There is an impressive unity in Gardiner’s Creek, Glen Iris in how marginality is encompassed in theme, style, and ethos. Radiating simplicity, I found it cut through everything else in the show.

That professionals and amateur artists rubbed shoulders in Australia until the beginnings of “contemporary art” in the early 1960s is a fact often overlooked. The preferred bifurcation is usually independent versus institution, or modernism versus tradition. Though if one goes looking for these early Australian modernists, or indeed any type of exhibiting artists or groups, background training was not especially a barrier to entry. It seems that council galleries—with their community engagement requirements with exhibitions like Our Place—remain the ideal place to link these now separate strands. The accompanying exhibition essay does note how the collection is a repository of both contemporary and community art. Though due to the greatest hits nature of the selections, the definition of community artist here is limited. There are certainly artists from the community (I think practically all artists included are) but nothing in the vein of “community arts”—e.g., non-professionals, Sunday-type painters, arts therapy groups and so on, examples of which can be found in the Town Hall’s collection (fully digitised and available online).

To find community art one must look to the corridor adjacent to the main gallery. Here, there is an inaugural summer salon celebrating a different milestone—ten years of the Town Hall Gallery’s community exhibitions program. Somewhat negligently I didn’t make a note of any artists, but this was difficult as there were no wall-texts so the artists and works were all rendered nameless (unless one could be bothered with cumbersome QR codes, which, as a rule, I am not). There are rough, therapeutic style landscapes, but also commercial abstraction and accomplished photo-realism.

Returning to Our Place, the contemporary art—work by professional artists, maybe gallery represented—is no less a mixed bunch than out in the corridor. There are some good works; I liked Andrew Mezei’s Dominion (2012) in the same way I like fantasy novel cover illustrations, Cassie Leatham’s clay midden jars had charm, Samara Adamson-Pinczewski’s geo-ab paintings are inoffensive (though I found the sculpture garish). I came around to John Young Zerunge’s sprawling 1886: The Worlds of Lowe Kong Meng and Jong Ah Siug (2015) (incidentally or not, I kept receiving ads for his account on Instagram quite a few times after visiting). As for Emily Floyd’s kindergarten constructivism, I can never decide how I feel about it.

The demarcation between Our Place and the summer salon doesn’t seem to hinge on any question of ability but, instead, on diverging degrees of narrativity. Certainly, the long after-life of the landscape painting exhibited in Our Place can be found in the community art in the corridor, but it is ultimately adrift. It is not addressed towards any history or present of “art,” nor its institutions. Out in the corridor, the artworks are beyond the point or purpose of art criticism as such. Yet works could have been swapped between the two exhibitions and it likely would have made little difference. In fact, the inclusion of community art from the collection would have strengthened the show and its evocation of place.

It is not that there is no amateur artmaking included in Our Place. But the sole example is not even an artwork per se, but rather an artless family photo of a group of tree pruners taken from the Town Hall Gallery’s historical collection. Appropriately, the mounting is inelegant and accidental—the ripped photo has been stuffed into an oversized floating frame, sitting awkwardly at the bottom of the mount. This strange image was even one of my favourite works in the show. Out of everything, it speaks the most to the gallery and its anniversary celebration: the anonymous council workers up on their ladders amongst the branches working towards civic upkeep. They are not unlike the anonymous arts administrators at work behind their laptops, running the Town Hall Gallery with a similar mission of civic uplift, curating shows with the same regularity with which trees need pruning.

Jarrod Zlatic is a musician and critic from Melbourne.