Open World

Toyah Webb

I begin writing this review by not writing: I pick my nails; I go to the IGA; I eat a samosa chaat from Harris Park. Standing outside Pari, I find myself thinking about Tāmaki Makaurau’s 2020 lockdown and my sudden obsession with computer games. Driven by some ineffable desire, I spent hours scrolling Trade Me—Aotearoa’s superior Gumtree—for a cheap PC, just so I could run Elder Scrolls’ Morrowind, an early open-world RPG that I used to play with my cute neighbour; I installed Sims but quickly realised I could make Single Serve Scramble Eggs irl; I downloaded IMVU so that I could go virtual clubbing with friends in Germany. But the game that stuck was Myst. Released for Macintosh in 1993, Myst has no tutorial, no quest guide, no objectives, no non-player characters, no obvious source of conflict. Instead, the player is left to explore a pixelated island, from where—through a combination of logic and extreme patience—they might travel through portals to other worlds. In a locked-down city, these virtual worlds represented an intoxicating possibility.

Maybe this is why I am so taken with Pari’s Open World. Curated by co-directors Brenton Alexander Smith, Jane Asher, Joel Spring, and Kalanjay Dhir, the show presents work by Nicholas Aloisio-Shearer, Rainer Ciar, Emma Harbridge, Merhdad Mehraeen, Yanti Peng, Audrey Pfister, Emma Pham, Emma Varker, Tanushri Saha, Donnalyn Xu, and Sophie Xiao Yue Zhou. Open World is a love letter to the virtual worlds that have shaped us, whether through online communities and sharing platforms, or cultural nostalgia and its accompanying fields of image production. The works in Open World encourage us to think beyond the teleology of linear gameplay, where the player is guided along a set path; open world games unfold with the player, shifting the focus from singular goals and objectives to exploration and intuition.But beyond sparkly Tumblr-kitsch and sexy avatars, Open World also speaks to the necessity of collaborative worlding in the analogue—of dreaming and creating liveable futures. Afterall, world is also a verb.

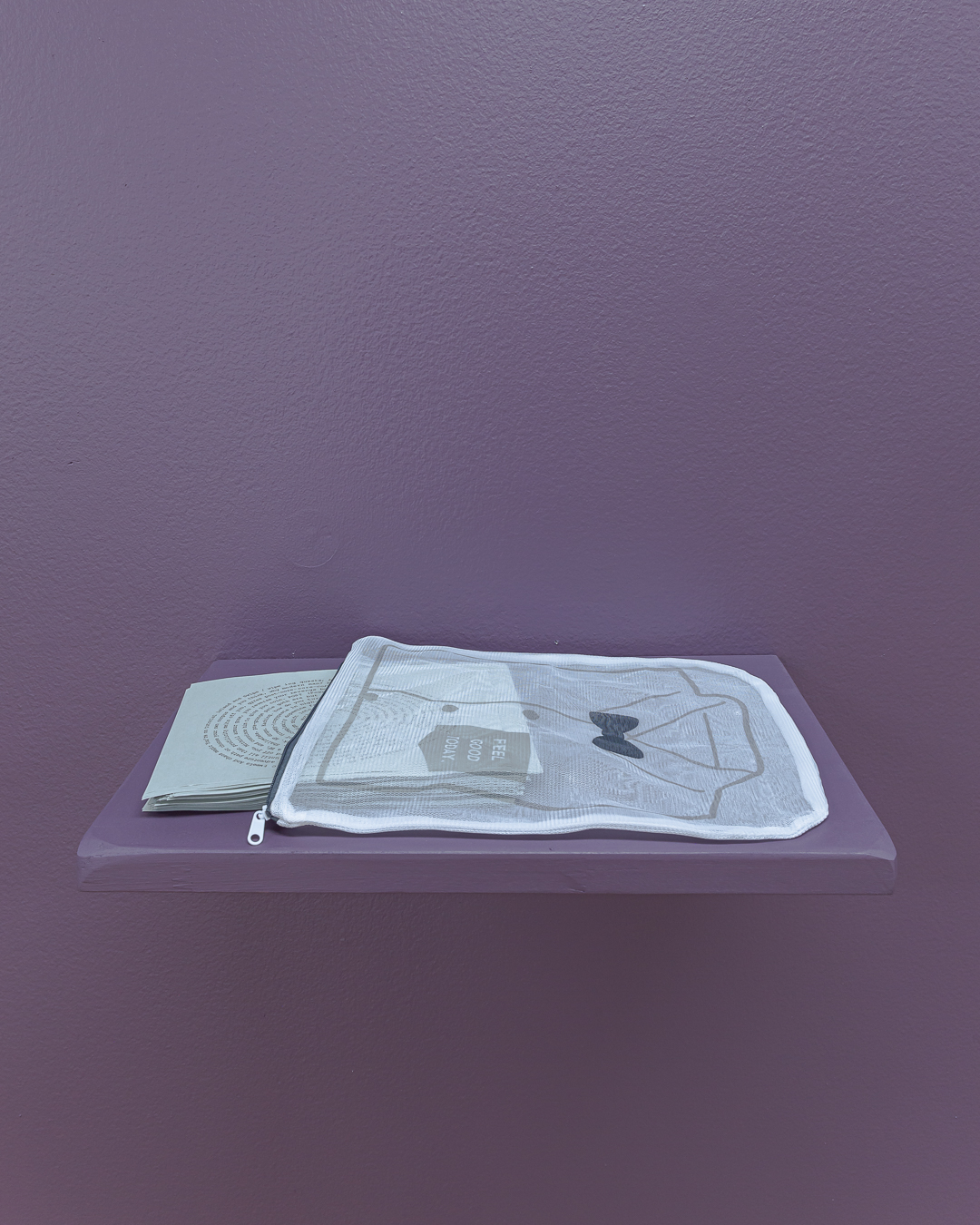

Inside the gallery, I gravitate towards a mesh laundry bag containing Audrey Pfister’s poetic post-post-post -femminie-urge-grindset rebirth (2023). In Open World’s companion text, Pfister describes their childhood addiction to playing RuneScape, and the crushing devastation of waking one morning to find their coins, armour, and inventory items stolen. The solution was to remake their avatar “but hotter,” with “bright purple pigtail hair.” Like Pfister, I was addicted to RuneScape, comparing RS BFs with friends on MSN. Born on the wrong side of the ’90s for Myspace, RuneScape also marked my first foray into the libidinal zone of online chatrooms, a swirling vortex of desire that coalesced around the erotics of the cyber-fantasy avatar.

As a child, the ability to transform the self by simply clicking an icon evokes the logic of magic; like casting a spell, the gamer’s body calls up computer-language, a chorus of 0s and 1s that make things happen. The synaptic flashes running between play, touch, and fantasy kindled an erogenous fixation, a sense that stroking language would make my world shinier, maybe sexier. I wonder if this early expression of haptic autonomy is what Pfister means by “madness thinking”—that sense buckles under the pressure of the endless-self, forever re-born and re-made.

Of course, we are already cyborgs, technology our second skin. Handheld computers collect our biometric data, while tech-prostheses expand our sensory worlds, blurring the once-clear boundaries that demarcated the analogue from the digital. In Emma Varker’s Basilisk (2022), the artist is translated into digital space using a combination of photogrammetry and 3D modelling. At first, the light from O’Connell Street darkens the screen so that it becomes a mirror. Varker’s AI-limbs slowly come into focus, moving as if locked in a deep-space vacuum. Without material objects to dance around or bump into, the artist’s spatial relation changes; touch is redundant. Basilisk—installed beside Varker’s durational video Two Hour Smile (2022)—highlights the ways in which environments affect embodiment, specifically how phenomenological experience shifts within the digital. Watching the artist’s eerie movements, I’m reminded of a talk I attended recently, where the speaker made an obvious, but salient point: The digital might be named after our digits (i.e., our fingers), but the digital doesn’t need keyboards or mousepads. Rendered digital, the body can only twiddle its thumbs.

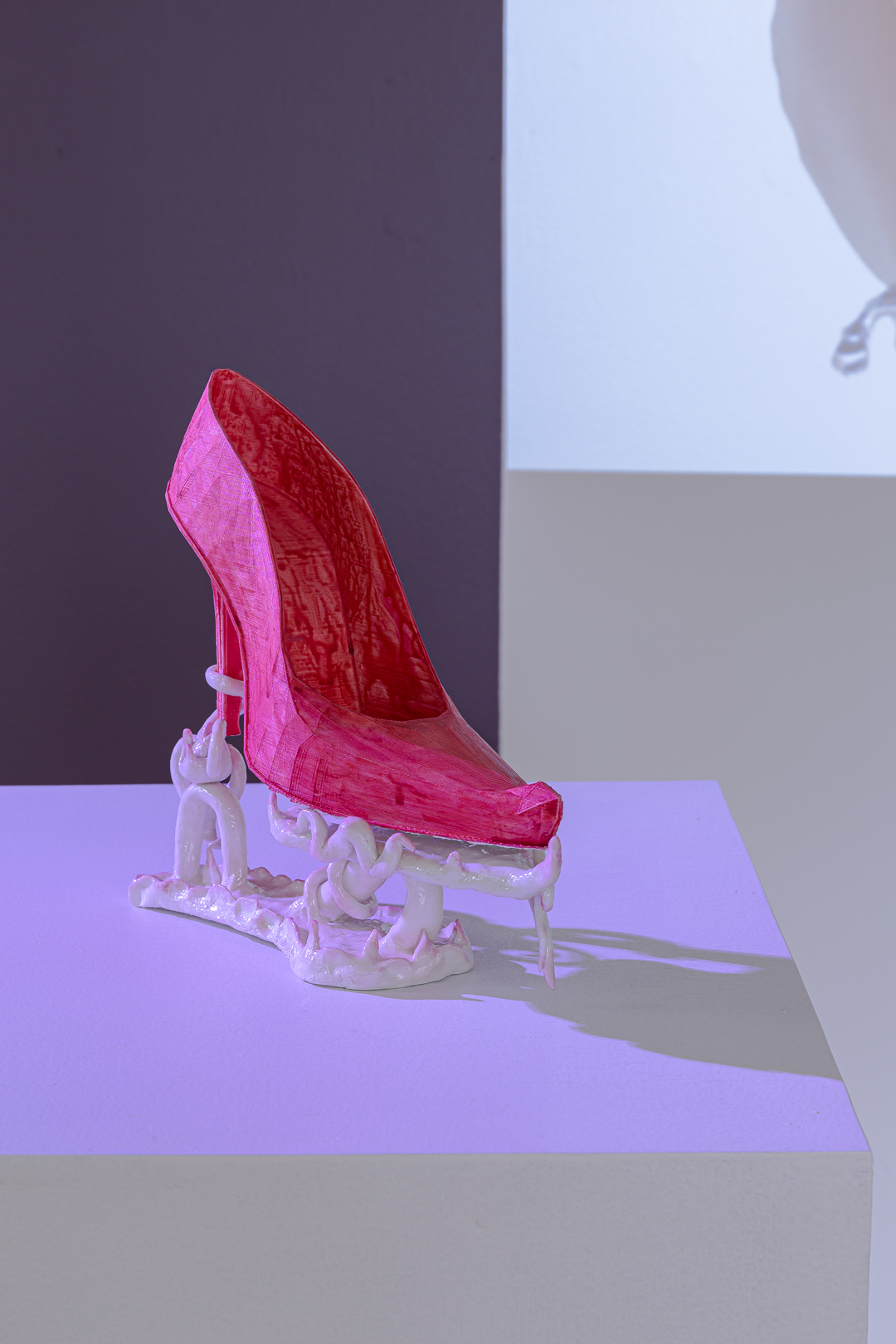

On the adjacent wall, Yanti Peng’s three works Everywhere I look, all I see is the Shoe (2023), 𓂇 (2023), and Love at First Shoe (2023), are also inspired by fantasy RPG games. Comprised of a video, a website, and a pink stiletto balanced on shiny white whorls, Peng’s work explores both the ways in which the virtual self affects the real self, and how commodity fetishism manifests in online space. Peng, as the titles of the works suggest, is fixated on a virtual shoe, which she would save up for by playing hundreds of mini-games within the game. Peng’s hot pink shoe reveals that even games selling themselves as fantasy utopias are contingent on cycles of and trade profit. Players buy—sometimes with real money—in-game items or “skins” to enhance the gaming experience; many of these items are purely aesthetic and serve no other function within the game. Post RuneScape, the sexiest avatars are experts in accumulation.

While Peng’s fantasy game would appear to have an exchange economy (i.e., items are purchased with real or virtual money), many in-game items materialise in cyber-space as always-already, self-referential objects. Divorced from any labour relation, they are imbued with a false intrinsic value: In cyberspace, commodity fetishism is a high-heel shoe. Peng’s overwhelming desire for the new pink shoe all the other avatars are wearing reveals the grip of capitalist modes of production on the cyber-dream avatar. However, by recontextualising the commodity as a material object, Peng’s 3D-printed shoe reanimates the in-game accessory with labour’s ghost.

In the language of feminist new materialisms, worlding refers to a particular blending of the material and the semiotic in a way that elides the divisions between subject, object, and environment. In Staying with the Trouble (2016), the multispecies theorist Donna Haraway has also written that “natures, cultures, subjects, and objects do not pre-exist their inter-twined worldings, but are always co-materialising in a storied poiesis.” This is a fun, but pretty complicated way to say that our worlds are ever-unfurling, flickering into life with every utterance and playful encounter. Unlike world building, often associated with gaming and fantasy novels, worlding’s subject emerges at the same instant as its object. There is no caesura between worlder and world, much like the coexistent universe depicted in Emma Pham’s Guardian Mother Spirit of My Computer (2023). Pulsing on the monitor in organic purples, greens, and blues, Pham’s animated tapestry is alive with ancestral spirits and pixels. In its symmetry and gentle repetitions, the tapestry presents a vibrant ecosystem of nonhierarchic images, worlding together.

However, Open World reminds me that traditional world building is also essential to the production of convincing narratives, virtual or otherwise. “Narrative” is a slippery word that belongs to fiction, mathematics, law, psychology, politics, and ideology; it is how we structure our lives and give shape to our worlds. In Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009), Mark Fisher writes that there is a “widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” In other words, late capitalism’s ideological “grand narrative” would have us believe that capitalism is the only narrative. But, as the artists in Open World know, a narrative is only as good as its side quests.

A narrative is a mesh laundry bag full of pixels, glitches, virtual lovers, and friends: an unruly pluralism that eats the totalising logic of late capitalism from the inside. In capitalism’s singular narrative, we are all, even if we refuse to admit it, the goblin in Nicholas Aloisio-Shearer’s woven Campo Dei Mazzamureddo (2023): “outcast wretches” residing on the incomprehensible frontier of economic precarity. Transcending this frontier—in order to call forth our magical goblin powers—means creating counter-narratives and alternate worlds, whether through political organising, fighting orcs, hacking the mainframe, D&D campaigns, or maybe falling in love. I delete, then rewrite, “Marx would have been a gamer.”

Before I leave the gallery, I try to take a photo of Emma Harbridge’s Surrender ur Weapon & Rest ur Heart (2022–23), but find that it is impossible to capture the sand, chains, origami stars, soap holder, notes, stickers, or golden durian from a single angle. The sculpture refuses the closure of totality; it remains open.

Toyah is a writer and PhD candidate living on Gadigal land. Her latest writing can be found in Runway Journal, Cordite, and Minarets.