No Easy Answers, Build Your Home, What Remains, Reko Rennie OA_RR

Ella Howells

Mum’s the word on the streets of Albury. It’s quiet, but there’s a hum around the Murray Art Museum Albury (MAMA), which was renamed as such during its 2015 redevelopment, joining a growing collection of maternally-monikered art museums. Originally built as the city’s Town Hall in the Victorian era “wedding cake rococo” style, the bride then underwent a facelift to match her fellow yummy-mummies MoMA and MUMA. The result? Glass prisms, white walls and double-height atriums that entice a renewed influx of urbanite acolytes.

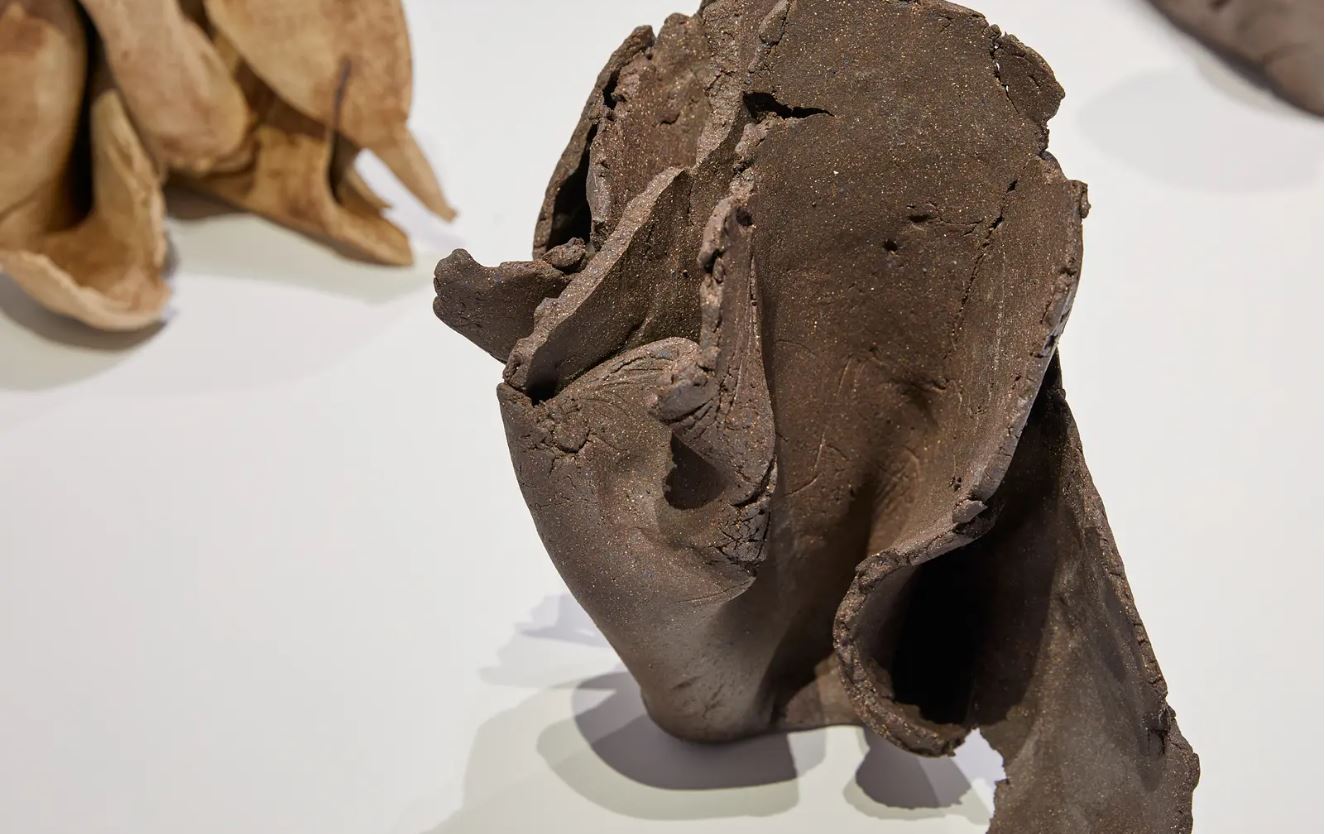

Consider me enticed. Freshly alighted from a freshly discounted V/Line journey from Southern Cross station (a return trip now costs $7.20), the exhibition that I’m greeted with on the ground floor is What Remains. It centres on six recently acquired works by First Nations artists, made in response to the changing conditions of Country and the subsequent temporalities of erosion and death. Each artist included takes this on with specificity to their homelands, yet the show feels grounded, literally: it revolves around Remain (2015), a series of ceramic works by Nicole Foreshew that are sculpted and glazed using the surrounding Wiradjuri land’s clay and pigments. Their forms appear heavy, emanating a centrifugal force that holds the surrounding works from the permanent collection rapt in vigil. These wall works expand the photographic focus that MAMA’s collection has retained since the inception of their acquisitive National Photography Prize in 1983.

Gunditjmara and Djabwurrung artist Hayley Millar Baker’s photo collage Untitled (The circumstances are that a whale had come on shore) (2015) alters the vocabulary of trust I tend to default to when deciphering black-and-white photographic images. A beached whale appears stark against a seascape, and after several minutes I realise that its placement is the result of a precise cutting process. Millar Baker recalls an event on Gunditjmara land where the Kilcarer Gundidj clan sought to glean a beached whale for meat, but colonisers counterclaimed the whale then massacred all but two of the group. The horizon line is sharp, so is the grief. Elsewhere, in Cornelia Parker’s The Collected Death of Images – aka Inhaled Images (the lost particles) (1996), grief appears hazy and hard to see through; an immersive Rorschach test. It’s a framed plate of rippled silver silt, collected whilst developing representational silver-gelatin images. After their lifespan, the particles illustrate loss through their detritic state, having mineralised into the aerial topography of a dust storm.

Underpants made from polished aluminium by Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens beckon us. Warrior Woman VIII and Warrior Woman XVII (2017) are pendant-encrusted chastity belt-like assemblages that expose the dual bind of protection and pain. Against the armour, soft strings of leather hold hearts at their ends. The binding knots proverbially untie during a moment of cathartic liberation in Dickens’s accompanying poem:

Big-girl underwear

Big-girl knickers

Tough and ready

Until the time allows

Then the cheeks will shake

run, dance, fart and sing

As the nakedness is unleashed

On the darkest of nights

Glowing under moons of glory

The poem positions Dickens’s knickers as metal monuments resigned to stillness after their muses have cast them off to freely move. In the atrium foyer, as part of the group exhibition No Easy Answers, the monument itself begins to move. Philadelphia-based artist Wilmer Wilson IV places monuments back in the hands of the masses with his installation of a billboard-sized banner that reads “TIL BRONZE FLOWS THROUGH THE STREETS.” Below, puddles of melted bronze splatter on concrete slabs, memorialising blood spilled at the hands of oppressive figures immortalised in bronze statues. Whilst this installation was initially exhibited on real outdoor billboards viewable from American “sidewalks,” Wilson suggested reconstructing the street-based component as Australian “footpath” segments for an indoor gallery audience, so a masterful member of MAMA’s installation team recalled his past as a concrete path layer to brush the borders of each block using a recognisable suburban technique.

Past the footpath and up the stairs, I’m met with a curatorial obstacle. No Easy Answers. I have no easy questions, because the premise of this group show promises “haziness,” “complexity,” and “contemporary challenges.” The curatorial strategy is open plan, which preemptively deflects critique. The gallery, with its inner partitions removed, is also open plan: standout works such as Tracey Moffatt’s Laudanum (1998), a series of psychosexual photogravures depicting a lesbian tryst between a colonial wife and her servant, appear alongside playful post-internet works that accelerate in their own lane but confuse the overall tone. Ella Barclay’s Dense Bodies and Unknown Systems (2021) visualises the innards of data farms through a three-channel video work that projects swimming bodies into rectangular troughs of swirling vapour. The campy RGB colour profile and wires that emerge at jaunty angles produce a mad-scientist effect that doesn’t take itself too seriously. Drinking from these troughs would be refreshing.

On the other end of the serious scale is Vitche Boul Ra’s CRIB: Neverstorm (2023). Ra (named after the sun god) is a self-described Transhumanist Folk-Theurgist who uses the pronoun “It.” MAMA Director Michael Moran recounts Ra’s ceremonial performance of marrying Itself in order to activate the installation, and I’m reminded of NBA player Dennis Rodman, who married himself in 1996 in a custom gown and Kevyn Aucoin makeup to become the “all-purpose person.” With the adaptive tech we have in 2023, is it possible (or necessary) for an all-purpose person to become a post-human “It”? Once Ra flew back to America, It’s performing body was de-ritualised, replaced by a revolving g-string clad cardboard cutout illuminated by desk lamps. Photoshoot fans blow a lace-trimmed veil, leading the eye up to a music video of It’s balaclava-clad face mounted on the ceiling. Cultural philosopher Byung Chul Han offers that rituals and ceremonies are genuinely human acts, and art that has been de-ritualised becomes a signifier of atomised narcissism that can only be healed through re-enchantment. Ra’s theurgic objectification traverses that line.

Ra’s music echoes throughout the space. I find myself interrupted by the transhumanist future whilst trying to contemplate humanist history through Christopher Hanrahan’s suite of fifteen paintings titled Folk Politics. This term refers to 1970s grassroots collectivism, yet the paintings are crafted by his hand alone, their utilitarian elements deactivated. Folk politics are earnestly represented in the adjoining room devoted to local artists who all work out of studios they built themselves, where works like Glenda Helen Mackay’s Quilts (2016) (which are modernist grids of upcycled pressed tin and hessian) are given the white-cube treatment. I remember my Mum’s grandfather who lived near Albury, assembling scraps from his workshop into small wooden trains and trucks. I think my mum still has her blue-painted ute. Functional artworks made for others demonstrate folk politics.

Now we enter the maroon cube, where the presentation of Reko Rennie’s three-channel video work OA_RR (2016–17) takes place on an appropriately cinematic scale. The walls’ burnished colour refracts the warm tones of the video throughout the space, enveloping the viewer in huge trifold screens. The bonnet of a golden Rolls Royce Corniche, covered in camouflage graffiti that Rennie honed painting trains during his adolescence, stretches out towards the Spirit of Ecstasy ornament greeting the road ahead.

The dusk settles in and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds are playing when the Rolls glides into a bush-lined bowl of scorched earth. Wealthy pastoralists like those who occupied Rennie’s grandmother’s land to milk the labour of the Stolen Generations and colonial migrant workers drove cars like this. But perhaps not quite like this … the speed picks up. Recalling Rennie’s teenage joyrides in Melbourne’s westside, the tyres start dancing, carving circles. Dust rises and the headlights glow through the reddish clouds. The scale of the screens amplifies the land art component of the work; the omniscient views of the circlework (doughies) evoke Kamilaroi painting techniques as well as the bird’s eye camerawork of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). In control of the careening car, Rennie locates joy within risk. The foregrounding of edgework and circlework in OA_RR (2016–17) confronts any generalised romanticisation of rural Indigeneity, highlighting the complicated relationships city-based Indigenous artists may have with place and Country.

On the train back home, the sun is setting and time stretches back onto the city clock. After walking the Yindyamarra Sculpture Trail along the banks of the Murray with the guidance of my friend’s mum Janet, I think about how MAMA draws vital attention to threads that knit the Wiradjuri region’s concurrent histories into generational complexities, resolved and unresolved. When inviting artists from beyond the region, national or international, there’s prescience of how friction in the works’ relationships with one another allows for deeper engagement. I mean, upon entrance, we’re invited to contemplate death. I’m grateful for this. I think about my great-grandfather again. When he passed away, I was four, so naturally I asked my mum if he would have managed to snap a photo of the afterlife to drop down to me. She explained that he wouldn’t have been able to bring a camera in his pocket. Next time I go to Albury, I’ll try to go with my Mum.

Ella Howells is a writer, artist and arts worker on unceded Wurundjeri land.