Nici Cumpston, Barkandji people, Old Mutawintji Gorge I-VII, from the series mirrimpilyi, happy and contented, 2023. Adelaide, Kaurna Country. Pigment inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper, hand coloured with PanPastel, crayon and pencil. (I-II) (VI-VII) 44 x 120 cm (each); (III-V) 120 x 44 cm (each). Raymond Zada, Barkandji/Barkindji/Malyangapa people, nets, 2023 (detail). Broken Hill, Wilyakali Country; Adelaide, Kaurna Country; Melbourne, Wurundjeri Country, spiny-headed sedge (Cyperus gymnocaulos), 50 x 300 cm (each) (variable). Installation view of Bunjil Place Gallery, 2024. Courtesy the artists and Michael Reid Gallery. Photo: Christian Capurro

ngaratya (together, us group, all in it together)

Nikita Vanderbyl

ngaratya (together, us group, all in it together) is a touring exhibition. It began its journey at Bunjil Place—Narre Warren on Boon Wurrung/Bunurong Country in 2023—but I am viewing it on Barkandji/Barkindji Country in far western New South Wales. Curated by sisters Nici and Zena Cumpston, the show features their work with four artists connected through kinship and Barkindji heritage. Adrianne Semmens and Raymond Zada are blood relatives of the curators, while David Doyle and Kent Morris are collaborators with the artists, also sharing Barkindji heritage.

The show begins with a welcome space, which establishes many of the key themes explored by the six artists. At the center is a knee-height table with photobooks, newspapers, and a biscuit tin of family photographs. The content of the newspaper reflects the significance of Country as a participant or co-creator in the project, specifically the significance of the Baaka-Darling River, or Baaka, as it’s known in these parts. The health of the river system remains subject to the policies and controls of government organisations somehow intending to balance the needs of agribusiness, downstream irrigators, and the environment, among others. Zena Cumpston’s latest publication Plants can be picked up too, foreshadowing the focus of her artworks. The photobooks tell the story of the exhibition’s development from the perspectives of the creators who have spent time on Barkindji Country (also spelled Barkandji or Paarkantji). Together they visited significant cultural sites and met with Elders during several trips in 2022. These are family albums, an important backstory to the exhibition, but also a kind of family history in six parts. It’s the viewer’s job to work out the connections and spot the familiar faces.

Installation view of Welcome Space—ngarayta (together, us group, all in it together), Bunjil Place Gallery, 2024. Photo: Christian Capurro

Later I return to this space, and this is exactly what is happening. Three white-haired aunties are gathered around the tin, sorting photographs according to family connection and discussing the lives of the artists, as though gathered around the kitchen table. While this is exactly the intention of the welcome space, I can’t help but feel it has extra resonance here, in Broken Hill. We’re on neighbouring Wilyakali Country in New South Wales’s far west, and five of the six artists have returned for the exhibition, with only David Doyle living nearby. Family connections are maintained across vast distances, so returning to their homelands has extra meaning for these artists.

Acquainting myself with the artists and their connections to each other is an important part of the protocol of entering ngaratya (together, us group, all in it together). Though the welcome space is given less real estate in this gallery than at Narre Warren, it is situated with the other artworks surrounding it: a way to ensure the visitor spends time here and is prepared for the journey that follows. Like the exhibition as a whole, it’s an invitation to experience belonging.

To be considered a local in Broken Hill you need more than just to be born here; you need to belong to the “A group.” The term describes mine workers from before the Second World War, with “B group” denoting those from away, the reserve laborers. The terms have stuck. Belonging is a contentious topic among locals, who have dug for themselves an identity dependent on the excavation of Wilyakali land. Each time I visit I feel I am witnessing a new dimension of this violent past. This time I learned from residents just how much the earth shakes during daily mining blasts. Being an outsider is felt keenly by visitors to Broken Hill. Against this backdrop, it is hard not to speculate about the significance of a group exhibition by First Nations artists explicitly about belonging. There’s a wealth of local First Nations talent surrounding Broken Hill, but it’s not often seen in the city gallery; this exhibition indicates a positive change.

Zena Cumpston, Barkandji people, ngarta-kiira (to return to Country) #1-#10, 2023, Melbourne, Wurundjeri Country. Linocut collage and kopi on Fabriano paper, (1-4) (7-10) 76 x 56 cm (each); (5-6) 56 x 76 cm (each). Installation view of Bunjil Place Gallery, 2024. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Christian Capurro

Recalibrating how we, and in particular non-Indigenous people, see Country and kin are at the heart of this exhibition. Each artist approaches the brief with a different medium. Zena Cumpston invites the viewer to think about First Nations foods through intricate linocuts and woven bush banana, or karkala in Barkindji language. ngarta-kiira (to return to Country #1-#10 (2023) depicts murnong, nardoo, kangaroo grass, kumbungi, sedge, and karkalla, alongside grinding stones, yabbies, and muscle shells, a catalogue of the bounty from Country. A large reproduction of a Frederic Bonney photograph from 1879, renamed Abundance—Jacob, Mary and Doughboy in 2023, shows who preserved this knowledge and how their culinary tools were used. The photograph is from a dark period on Barkindji Country, but it is repurposed here, I think, to challenge the viewer to see past narrow deficit discourses of cultural decline. Presented in larger-than-life scale with a printed handout identifying each of the tools and resources, this photograph foregrounds First Nations’s knowledge, rather than salvage ethnography, and, like the exhibition as a whole, epistemologically turns the tables.

Zena Cumpston’s artwork draws upon history in an intertextual way. Her detailed linocuts can be situated within a lineage of Barkindji artists using this medium. I’m thinking in particular of Uncle Badger Bates, whose work brings attention to the suffering of the Baaka and whose powerful words can be read in the newspapers in the welcome space, or on the exhibition’s website. One linocut reads: “There’s not enough left (for you) Aboriginal food it’s a white thing,” referencing not only Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman, and Gurang Gurang artist Richard Bell’s Bell’s Theorem, or “Aboriginal Art—It’s a White Thing” (2003), but the threats to First Nations’s intellectual and cultural property posed by the bush foods industry. Without stronger laws, bush foods are commercialised by non-Indigenous businesses with no interest in recognising intellectual property or giving back to the communities whose knowledge they have profited from.

Knowledge from the earth is embodied by Adrianne Semmens when she dances on Country. In her performance work, captured in the video kuntyiri, shadow, reflection (2023), Semmens uses dance to share knowledge and express the love and longing that returning to Country brings. I can see parallels between the flow of water and knowledge in Semmens’s movements, and particularly when a cotton yarn traces its course across her skin, the red sand, or the warm rocks. Three baskets of this woven cotton, dyed with rust, charcoal, eucalyptus, quandong, and bottlebrush, are situated next to the three-channel video. Titled Holding I-III (2023), they are incredibly liquid on film but so still on the wall. I wasn’t aware of the title as I looked closely at their small shapes, but imagined myself cupping them in my hands. Seemingly incomplete, a weaver might pick them up and continue the task.

Adrianne Semmens, Barkandji people, kuntyiri, shadow, reflection, 2023 (still). Broken Hill, Wilyakali Country, Kinchega National Park, Barkandji/Barkindji Country and Adelaide, Kaurna Country. Three channel video, stereo sound, 7 minutes 43 seconds. Composer: Amy Flannery. Co-director: Johanis Lyons-Reid. Courtesy the artist.

Weaving recurs both metaphorically and literally in ngaratya (together, us group, all in it together). Collectively the artists made a fishing net from spiny-headed sedge; it’s positioned above carved tools and cast bronze creatures in the assemblage by Barkindji/Malyangapa carver David Doyle. Karkala (bush banana), woven from spiny-headed sedge and coated in kopi clay, hang from the ceiling nearby, part of Zena Cumpston’s artwork. Doyle also includes karkala on his table, alongside lifelike yabbies making their escape across coolamons, bowls, emu eggs, boomerangs, and spears carved from kamuru (River Red Gum). Doyle’s artwork references the abundance in Zena’s work, and through his carving and weaving practice highlights the significance of the River Red Gum as a vital part of Barkindji culture. Kamuru not only provide the wood for canoes, but the means to carry water, shelter under their branches, fuel for a fire; their hollows helped birth thousands of Barkindji people and stand proud over the bodies of the old people who have passed on to the dreamtime. The River Red Gum literally means life and death in Barkindji culture.

David Doyle, Barkindji/Malyangapa people, kamuru – river red gum, 2022–23 (detail).

Nici Cumpston, Zena Cumpston, David Doyle, Kent Morris, Adrianne Semmens, Raymond Zada, Barkandji/Barkindji/Malyangapa people, nets, 2023 (detail). Installation view of Bunjil Place Gallery, 2024. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Christian Capurro

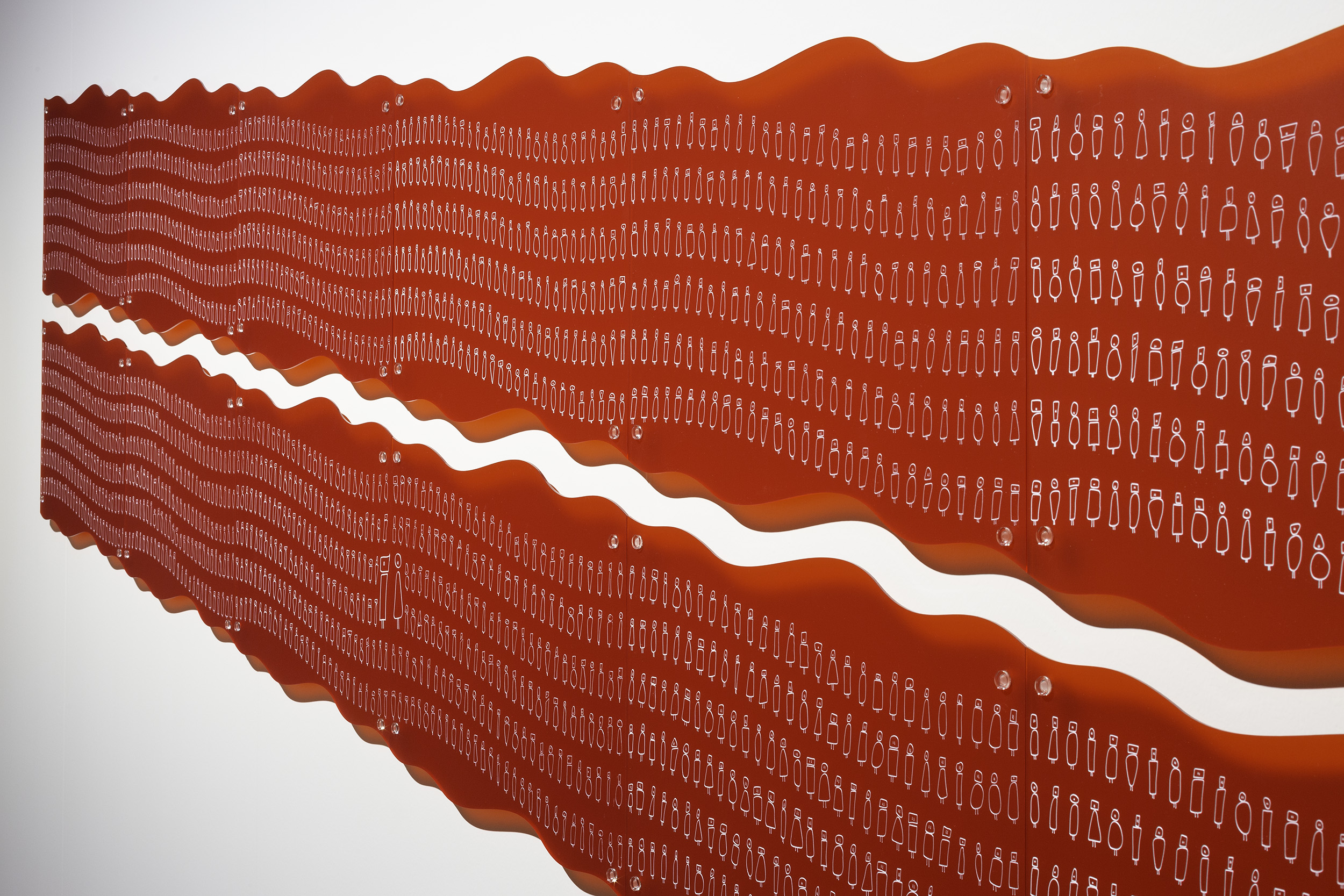

Raymond Zada, Barkandji people, Bloodline, 2023 (detail), Adelaide, Kaurna Country. 12 etched acrylic panels, enamel paint, irregular, overall height 208.9 cm, width 317.4 cm. Installation view of Bunjil Place Gallery, 2024. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Christian Capurro

Raymond Zada’s etched acrylic panels, titled Bloodline (2023), take the theme of ancestral inheritance and make it explicit. On the wavy red panel are etched two thousand and forty-six figures, a hand-drawn homage to every ancestor who contributed to Zada’s DNA over the past ten generations. Zada’s work is conceptually rich, while visually it’s deceptively simple. Like family photographs, or your own unfinished family tree, Bloodlines will occupy your thoughts. It reminds me of Bigambul and Kamilaroi artist Archie Moore’s kith and kin (2024) at the Venice Biennale. Both Zada and Moore locate us temporally as much as physically through the scale and responsibility of inheritance.

Nici Cumpston’s relationship to Country is strengthened through acts of remembering. Her photographs of Old Mutawintji Gorge have been hand coloured from memory with PanPastels, crayons and pencils, an act that feels important to the process of seeing anew and receiving knowledge about Country. Using a large-format camera in black and white, Cumpston prints the images on watercolour paper before applying colour slowly by hand. Each leaf, rock, and body of water has been recalled after her travels. Mutawintji National Park is a cultural site 130 kilometres northeast of Broken Hill and renowned for rock art. It is also where ceremonies have been held by the artists’s ancestors for millennia. The sensitivity with which Cumpston applies the colours of Barkindji Country renders these images familiar and welcoming; they look like regular photographs, but their meticulous creation process gives them a hyperreal quality.

Kent Morris is also interested in encouraging us to see Country in a new way. His photographs of the karta-kartaka (Pink Cockatoo), a threatened species, are transformed from an ornithological interest into mesmerising kaleidoscopes illustrating how animals, humans, plants, sea, land, and sky are interconnected and interdependent. They allude to journeys of awakening to new understandings. A single perspective becomes an immersive network of patterns suggesting literally many ways of seeing. Here, using photographs from Mutawintji National Park, the landscape is transformed into symmetrical patterns designed to capture the generations of knowledge and meaning-making in the place, exemplified by the karta-kartaka’s important role in Barkindji creation stories. The video work, Karta-kartaka (Pink Cockatoo) #7 (2023), shows mutability in action as new shapes and patterns are revealed from within each other. Our minds can change as knowledge is gifted to us, but we must work to unpack its meaning.

Kent Morris, Barkindji people, karta-kartaka (pink cockatoo) #2, 2023. Mutawintji, Traditional Owners Country and Melbourne, Yalukit Willam Country. Inkjet print on Moab Somerset Museum Rag paper, 100 x 150 cm. Courtesy the artist and Vivien Anderson Gallery.

This exhibition is an invitation to unlearn our inherited racism through experiencing the generosity of the artists and their ways of seeing Country. Seeing in a new way, understanding the importance and interconnections of Country—it is hard to overstate—is a significant decolonial undertaking. The artists and curators chose a specific culturally grounded way of working to achieve this goal and were supported by Bunjil Place and NETS Victoria to determine the shape and direction of the project. It’s a real privilege to witness the results, and I hope many audiences get to do so as the exhibition tours.

Nikita Vanderbyl is a historian of First Nations art and Australian colonisation. She lives on Barkindji Country in western NSW.