Negotiating Borders

Soo-Min Shim

The Korean War (1950–53) is often referred to as the “Forgotten War”. Forgotten because its media coverage was censored and its memory overshadowed by both World War II and the Vietnam War. And yet, over seventeen thousand Australians served in it, and Australia became the second nation, behind the United States, to commit personnel from all three armed services. In doing so, Australia played a key role in a war that resulted in the death of more than three million Korean civilians and the construction and maintenance of one of the world’s most heavily militarised borders.

Australia is, however, good at forgetting its wars. It actively forgets the Frontier Wars, its military involvement in the Cold War, its occupation of Papua New Guinea by Australian forces until 1975 and Australia’s invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2003. The list goes on.

Forgetting warrants artistic interventions of active remembrance. Refusing to confront a military past serves to justify ongoing militarisation. Negotiating Borders at the Korean Cultural Centre Australia in Sydney provides just such a critical form of active remembrance. This traveling exhibition was initiated by curator Sunjung Kim in 2011 as part of the Real DMZ Project. The Real DMZ Project focuses on the “demilitarised zone” (the DMZ), a strip of land 248 kilometres long and four kilometres wide that stretches along the Korean Peninsula. Established after the Korean War in 1953, the DMZ separates North and South Korea. The Real DMZ Project explores this border as a product and symbol of the Korean Peninsula’s ongoing political and cultural tensions (including its record sixty-nine-year ceasefire) through curatorial and artistic research. The current staging of the project in Australia provides space for a much-needed critical perspective on the Korean War’s legacy both here, and beyond our borders.

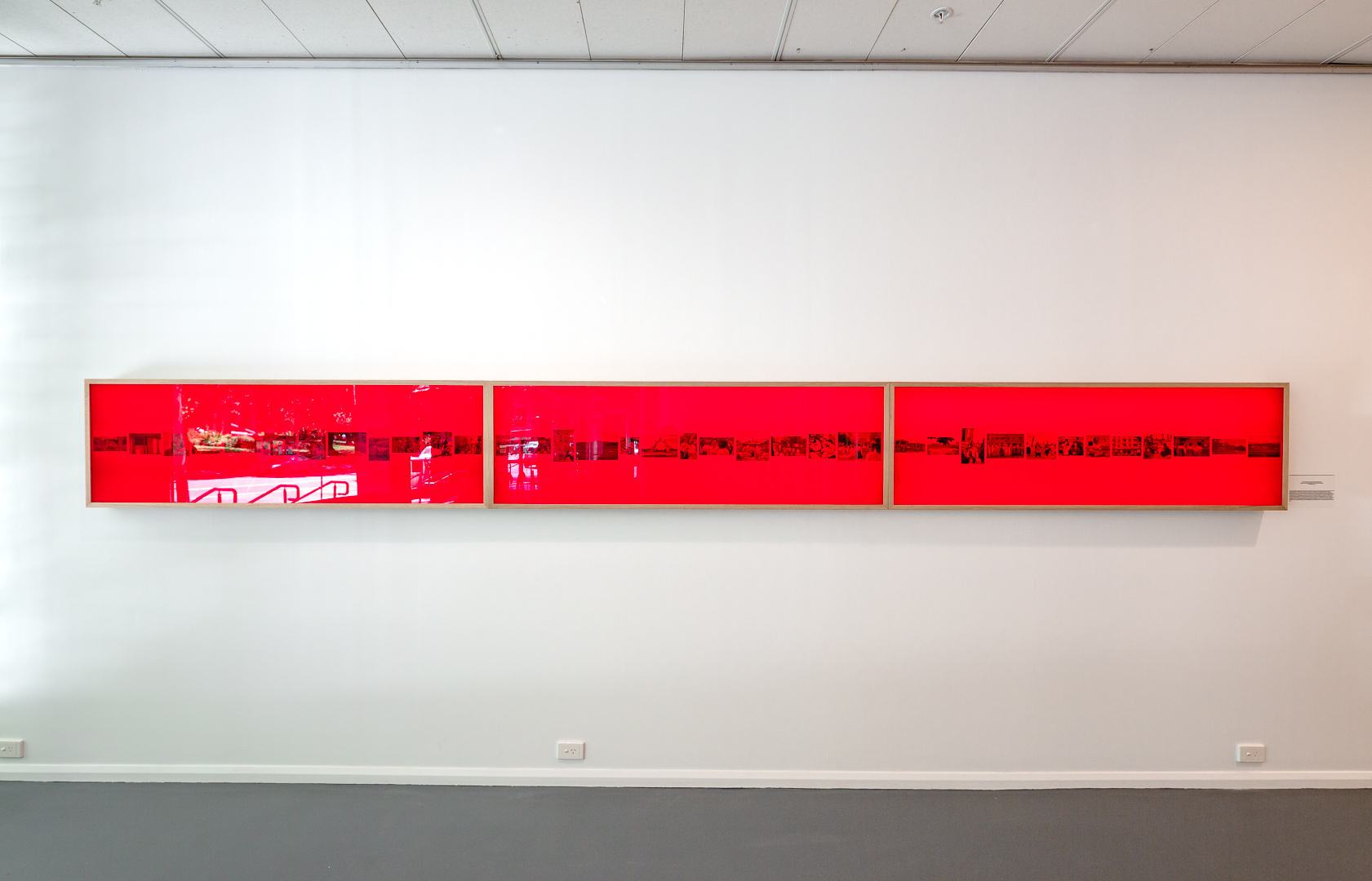

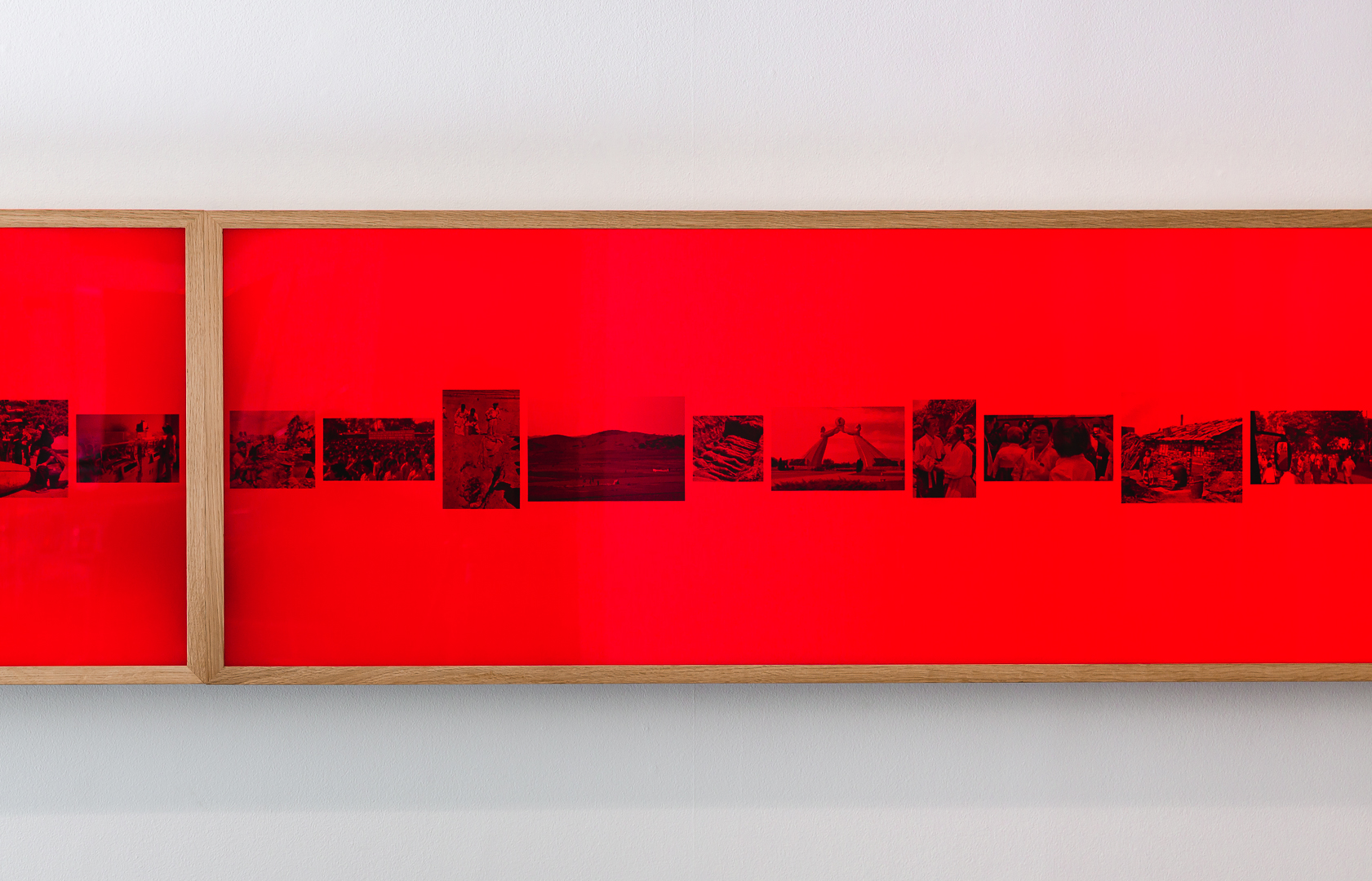

The first work to greet the visitor into the Centre’s exhibition space, Jane Jin Kaisen’s installation Apertures/ Specters/ Rifts (2016), immediately frames the legacy of the war with an archive of thirty-six photographs on red light-boxes. The photographs are derived from two different sources. The first is From North Korea: Impressions from the End of the World (1952), a book by Danish journalist and activist Kate Fleron after her 1951 visit to North Korea as a representative of the Women’s International Democratic Federation. The other is Kaisen’s archive of photographs from her own visit to North Korea in 2015 as part of the international advocacy group Women Cross DMZ. The glaring red light from the three wood-and-glass frames makes it difficult to look at the images directly, and I found myself straining my eyes to fully decipher each image. This aesthetic effect suggests that “true” images of North Korea are not easily accessed, and neither should they be easily consumable. Whilst the display ostensibly resembles a timeline, reading from left to right, the chronology flips from 1951 to 2015, subverting any historical impulse to narrativise in linear form. Instead, we are presented with a mix of images of stone monuments, groups of women, pastoral scenes and village landscapes. It is difficult to tell which images are from 1952 or 2015 as the past blends into the present.

Kaisen’s fragmentary approach obscures as much as it reveals about the legacy of the Korean war, and refuses to sensationalise it. She thus departs from the tabloids’ preoccupation with “uncovering” the secrecy of North Korea, or providing a glimpse behind the world’s “last iron curtain”. Negotiating Borders also bears comparison with other recent exhibitions of North Korean art, including in Australia, which have been underpinned by a Western neoliberal logic of visibility. In such displays, “exposure” and being “exhibited” often bleeds into both exploitation and commodification. In 2009, for example, curator Nick Bonner brought North Korean art to the 6th Asia-Pacific Triennial. It was the first Australian exhibition of contemporary North Korean art and to my mind it was a sensationalist event. At the time the Federal Government was publicly decrying the North Korean government and its missiles and nuclear weapons programme. As a result, the Federal Government banned the North Korean artists from visiting Brisbane for the Triennial, and the 6^th^ APT made international news and major headlines. John McDonald’s review of the APT emphasised difference and mystery, declaring: “The inclusion of a specially commissioned group of works from North Korea is probably the most controversial part of this year’s APT … we are invited to glimpse the world through North Korean eyes”. The 6^th^ APT seemed to rely on the marketing and hype generated by the “never-before-seen” North Korean art, touting itself as displaying “artists from countries never before included in APT … including North Korea, Turkey, Iran and the Mekong River region of South-East Asia”. Furthermore, the artworks displayed at the APT were from Mansudae Studio in Pyongyang, owned by the North Korean government. They were, in many ways, the stereotypical socialist realist paintings expected from North Korea. Reviews like McDonald’s point to their reception largely as propaganda, confirming a singular viewpoint of North Korea in which citizens are brainwashed and oppressed. The strength of Negotiating Borders lies in its inclusion of several artworks that display an active awareness of, and departure from, problematic expectations of colonial difference.

YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES’ video OUR DMZ (2021) is a new work commissioned especially for the Sydney exhibition (full work accessible here https://yhchang.com/OUR_DMZ.html), and could be read as a parody of the West’s paternalistic fascination for North Korea. In the video, the viewer is taken on a fictional two-hour bus ride from Seoul to the DMZ with “DMZ ECO-FRIENDLY WELL-BEING BUS TOURS”, led by a fictional tour guide called Sunny Kim. The video hyperbolises the absurdity of the tourism industry that has proliferated around North Korea. In an eerie, automated Australian-accented voice, Sunny Kim declares: “On this tour you’ll get a glimpse of the difference between freedom and democracy here in the South and the hellish dictatorship of the North. Today I am your guide to the outer ring of that hell”. The script continues to exaggerate the Western media’s stereotypes of divided Korea: “Only North Koreans don’t go to heaven. They get sent to secret camps outside of Pyongyang, where there’s barbed wire fences and nothing to eat. That’s a joke except it’s also the truth”. OUR DMZ provides a satirical critique of the capitalist monetisation of traumatic political events as Sunny Kim addresses the audience: “this is a special moment and although none of us may be special outside of this DMZ ECO-FRIENDLY WELL-BEING BUS TOUR bus, because this is a special moment we are de facto special people”. While the video is a highlight of the exhibition, the video was not given its own viewing platform, instead visitors were offered a QR code to scan with their phone (which I did when I got home).

In Negotiating Borders there were some works that slipped into a Western logic of paternalism towards North Koreans. Kyungah Ham, for example, presented two very bright hand-embroidered pieces — Needling Whisper, Needle Country / SMS Series in Camouflage / Are You Lonely Too? C01-01-02 and Big Smile C01-01-03 (2014-15). To create these works Ham secretly sent computer-generated digital diagrams to North Korean embroiderers via intermediaries in China, who then also smuggled the resulting works out. Regarding this border-crossing work, Ham writes that “bribe, tension, anxiety, censorship, ideology” are essential materials. With this in mind, I was left with the feeling that Ham’s work exacerbates the pre-existing perceptions of North Korea as the “hermit kingdom”, where systems and thoughts are operating in ways different from those on the “outside”.

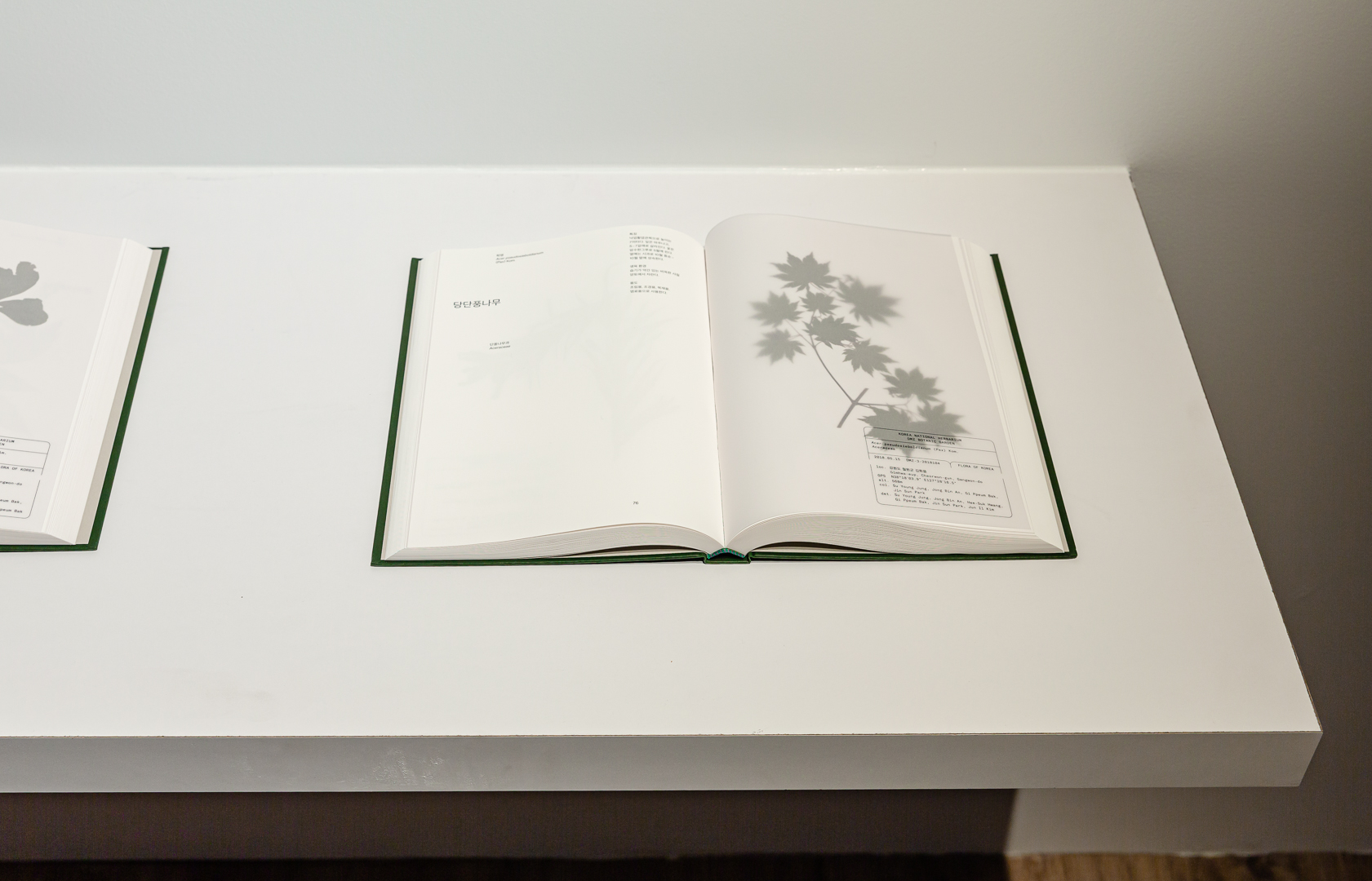

Jane Jin Kaisen’s video Sweeping the Forest Floor (2020) avoids paternalistic pity for North Koreans. Kaisen attaches a camera to a mine detector and, in a single-take shot, sweeps along the Landmines Civilian Control line, a region located five to twenty kilometres from the DMZ to the South. It is estimated that between 1.1 and 1.2 million landmines have been planted in South Korea by South Korean military, US military and North Korean forces. Kaisen does not favour any one political side but rather, by embodying an ecological viewpoint, highlights the multi-layered, nuanced, complexity of North and South Korean relations. We are positioned alongside the peace activists, sifting through foliage, identifying and clearing away mines that continue to destroy the environment. Similarly, Kyung Jin Zoh and Hye Ryeong Cho’s installation DMZ Botanic Garden (2019), placed next to Kaisen’s video, delicately displays the landscape of the DMZ and its unique ecology. The Korea National Arboretum includes three hundred species of DMZ plant life and DMZ Botanic Garden presents eighty-four of them for publication. They have been dried and classified, and presented in a book and on slides on an installed television screen. 235 taxa of rare plants, including fifty-one critical endangered species, have been identified in the DMZ. The human impact of war is delicately alluded to through the ecological damage it has wrought, presenting a broader view in which both North and South Korea would need to collaborate to preserve and restore the flora and fauna of the peninsula.

Ultimately, it was the works that used obfuscation and occlusion as a strategy that continue to haunt the viewer. Refusing didacticism or sensationalism, these works turn towards the poetic, perhaps embodying a more honest viewpoint by recognising that we may only have half the picture. It is through the oblique that a more generous image of the separation between North and South Korea emerges. In December 2021 Australia and South Korea signed a one billion dollar defence deal, the largest defence contract ever struck between Australia and an Asian nation. While demilitarisation seems distant, exhibitions such as Negotiating Borders serve as acts of active remembrance of the potential destruction of warfare.

Soo-Min Shim is an arts writer living on Gadigal land and is a PhD student at the Australian National University.