Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa: The Garden of Forking Paths

Rex Butler

It's almost impossible to imagine the influence four small volumes of less than 60,000 words each by the great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges exerted on Western culture throughout the latter part of the 20th century. Compiled from a selection of short stories and essays originally written in Spanish in the 1930s and '40s, Fictions and Labyrinthes first appeared in French in 1951 and 1953 and then as Ficciones and Labyrinths in English in 1962.

The great post-War generation of French philosophers all adored and attempted to channel him. (There is a wonderful photograph of Derrida meeting his hero for the first time and looking like a nervous schoolboy.) The whole group of American meta-fictionalists—Robert Coover, John Barth, Donald Barthelme—were all absolutely inspired by him. The Conceptualists drop his name incessantly in their writings. (The recent Robert Smithson show at MUMA featured Smithson's own heavily underlined copy of Labyrinthes) The post-modernist Sherrie Levine in her attempt to prove the author was dead kept on reprinting an excerpt from Borges' 'Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote' as an artist statement. (If anything, it proved the opposite.)

His influence has perhaps faded slightly in the new century, but in the early days of the internet one still could read any number of essays connecting it to Borges' Library of Babel, and novels like William Gibson's The Difference Engine and Mark Danielewski's House of Leaves and films like Christopher Nolan's Memento and Charlie Kaufman's The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind would be inconceivable without him.

Now Borges is called up to underwrite an exhibition at Buxton Contemporary, The Garden of Forking of Paths, pairing the Adelaide-born but now Melbourne-based Mira Gojak and the Tokyo-born but now Berlin-based Takehito Koganezawa. It's actually a pretty witty idea, if one is prepared to overlook the potential “Asianism”.

The original story of the same title—probably Borges' definitive literary expression of his defining notion of the “labyrinth”—features a Chinese spy Yu Tsu, who wishes to let his side know the location of the new British artillery facility at Albert in France during World War I, but is pursued by the relentless Irish agent Richard Madden. Realising time is running out and having no way to communicate his discovery, he decides to kill the famous sinologist Stephen Albert, knowing the news will get into the newspaper and they will figure out his intended message. But when Yu meets Albert, Albert seems to expect him and soon is telling him of his grandfather Ts'ui Pen, who once wanted to write a book in the shape of a labyrinth that would encompass “several futures” without choosing between them. Nevertheless, although bewitched by what Albert is saying, as Yu sees Madden approaching outside he shoots him, hoping his message will be passed on. The story concludes with the admission that the assault on Albert, which was already planned before its namesake's murder, was delayed because of rain and that the same paper that carried news of Albert's death also carried a story of the attack upon the British munitions facility.

The story is first of all a dramatisation of Zeno's long-standing paradox of motion, which Borges was always fascinated by, which states that we can never get from A to B because the space between them is infinitely divisible, but only—and here is the catch—because we're already able to count back from B. And this leads to Borges' brilliant reconceptualisation of the labyrinth not as the banal splitting into different paths between which we have to choose, but that through which events turn out exactly the way they were always going to. There is an immutable fate awaiting all of us, but this is only to be arrived at through the infinite number of free choices we make at every moment of our lives.

So it was kind of witty that the didactic at the entrance to the show could boil all of this down to “the affinities, differences and overlapping and divergent impulses that link and separate Gojak's and Koganezawa's work”. It'd be like the curators, Melissa Keys of Buxton and Shihoko Iida of the forthcoming Aichi Triennale, playing the role of Ts'ui's labyrinthine book predicting and putting together the Australian (not Irish) Gojak and the Japanese (not Chinese) Koganezawa. It's a clever conceit, mocking both the traditional curator's claim that it all comes down to their “eye” discerning the secret affinities between the artists they combine and the more recent opt-out that the curator is not trying to determine the various works they present and not making any particular connections between them.

Of course, on the other hand, drawing on one of Borges' greatest and most influential short stories to underwrite a two-person art exhibition is like getting Isaac Newton to referee a playground collision between schoolkids. In a way, what it can boil down to is on some things Gojak and Koganezawa are close and on others they are far away. But this is perhaps to say that this is a show more about the relationship between the two artists than either one of them as such. Or even that holding them up next to one another like this allows us to see certain things about their work that would not otherwise be visible, but that an infinite number of other combinations would do the same thing.

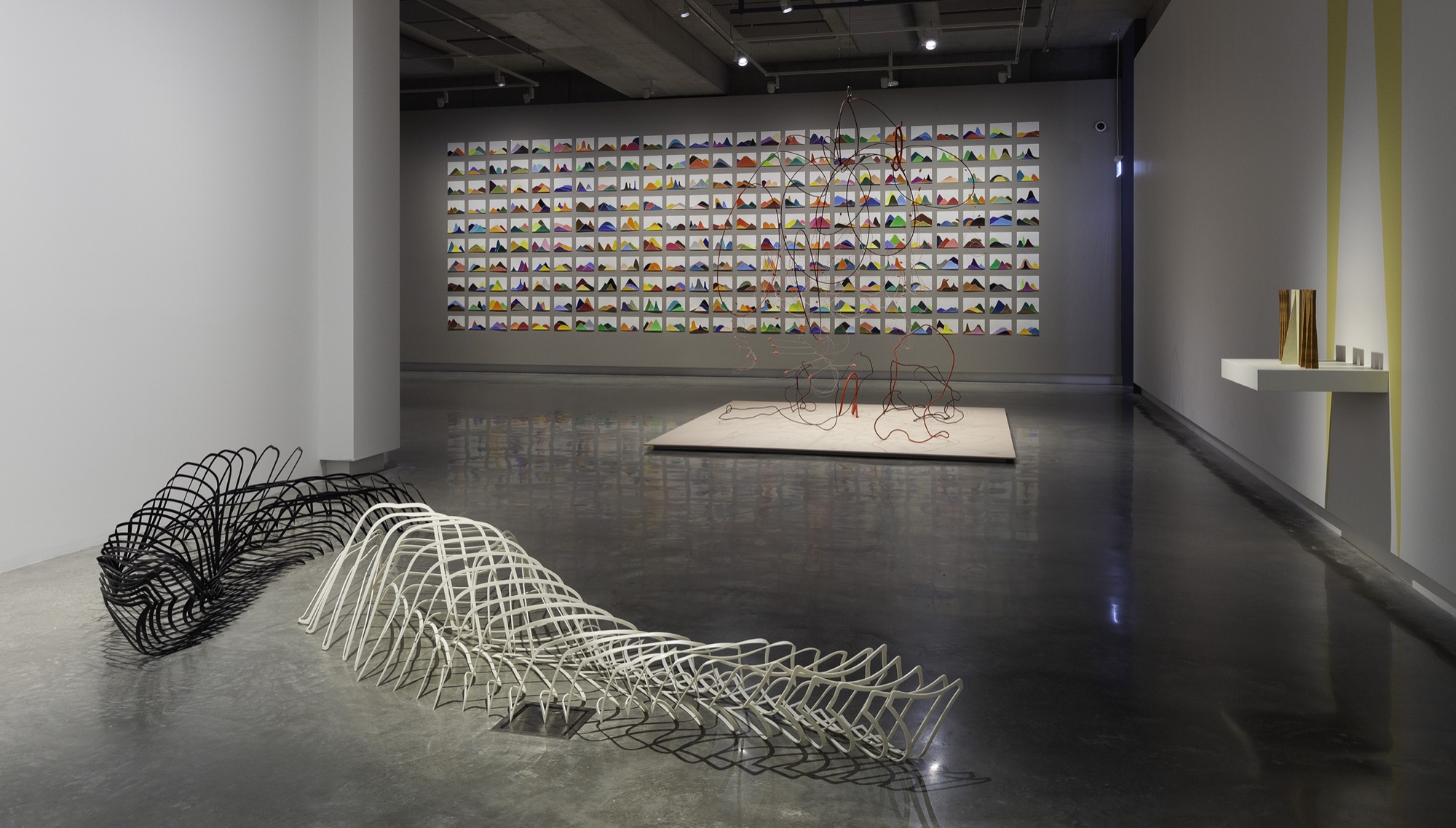

There is undoubtedly a “lightness” about both artists' work, which is first of all a form of delicacy or sparingness. It often appears made with little effort or as a kind of distraction. (We might think here of Gojak's Something Has To Go, 2006, featuring drawings made as physical therapy, or Koganezawa's Drawing in Pursuit, 2018, which seems similarly regressive in style.) Or it has a kind of first-draft quality about it, which is sometimes literally the case. (Again, we might think of Gojak's wire sculpture, From the Outside to the Outside, 2009, which has an undoubted sketch-like feel, or Koganezawa's vitrines of working drawings upstairs from 1996 to 2017.) There is a kind of unmaking instead of a making, or at least these become something of the same thing. (Here we might think of Gojak's disassembled bedroom cupboard and mirror, Consolation, 2005, or Koganezawa's video Paint It Black and Erase, 2010, which features him repeatedly covering a surface with pen that is each time wiped clean.)

But there is also a literal lightness to the works, a fascination with air or the atmosphere, in what we might even call a form of 21st-century Impressionism. Most notable here is Gojak's Cutting through the Vast Plain of Day (2018), made by tearing aerial photographs to form both clouds and holes in the sky. (Go back to Brunelleschi's original optical diagram to see this equivalence being made.) This is paired in the exhibition space with Gojak's sculpture Mountain, 2018, and Koganezawa's video RGBY, 2004. But perhaps a more inventive—dare we say “labyrinthine”?—curatorial gesture would have been to match Cutting through with Koganezawa's video Dust (2010), currently up on the first floor, in which magnified dust particles sparkle and flash as they drift through an invisible atmosphere, or even his Fly Drawing (2010), currently behind the front desk, which is a video of the path a fly traces on a white wall, eventually cutting out a small incision on the screen.

Then there are Gojak's Distant Measures (2016), Exhaled Weight (2017) and Places Stores (2017), Louise Weaveresque sculptures in which blue yarn is endlessly wrapped around bent wire frames, with the group of them, the didactic assures us, using up enough thread to reach the edge of the earth's atmosphere where “outer space” begins. Of course, seen in this light, the blue string can seem like a beautiful metaphor for what connects us to planet earth, while the wire frames operate like anchors rooting us in worldly concerns.

And this, we might suggest, is the last sense of “lightness” we might associate with the two bodies of work: that of their treatment of socio-political issues, the usual dead and intractable weight that drags down most contemporary art. Any artist today taking up the atmosphere for their subject has got to address the fact that we are living in the era of the anthropocene: the reality that the climate is now, at least in part, human-made. The icecaps are melting, small islands in the Pacific are submerged and the underlying cosmic order has been broken.

Kogenazawa's slow motion split video From Warm Mud (2018) of mud and water and oil and water respectively mixing and not mixing—which in its very difference is an unexpected echo of his two videos downstairs showing sped up coloured lines running out down the centre of a page like the median strip down the middle of a road—can't help but make us think of the impermanence of the world, but they're also just like close-ups of abstract paintings and a reminder that art will not entirely melt away. Gojak's sharply-focussed photographs of a bush stone-curlew's eye contracting in response to a change of light, Grey's Sun, 2018, can't help but make us think of nature as a kind of target, but they also capture a magnificent Olympia-like stare back at the spectator for their lack of action.

There are some equally acutely observed curatorial decisions in Forking Paths. In the room featuring a series of Kogenazawa's animations, Setting the Butterfly Free (2018), made by allowing a felt pen to bleed through the paper of a notebook and then flicking through the pages, there is also his Mountains (2016), a shape-shifting frieze of coloured pencil drawings of Mt Takao, 40 kilometres east of Tokyo, and Gojak's Silence (2005), a long line of disassembled plastic chairs, stacked front to back one inside the other, reminiscent both of Muybridge's famous images of animal locomotion and a little more obscenely of the infamous human “centipede” formed by the sewing together of victims' bodies in the movie of that name.

Of course, after Banksy's iconoclastic gesture of shredding his spray-painted stencil of a girl holding a balloon after it was bought at auction, an endless number of magazine and newspaper articles debated whether he was sincere in this gesture, whether this was a true criticism of the art system or a hypocritical pseudo-radical sneer. But putting it the other way around, we might propose that all works of art today should come equipped with a shredder and if they don't measure up then the spectator can push the button.

But all of this sounds a lot like Borges' 'Garden of Forking Paths', which is precisely about the way Yu's murder, Ts'ui's labyrinth and Borges' short story each cancel themselves out. And this is ultimately the difference between great works of art and the rest: great works don't need anyone or anything to shred them, they do it themselves. Think Hannah Gadsby's hard on Picasso? Have a good look at Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and realise that one of the prostitutes so sexually objectified there is a self-portrait of the artist himself. His work is already about the things she accuses it of. He's already Hannah Gadsby, just as Hannah Gadsby in her own routine is already her own best (and funniest) critic.

Nearly all of the works in Garden of the Forking Paths feature a similar self-erasure or self-destruction. The only real question is: do they do it themselves or do they need someone to do it for them?

Rex teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.