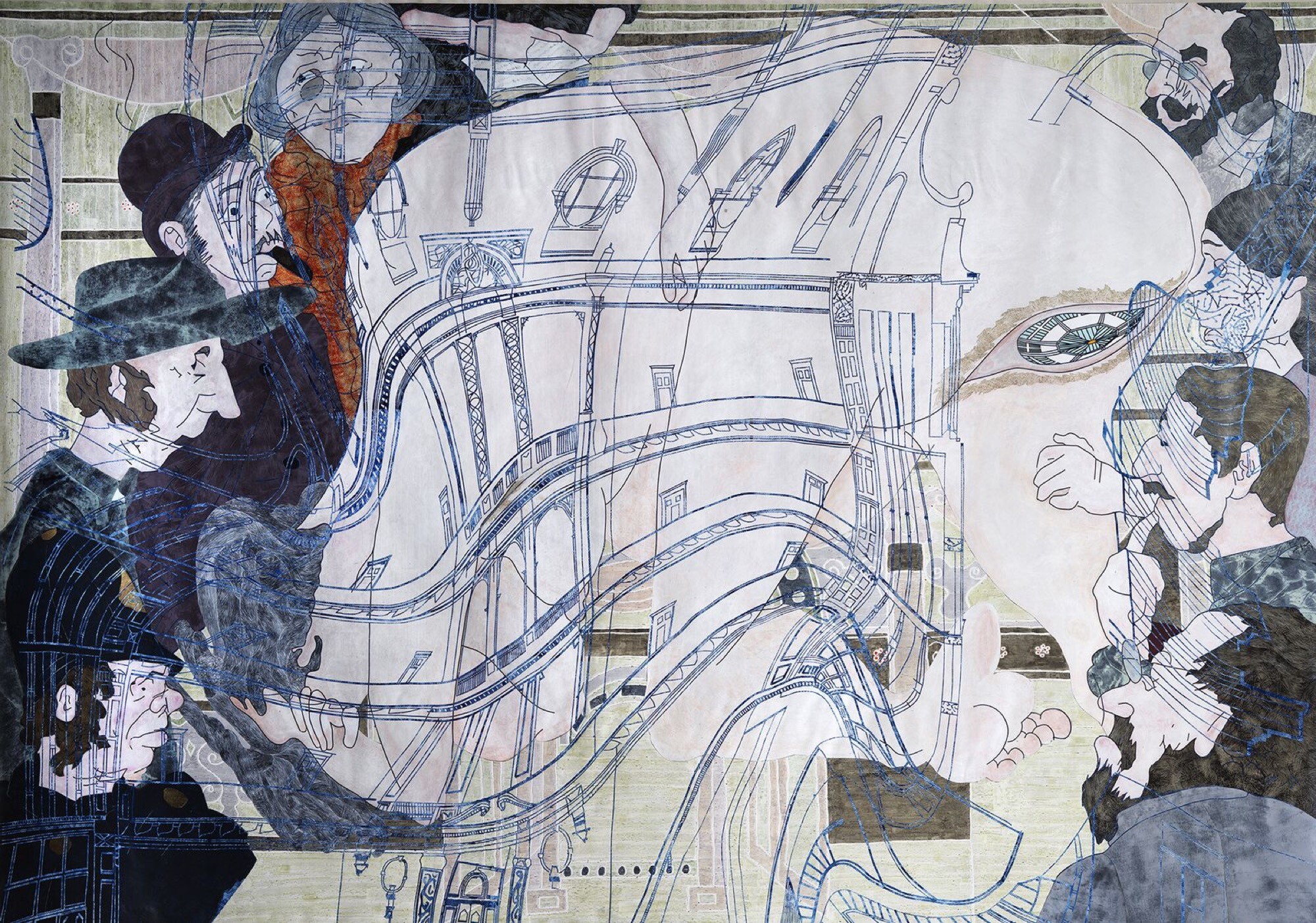

Michael Parekōwhai, Cosmo McMurtry, 2006, synthetic polymer paint on nylon fabric, fibreglass, fan, 734.3 x 506.4 x 739.1 cm (variable). Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria.

Michael Parekōwhai

Giles Fielke

“Fuck the clutch!” I still remember Helen Johnson yelling this out loud. This was years ago. The context was Vernon Ah Kee’s Dark + Disturbing (2013), a series of T-Shirts, including one emblazoned with the words “australia drive it like you stole it.” Last week, her painting The Birth of an Institution (2021–22) was invoked at a seminar addressing “convict aesthetics” in the Linkway Meeting Room at the University of Melbourne, which looks out and down across the city. In the painting, which was commissioned for and first exhibited during the National Gallery of Australia’s Know My Name project, a retinue of colonists look on while the glass dome of the State Library of Victoria crowns from a languid vagina at the arse-end of a distressed maternal body. Once arrived, baby institutions begin to demand their toys. The conventional modern toy, of course, was the motorcar. Today it’s the device. What if our institutions’ toys are public artworks?

Helen Johnson, Birth of an institution, 2021-2, recto, acrylic and pencil on unstretched canvas, 304 x 417.5 cm. MECCA Collection. Photo Andrew Curtis

Michael Parekōwhai is an artist and professor of Fine Art at the Elam School of Fine Arts at Auckland University. He is also currently at the centre of a Melbourne City Council fiasco that has recently hit the dailies. As The Mail headlines go, “Shocking photo shows everything that’s wrong with local government in Australia” feels somewhat run-of-the-mill, but it doesn’t necessarily bring to mind the image of a public artwork commission. Yet the image of the new sculpture, titled Tomorrow, comprised of an oversized kangaroo covered in fairy lights sitting on a chair, is a pretty great surprise for those willing to take the click bait. (To be clear, this is not a “photo” but an artificially rendered, “artist’s impression”—not Parekōwhai—of an artwork the reporters have only read about, and which has perhaps not yet been fabricated.) Closed council documents seem to have been leaked. Four extra works have been added to the original 2018 commission awarded to Parekōwhai, since delayed by Covid. In addition to Tomorrow, there is also Yesterday, Seal and Pleiades, Knowledge, and Intention). The commissions are now projected to cost twenty-two-million dollars and might be delivered by 2027. The claim from the council documents that this will be “the most transformational public art commission ever undertaken in Australasia” seems to transcend hyperbole. Heads are, reportedly, ready to roll. My own employer, the University of Melbourne, has also been implicated: some kind of alleged quid pro quo to do with approvals for its Fisherman’s Bend campus mean it will help to foot the bill. There’s an upcoming mayoral election (the outgoing Mayor has just been employed by the University; the favoured candidate is a senior executive there). It’s a complex tale. What I am interested in here is not how deep the rabbit hole really goes, but what the rabbit is made of. After all, if we’ve learned anything from modern public artwork commissions, it is that they must be inscrutable.

New Zealand artist Michael Parekōwhai in front of his giant rabbit sculpture Cosmo at Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Building in 2006. Photo: AAP

Sydney PR blow-in Prue MacSween has had the gall to weigh-in on Melbourne’s problem: “How can anyone believe that an 8-metre high kangaroo was ‘transformational’ public art. I mean it’s just astounding that anybody would find this inspiring or reflective or what Melbourne stands for.” In Parekōwhai’s defense, it seems he might have hit the nail on the head, albeit a fraction too hard here. The twenty-two-million dollars that these public commissions will reportedly cost is in reality the cost of keeping the grift going. These institutions exist to normalise theft, of (Aboriginal) land and labour (see University wage theft). They also require toys, and some might also be read through “convict aesthetics,” let alone the nightmare visions afforded the next generations already normalised to hyperviolence and hell-world dystopia easily viewable on their parents’ devices. In dog years, these institutions are now 2024 years old.

Nine News, “Artist Impression” of Parekowhai’s commissioned sculpture, Tomorrow. Forthcoming 2027.

It is not the first time that public artwork commissions have come into the remit of the public shame cauldron that is the advertorial news cycle, and coincidentally the locus of this current fracas, Dodds Street, faces the current location of Ron Robertson-Swan’s Vault (1980). At that time, the news decided we didn’t like it and the Victorian Government, led by Dick Hamer, had the entire Melbourne City Council sacked. Now on the grounds of the Wood Marsh-designed ACCA hulk, “Steel Henge” or “The Yellow Peril” (racism included) finds itself adjacent University of Melbourne’s Southbank Campus uplift project forty-five years after its unveiling at City Square on Swanston Street.

There is another logic here, about the amount of money public projects like this might generate. Hilariously, it has been argued that for every dollar spent on the Parekōwhai commissions, $4.20 will be earned via increased tourism to the city. Corporate consulting plays itself; autophagy is a victimless crime. What we are witnessing here is the logic of the city as a metropolitan centre that generates revenue because that’s what institutions do. In return they demand toys.

“Memo under Vault,” community photo at Das Boot, 2022, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. Courtesy Esther Stewart and Oscar Perry.

It feels as though the city is on the cusp of our very own Tilted Arc moment. In 1981, the late Richard Serra installed a giant COR-TEN steel divider at Foley Federal Plaza in New York, a work of public art that attracted defenders and detractors all the way to court. Rosalind Krauss, defending Serra’s work at a public hearing, argued that the Arc’s public service was to tell its viewers something about the nature of seeing—in particular, the way in which seeing is always purposive, guided towards a purpose or goal, like mapping a path across a public plaza. Many of today’s public artworks also offer a model of seeing—not a gaze directed outward, but rather one that throws us back our own image. Think of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate (2006), or Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994–2000), which sold in 2013 for more than eighty-five-million dollars. (A yellow version of the series was installed on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2008.) The vulvic imagery of Callum Morton’s Bull (2023), now on display outside the Australian Embassy in Washington D.C., wryly participates in this ocular-centrism of the public sculpture. But it also fits within the logic of the baby institution (here Australia in the US). Sadly, Morton was passed over for the Dodds Street commission.

In Australia, Parekōwhai is best known for his sculpture The English Channel (2015). Acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2016, it is currently installed in the entrance pavilion of the Gallery’s new building. The didactic describes an image of Cook who “seems to be reflecting on his legacy in the contemporary world. At the same time, his dazzling surface collects the reflection of everything around it—including the harbour past which Cook sailed in 1770 and the visitors in the room.” To say that the work deploys the finish fetish that characterised so much US sculpture in the twentieth century is an understatement. But to ignore this is the point. What is considerable is the way Cook’s image might be rehabilitated if he is remade by a Maori (Ngati Whakarongo) artist. Thomas Woolner’s sculpture of Cook, now often the target of decolonial actions, was unveiled in Hyde Park in 1879 to an audience that possibly included Joseph Conrad, who was in Sydney at the time. This was a decade before his work as a merchant sailor sent him to the Belgian Congo, and two decades before he would publish Heart of Darkness. The semantic ambiguity of the line “exterminate all the brutes,” written by the crazed Kurtz in a report to his European superiors in Conrad’s book, operates in a similar way to many contemporary art projects, which operate as both criticisms and celebrations of colonisation. Here the aesthetic principle is play, yet we can’t do this with these scaled monuments. They are for the institutions to play with, hence why the public might see them as a threat.

Michael Parekōwhai, The English Channel, 2015, stainless steel, 257.0 x 166.0 x 158.0 cm. Entrance Pavilion, Art Gallery of NSW

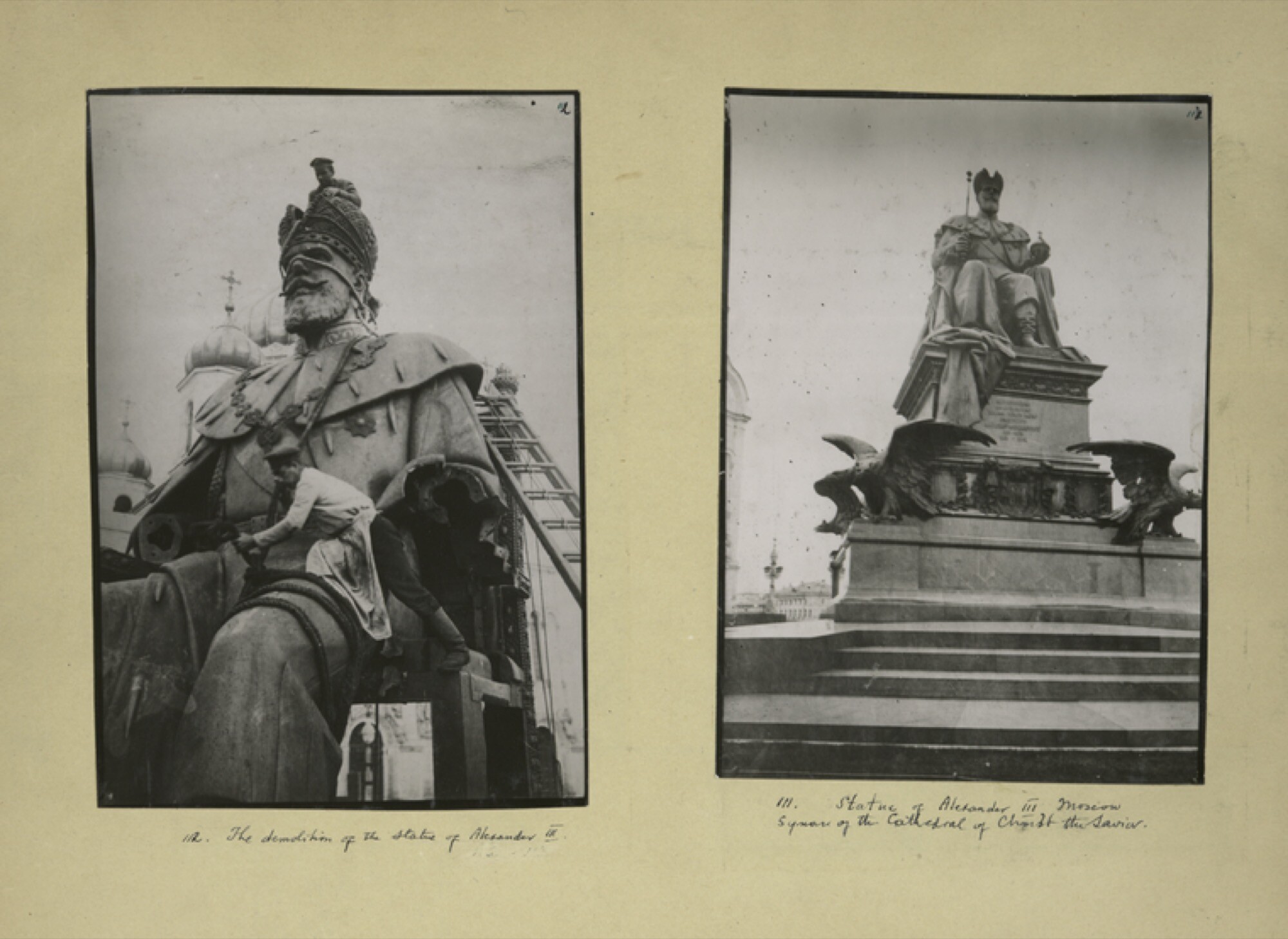

When the baffles finally come down from City Square, it feels right that Charles Summers’s statue of Burke and Wills (1865) should be returned there. They might even feel contemporary (currently they’re hiding in a shed in South Kensington, awaiting their return). This will also allow us to link the nineteenth to the twenty-first centuries. Because, if it is true that “twentieth-century sculpture has repeatedly taken forms that have been difficult for its contemporary viewers to assimilate into their received ideas about the proper task of the plastic arts,” as Rosalind Krauss claimed in the year before Vault was installed in Melbourne City Square, so far, the twenty-first century has been unable to free itself from the sense that no proper public task is preferable. Furthermore, this is because, just as Krauss mistakes the penultimate Romanov Tsar Alexander III for his son Nicholas II in the opening scene of Eisenstein’s October at the beginning of her book Passages in Modern Sculpture, there is a sense that our generation is born from the next. The Gates of Hell have been locked. We’re stuck inside. One day a film might re-enact the collective dismantling of Parekōwhai’s eight-meter Kangaroo on Dodds Street. Perhaps this commission was selected because it is the national symbol we also regularly eat. The sustenance here has diminishing returns.

Statue of Alexander III in Moscow; Demolition of the statue of Alexander III, 1923. Photo: New York Public Library

Bruce Pollard (1936–2024) passed away this week. I’ve only seen a single post commemorating his life, on Peter Tyndall’s Instagram account. Pinacotheca gallery opened at 1 Fitzroy Street, St Kilda in 1967 and exhibited important work by local and international artists, both there and in its Richmond galleries, for more than three decades. It is against Pollard’s project that this latest confection of a scandal about art and public life should be measured. Something like the Robert Rooney/Simon Klose (Collaboration) from 1972, where the cities’ iconic bluestone putchers were installed on the floor of the gallery, only to be thrown out onto the street again at the end of the show. There is something very odd happening with the state of the art of the state today. It is undeniable. A transitional moment, perhaps. A market correction. An eight-metre kangaroo. Laura Riding once claimed that writing correspondence was the closest one can get to anarchy in polite society. Consider this my letter to public art in Narrm and more broadly. When the world feels like a bundle of tongues looking for an arsehole, you gotta be the arsehole.

Robert Rooney, Bruce Pollard 2, 1979, 1979 (printed 2012) inkjet print on paper (sheet: 24.0 cm x 35.2 cm, image: 20.0 cm x 30.5 cm). Canberra: National Portrait Gallery.

Giles Fielke is an editor of Memo Review.