Installation view of Melbourne Out Loud: Life through the lens of Rennie Ellis, State Library of Victoria. Photo: Christian Capurro

Melbourne Out Loud: Life through the lens of Rennie Ellis

Digby Houghton

Neoclassical, pale-white Corinthian columns dominate the forecourt of the State Library of Victoria (SLV). I am here to attend Melbourne Out Loud, a retrospective of photography by Rennie Ellis. Instead, I am hypnotised by the grandeur of the building housing it. A statue of Supreme Court Judge and SLV co-founder Redmond Barry greets me as I ascend the steps from Swanston Street, flanked by the modern bronze figures of Joan of Arc and St George slaying the dragon. These reminders of Melbourne’s nineteenth-century haute bourgeoisie might seem at odds with the photography of Ellis, popularly known as a champion of the everyday. But the juxtaposition underscores the stakes of this exhibition: whose everyday appears in Australia’s visual history, and how might we see this history differently?

Born in the south-east suburb of Brighton in 1940, Ellis is known for his iconic images of Australian life, such as his black-and-white photos of 1970s subcultures (like the Melbourne Sharpies), his scenes of Australian beach life, and his documentation of the 1975 protests at Melbourne’s City Square following the Whitlam dismissal. Between 2010 and 2016 the SLV acquired more than half a million photographs by Ellis, including negatives that have resulted in twenty-five-thousand images becoming available online, and the production of two books: Decade: 1970 to 1980 (2013) and Decadent: 1980 to 2000 (2014) (both published by Hardie Grant Books in association with the SLV). The present exhibition—the first to draw from this collection—spans Ellis’s career from the 1970s, when he opened Brummels Gallery of Photography in Melbourne and published his photo-book Kings Cross, until his untimely death in 2003.

Installation view of Melbourne Out Loud: Life through the lens of Rennie Ellis, State Library of Victoria. Photo: Christian Capurro

The exhibition, curated by Angela Bailey, presents Ellis’s work primarily by way of a set of three digital slide sequences, each focusing on a different aspect of Ellis’s work. When entering the exhibition space from either of the exhibition’s two entrances one can see glass-tinted structures that serve as viewing booths for two of these slide sequences. These booths are composed of two walls that meet on a ninety-degree angle, with photographs projected on either side. Each of these booths is supplemented with a selection of framed photographs and ephemera. At the gallery’s Swanston Street entrance, the booth presents work focused on photo essays from Ellis’s unpublished proof-of-concept Decade book (before the 2013 publication), the Flinders Lane “Ragtrade” strip, and a selection of graffiti photographs, along with piles of Spirax notebooks and media passes on lanyards. At the Russell Street booth there’s a focus on Brummels, the commercial gallery that Ellis opened in Melbourne in 1972. Between the two booths is a large space with cushions and couches spread out for spectators to view a thirty-minute projection slide. This projection is accompanied by music chosen by the host of PBS show Boogie Beats Suite, Dj MzRizk.

Installation view of Melbourne Out Loud: Life through the lens of Rennie Ellis, State Library of Victoria. Photo: Christian Capurro

Melbourne Out Loud contrasts with the recent 2017 retrospective The Rennie Ellis Show at Box Hill, which was limited to photographs from the books Decade: 1970–1980 and Decadent: 1980–2000. Melbourne Out Loud offers a distinctly different glimpse into Ellis’s work, tapping into the SLV’s digital archives to offer a seemingly endless stream of images that stretches far beyond the bounds of the published photobooks. This recasting of Ellis’s work as an overflowing panoply of images is expertly articulated by the architecture and design, coordinated by Melbourne-based architects Baracco & Wright, who also designed the SLV’s 2023 exhibition (MIRROR: New views on photography). The two shows both have a distinct connection to Melbourne and Victoria (MIRROR focused on emerging and established Victorian storytellers), and both deployed the booth and slideshow format. As in the prior exhibition, Baracco & Wright’s design for Melbourne Out Loud frames photography in the digital era as a site of super-abundance: for every photograph one registers and focuses on in the booth there is a myriad of alternative images playing out on the booth’s other wall, and in the remainder of the gallery.

Such an approach is not entirely out of keeping with Ellis’s work, and jibes with the frivolity of Ellis’s character and the photographs’ subject matter. Ellis was the kind of militant documenter who—anticipating our present trigger-happy photo-taking era—would photograph anything and anyone. This approach brings with it both problems and possibilities.

Installation view of Melbourne Out Loud: Life through the lens of Rennie Ellis, State Library of Victoria. Photo: Christian Capurro

Ellis has been hitherto mostly understood as a champion of the everyday of mainstream Australian culture. He captured the beach, Melbourne Cup Day, the AFL grand final and concerts like Sunbury Music Festival in 1973 (the exhibition even includes a media pass to Crown Casino’s opening night on June 30, 1994). The significance of these events in Australia history, however, is often occluded by the exhibition’s emphasis on images over text. For example, among the few framed photographs that complement the slide presentations are three devoted to the Whitlam Dismissal protest of 1975. Whitlam Dismissal Protest, Melbourne (1976) is an extreme long shot showing teems of people flocking the city with banners reading “Patriotic Anti-Fascist Front – Stop CIA puppet Fraser”. Another photograph, Labour Party Rally (1975), captures protestors on the footsteps of the aforementioned columns of the SLV proclaiming “Gough’s turn for a full term” in painted banners. The exhibition’s decision to favour photographs over text here means that no textual information is given about the broader significance of Whitlam’s dismissal. Without such context, these photographs look like any other 1960s or 1970s activist uprisings that might be found anywhere in the world.

The 1970s was indeed a period of great cultural flourishing in Australia. Even before Whitlam was elected in 1972, Don Chipp, the Liberal Minister for Customs and Excise introduced the R-rating for movies in 1970, allowing previously censored films to be screened in their entirety to adult audiences. Chipp’s role is important because a letter dated from 31 July 1970 is encased in one of the cabinets at the Swanston Street entrances. Ellis praises Chipp, stating “just a line to let you know that my staff and I support your moves towards updating Australia’s archaic censorship system.” The Whitlam government picked up where the Liberal Gorton government left off with regards to censorship by reducing the banned list of literature to zero by 1973. This historical development played an important role in Ellis’s career: in 1973, Ellis was a stills photographer for Tim Burstall’s 1973 sexploitation film Alvin Purple. This seedier—but perhaps also more interesting—aspect of Ellis’s oeuvre remains absent from the exhibition.

The exhibition’s strategy of visual overload, and image over text, however, also allows for the emergence of often obscured histories. The exhibition is curated by Angela Bailey, a Brisbane-turned-Melbourne curator and artist who, through various projects and including her current role as vice-president of the Australian Queer Archives, has contributed significantly to the historical preservation and recuperation of queer history in Australia. In the 1980s she was an active member in the resistance against Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s conservative government and its homophobic policies. When she moved to Melbourne in the 1990s, she became visual arts director for the Midsumma festival. The sounds of Filipino / Wiradjuri singer Mo’Ju reverberate over the PR system: “change has to come; change has to come.” These lyrics are repeated over rotating images of the gay liberation movement—established by the yellow block font writing in the bottom left corner of the projected wall: “gay pride week and march 1973.” Mo’Ju’s lyrics wash over me as the projected images and the vocals become closely intertwined. In the light of such works and Bailey’s own prior work, the exhibition establishes a subtle link to artists like Nan Goldin and William Yang, who also deployed the slideshow format to frame histories of queer activism and communality.

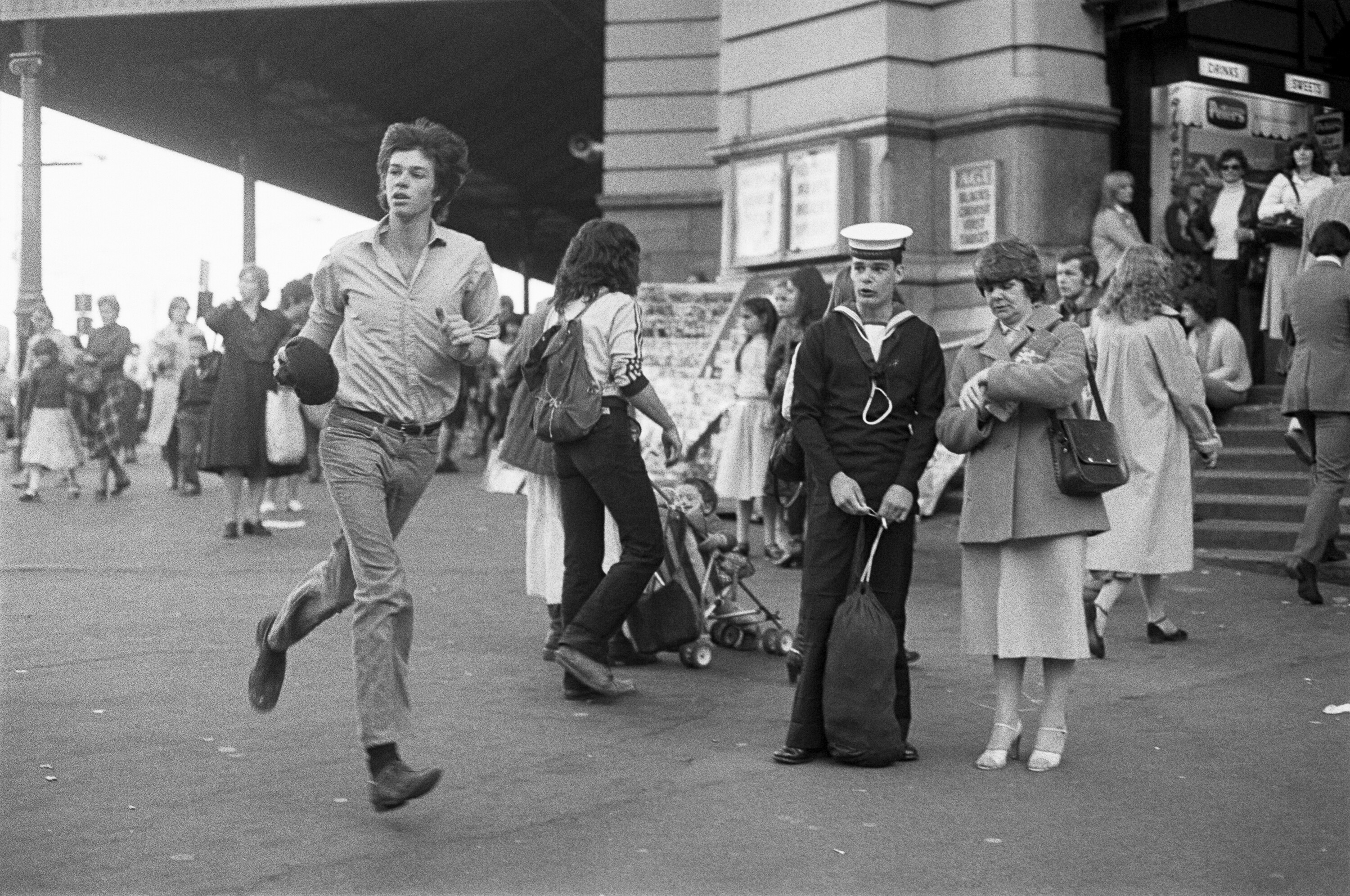

Rennie Ellis, In a hurry, Flinders Street Station, 1980, photograph. Courtesy of State Library of Victoria.

The exhibition also gives light to other marginalised histories. Flashing up briefly in the slide shows are images of the Italian communities of Melbourne’s inner city, Timorese youth, and Cambodian Buddhist Ceremonies (1985). While Ellis’s photographs certainly gave iconic form to conventional masculine white Australia, the exhibition brings to light his imaging of less mainstream facets of Australian society. Timorese Disco Party (1998) features eight B-boys with denim jeans and oversized polos posing with peace signs and Fosters tinnies in their hands with looks of elation across their faces. This photograph precedes the East Timorese crisis of 1999, but it captures a moment of unrestrained joy.

Ellis captured Australia in all its abundance and bareness: from pop-stars to rock stars and political slogans to mundane representations of the everyday. Bailey’s curation serves as a testament to Ellis’s achievement, portraying Australia as it was throughout the defining decades of the 1970s through to the early 2000s. The overabundance of images allows the iconic photographs by Ellis to shine light on the less familiar ones. If one looks closely enough, an alternative Australia can be found here.

Digby Houghton is a film critic, filmmaker, programmer, and screenwriter from Melbourne. He is interested in the intersection between history and film and is the 2024 AFI Research Collection’s fellow where he is developing a screenplay based on Melbourne film culture from the 1970s and 1980s.