Melbourne Now

Chelsea Hopper

“It seems significant that we don’t want things to be quiet ever, anymore,” David Foster Wallace remarked in a 2003 interview. While he was referring to “almost any public space in America…piped with music,” Melbourne Now can be added to the list. This sprawling multi-level bonanza of art, design, jewellery, architecture, and fashion filtered for us in an interactive QR-coded map, beckons our short attention spans to follow the sound everywhere.

Furniture music loudly fills the ground-floor foyer, presumably a commissioned sound work. I ask who the artist is. “No one. It’s just music,” says the gallery attendant. Things don’t get easier in the exhibition. Try viewing Kate Daw’s video Reverse Anthem (2021) without overhearing Damiano Bertoli’s Beware the Badly Belted Boy (2019) and the rattling bass from Rel Pham’s installation TEMPLE playing across the room. Even stopping to watch Scotty So’s lip-syncing video work plonked between two whirring ascending escalators feels like a bit of a cruel ask. It is a recipe for self-diagnosed misophonia.

It is not all Sturm und Drang, however. A handful of hidden gems can be found brimming on the edges of the exhibition (and isn’t this always the case?). Layla Vardo’s archival project Orders of Magnitude (2021), found in a nook opposite a colossal showcase by Civic Architecture, plays a series of sliced up video clips of television appearances by Sir David Attenborough, cut short just before he begins to speak about whatever wondrous place in the world he’s in. The ordered inhales chronologise these direct-to-camera addresses over a five-minute succession, from a then-young and dashing David in 1965 to a now nearly ninety-seven-year-old, who, like all of us, edges closer to making his last gasp. While impossible to miss, I can’t help but be reminded of Lou Hubbard’s piles of grey deflating inflatable walking frames lying dormant in the foyer on level three, Walkers with Dinosaurs (2021-23). The works jab at our subconscious sense of gradual demise.

A work that felt almost impossible to fully access without some God-tier level of navigation is George Egerton-Warburton’s mobiles. Three steel frames made from recycled farm machinery parts act as the support structures for a menagerie of hanging found and stolen materials haphazardly bound together (think a pair of Calvin Klein knickers penetrated by a wooden log, balancing Guzman y Gomez table numbers tied to a beam with a long, dirty, used UA airline strap). These static suspensions are impressive in their aesthetic collusions. A George favourite, titled Write-off (2022), was also the only work I found in Melbourne Now that actually smells. I fight the urge (as some kind of curatorial revolt) to wheel these out of the corridor and listen to them clang around in the neighbouring gallery spaces.

Around the corner, Claire Lambe’s newly commissioned video installation, Sudden Bursts of Nasty Laughter (2022-23) is a triumph, layered with cinematic and self-referential motifs. Her extensive experience in making sculpture lends itself to parts of the film showing us ambiguous bodily scenarios: a mountain-like “peak” is in fact a well-lit arse propped up by one of the actors lying on their back. In other moments, optical illusions occur where the visual effect presents the viewer with two shape interpretations, but only one of which can be maintained at a given moment. Take for example footage of the close-up crotch shot, where pale thighs and black underwear of a sitting subject suddenly appear as the profile of two naked breasts.

The audio cuts to a distinct sound of two women talking loudly over each other with thick British accents. This quickly turns into one of them egging on the other to play (“Oh goh arrrrn!”) a tender piano cover of Labi Siffre’s 1972 hit, My Song. All the while, we watch a topless Ryan McGinley-looking subject shot from the waist up riding effortlessly through a nondescript Demazin-blue sky.

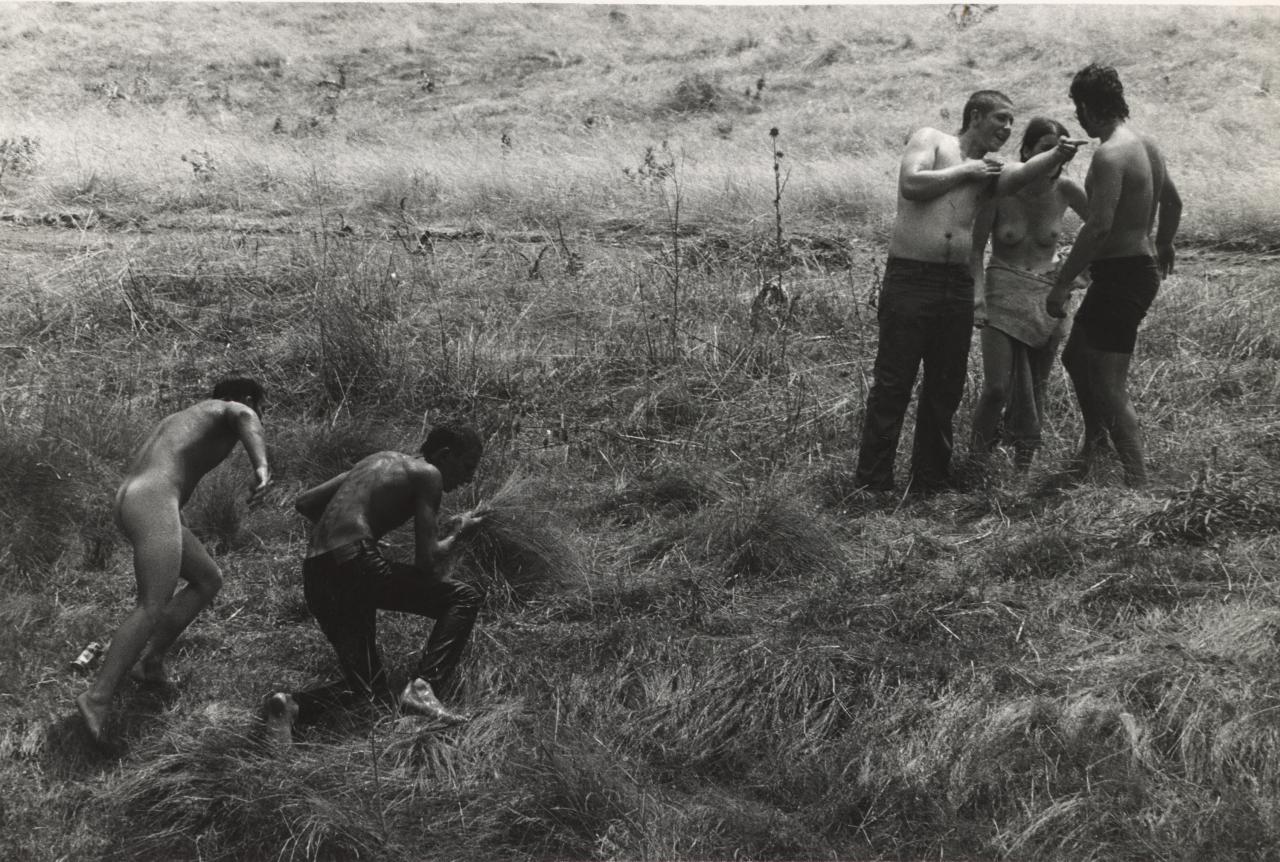

Blaring across the room from Lambe’s installation is British artist Mark Leckey’s Are you waiting (LED)(1997). It’s like a supersized GIF, playing a few seconds of a dude ecstatically dancing to music on loop. Are you waiting (LED) is one of five works from the NGV collection that Lambe curated as her chosen neighbours, the others being by Elwyn Dennis and Rennie Ellis. It is easy to connect these influential dots: she is the same generation as fellow Brit Leckey; shares a sense of mischief and cheek found in Ellis’s photographs, and the formal sensibilities of Dennis’s sculpture.

Like Lambe, Ruth Höflich’s newly commissioned work, Two Suns (2023), considers the NGV’s collection, but instead utilises the institution’s site specificity by filming in its back rooms and storage spaces. Several young artists (some of whom were taught by Höflich) appear, speaking and repeating phrases, performing gestures while moving in and around each other, as if acting out scenes from an unpublished play. Parts of the archive are shown briefly (at one point you may glimpse a rare artist book by Ed Ruscha) or are obscured by the very thing that protects them. While it’s challenging at best to hear the audio, the work ultimately feels completely analogous to the conditions of the exhibition itself: torn in half by the competing sensory assaults assembled by the attention economy.

Chelsea Hopper is a curator, writer and contributing editor at Memo. In 2022, she ran 99%, a gallery housed in the Nicholas Building.