Marlene Gilson

Anna Parlane

At first impression, the current exhibition of paintings by Wathaurung Elder Aunty Marlene Gilson at the Art Gallery of Ballarat is thoroughly charming. Gilson offers an Indigenous perspective on Australian history, using a delicate naïve style that evokes directness and simplicity. On reflection, I found that Gilson's history paintings are more complex than their picture-book appearance suggests. Originally installed as part of the Biennale of Australian Art, the exhibition has enjoyed an extended run as a stand-alone show.

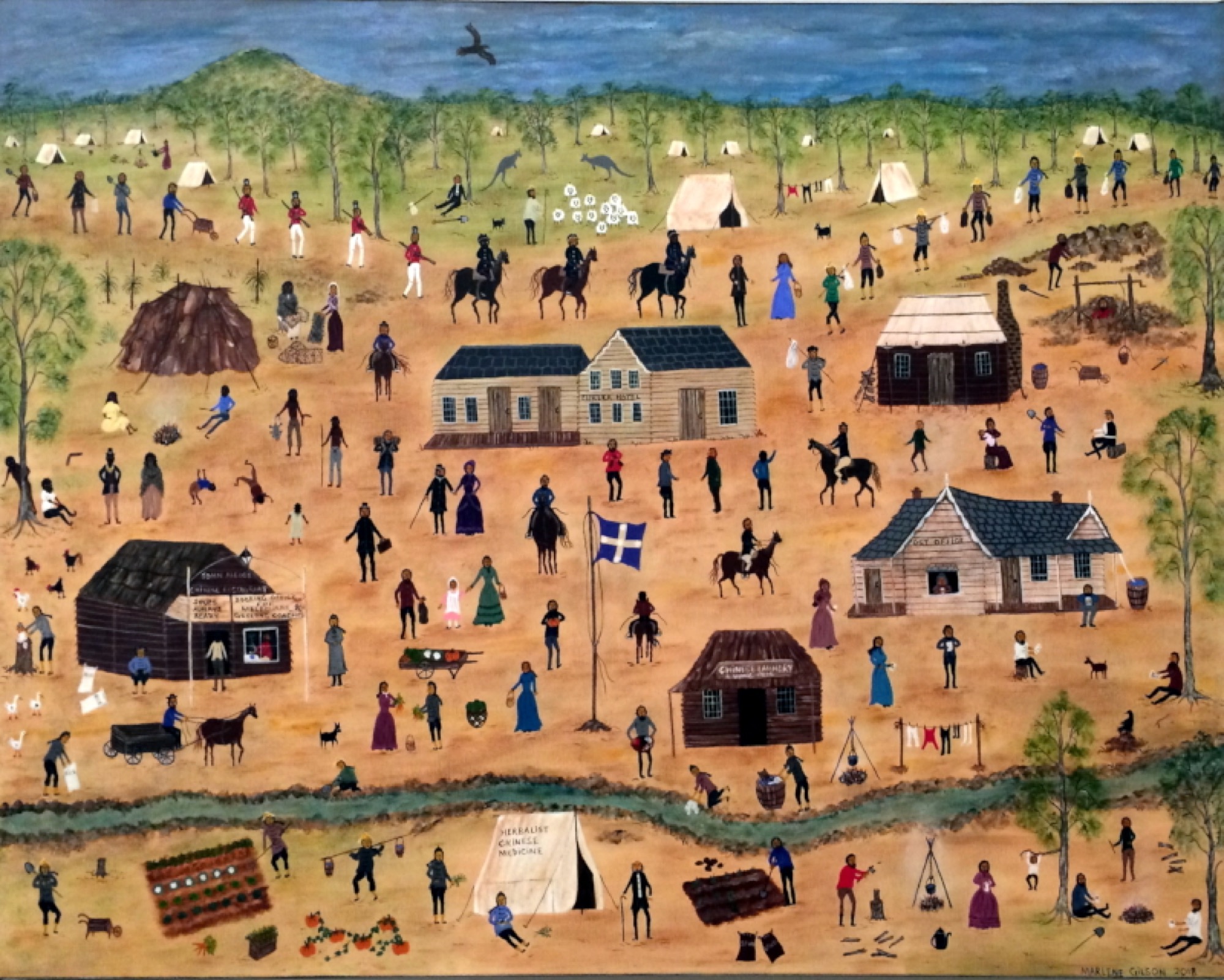

Unlike many artists who paint in a naïve style—in Australia, big names like Jenny Watson or Ian Abdulla, or younger artists like Chayni Henry come to mind—Gilson's works are not autobiographical. Since she began exhibiting in 2012, her exclusive focus has been Australia's early colonial histories, with a particular emphasis on the goldfields of Wathaurung Country. Gilson paints an expanded view of recorded settler histories, which pointedly includes those who were present but are underacknowledged in the records, such as Indigenous communities and Chinese immigrants. In Chinese on the Goldfields, 2018, for example, Gilson's great, great-grandfather, the legendary King Billy (recognisable by his trademark metal breastplate) stands beside John Alloo's Chinese Restaurant, which doubles as a booking office for coaches to Melbourne and Geelong. The painting depicts a hive of industrious activity: an Indigenous woman stitching possum-skin rugs fields interest from a white customer, Chinese market gardeners toil over neat-as-a-pin gardens and sell their produce, immigrant miners sit outside the post office and read letters from home. Gilson's point is clear: Australian society during the early colonial period was a multi-cultural affair, its diversity stitched together by both social and economic connections.

Gilson's method is to expand on or embellish stories from the archive, or sometimes pictures made by European artists. The Landing, 2018, for example, recalls the Samuel Calvert engraving Captain Cook Taking Possession of the Australian Continent on Behalf of the British Crown, AD 1770, published in the Illustrated Sydney News in 1865. Calvert's print, after a lost painting by John Gilfillan, shows Cook and his officers ceremoniously removing their hats as the Union Jack is raised on a flagpole. A band is playing, uniformed soldiers perform a seven-gun salute, and an Aboriginal man wearing European clothing deferentially offers a tray of drinks to the officers. The other Aboriginal people in the image are—it is implied—so startled by the sound of gunfire that they cower in the bushes at Cook's feet or flee in terror across the distant hillsides.

It's worth noting that this image also had a re-run in Gordon Bennett's Possession Island, 1991. Calvert's print's orphan status—a copy of a lost original—no doubt appealed to Bennett's postmodern sensibilities. Whereas Bennett was concerned to expose the fictionality of pictures that have, over time, played the role of historical documentation, Gilson deploys the artistic license of a traditional history painter. In precisely the same way that the Gilfillan/Calvert picture embellished scanty historical details into a fleshed-out narrative scene, Gilson imaginatively renders in paint the Indigenous lives and practices that went undocumented by European observers.

The Landing depicts a moment shortly following the one Calvert etched into history. The drinks have been passed around, the band continues to play and the new European arrivals are having a jolly time. So are the Indigenous people that Gilson shows us were cropped out of Gilfillan's and Calvert's representation, myopically focused, as it was, on Cook as primary protagonist. Immediately adjacent to the site where Cook's men are busily setting up camp, Aboriginal families are doing the same. Men bring in their catch from a fishing expedition, while another hunts a kangaroo with a boomerang. Kids are having a game of football while their elders prepare food or sit and have a yarn by the fire.

Gilson's work has clear political significance as a counter-narrative to the univocal and blinkered settler-colonial histories that enable, for example, so many Australians to celebrate on 26 January. This, in addition to the undeniable charm of her crowded, busy scenes, with their multiple storylines and details that are often sweet or funny, has contributed to her rapid success as an artist. However, I think there's more at play in Gilson's paintings than feel-good revisionist history. Her works are distinguished by their sheer volume of accumulated detail, and—as an exhibition of this size reveals—the artist's use of repetition. In these paintings, history is not understood as a linear sequence of significant events.

Gilson's typically elevated point of view, and her focus on the minutiae of daily life, creates a Brueghel-like doll's house world. We are given a bird's-eye view of multiple intersecting lives and narratives, a synchronic slice of history. Unlike an event-centred European perspective that distills history into a series of 'pregnant moments', Gilson arranges her atomised history into an all-over composition that renders multiple concurrent stories equivalent in significance. Using the European history of symbolic events or figures as her starting point (Cook's arrival, the William Buckley story, the Eureka Stockade), Gilson relativises these events and figures by making them one of many.

This atomised perspective undoes the 'grand narratives' of European colonial modernity, but another effect is to relativise the narrative told by contemporary Indigenous activism—in which instances of dispossession, massacres and violence cohere into an epic, nightmare history of the systematic slaughter and disenfranchisement of Aboriginal Australians. Gilson's work often alludes to colonial violence, most explicitly in this exhibition in Mumbowran, 2018, where she describes the staggering injustices of the settler-colonial justice inflicted on the Wathaurung man Mumbowran. Gilson shows her protagonist in chains, surrounded by armed soldiers, while the Aboriginal people gathered nearby shout and gesticulate their rage and frustration. The disenfranchisement of Aboriginal communities and the destruction of traditional hunting grounds is also present as a latent fact in Corroboree, 2018, which depicts the performance of a ritual dance for money. Corroboree stands in contrast to Gilson's rendering of arcadian plenitude in Black Swamp–Lake Wendouree, 2016, which is the only large painting in the exhibition exclusively to depict Indigenous people. However, these stories are, as in all of Gilson's paintings, presented as one among many. Outside the orbit of the dramatic scene unfolding around Mumbowran, life goes on: people catch fish, gather firewood, perform their daily tasks.

Instances of repetition between Gilson's paintings reinforce this sense of continuity. The most obvious repetition, because the most consistent, is the appearance of the Kulin ancestral beings Bunjil and Waa, the wedge-tailed eagle and the crow, in all of Gilson's larger paintings. Bunjil is easy to spot, soaring above the activity on the ground, while Waa usually appears perched on a rock or tree stump, keeping an eye on things. Finding him amidst the other figures quickly becomes like a game of 'where's Wally?' The persistence of these two figures in Gilson's work is, however, much more than a cute quirk. Affiliation with either Bunjil or Waa defines the moiety structure of Wathaurung society, as it does for the other Nations of the Kulin alliance. The ancestral beings, therefore, are much more than creator figures whose agency is confined to an origin point in the past: they are fundamental to family structures, the cross-generational inheritance of connection to Country, and the social and political fabric of everyday life. The continuous and ongoing presence of Bunjil and Waa demonstrates that the Dreaming is here and now—it is a lived system of relations and connections—as well as there and then.

Gilson's paintings adopt a historical perspective that has both synchronic and diachronic aspects. Each painting is a snapshot of complex synchronicity, showing the busy tangle of lives lived concurrently. But by repeating her hieroglyph-like figures between paintings, Gilson also creates a diachronic sense of continuity across time—without stretching past and present into a linear chronology. The major clue to this realisation, for me, was learning that Gilson habitually paints her friends and family members into her historical scenes. Collapsing the distinction between past and present—between the here-and-now and the there-and-then—these works offer an intricate view of history no less grand than the linear narratives they displace.

Anna is a writer and occasional curator based in Melbourne. She is currently finishing a PhD at Melbourne University, and was previously assistant curator at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.