Margel Hinder: Modern in Motion

Jane Eckett

To anyone in Australia with a passing interest in modern sculpture, Margel Hinder (1906–1995) has long stood out in a league of her own. From the vitalist spirit of her early wood carvings of the 1930s and 1940s, to her pioneering constructivist mobiles of the 1950s, and finally her monumental abstract architectural sculptures and fountains of the 1960s and ‘70s, she was consistently a leader in the field. Her younger peers in the 1960s hailed her as one. Lenton Parr opened his book Sculpture (1961), for the Longman’s ‘Arts in Australia’ series, with a photograph of her work for the Western Assurance Company in Sydney, writing of such successfully integrated architectural sculpture as having an “unrivalled power to enrich our lives and ennoble our cities” and giving Hinder two entries in the book—the only sculptor to be afforded such space. In 1964 Gordon Thomson regarded this same work as “still by far the best piece of architectural sculpture in the country”. Similarly, in an article for Hemisphere, in February 1963, Clement Meadmore positioned Hinder as the only mature sculptor to have received commissions in Sydney, ranking her with Klippel, who had by then left for the United States. Despite this professional recognition, her work has only ever been exhibited in group shows or with that of her husband Frank Hinder. This exhibition, organised jointly by the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) and Heide, is the first dedicated Margel Hinder retrospective.

The three main stages of Hinder’s career are given balanced representation. This is no mean feat for the retrospective of a public sculptor, whose major commissions cannot be physically included but only documented through photographs and maquettes. An innovative feature is the inclusion of two immersive environments, created by Andrew Yip, which convincingly simulate the original architectural contexts and viewing experiences of two of Hinder’s major commissions: Newcastle’s Civic Park Fountain (1961–6) and Sydney’s Northpoint Fountain (1975). Two rooms at Heide are given over to these immersive video projections, with the Newcastle immersive occupying an entire wall and filling our field of vision with the spectacle of carefully choreographed arcs of water. The Northpoint immersive is smaller scaled but successfully conveys the work’s gentle cascade and kinetic rotation as it originally functioned, outside Northpoint shopping centre, before being relocated to Macquarie University in 1992.

For visitors entering the exhibition from the Albert and Barbara Tucker Gallery (with its current intriguing juxtaposition of Tucker’s electric light imagery with corresponding selections from Patrick Pound’s atlas-like photographic archive), a sequence of photographs, enlarged from originals held among Hinder’s papers at the AGNSW, line one wall of the rampway and introduce the subject. The selection interweaves the personal and the professional, in a manner reminiscent of Barbara Hepworth’s carefully curated Pictorial Autobiography (1970). Given Hinder’s respect for her British contemporary (only three years her senior), the comparison is perhaps deliberate. Alongside studio portraits are intimate snapshots of Hinder and her daughter Enid, Tucker’s photograph of Frank and Margel Hinder at a Contemporary Art Society (CAS) meeting, and professional shots of Hinder with tools in hand—mallet or oxyacetylene torch, depending on the period—at work on major commissions such as the Reserve Bank Sculpture in Sydney’s Martin Place.

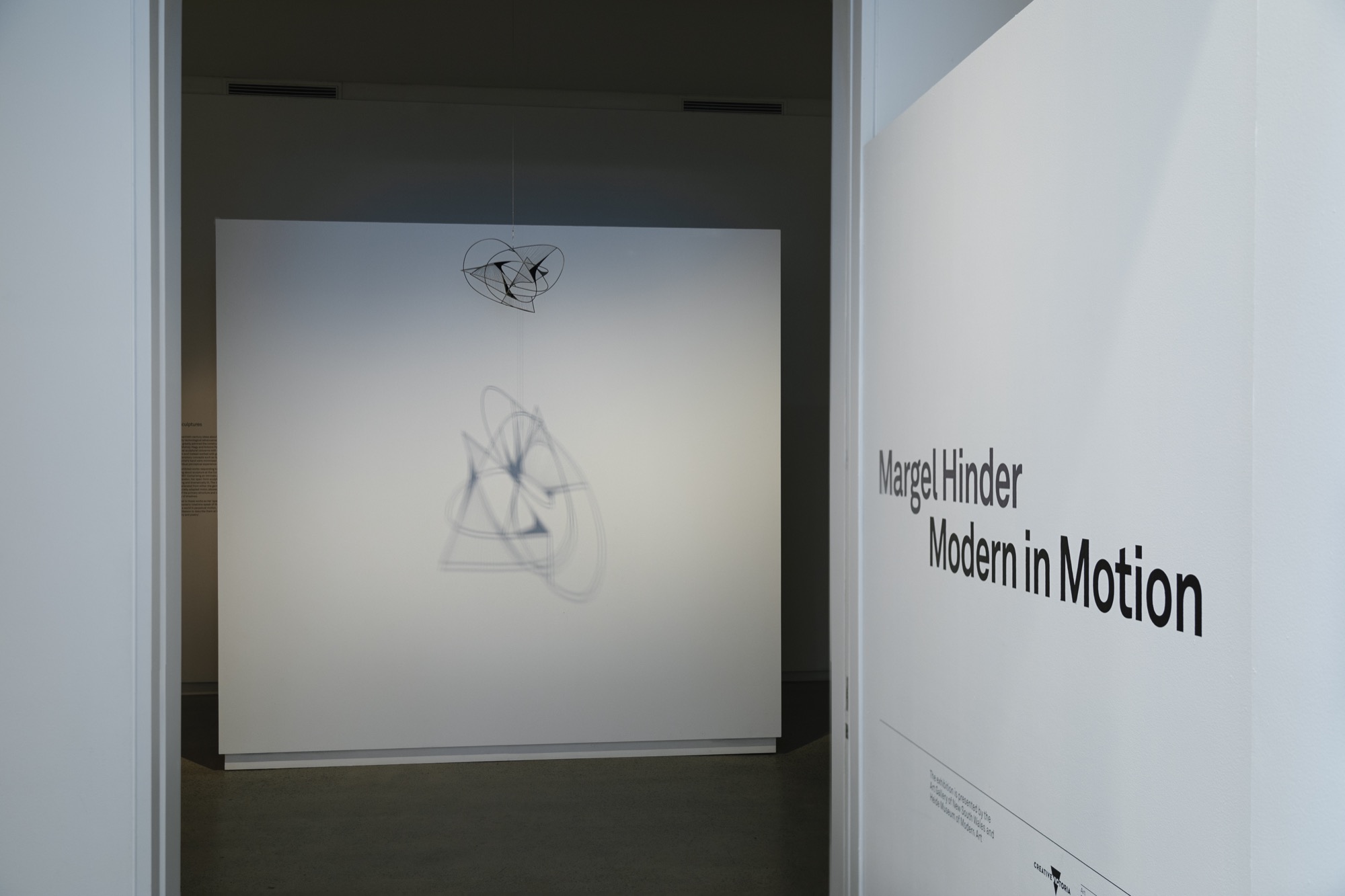

The first room of the exhibition is devoted to Hinder’s space-age rotating mobiles, a selection of wall-mounted wire constructions and a striking series of mid-1950s constructions in wire and hand-coloured Perspex. Revolving Construction (1957) takes centre stage, floating airily above the entrance and casting its magnified shifting shadow onto a large white freestanding wall. To the left, further spherical wire mobiles—Construction (c. 1954) and Model for Canberra Revolve (1961)—pivot mesmerically above two cases of maquettes: one containing smaller-scaled spherical mobiles and the other a dazzling array of small, silver-painted maquettes of soldered metal. Hinder retained these “lovely wiry things”, as she affectionately called them, in her home and studio as visual referents. Gifted in 2003 to the AGNSW by Hinder’s daughter—a result of retired curator Renee Free’s longstanding work with the family—the maquettes are often on display in Sydney but have been newly conserved for this exhibition.

Conservators from the AGNSW apparently contributed to the exhibition’s design. The presentation of open form constructed works dictates careful attention to lighting and cast shadows, while kinetic mobiles are subject to the movement of air — whether controlled by a fan or simply subject to ambient airflow. With access to a near-comprehensive body of Hinder’s work, as well as a large archive of papers, conservators worked on the principle that, insofar as Hinder’s intentions could never be precisely known, they could present the work in a manner she would have sanctioned. Given this, it is perplexing to find Construction (c. 1954) suspended before a white wall, when Denise Mimmocchi’s exhibition catalogue essay records that when it was first exhibited at the CAS it was “lit to her (Hinder’s) specifications against a black cloth”, creating “one of the most dramatic installations of modern sculpture in its day”. Indeed, for the initial installation of the exhibition at the AGNSW, it was hung before black-painted walls, but this decision was reversed for the Heide show.

Nevertheless, the small annex gallery devoted to Hinder’s carvings is arguably a more sympathetic installation than the larger room given to these works at the AGNSW. Here the works are presented against black walls, with each work spot-lit, heightening the dramatic shadows and the tactile qualities of wood and stone. Hinder’s carvings are indisputably good. They belong of course to the vitalist school that largely revived an otherwise moribund British sculpture in the 1930s and which attracted adherents around the world including Robert Klippel and Gerald Lewers in Sydney, Inge King in London (before emigrating to Australia), and Clifford Last and Norma Redpath in Melbourne. Her Pueblo Indian (1934) is a calm and empathetic study of the body’s load-bearing capacities, made shortly after her departure from Taos, New Mexico, while the later carvings, such as Movement (c. 1945) and Carving (1952), progress from abstracted natural forms suggestive of seed pods to more angular, constructivist forms.

The key transitional work from these carvings to the 1950s wire constructions, unfortunately destroyed and so present only as an archival photograph in a display case, was Hinder’s prize-winning maquette for the Unknown Political Prisoner (1952). This was her entry to a world-wide competition, touted at the time as a “sculpture Olympics”, organised by the Institute of Contemporary Art in London and secretly sponsored by the CIA as part of a Cold War strategy that positioned the West as progressive champions of abstract modernism. Hinder’s was one of fifty-six entries submitted from Australia, from which three (by Hinder, Tom Bass, and the now little-known John Joseph Bruhn) were sent to the Tate in London for the international judging. Hinder’s was awarded equal third among twelve overall winners selected from over three thousand entries worldwide. Her entry was a stringed abstract form with two “arms” that forked upwards before folding protectively inwards around a threaded wire structure that, through its cast shadows, accentuated rotation, space and light. This was to have been set in a spiralling recessed bowl, which viewers could walk into and around, the whole demonstrating the principles of dynamic symmetry that Hinder had learnt while studying under Emil Bisttram in America. It opened the way to her use of soldered wire, with her renowned series of wire mobiles beginning the next year.

The second gallery is devoted to her later works, which are heavier and often far more tactile than the 1950s constructions. Black Silhouette (1979) commands centre stage, its smooth black steel forms contrasting with the treetops framed by the window beyond and directing the eye towards the similarly horizontal forms of the Newcastle fountain that can be glimpsed in the adjoining room’s immersive environment. The horizontality of both works reads in terms of landscape and represents the antinomy of vertical monuments. Nearby, the claw-like steel forms of Six-Day War II (1973), made in response to the 1967 Arab-Israeli conflict, convey a palpable sense of menace even without its smaller counterpart, which is permanently installed in the Penrith Regional Gallery’s garden. Most of the other works in this room have a highly wrought texture, from the dripped copper alloy surface of the Maquette for Reserve Bank Sculpture (1962) to the knobbly texture—also in copper alloy—of the helmeted Green Garden Sculpture (1972). The monumentality and solemnity of these works call to mind Hepworth from the same era, prompting speculation as to whether Hinder would be more widely known had she lived anywhere other than Australia.

Comparisons are invidious, yet necessary. When Hinder arrived in Australia in 1934 she perceived the most advanced sculptor then working in Sydney to be Gerald Lewers, who had returned four years earlier from England where he had worked with John Skeaping and met Moore and Hepworth. Soon afterwards she also befriended Eleonore Lange, who arrived from Frankfurt in 1930 and whose unrealised Seraph of Light (maquette for a proposed memorial to Walter Duffield) (1934, NGA collection) inspired Hinder’s first forays into public art. In 1937 Lyndon Dadswell returned from his studies in England, the Slovakian Arthur Fleischmann arrived at the outbreak of war, Paul Beadle did likewise in 1944, and in the post-war years a younger generation who had trained under Dadswell at the East Sydney Tech came to the fore, including Robert Klippel, Tom Bass, Wendy Solling and Anita Aarons. In Melbourne, Ola Cohn and Clive Stephen were the most advanced of the pre-WW2 sculptors, while Danila Vassilieff, Clement Meadmore and the Centre Five sculptors Julius Kane, Inge King, Clifford Last, Norma Redpath, Lenton Parr, Vincas Jomantas and Teisutis Zikaras took the lead in the post-war era.

Hinder shares elements in common with all of these, yet somehow stands apart. In 1971 she wrote apologetically to Clifford Last: “I am not a true professional in the sense that you, Inge (King) and the others are(,) but more of an amateur, who through circumstances, from time to time loses my amateur standing to do a big commission”. Though self-deprecatingly modest, this perhaps explains Hinder’s relatively low profile. A committed and inspired modernist, with large-scale public commissions realised in Sydney, Newcastle and Canberra, her studio practice was nevertheless largely private, dedicated to developing large commissions rather than producing work for exhibition.

This has left her exposed to the vagaries of changing tastes in architecture and urban design, with works removed and relocated from their original context. Geoffrey Batchen, Oxford art historian and a distant relative of the Hinders, in a moving catalogue foreword, recalls the distress of Hinder’s Western Assurance sculpture being removed and dismembered in 1980 to make way for a new shopfront, and his own inexpert efforts to help reassemble the salvaged parts. Flagrant vandalism and the flouting of artist’s moral rights are sadly all too familiar in Australia, where very few public artworks of the 1960s remain in situ. All the more reason therefore to draw attention to Hinder’s practice through this long-overdue retrospective and to restore—albeit virtually—her public works to their original contexts.

Jane Eckett is a Postdoctoral Research Associate teaching nineteenth and twentieth-century art history at the University of Melbourne.