Marcus McKenzie, The Crying Room

Chelsea Hopper

I’m on Zoom again. This time it’s not for a meeting or to teach but to watch The Crying Room, a forty-minute livestream performance by artist Marcus Ian McKenzie. In a promotional video for the performance, McKenzie explains that a crying room is “a small room you have at the back of theatres and churches where you can go if you are crying or making noise and you are disturbing a congregation or an audience”. And so, as he eventually points out to us, a crying room is a lot like Zoom.

The Crying Room was part of the Arts Centre Melbourne’s coveted Take Over! commission, which funded McKenzie—along with nine other artists—to work (and perform) at/from home. The performance was held over three separate showings (meetings?) in partnership with Melbourne Fringe.

Before the performance begins, the other participants (lets also call them audience members) slowly log in, mute themselves and quickly turn their videos off. The only person who doesn’t is a man sitting in his car (I can see the seatbelt) with distinctive white Apple earphones dangling from his ears. He is audibly shuffling around unaware that he’s still unmuted. As he is the only face among the sea of gridded black boxes full of identifiable names, the experience of staring into my screen at him grinning is slightly disruptive. The first chat notification pops up from the very same keen onlooker commenting, “I’m ready to cry!!!”. This is the moment when I worry that I’ll have to participate in some way, but I get distracted hurrying about my apartment to find my partner’s pair of fancy headphones as a prompt pops up on the screen that “headphones are recommended for this performance”.

McKenzie shares his screen and my computer’s desktop automatically fills with his. There is darkness, and mumbling sounds erupt in my headphones evocative of a slowed-down audio track of crashing ocean waves. A quote from the prologue of Donna Tartt’s debut novel The Secret History pops up, “This is the only story I will ever be able to tell”. I haven’t read the novel, but this simple line speaks volumes.

As the text disappears, a glowing logo for ‘Club Greg’ blinks and spins. McKenzie says it is a made-up club rumoured to have “affiliations with arms dealing syndicates”. Before I knew of this origin story, I surmise it’s a small underground production company that perhaps sponsored McKenzie’s performance, along with the popular Monster Energy drink where the brand logo’s vibrant green typeface is appropriated to advertise the subsequent opening credit “Marcus McKenzie Acter”. No, that isn’t a typo. The “e” is deliberately tongue in cheek and points to how McKenzie associates himself with the category actor—a title that can often tightly stick to one coming from a theatre background. Having seen McKenzie’s performances over the past few years, the label “artist”, which he eventually gives himself later on in the performance, feels more appropriate to me. Although it’s hard not to think that McKenzie is selling himself short here. Like the caterpillar who makes an elaborate hat out of its own discarded heads, he too is constantly wearing and balancing multiple roles: artist, actor, sound designer, performer, producer, writer, creator and maker. I’m yet to find a word that’s sufficient.

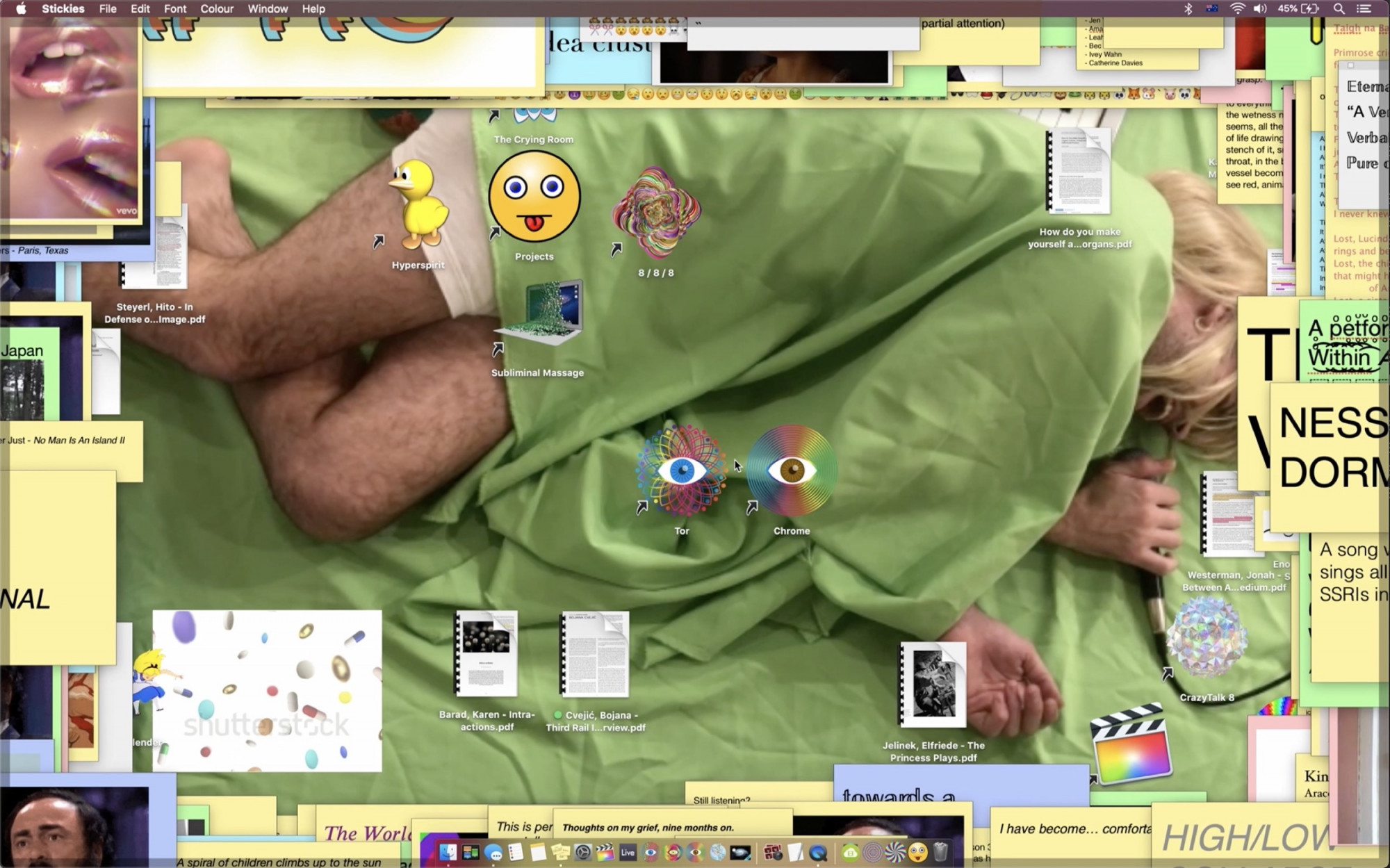

The sound of heavy rain transitions into ambient noise, and we finally see McKenzie sitting cross-legged on his lounge room floor surrounded by lit candles and warm red neon lights. He begins an instructional meditation gleaned from Subliminal Massage—his 2019 performance held at Steps Gallery and memorable for its self-help guru-cum-performer who monologues, breaks persona and eventually dances badly to rave music. Imagine a cult leader with a taste for club life. While it’s the same scripted meditation, I still close my eyes. The instructions get weirder and the question of what to do and how seriously to take it gets harder to answer. At one point, he guides us: “For the remainder of the showing, you may choose any of the following configurations: eyes open, imagining eyes open; eyes closed, imagining eyes closed; eyes open, imagining eyes closed; eyes closed, imagining eyes open”. Then the final instruction, “If you do not have access to eyes or an imagination, just do whatever is comfortable”. I can’t hear anyone laughing in the Zoom or see any lol’s in the chat as I’m imagining eyes open; eyes closed.

McKenzie ups the absurdity, calmly directing us: “Imagine you are a fish. Good. Imagine you are a frog. Good. It is fun, isn’t it?” All the while the audio track humming away reminds me of the brooding synths in composer Angelo Badalamenti’s Laura Palmer’s Theme, the iconic track from David Lynch’s TV series Twin Peaks. The hauntingly cinematic feel is coupled with the humour of an early Monty Python sketch prompts visual cues of a Surrealist painting. At this point, I’m still convinced McKenzie’s performance is live. After all, that’s how the performance was advertised, but the dead giveaway is the subtitles and his voice falling out of synch. How exactly has he done this? There’s audio/visual manipulation occurring, but I’m too caught up in the on-screen antics so for now I forget about the politics of looking. The voiceover stops, and he gets up to turn on the lamps in his living room. The spiritual transcending is cut short and McKenzie changes character (only slightly) by donning a scruffy blonde wig shoved under a cap. He grabs the camera and starts directly speaking to us up close like we’re on a FaceTime call, running through housekeeping rules, encouraging us to turn our videos on, and eventually gives context to The Crying Room.

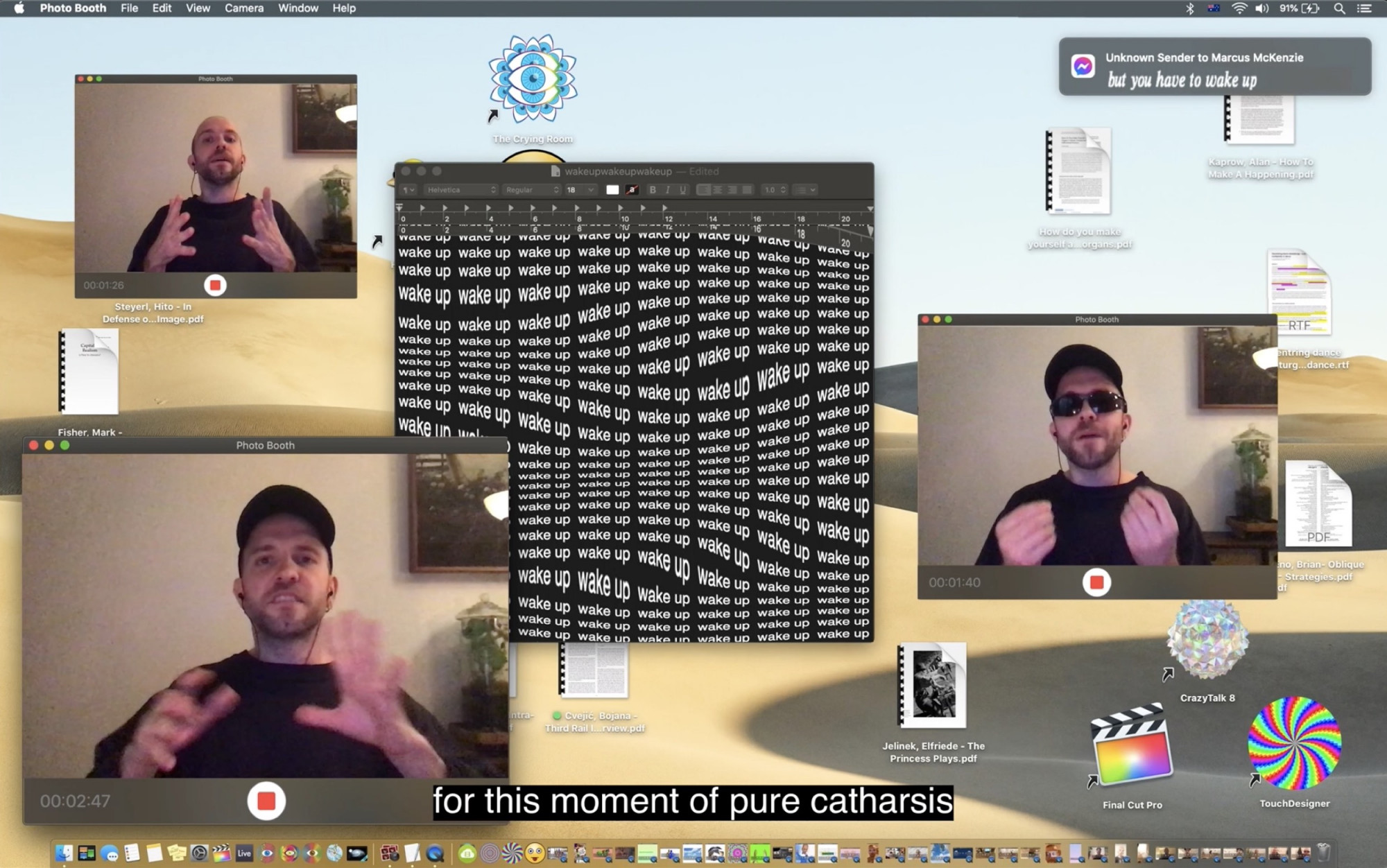

McKenzie explains his initial intentions to gain access to a crying room located at the Art Centre Melbourne. But due to restrictions, aptly described in the performance as “an unforeseen force majeure”, this wish became impossible to grant. As he launches into elaborating on the “why” of the work (imagine if all artists did this), he is suddenly interrupted by a noise in the distance, out of the frame. He drops his camera, and the frame quickly scrambles into focus the hallway in front of his apartment’s front door. We’re led down to a flight of stairs where we see another version of McKenzie wearing the same garb holding up an iPhone to his brow playing a stock video of a man’s blinking eyes. The voiceover is back, repeatedly saying “wake up”. The doppelganger smothers the camera frame and for a moment the video appears frozen. Another digital layer is peeled off, as it becomes apparent it’s just a prerecording and the video is minimised to show McKenzie’s computer desktop full of downloaded pdfs of texts by Mark Fisher, Hito Steyerl, Allan Kaprow, Brian Eno and Karen Barad, to name a few.

As I try to register the other icons on the desktop, a TextEdit box expands and the sound of incessant typing draws my focus on the phrase, “wake up”, eventually getting copied and pasted over and over again. Another video appears of McKenzie who begins to narrate a period of his life around this time last year (retrospectively in late November) of obsessively watching recorded performances on YouTube of the final aria ‘Nessun Dorma’ in the last act of Puccini’s opera Turandot, famously sung by the well-loved tenor Luciano Pavarotti. In 1990, Pavarotti’s televised performance of Nessun Dorma at the FIFA World Cup in Milan to a packed crowd was a populist shift in the face of opera, captivating a global audience. Pavarotti transformed it into one of the most well-known Italian arias of all time. McKenzie describes why people know the aria so well to this day. It is “inextricably linked with a memory, with an intensity”. In the video he continues to explain that, by coincidence, Opera Australia were remounting their production of Turandot in Melbourne at the time of his birthday in early December last year. He decides to go for the occasion. What follows is McKenzie articulating how he received news from his parents, midway into the opera; although it’s never made explicit what the news is exactly about (it’s mentioned in the promotional video made by McKenzie for The Crying Room that it was the day he found out about his brother’s death), it ultimately results in a failure to see the final act of Turandot. For me, to relay the finer details of this part of the performance does it a disservice: the best I can say is that it’s heartbreaking. It is a significant moment that McKenzie shares this with us without falling into the trap of cliché or appearing overly sentimental.

There are many parallels to draw between Puccini’s last opera and McKenzie’s performance. While the final act of Turandot was completed, Puccini left the opera unfinished at the time of his death: two years later Italian composer Franco Alfano completed it. Although McKenzie is of course still alive, the content of The Crying Room feels like the years between Puccini’s death and his piles of manuscripts and notes have now been chaotically stitched together creating and producing literally different versions of himself. It seems there are endless ways to approach or make associations with McKenzie’s chosen subject matter and he seeks to try them all out at once.

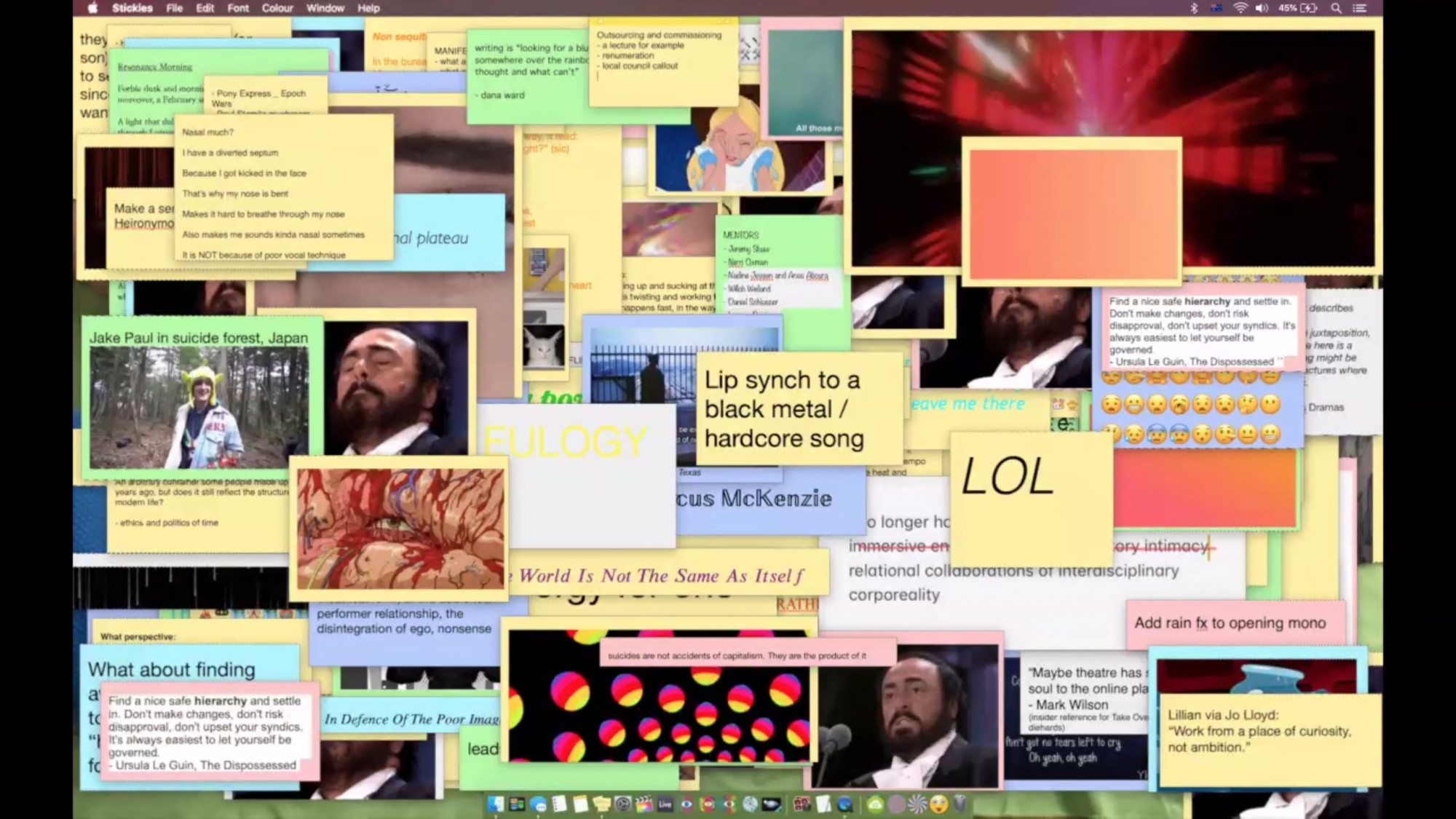

McKenzie suddenly fractures our attention by expanding a plethora of recorded videos (all of himself) hidden in the menu bar on the computer desktop. They begin to play all at once, flooding the screen, making it audibly difficult to listen to any one version of McKenzie. At one point I can just make him out saying “I’m going a bit crazy”, but an eruption of even more videos taken from documented developments, previous recorded performances, screenshots, memes, hundreds of stickies and gifs continue to overflow like a virus viciously attacking your slightly out of date MacBook. Are we witnessing a cluster-fucked grief spiral? Eventually the screen shifts to another where a web browser is open to a reddit search for suicide watch; another tab is open to a Wiki how-to on “making your eyes water”; and a Google Image search of “crying images”. I can hear McKenzie crying and the wailing splits open the screen to a bird’s eye view of him on the floor wrapped in a stretchy green screen sheet weeping and wearing another cheap blonde wig. It’s not long until the sound of his agonising cries starts to autotune reminiscent of the famous autotuned “Best Cry Ever” meme.

Slowed-down found footage of a lone ocean liner crashing into deep sea waves filters slowly into the screen. The ship leads us into darkness where McKenzie recites an epic poem, guiding us through to the next phase of the performance titled “INTERVAL”. We see McKenzie for the last time sitting in front of his apartment’s balcony stuffed with an abundance of healthy-looking hanging pot plants. Once again, as he begins to talk—politely thanking us for being with him—his face suddenly freezes, crushing into tiny pixels—it’s another glitch pulling us back into an alternate constructed reality. The optics of his apartment erode and fall into the visuals—hallmark distortions of an LSD trip. Strobing lights backed by rave sirens and heavy electronic beats expel us straight back into the calming sounds of heavy rainfall. What follows is blinking text detailing a story of McKenzie stumbling into a theatre in Berlin feeling sick and being taken into a “Weinen Zimmer” (German for “Crying Room”)—at last.

The credits roll. There’s no cue to applaud, but a number of participants unmute themselves and begin screaming and clapping. The chat lights up with comments, and McKenzie, who has been there all along, types “Thanks so much everyone”. Now that the Zoom meeting, The Crying Room, has closed, the live performance is exposed to the same conditions of any art exhibition or theatre production. What’s left is the documentation and the personal recollections of those who saw it. And that’s the catch, right? You’ve got to see it before it disappears.

McKenzie’s practice continues to wangle language, performance, narrative and humour into intense and memorable feats I feel privileged to witness. It is extraordinary to me, since we’ve been able to meet people and leave our houses, that McKenzie created The Crying Room during a year of such repressive and strange circumstances—all in the confines of his apartment. That, and grappling with the long and winding process of grieving that can completely alter our own conception of time, filling us with tears.

Chelsea Hopper is a writer, editor and curator based in Narrm/Melbourne.