Lucina Lane and Nigel Lendon: Teach the Kids to Strike

Giles Fielke

I’ve not noticed the terazzo tiles on the floor of Neon Parc’s city gallery. And I’ve been visiting shows at the Bourke Street space for years now. It took Lucina Lane and Nigel Lendon’s collaborative exhibition Teach the kids to strike for me to look hard at just how extraordinarily worn the floors really are. When I ask gallerist Geoff Newton about this, he unpretentiously admits that the floor was the main reason he chose the small, first-floor space over a decade ago.

I love Neon Parc – this is no secret. Exhibitions there often easily swing between the sublime and the ridiculous, and just as swiftly back again. The stairwell to the gallery is lit by a Franz West hanging lamp that is sometimes incorporated into groups shows. Three years ago Newton opened a much larger space in Tinning Street, Brunswick. The first show there accommodated a suite of oversized and warped paintings by Dale Frank, reflecting the Melbourne art scene as some kind of grotesque miscreation. I recently saw a Virgin Airlines commercial that lightly jabs at the Melbourne hipster-art mafia in the Sydney Airport. There was something singularly quaint about the cutting use of such a marginal trope to sell tourism off the back of the inter-city culture wars. Lane and Lendon’s use of Neon Parc’s smaller space, situated as it is above a defunct entrance to a Bourke Street newsagent and effectively the entrance to a large multi-story carpark, is transformative in that it focuses our sense of the place.

The collaboration between these two artists comes despite a seemingly yawning gap in their respective ages and therefore their ‘careers’ as artists. Lane commits to assisting, and in a strange sense rehabilitating, works first produced by Lendon between 1967 and 1970, almost a quarter of a century before she was born in 1991. For his part Lendon, a seasoned traveller of the Australian post-conceptual art landscape, provides a context for Lane’s emerging practice of playfully analytic excavations of painting and its models after conceptualism. In doing this he becomes a resolute foil, one only possible for someone who was there the first time around.

At the centre of the exhibition is a huge work hung on the gallery’s eastern wall by Lane alone, titled Fallow Field, which the roomsheet notes as working in the idiom of Colour Field painting. The found, mouldering hessian stretched within an inch of its life against the cold cut steel scaffolding suggested something far different to me, however. Georges Didi-Huberman’s 1984 essay, ‘The Index of the Absent Wound’, takes the Shroud of Turin at its face value; if it is to be consecrated, the stain needs to be ordained as an image of the son of God, an index of unearthly appearance. Lane’s index is the godless waste of industry, and these stains produce an image of profanation - of a world with no gods, only masters.

Born in Adelaide in 1944, Lendon initially studied medicine before becoming a sculptor whose early works were admired and selected for inclusion by John Stringer in the landmark 1968 exhibition The Field. He therefore currently has other of his early works on display just down the road from Neon Parc, at the NGV Australia’s The Field Revisited. The works lie open, as Lane’s work suggests; the fallow field is the perennial practice of painting as the master discourse for art as such. If this seems too bold, perhaps it is almost a provocation: what art has emerged that could challenge painting’s claim to absolute liberalism, of subjective freedom and also of individuality through authorship. Architecture, for one, is clearly beholden to the vicissitudes of corporate interest. That painting can escape this fate only makes it more desirable.

Also a curator and historian, Lendon’s encounter and association with the Art & Language group in New York and London following a Harkness Fellowship in 1974 lends his work an almost militantly utopian facet that has often had to weather the fluctuations of taste and tradition in Australian art over the years. Immediately, therefore, Teach the kids to strike exudes the sense of some kind of knowledge-transfer between the generations. At the centre of the room is an old steel and pleather fold-down school bench. On a couple of the seats a scatter of anonymous and blank aluminium coins gives the appearance of a cheaper kind of exchange. They fuck you up, your mum and dad – this is the crux of the premiss: the generations, the older avant-garde, will unfortunately have to have something to do with the new. The constructivist models that anchor Lendon’s work alongside the innovations of the historical avant-garde have furthermore often grated against the kind of social art history he has practised in more recent years – his avid collection of Afghan rugs is a testament to his interest in the visual iconography of the US ‘War on Terror’ as depicted for the ‘West’ from, or by, the ‘East’ – with their woven depictions of drones sewn amongst the more common grammers and tessellated geometric motifs, abstractions from longer histories of the region.

In essence, the dregs of modernism are here being re-used, hashed and ‘up-cycled’ for another go: abstraction, defamiliarisation, orientalism and provincialism. Like squeezing blood from a stone, the death of modernism still has something left to exploit: this is the tired discourse on refinement that contemporary artists like Amy Sillman still speak of when considering the ‘newly enthusiastic form of painting as a nudie activity,’ as opposed to a simply ejaculatory stance. Finally AbEx could be released from the vicissitudes of gender. Gender, as a fading signifier, has been relentlessly foregrounded in Lane’s practice – often against her best wishes. As one of the few emerging women artists who have been given the space to show regularly at Neon Parc, Lane has nevertheless continually suffered the indignity of being dragged for her serious intent. As a painter with work to do, her projects have often found themselves the targets of lazy jabs mostly posted online about representation and personal politics.

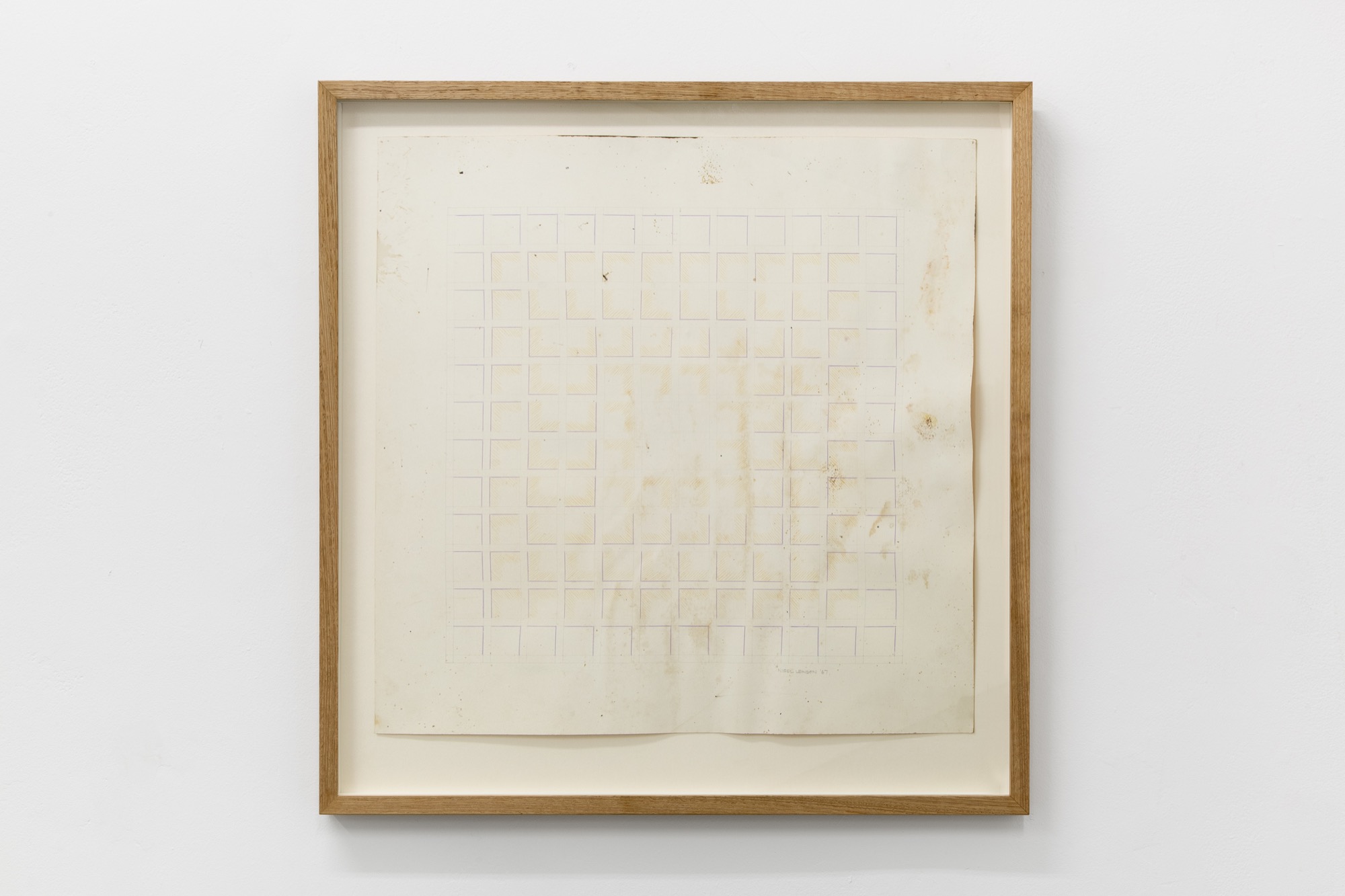

The Lane/Lendon collaboration began in the La Trobe Valley a few years ago. Visitor Visitor was the result of a residency Lane completed at the Gippsland Centre for Art and Design in late 2016. In many ways Teach the kids to strike is an elaboration of that first encounter. The art school, between Morwell and the Churchill Big Cigar on the Monash Highway, now administered by Federation University, was once home to a radically provincial cohort that included Lendon as a founder in the early 1970s, prior to his flight from Australia to the centres of the post-war ‘art world’. Interestingly, Lendon’s re-discovered, gridded serial composition in pencil, from 1967, was installed there under the title Yinnar Shroud. Yinnar is a nearby town in the valley named for the local indigenous word for woman. At Neon Parc it appears again, now co-credited with Lane under the title Bump (1967-2018).

Again the strange tension between the sanctification of minimalism and its profanation as waste (the work is badly water-damaged and stained) seems to float to the surface as a social engagement. Instead of the clean lines provided by the powdercoated steel of Lendon and Lane’s Untitled Wall Structure 1970-2018 and the two Untitled Table Structures 1970-2018on the floor of Neon Parc’s office (the same works also appeared in the Gippsland show two years ago, sans powdercoating), the decrepitude of Bump, Fallow Field, and the eponymous work in the show, Teach the kids to strike (the school bench with coins), suggests an archaeological approach to minimalism as historical material. This material is to be examined and analysed, as if the sanctified era (the golden jubilee celebrations continue unabated for the 68ers despite more pressing contemporary events) now presents an iteration of the horror vacui – instead of a Loosian eradication of ornament, minimalism retrospectively appears today as an anxiously iterated shroud for modernism. This is what Lane appears to be doing to Lendon’s work, and vice-versa – undoing, rather, the common assumption of a finish fetish, an alien object inserted into a cultural vacuum. In fact, the opposite is the case: the horrors of the 20th century needed a new type of ornamentation, and in this way the works can be productively compared to the shrouded monuments obsessed over by other Australian artists, like Callum Morton, or Tom Nicholson perhaps, rather than members of the formalist Field gang.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s the fetishisation of disappearance was on the horizon of a period suffering from an overabundance of visibility. Today that seems more true than it did then. But how does one map this disappearance when it was already foregrounded by the blank statements appearing at the end of modernism? What is the responsibility that people like Ian Burn and Terry Smith appealed to, with their elaborations on provincialism, in a period where no-one had anything to worry about but themselves? Lane seems to be concerned with the possibility that disappearance, or the zero point for the work, could act as a hinge for revealing the historical resonances of these works as indexing a particular moment. But what does this say about contemporary art? Perhaps that it is about asking the same questions.

In this way the figure of Burn, whose estate is represented in Brisbane by Milani Gallery, also home to Lendon’s work, is perhaps a figure whose writing on contemporary Australian art – until his untimely death in 1993 – can help to unpack the complex mix of motifs and references that can be found collecting at the edges of Lane and Lendon’s cooly spare production and preparation of the works included in Teach the kids to strike. Burn and Lendon’s essay for The Field Now, the 80s re-visitation of the landmark show at Heide (which recently closed Less Is More, its revisitation of minimalism in Australian art), was titled ‘Purity, Style, Amnesia’. In it they state that ‘the contradictory character of art in Australia produces a “distancing effect” which mediates any stylistic or intellectual dependency’. This, they argue, is the grounds for Australian art’s originality.

It is distance that Lane appears to want to exploit with these works, by convincing Lendon to powder-coat his Anthony Caro-esque table-sculpture miniatures, and the environmental, Flavin-like ‘wall structure’ poles white, Lane proposes a referential gesture that covers and preserves the idea of ‘gestalt’ art as only another moment of ‘Western’ aesthetic hubris. Now it appears ready for an historical examination, the dominant condition of contemporary art is looking back. The show closes today, so get there fast, before these works are returned to the mausoleum. And even if all you can see is the terrazzo on the floor. Otherwise, Lane and Lendon open another show at Caves in the Nicholas Building next Friday, the 22nd of June.

Giles Fielke is a writer and musician working at Monash University and the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.

Title image: Lucina Lane and Nigel Lendon, Teach the kids to strike. Photo: Christo Crocker)