Lots of art forms in madness

Amy May Stuart

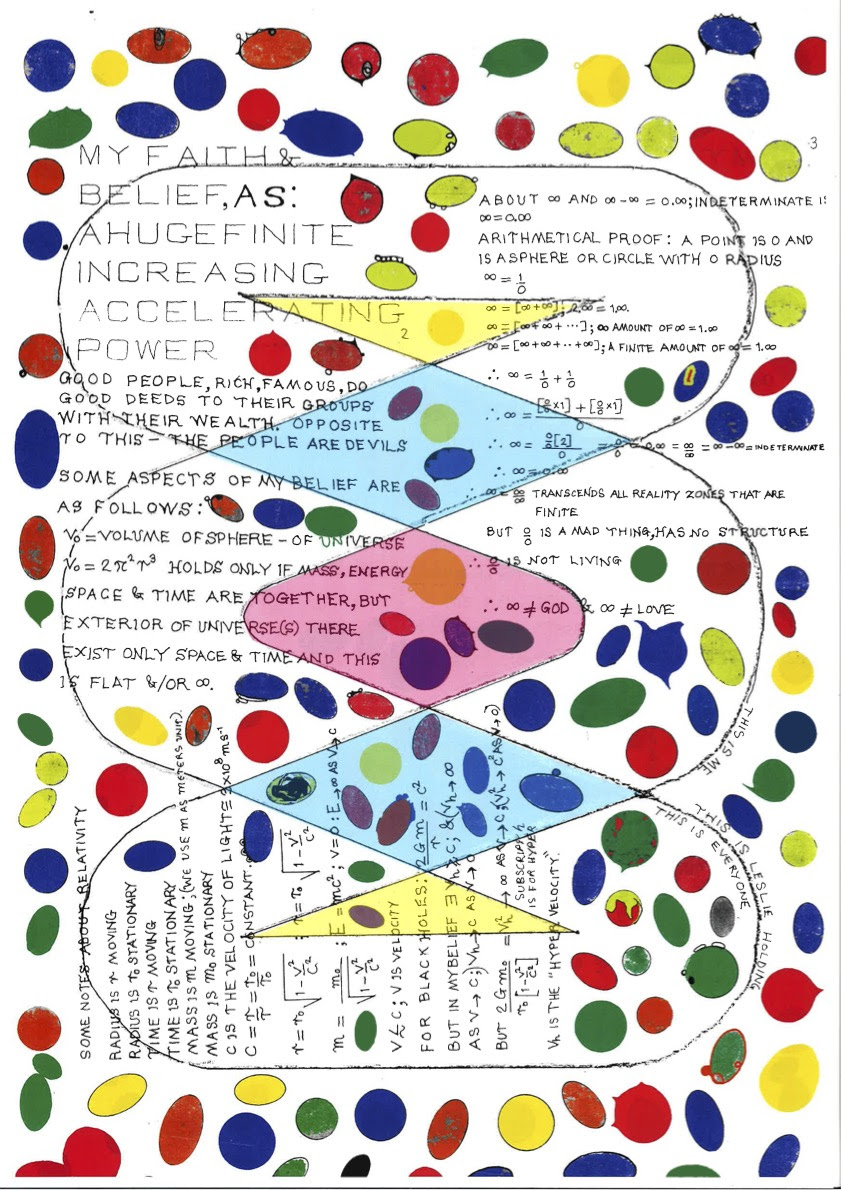

Lots of art forms in madness is Leslie Holding’s first solo exhibition. Born in former Yugoslavia in 1952, Holding describes himself as an “abstract surrealist artist, fascinated by dreamscapes and imagery of rural and metropolitan areas.” This note serves as an apt description of the exhibition itself, which extends across all three gallery spaces at Seventh and contains a prodigious amount of work, ranging from figurative landscapes and domestic interiors to all-over compositions of geometric abstraction, laden with Holding’s idiosyncratic lexicon of motifs. As indicated by the drawing reproduced for the exhibition invitation, the show is also a demonstration of Holding’s personal belief system—what he describes as “A HUGE FINITE INCREASING ACCELERATING POWER”—in which a God and conceptions of good and evil coexist with calculations of time-travel and infinity as expressed through mathematics and physics. The works in Lots of art forms in madness are also directly informed by Holding’s experiences of “madness” and homelessness throughout his life.

Entering Seventh, I’m faced with the two largest works in the exhibition, a pair of paintings approximately 100 x 150 cm in size. Both are studies of rural homesteads and introduce several of Holding’s recurring figurative motifs: the windmill, water tank, wire fence, seemingly empty dwelling, and an ambiguous bat-like flying creature. Of this creature, Bella Hone-Saunders—the current gallery director—informs me that in their conversations with Holding he was resolute in maintaining this ambiguity. Similarly, the time of day in these paintings is difficult to distinguish and can only be described as crepuscular, hovering in the half-light of dawn or dusk. This indeterminacy continues throughout Holding’s landscapes, as I will discover over the course of my visit and is largely achieved through colour. In these two paintings, the skies are muddied bands of cadmium orange, red, and light magenta, and in both a yellow disc hangs low on the horizon as what could be read equally as a sun or moon. The earth is rendered in blocks of pink and grey-lilac, and the buildings in yellowed siennas and red ochres, each contained within black outlines. The overall effect is ominous and portends the works in the middle gallery.

Here I find paintings and drawings hung according to several subthemes: three domestic interiors, six floral studies, and six more rural scenes. Again, Holding’s use of colour suffuses these latter scenes with an uncanny tension, emphasised by the new presence of emaciated horses and dogs. In one particularly animated composition, chained dogs dance around what appears to be two hocks of ham, as the aforementioned flying creatures are suspended over an orange sky. Hone-Saunders mentions Holding’s interest in Australian painter Russell Drysdale, and I wonder whether another of the former’s dog works isn’t a homage to the latter’s Man feeding his dogs (1941). In that work and Holding’s exhibited here, a man strides across a reddened landscape to feed three similarly chained dogs. This influence holds more generally too, as Holding’s darkened skies recall those of Drysdale—particularly as seen in paintings such as Walls of China(1945), Crucifixion (1946), or Sofala (1947)—where brown-red skies loom over what was imagined to be a desolate landscape.

A brief exhibition text gives some context to this imagery:

A pivotal moment in (Holding’s) life occurred when he was first admitted to a psychiatric ward. It was ten days before his 17th birthday. He was homeless and picked up by services at half past five in the morning. Much of his perception of houses and landscapes reflects this time and his sense of an empty uncaring society. He describes the years following this as “running through the system without shoes.”

The foreboding tone of Holding’s rural landscapes resonates through this biographical detail, as does the strange quality of the light. I turn to the interior scenes with this in mind. In each of these works on paper, a room is rendered in careful two or three-point perspective, emphasised by floorboards painted blue, yellow, or red. This primary palette is used throughout all three paintings—blocking out tables, walls, windows, and doors. In one room a scrawny cat and slightly healthier-looking rodent share a meal on the floor, and in others there are tables laid with food, drink, and flowers. Holding has described these vignettes as views into houses from the period in which he was homeless. Certainly, the bright, flat light of the rooms—each illuminated by spiky blue rays emanating from a central lightbulb—recalls the effect of walking past houses at night, the contents of their interiors visible in stark detail. Consistent with Holding’s description, the edges of the painting become a window frame, and position the viewer as peering into the room from outside, rather than being inside it.

In the third and largest space at Seventh are Holding’s studies of Hobsons Bay as seen from Williamstown on Bunurong Country. With a thin black line, Holding has traced boats with their rigging, the pier and various buoys bobbing amongst it all. Small, well-defined clouds echo the recurrent ambiguous flying creatures, with elongated appendages that resemble wings. I suspect I could currently be modernism-pilled—having just finished tutoring an undergraduate modernist avant-garde art history unit—but for me, Holding’s overarching concern with shifting atmospheric light conditions is decidedly impressionistic. For example, though Holding’s brushwork is comparatively flat, the return to these bayside scenes through dramatic colour shifts alludes to both Claude Monet’s “Charing Cross Bridge” and “Le Grand Canal” series. Over several renditions of Hobsons Bay, skies and water shift from lilac and peach to cobalt blue and orange, to dark red and black.

In one of these renditions, I initially read flames shooting from the light posts set along the pier—but Hone-Saunders suggests this could be Holding’s representation of the electric street lights. I think back to the spiky blue rays of the lightbulbs in Holding’s interior scenes and am inclined to agree. Modernism-pilled again, I’m now given to think of Giacomo Balla’s painting The Street Light (c. 1910), where small, overlapping chevrons of colour explode outwards from a glowing central lightbulb, in a pointillist-like expression of additive (light) colour-mixing. In both Balla and Holding’s paintings, the illumination of the electric bulb manifests as dynamic, zig-zagging matter. Perhaps this foregrounding of light—as natural or artificial, exterior or interior, and producing drastic shifts in the colours of a landscape—can be understood as a through-line in Lots of art forms in madness, linking the representational scenes with Holding’s concern with the physics of space and time. Indulging my Impressionist connection once again, the characteristic preoccupation of the movement with both atmospheric light conditions and additive colour theory was itself informed by contemporary experiments in optical science and the physics of light. Holding’s engagement with these disciplines is noted explicitly in the exhibition text and in the inclusion of mathematical symbols and equations throughout many of his drawings.

This turn away from Holding’s landscapes is marked by a large table in the same room, covered with at least twelve black presentation folios. Ranging in size from A4 to A2, the folios contain what I am sure are hundreds of works, arranged according to Holding’s own cataloguing system. As I make my way through each folio, I encounter images of flowers, landscapes, empty streets, homesteads, and more waterfront scenes—though most striking and numerous are the pages and pages of geometric abstractions that form the majority of this vast collection of works on paper.

Rather than a purely formal study of these shapes—circles, ovals, dots, squares, lines, hearts, triangles, and so on—these works are examples of Holding’s sophisticated personal lexicon of symbols that overlaps with and extends that of contemporary mathematics and physics. I’m not sure whether Holding is self-taught or has formal training in the field, but throughout the drawings—which span the past twelve years—he has folded equations pertaining to infinity, energy, and space into the works. Many employ an all-over composition, where symbols are drawn or painted in innumerable combinations on cartridge or canvas paper. In others, recognisable objects make an appearance—guitars, vases, bottles, animals, and skulls recur—as well as the occasional phrase (“study the body,” “now -> tomorrow,” “I ♡ U,” “I love people”). In a particularly complex work from 2009, Holding has laid out a “time machine” system like a circuit board diagram, which includes the dimensions of “future” and “past” but also “evil / good” and an “honesty / bias drive.” This diagram sits against a background of undulating blue stream-like shapes, red blobs, and yellow circles. Due to my mathematical incompetence and the personal nature of Holding’s system, I make no attempt at deciphering any of these equations—but I also don’t think this is the point. Rather, my sense is that Holding’s drawings function both aesthetically—as I appreciate them—and as a working-through and expression of his own line of enquiry into transcendent planes of thought.

Joan Miró is cited as another influence of Holding’s, and I think particularly of Miró’s “Constellation” series, created between 1936 and 1941 while the artist was seeking refuge in France from the Spanish Civil War and Second World War. Through these twenty-four paintings on paper, Miró innovated a language of geometric motifs—both representational, such as eyes or stars, and abstracted shapes. Further, Miró wrote that the process of making the work assisted in diminishing the anguish he was experiencing. Though each element in Miró’s lexicon contained a discrete meaning for himself, some of which was perhaps decipherable to others, the enduring significance of the work is not in its complete readability, but in the attempt to develop a personal system of expressive signs. I would argue that this is also the case with Holding’s presentation here.

Alongside this shared methodology, it could be argued that both Miró and Holding demonstrate an express interest in “madness” as a generative state for art making—the former through his connection with the Surrealists, whose interest in the artwork of “mad” people could now be considered at once exploitative and celebratory, and the latter through a more first-person embodied standpoint as someone who has experienced mental illness and social disruption, and who, as a result, is interested in how art can explore various states of “madness.”

Walking back through Seventh towards the front door, I return to several paintings I had previously not quite known how to comprehend, installed between the first and second rooms. Here, four portraits are arranged around text painted directly onto the wall, reading “Portraits of men similar to me…” Though I don’t know what Holding looks like, I imagine a composite of each white-bearded face before me. Indeed, Lots of art forms in madness could be understood to be one large composite portrait of Holding, a generous presentation of his subjective experiences, both “running through the system without shoes” and developing his own system of signification and belief. Despite not being completely privy to the inner workings of this system, Holding’s dedication to the project and its varied modes of expression is intensely compelling, and I left the exhibition feeling wholly energised by this conviction.

Amy May Stuart is an artist living in Naarm.