Linger, Dash, Talk

June Miskell

On the weekend that I visited Linger, Dash, Talk (2023) I found myself in states akin to the exhibition’s title. I lingered, talked—but mostly “dashed,” if I’m honest—as I celebrated the sweaty, joyous, and quite frankly overwhelming three-weekend long party that was Sydney WorldPride, or “WP” as a friend referred to it. In the constant dash from one event or exhibition or program to another, it became clear to me that with the WP event-frenzy came an unprecedented level of queer representation and visibility.

Greater public visibility can be empowering and celebratory, but it is a double-edged sword, still too often obscuring undertows of anti-LGBTQIA+ violence, erasure, and censorship. As this review goes live, LGBTQIA+ activists are counter-protesting the latest in a string of growing far-right rallies and actions that saw the vandalisation of queer murals during WP and religious groups marching through Newtown. As Filipinx artist Bhenji Ra cautioned in a tweet in 2021, “What is visibility without protection? A trap.”

In recent years, the complicated politics of visibility, or as Verónica Tello says “hyper-visibility,” of queer artists has led to a variety of strategies, not least retreating into an aesthetics of coded and evasive works, as was the case with EO Gill’s Screwball (2022). Linger, Dash, Talk, co-curated by Jackie De Lacy and Dennis Golding, takes on a similar approach to Screwball. As De Lacy and Golding argue, the artists they included are interested in “encoded, private or anecdotal languages as tools of redress.” For example, the language of slang (which is used in the show) is not always “legible to or understood by dominant positions.” It allows dialogues “to remain a secret, creating intimacy in moments of non-disclosure or shared understanding,” the curators tell us.

The emphasis on non-disclosure that pervades Linger, Dash, Talk also resonates with Pari’s current exhibition Reading into Things (2023). In their review of this exhibition, Memoer Audrey Pfister speaks of abstraction “as an alternative to the politics and demands of representational visibility.” Such an abstraction, Pfister continues, “aims to resist easy legibility in a world that constantly demands it (often for tokenistic box ticking). Abstraction works to remind us that queerness is not one thing.” Like the Pari show, Linger, Dash, Talk carefully negotiates this tension between abstraction and visibility, particularly as it plays out in language.

The acts of reading, re-reading, and reading between the lines are key to Linger, Dash, Talk. The first work I encountered when visiting the show was Troy-Anthony Baylis’s Immediacy Paintings (2019-22), comprised of fourteen small monochromatic paintings. On them are whip-smart vernacular phrases like: you want a Maserati? You better workbench (2022), or a shopping of gays and a serious of lesbians meet at the gallery store (2022), and Sologamy? I barely know me (2022). Clustered together (but also making additional appearances wedged between other works throughout the exhibition), Baylis’s pop-cultural references and slogan-like phrases are difficult to grasp from afar—much of the text only becomes readable upon closer inspection.

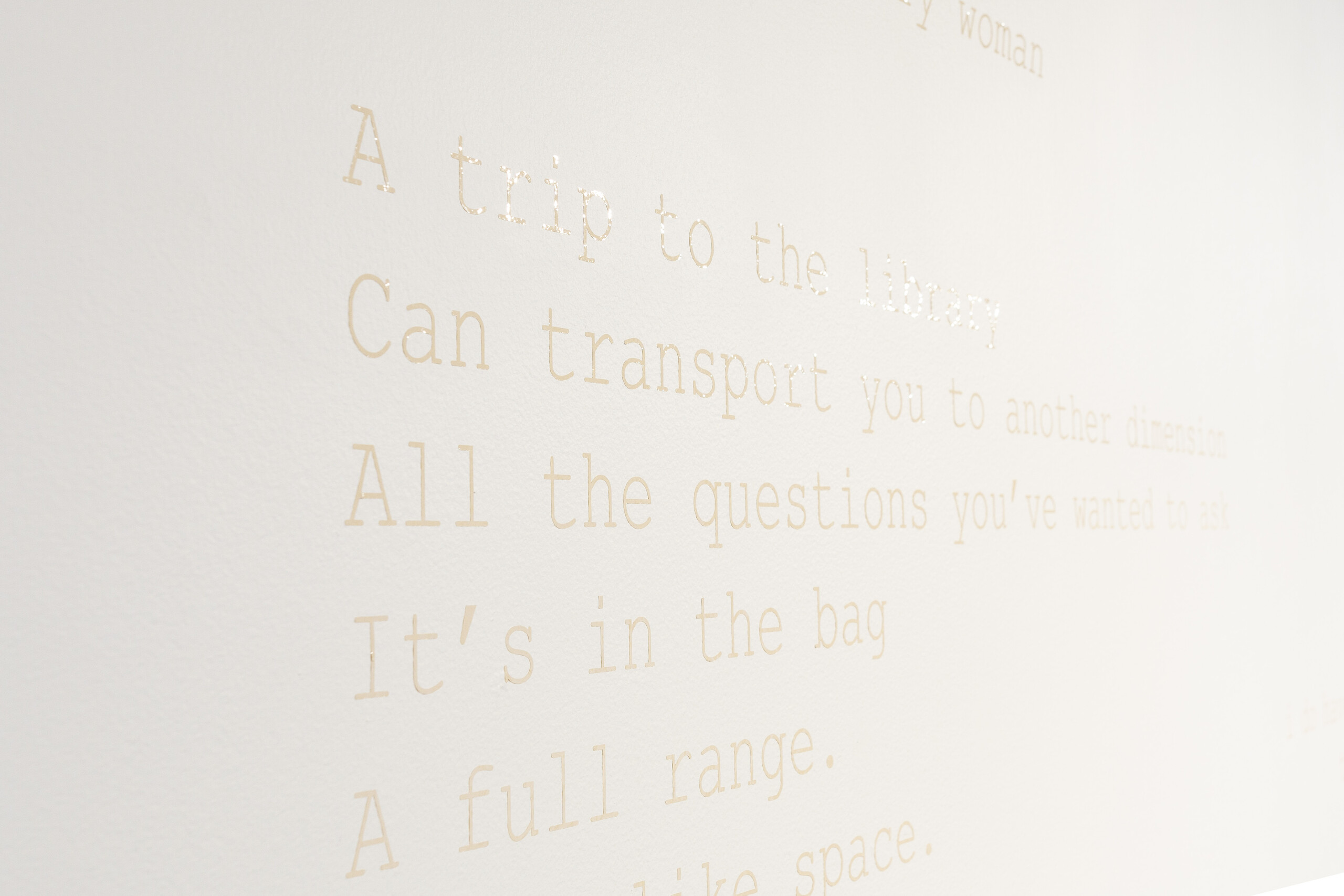

Like Baylis, but perhaps more explicitly, Ellen Van Neerven employs a tactic of evasion that mediates easy legibility. Skirting the adjacent walls are two poems by Van Neerven from their book Throat (2020). Installed in cream-coloured vinyl, the deeply personal and evocative poems Library (2020) and Bonsoy (2020) almost disappear into the white walls, only coming into intermittent clarity as you move your body back and forth through the space. These works evoke what Jack Halberstam refers to as “modes of transmission that revel in the detours, twists, and turns through knowing and confusion, and that seek not to explain but to involve.” As one lingers and readjusts one’s body in relation to these works, what unravels is a deeply autobiographical and intimate use of language that plays with the visibility of the everyday via throw-away phrases and highly personal cogitations (not dissimilar to Baylis). To be involved then, suggests being in relation with, which operates differently to modes of engagement elicited through representation that engender being looked at, classified, or consumed.

If the visibility of the queer body was for a long time the province of the hard and social sciences—and its language of “deviants,” “criminals,” “outliers,” etc—then nearby works by Benjy Russell, Jenna Lee and Mackenzie Lee interrogate and re-read these histories. The back wall is covered by two large vinyl wallpapers, Come to my window (2018) and Clutch’s hormones and Benjy’s HIV meds on a mirror (2016), designed by Russell in collaboration with their friend, and writer, T Fleischmann. The works spell out phrases such as “object-orientation” and “post-scarcity” with multihued dyed clothes in the former, and the artists’ HIV and HRT medicines in the latter. I began reading Fleischmann’s book Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through (2019) prior to visiting the exhibition and it felt serendipitous to arrive at a point in the book where they reflect on this work. They note that “categorization isn’t how we acknowledge difference, but rather its enforcement, difference leveraged to keep things apart that could well be together.” Brought together, these works suggest the presence of multiple bodies without representing them, instead indexing their somatics, chemicals, and politics via textual and material arrangements.

Similarly, the strategy of indexing the body is at play in Jenna Lee’s Self: Adorned #1, #2, #3, #4 (2021) and Mackenzie Lee’s *Adornment*, Obscurement (2021), Blood Type: Ink (2021) and Epidermis Verso (2021). Hanging in the gallery’s alcove, these works reconstitute pages from so-called “Aboriginal Word Dictionaries” into woven adorned objects of display for Jenna’s Self: Adorned series and hand-made paper for Mackenzie’s poems. The text within Jenna’s woven adornments is made intentionally difficult to discern and prompts us to consider settler-colonial methods of taxonomy and categorisation. The work is reminiscent of colonial modes of museological display (the adornments are framed and secured by pins) though what is intentionally left incomplete are the identification labels which remain blank, suggesting that the identity of the wearer cannot be classified and must be self-determined. This is further embodied throughout Mackenzie’s poems which punctuate the same wall, vulnerably revealing the oft-lingering processes of negotiation in constructing one’s identity and rendering it visible to the world.

Across Russell’s and the Lee’s artworks is a re-reading of racialised, gendered, and sexualised systems of classification and categorisation—legacies that share roots in colonial and imperial taxonomy. This has a twofold effect when being read in the context of WP. On the one hand, there is a clear negotiation of these systems and legacies that re-assert control over one’s self-identification and visibility. On the other hand, this prompts us to reconsider the heightened public queer visibility of WP and Mardi Gras in Australia that predominantly centres white gay and lesbian histories.

What unites the artists in Linger, Dash, Talk is that they are all queer identifying First Nations artists who (as the curators articulate) revel in “staunch moments of non-disclosure.” To hold such a staunch position that withholds and refuses dominant modes of queer kinship rather than one which succumbs to the demands of WP—which privileges white bodies and histories—aligns Linger, Dash, Talk with self-determined moves by queer identifying First Nations artists in Australia (also seen in other WP exhibitions like Marri, Madung, Butbut at Carriageworks, Baya, Ngara, Banga (Speak, Listen, Make) at Boomalli Gallery, Karla Dickens: Embracing Shadows at Campbelltown Arts Centre and Dylan Mooney: Still Here and Thriving at N.Smith Gallery).

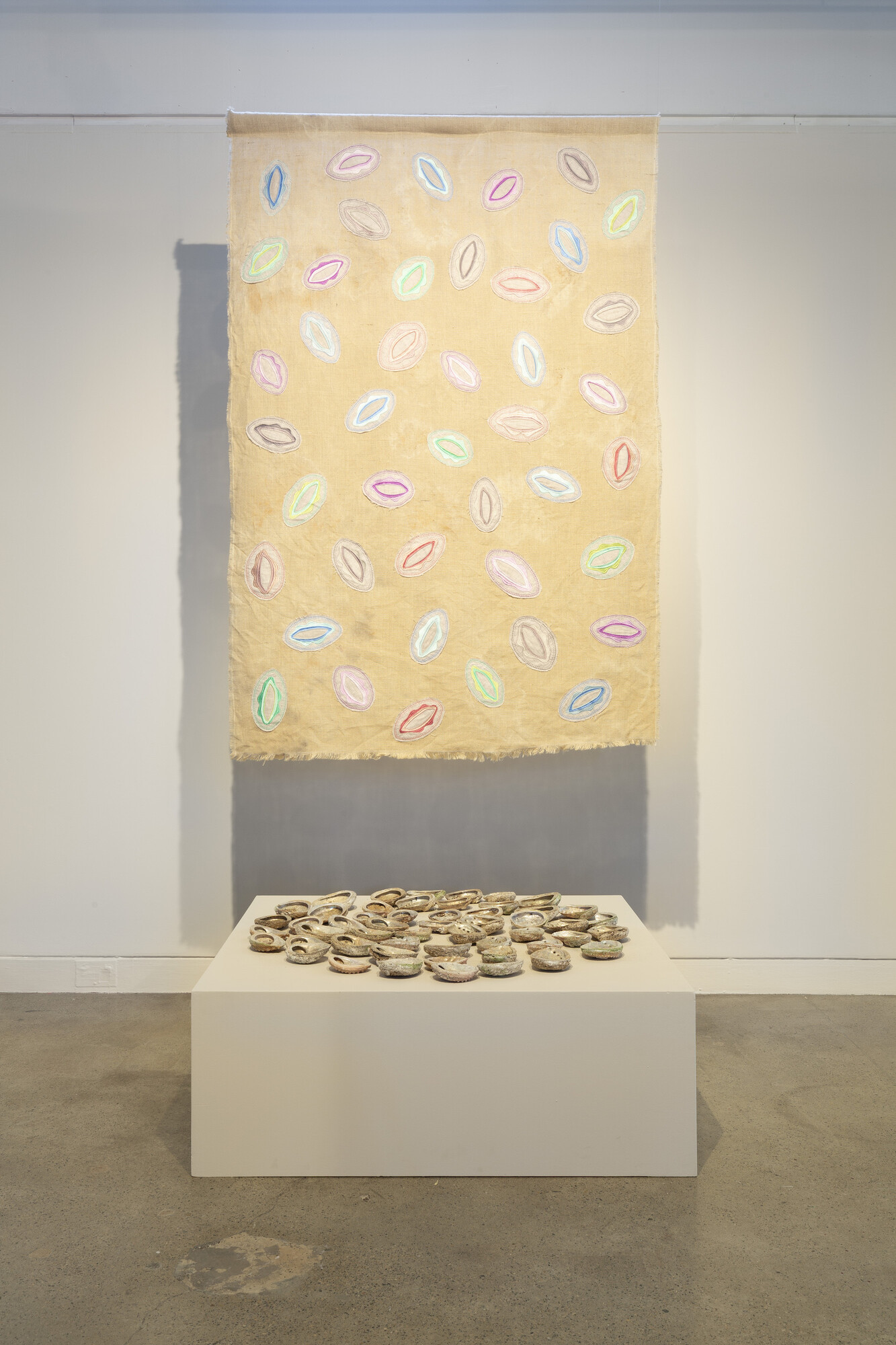

Staking a claim for visibility via the sacred knowledge of land and familial connections are works by Kirli Saunders and Sereima Adimate in collaboration with Kiki Oner and Garden Reflexxx. Greedy (2023) is an audio and mixed media installation by Saunders. The work consists of a tapestry made in collaboration with Millie Hall depicting iridescently stitched abalone, hand-collected abalone shells which rest on a plinth below, and a poem recorded by Saunders. In the poem that loops softly above, Saunders addresses the capitalist and colonial consumption of Country through the overfishing of abalones which “modify reefs with colonisation, causing baron ground, so proud Aunties can’t hand down this Saltwater Women wisdom.” As the exhibition room sheet notes, the stitched abalone sketches were derived “after cleaning and cooking abalone with her Aunties on Yuin Country.” Casting a gentle shadow on the wall behind it, the abalone illuminated by Saunders honours the continuation of and connection to cultural knowledge, while also making present the matriarchal relations that protect it.

Similarly, Adimate’s multi-channel video installation Mood Ring (2023) foregrounds the journey of reconnection with heritage and being guided by ancestral intuition.Housed in the gallery’s upstairs mezzanine, which is painted an oceanic blue, Mood Ring is a video poem based in/on Fiji and is comprised of several small screens hung at varying heights which lead toward one larger screen. Each of the smaller screens plays short clips—cars traveling along a tropical road, a sunset reflected over water, Adimate sliding into a pool—all of which loop momentarily. As noted in the accompanying statement by Adimate, Mood Ring tracks an intuitive journey of “connecting the dots” between Adimate’s and their collaborator Chiara/Kiki Oner’s family ancestry. For Adimate, this journey meant “going back, unsettling the land and putting together a jigsaw puzzle made up of dreams, hallucinations, and whatnot.” In one particular scene, Adimate, Oner and Adimate’s Bubu Vani sit in dialogue with one another on the steps of the abandoned cultural center in Pacific Harbour, Fiji. For the most part, it is difficult to hear what they are saying as the volume remains low and their conversation is kept private. Watching from a distance, Mood Ring remains only partially revealed—only being visible in snippets or mediated by a non-linearity and low volume that keeps what is sacred private.

Staunch, intimate, and mediated moments of exchange, identification, and reconnection structure Linger, Dash, Talk. Like Screwball, this exhibition is comprised of a series of intimate networks—dialoguing in the coded and anecdotal ways that friends do. What is different about this show compared to many other shows programmed in WP and a show like Reading Into Things (which shares a refusal of easy legibility) is that it all the works exhibited are by queer First Nations artists.

As the queer Australian art research collective KINK note in a recent article: “the visibility and interpretation of queer experience is always in question, always needing to be read against the grain of the framing devices that seek to regulate and disguise its productions, meaning, and reception.” What does legibility, visibility, and representation mean for queer First Nations artists? Against the backdrop of WP and queer culture/history more broadly, Linger, Dash, Talk tells us that the terms of visibility—and who can determine its conditions—matter, more than visibility itself. Not being visible is itself a potent way of critiquing and undoing the systems upon which our histories and bodies can be on display. It’s therefore little surprise that we are seeing the simultaneous rise of both hyper-visibility and abstraction as key aesthetic tropes in, for lack of a better term, “contemporary queer aesthetics” in Australia. Is it a coincidence that the strongest shows that have emerged out of such an aesthetic lean into abstraction?

June Miskell is a writer, editor, and researcher living on unceded Gadigal and Wangal land. She teaches at UNSW Art & Design, Sydney where she is currently undertaking her PhD.