Khaled Sabsabi: A Hope

Anastasia Murney

A Hope is the second chapter in a comprehensive survey of Khaled Sabsabi’s multidisciplinary artistic career. The first chapter, A Promise, was exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2020, curated by Matt Cox in close collaboration with Sabsabi. A Hope is on at Campbelltown Arts Centre until 27 March and is curated again by Sabsabi, Cox and Adam Porter. It is the larger of the two exhibitions, offering up eighteen artworks across six distinct spaces. This generous use of the galleries at Campbelltown Arts Centre strives to accommodate Sabsabi’s expansive thinking. His work moves across multiple scales, gesturing to transcendental spiritual heights and sifting through the quotidian aspects of individual and collective life. The exhibition is, at times, overwhelming, staging a lot of large-scale, ambitious projects that deal in complex spiritual and metaphysical ideas. But it also offers moments of quiet reflection and pleasurable symmetries.

To engage with Sabsabi’s work is to become better acquainted with Sufism (Tasawwuf is the proper Arabic term), a mystical-philosophical tradition that runs through Islam. There is a range of Sufi orders that connect to other religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, a multi-faith disposition that Sabsabi explores in his work. One of the core commitments of Sufism is the pursuit of nearness to the infinite or, in other words, the Divine (Allah). For Sabsabi, this means experimenting with aesthetic languages that eschew standard modes of perception. Much of his artistic engagement with Sufism is entangled with his personal experiences. The Sufi practice of Dhikr, referring to the recitation of divine verses, calls to mind Sabsabi’s earlier life as a hip hop artist, forming the crew Count on Damage (COD) in Western Sydney during the 1980s. He and his family escaped the Lebanese Civil War and migrated to Western Sydney in 1978, where he continues to live and work. Both A Hope and A Promise are testament to Sabsabi’s rich artistic career, working across painting, video, sound and installation. Over the last four decades he has been a devoted advocate of Western Sydney and its culturally diverse populations, contributing to a range of social and artistic infrastructures.

Sabsabi offers two similar sounding definitions for “promise” and “hope” to guide each exhibition. Both reflect on how to craft a better future and cultivate trust and shared understanding. But where a promise is “an assurance that is enlivened by an action”, a hope is “an offering of the in-between space—-the slow and unseen space”. A Promise was quite a lean exhibition, highlighting works that were more agile, vivid and sharp-edged. A Hope, however, unfurls at a slower pace. The exhibition itself is murkier and more introspective, as if peeling back some of the dense layers of A Promise and reorganising them into a softer shape.

The entry point into A Hope mirrors that of A Promise. Both demonstrate Sabsabi’s keen interest in memories rippling through time, refusing to sit still. In the AGNSW exhibition 70,000 Veils (2004–14) thrust the viewer into Sabsabi’s midcareer practice. It is a ninety-six-channel video installation, giving intricate expression to a teaching from the prophet Muhammad: “there are seventy thousand veils of light and darkness between the individual and the Divine”. Sabsabi deconstructed and recomposed ten thousand photographs, fragments of everyday life taken over a period of ten years. The work pulled together a composite of memories, separated into abstract layers of technicolour blue and green (to be glimpsed through 3D glasses). It was also a multisensory work, emitting heat, vibrations and a subtle scent of rosewater.

At Campbelltown Arts Centre the first work to greet the viewer is Aajnya (1998/2020). A reproduction of Sabsabi’s first ever installation, this opening suggests a more linear approach to Sabsabi’s artistic career. A rope of shimmering copper is fixed to the ceiling, unravelling into individual wires which connect to small speakers, arranged on the ground into a neat grid. This is framed by a large panel splashed with coffee drip marks, another sensory trigger. But instead of coalescing multiple memories (as in 70,000 Veils), Aajnya focuses on just one. It represents a traumatic childhood experience where Sabsabi was forced to seek refuge in a basement from bombing during the Lebanese Civil War. From a distance, the copper starts to resemble flooding water, perhaps from a burst pipe above, while the ominous drone of the speakers—-near inaudible in this installation—-underscores the encroaching threat of war. The simplicity of materials contrasts with the luminous digital manipulation of 70,000 Veils. On the one hand, Aajnya is a reminder of Sabsabi’s longstanding commitment to working at a more intimate scale, disrupting the familiar image of his practice as centred on large-scale video installations. On the other hand, both works offer frames for understanding Sabsabi’s practice and its orienting/disorienting relationship to the punctum of time, understood as both point of origin and endpoint.

There are a few points throughout A Hope where Sabsabi’s investigations into internal spiritual experience crystallise into collective and embodied rituals. These works are anchors that balance some of Sabsabi’s more sweeping gestures towards “universal communities”. The riotous noise coming from Wonderland (2014), eclipsing that of Aajnya in the next room, features a crowd of chanting Western Sydney Wanderers supporters, otherwise known as the Red and Black Bloc (RBB). A related work, Organised Confusion (2014), featured at the end of the exhibition at AGNSW. The machismo of these works can feel claustrophobic, especially in A Hope, where the experience of weaving between the two screens intensifies the atmosphere of football fanaticism. For Sabsabi, however, these works are defiant celebrations of multicultural togetherness. The rhythmic practice of Dhikr is central here. The beating of the drum and synchronised chanting is meant to facilitate an ecstatic spiritual experience, where the individual dissolves into the collective.

In Bring the Silence (2018) four tilted screens are suspended above an overlapping arrangement of colourful woven rugs. The fifth screen, in the centre of the space, is positioned as a tabletop. To wander over to this screen and peer down from above feels voyeuristic. Similarly, to step onto the rug feels like crossing a physical threshold. The work depicts worshippers attending sacred burial sites, known as Maqam in Arabic. The Maqam in this work is the tomb of Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya, one of India’s most famous Sufis. The close crop of the space inside the Maqam, which only men can enter, is dense with flower petals and endless prayer, although Sabsabi breaks this protocol to open the space to all viewers. Another privileged insight into ritual is Naqshbandi Greenacre Engagement (2011), which won Sabsabi The Blake Prize. This work reveals the weekly gatherings of the Greenacre Order, a few families that come together to practice their faith in a nondescript scout hall. It is a humble installation—-three monitors on the ground, tucked into a corner near the tail-end of the exhibition. Perhaps for this reason, it is difficult to give the work the close attention it deserves. In any case, these three works provide the sonic pulse of A Hope: the viewer is never quite out of earshot of the soft and loud chanting that loops them together.

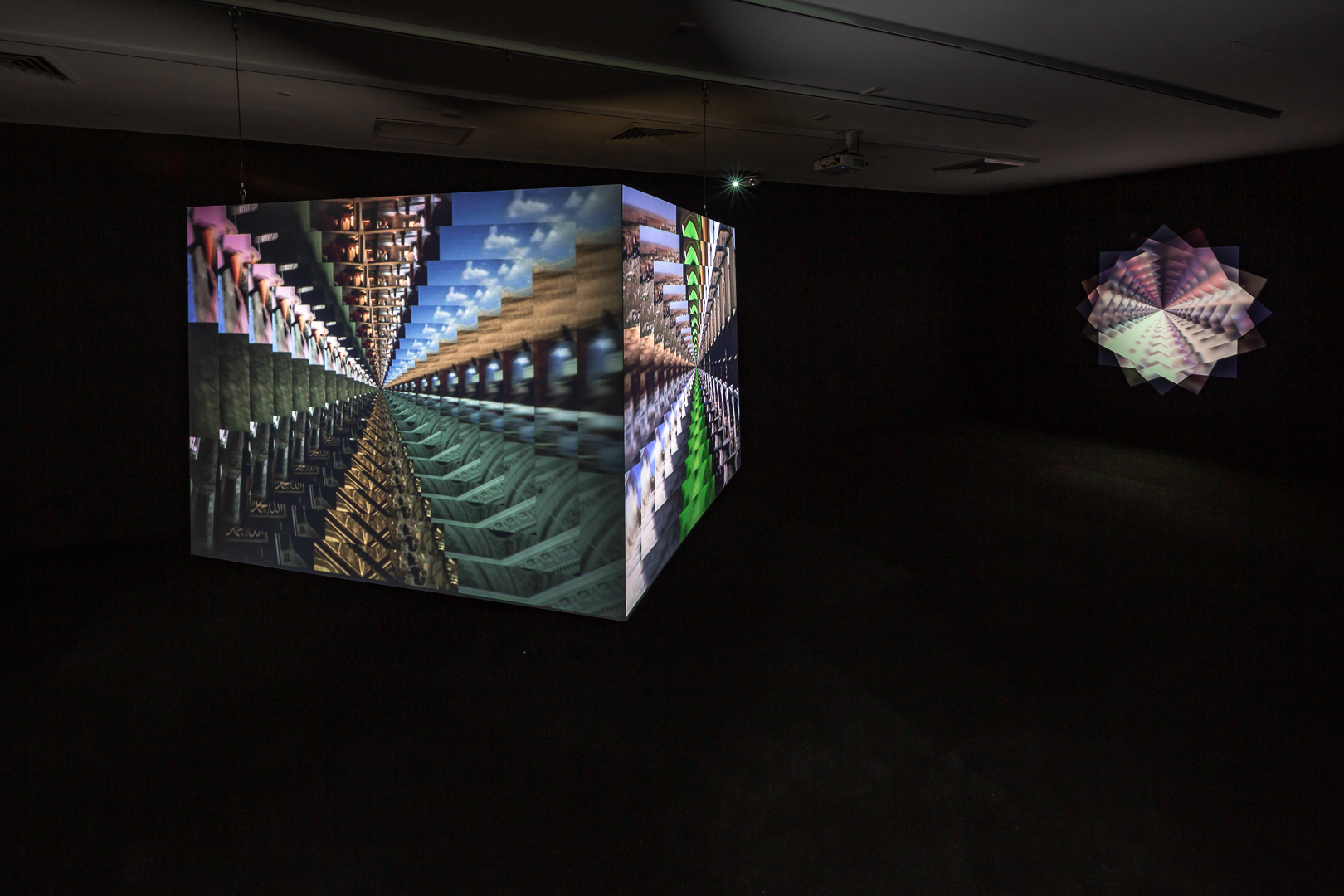

Sabsabi’s Mush (2012) is one of the most magnetic works in A Hope. It seems to perform a similar function to 70,000 Veils in A Promise, stitching together different temporalities and geographies. Leaving the freneticism of Wonderland behind and stepping into the digital glow of Mush feels like a satisfying dramatic transition, as if the sweating bodies are evaporating into cosmic space. Mush is a levitating cube, an “illusion of infinite”, in Sabsabi’s words. As with 70,000 Veils, Sabsabi created this work by collecting images from his travels across the Middle East and North Africa, translating them into a geometric kaleidoscope. The title “mush” refers to the mixing and sharing of food. As Sabsabi insists, this is not to homogenise cultural differences but rather to rearticulate them on a higher metaphysical plane. To walk around the cube is akin to the ritualistic circling of The Kaaba in Mecca. As the multi-layered image shifts clockwise and counter-clockwise, there is a central vanishing point—-the promise of total enlightenment in perpetual recession. Mush rehearses one of the recurrent tendencies of Sabsabi’s practice, which is about negotiating access to the Divine. A spiritual cartographer, he is often testing new perspectives and representational strategies, tilting the map to reveal a new path.

The middle section of A Hope stages some of Sabsabi’s newest works alongside some of his oldest. 40 (2020) comprises several paintings and two video installations. In this work he draws together the numerical and the spiritual to highlight the multi-faith significance of the number 40: Jesus fasted for 40 days and 40 nights in the Judean desert, Muhammad was 40 when he was first visited by the archangel Gabriel, Hindu prayers consist of 40 shlokas or dohas. Bracketing the exhibition space, the two video installations show a slow and mesmerising loop of ethereal images: three hooded figures turn into three blood moons; then the surface of one moon turns to liquid as a pair of hands cuts the surface. The acrylic paintings depict the glowing white outlines of figures; the flat, monochromatic composition is reminiscent of Picasso’s Guernica. These figures are just visible through various grids and geometric patterns. There are also dozens of smaller paintings in 40 as well as in the next room, featuring A Self-Portrait (2004—14) and 5^th^ Pillar (2020). It’s quite a lot to process and can be difficult to discern some of the more intricate aesthetic details in these dimly lit spaces. Nonetheless, to spend considerable time in the heart of the exhibition is to ponder the strange perfection of the grid as a spiritual and aesthetic logic. Again and again Sabsabi navigates the dialectical relationship between the infinite and the finite: the limitations of the “real” world and the boundlessness of unseen spiritual realms. It’s interesting to see 40 alongside Sabsabi’s earlier video works from the early 2000s, on view in an adjacent space, which are short and sharp, almost like satirical little punches, often focusing on a single image or event, such as a bombed out apartment building, a 9/11 montage, barbed wire flickering against blue sky. These flashes of conflict and geopolitical tension sit in contrast to his later works—-an explicit political language that appears to soften over time, becoming rearticulated within the expansive context of Sufism.

At the Speed of Light (2016) is the cosmological endpoint of A Hope. Eleven screens are arranged in the middle of the room like an unfurling flower, all emitting bright white light. This is Sabsabi proposing the big question: “if we are able to travel at the speed of light, will we be able to enter and interact with unseen realms?” For this work, he recorded 218 hours of footage and compressed it into a single second-long video to represent the speed of light. In a sense, At the Speed of Light folds together the temporalities of 70,000 Veils and Aajnya—-the piling up of hours and hours of footage is diluted into a singular flash. A life expressed in many overlapping memories or just one. Once again, Sabsabi materialises and rearranges time (and light) in pursuit of the Divine, a beautiful and impossible horizon of enlightenment. One of the things that is most striking about Sabsabi’s artistic practice is his method of making patterns that visualise a ceaseless search for points of congruence between different knowledge systems. These are multi-linear and multi-dimensional patterns that refuse to reduce social, political and spiritual phenomena into neat binaries or formulations.

Anastasia Murney lives and works as a writer and teacher on Gadigal land. She holds a PhD from the University of New South Wales.