Karrabing Film Collective: The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland

Giles Fielke

Entering KINGS Artist-Run on a Wednesday afternoon, I slink past a homeless woman asleep on the sidewalk. Her things are pushed against the front window of a fast-food shop that looks and smells like Subway but isn't. Moments before, I'd jumped off a packed tram at the Southern Cross stop at the top of Bourke Street after skipping one which was overfull at Elizabeth Street. During the day, Kings Street is bustling with office and construction workers, cleaners, businessmen and tourists. On my way into the city, I had read about the Andrews' government contractors and police forcefully moving in on traditional owners and protestors to begin cutting-down the sacred trees of the Djab Wurrung for a Western Highway extension just outside of Ararat. This week, The Economist's 'Intelligence Unit' announced that Melbourne is the second most liveable city in the world, losing to Vienna for the second year in a row after holding top spot for the previous seven years.

Upstairs, no less than four separate exhibitions are on show concurrently in the modest KINGS galleries. The wooden flooring mirrors the colonial-era rafters supporting the floor above. Alongside stretched-canvas paintings by Georgie North, a series of statuesque paintings by Zoe Jackson, and a collaborative installation by Jake Treacy and Walter Bukowski (Ophelia), the relatively recent addition to the gallery space, 'Black_Box', is showing a work in progress, The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland,by the Karrabing Film Collective. The layered and re-sampled drama that plays out on-screen, with opening titles and a credit sequence, mark it as a work of film. The division of labour, and the citation of funding bodies alongside the performers and crew, suggest a humble production that is nevertheless international in its scope. For example, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven is a major sponsor of this, the fifth film by Karrabing.

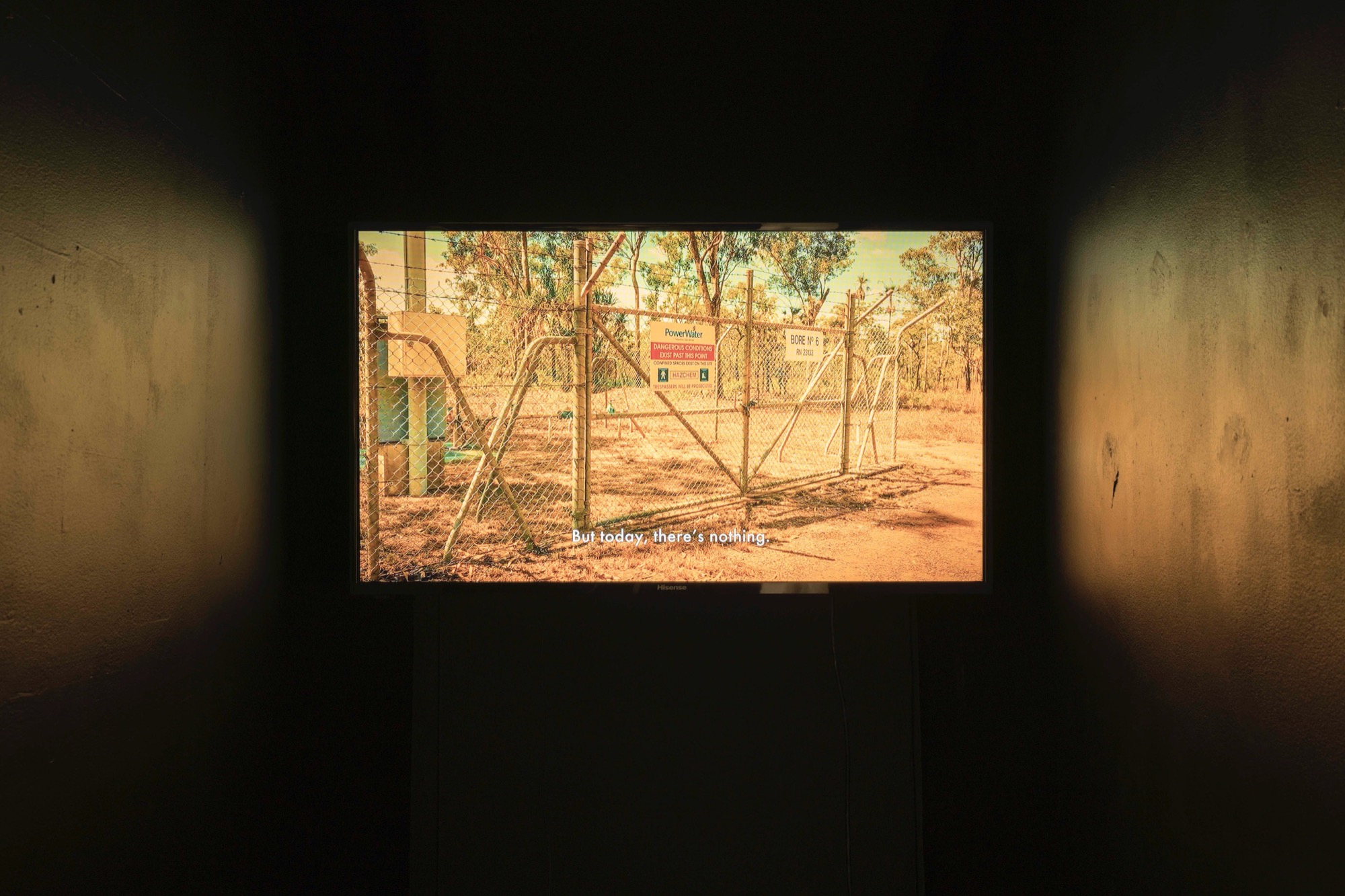

Initially curated by recess, Black_Box is a monthly video program that began at KINGS only this year and places the single screen in a darkened room, in direct contrast to the otherwise conventional white cube that codes the space as an art gallery. The present iteration of Black_Box was programmed in collaboration with Watch This Space, a contemporary experimental art space in Mparntwe/Alice Springs that was established in 1991. The screening in Melbourne has been planned to run in coordination with the Karrabing works currently on show there, under the title Day in the Life, which is the first presentation of Karrabing's work in Central Australia. Curated by Lisa Stefanoff, it may be that it is also the first exhibition of Karrabing's work in the Northern Territory.

The Mermaids seeks to intervene in contemporary discussions of the sources and solutions of contemporary climate change and toxicity.

Belyuen is a community of about 160 people in the Northern Territory and Karrabing includes a group whose 'lives interconnect all along the coastal waters immediately west of Darwin, and across Anson Bay, at the mouth of the Daly River'. This coast of the Northern Territory is in the Division of Lingiari (as is a large majority of the NT), for which the sitting MP, Warren Snowden, has served as federal member since the late 1980s. Karrabing includes about 30 members; it is an Indigenous Corporation, and promotes a form of filmmaking that its members describe as 'improvisational realism'. The auto-anthropology of the films first and foremost provides a sense of agency through self-representation. In that sense, Karrabing's work fits the current formation of much contemporary art: work that gestures to the existence of the artists who made it. From here the collective extends to include what they describe is 'a global transnational network of curators, artists, and filmmakers' too.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, the Franz Boas Professor of Anthropology and Gender Studies at Columbia University, New York, is a member of Karrabing. Povinelli has been instrumental for Belyuen since it was the subject of her PhD Thesis, 'The production of political, cultural and economic well-being at the Belyuen Aboriginal community, Northern Territory of Australia', which she completed at Yale in 1991. This is not to suggest the other members of Karrabing are not as important as Povinelli, but she is the exception, and perhaps a major reason why their films have premiered at the Berlinale, e-flux, Documenta 14, and the Centre Pompidou, since the film collective was established in 2013, following Karrabing! Low Tide Turning, a 14-minute film directed by Liza Johnson and Povinelli in 2012, and written and performed by members of the Karrabing Indigenous Corporation.

Another motivation for their turn to filmmaking was an attempt to force a different kind of conversation, which began in 2007, at a riot in Belyuen where members were 'threatened with chainsaws and pipes, watched as their cars and houses were torched, and their dogs beaten to death'. Following the Intervention the community felt like no one was listening to them. This is a strong theme throughout the films, especially The Mermaids: mistranslation, incommensurability, the technical distinctions between an inside and outside to a social body, the increasingly slim possibility of belonging to a legitimated community, which hinges on bodies of evidence that could be used in court proceedings for a long-standing claim to native title by the Larrakia.

Through marriage, ceremony, sweat you joinim but you also keep your roan roan strong. Det why people bin strong then. They bin respect that nuther person because they also bin connected like inside outside.

Karrabing member Linda Yarrowin states her point, and is then interpolated by Povinelli , who acts as a cultural mediator '(As so with marriage, ceremony, sweating in a place—by doing this you join the places that these activities cross over, but you also keep your own people and places strong. That is why people and places strong. That is why people were strong before white people came. They respected that other person because they were connected inside and had an outside)'. In the film two young people escape a medical facility, and struggle to understand their own country that initially appears alien, and then toxic, to their own ancestral memories of the place. It is full of characters who speak between dreamings like the Blow Fly, Pelican, and Mermaids, as well as the white fellas (played by black fellas) who don't understand the laws.

In the Emiyengal language karrabing means 'tide out'. But this is also a figure that carries cultural meaning. specific and general, to people dwelling in coastal communities everywhere. Language was first developed on the beach, according to an idea proposed by the writer and evolutionary anthropologist Elaine Morgan. Improvisation is a concept that is related to language in an abstract sense. It also carries meaning in the aesthetics of modernity, and in particular as a form of composition. Karrabing explicitly links cultural memory to the idea of composition in their artist statement. It makes me think of jazz, Cornelius Cardew's scratch orchestra and the aesthetics of chance. This may or may not be what Karrabing mean by improvisation. Their films do not, for example, feel jazzy. But they do have a certain looseness to the way the unusual narrative progresses. At one point, 'the mud place' becomes 'the end of the world?' and the insistence of the flicking / digging gesture seems to bring up deep-seated memories of a connection that is already in the process of being severed.

Similarly, realism seems to be a slippery term when applied to a form of playing against, rather than resisting, the extractive capitalism of successive Australian governments and in particular the mining interests impacting on the ancestral lands of the Karrabing community (i.e., everyone). Too-late-capitalism seems to be what is proposed here. Colonisation has already happened; life has been irreparably changed by the violence of an illegitimate usurpation of sovereignty. Further, historical signifiers that appear in discussions about Karrabing, like 'late-liberalism', moreover means liberalism had died, much like the late Bob Hawke, or Gough Whitlam, who poured sand into hands of Vincent Lingiari ten years after he led the Wave Hill walk-off.

Tess Lea has described Karrabing's films as 'residual artifacts' to their position as colonised subjects to an occupied country, and the films they have made so far—When the Dogs Talked (2014), Windjarrameru, The Stealing C*nts (2015), Wutharr: Saltwater Dreams (2016), Night Time Go (2017)—provide evidence that they are not interested in cinematic masterpieces or reproducing the ethnography of earlier-films like Two Laws (1981), which despite its ground-breaking approach to depicting Indigenous Australian sovereignty, sought to demonstrate what we already know: settler colonialism violated First Nations people and continues to do so. Instead, Karrabing experiments with media, reinventing themselves and their stories, even laughing at the fungible 'system' maintained and manipulated by those in power through their artwork. Rex Edmunds summarises the banality of this position when he was interviewed by Aodhan Madden about Karrabing: 'You got Indigenous ones, you got European ones. Some Europeans are good, some aren't, some Indigenous ones are good, some are not.'

In a recent New York Times article promoting the screening of work by Karrabing at MoMA PS1, the author somewhat ridiculously concludes that 'Indigenous Australians are the avant-garde of our species'. The column is titled 'Last Chance', reminding readers of the final dates of the series of Karrabing work currently on show there, and moreover that it is not to be missed. Of course, the fast pace of New York's cultural institutions and the contemporary art calendar couldn't be further away from the temporal complexities of Karrabing's filmmaking, and The Mermaids is threatened by its reification into cultural capital. For better or worse, 'Aiden through Wonderland' also manages to allegorise this strange destiny for a group of filmmakers and family from a tiny location that Google Maps tells me is only 28 hours away from Long Island, by plane.

Finally, Karrabing is most often received through its proximity to the documentary form emerging from ethnography as a colonial 'science' par excellence. Yet if anthropology is the discursive structure through which all of these works must be seen, it remains possible that we will remain stuck in the dialectic first recognised by Ousmane Sembène in 1965: 'You look at us as if we were insects,' he told French filmmaker and pioneer of visual anthropology, Jean Rouch. If we are to believe that Karrabing really are the avant-garde of our species, dehumanisation is the bitter truth we must all consider every time we look at the map. The answer is, of course, to protect this reality as the blow flies.

Giles is a writer and researcher. He is working on the Cantrills Collection at the University of Melbourne.