Kaijern Koo, glistening windows theory

Amy May Stuart

glistening windows theory (2020) is the first solo exhibition by recent Victorian College of the Arts graduate Kaijern Koo, presented at Daine Singer gallery’s new project space in Fitzroy. Sympathetic magic, as well as the “broken windows theory”, are mentioned by the gallery as reference points for Koo’s development of the work, and in keeping with the theme of nineteenth and twentieth century sociological theories, I have to add “conspicuous consumption” to the mix.

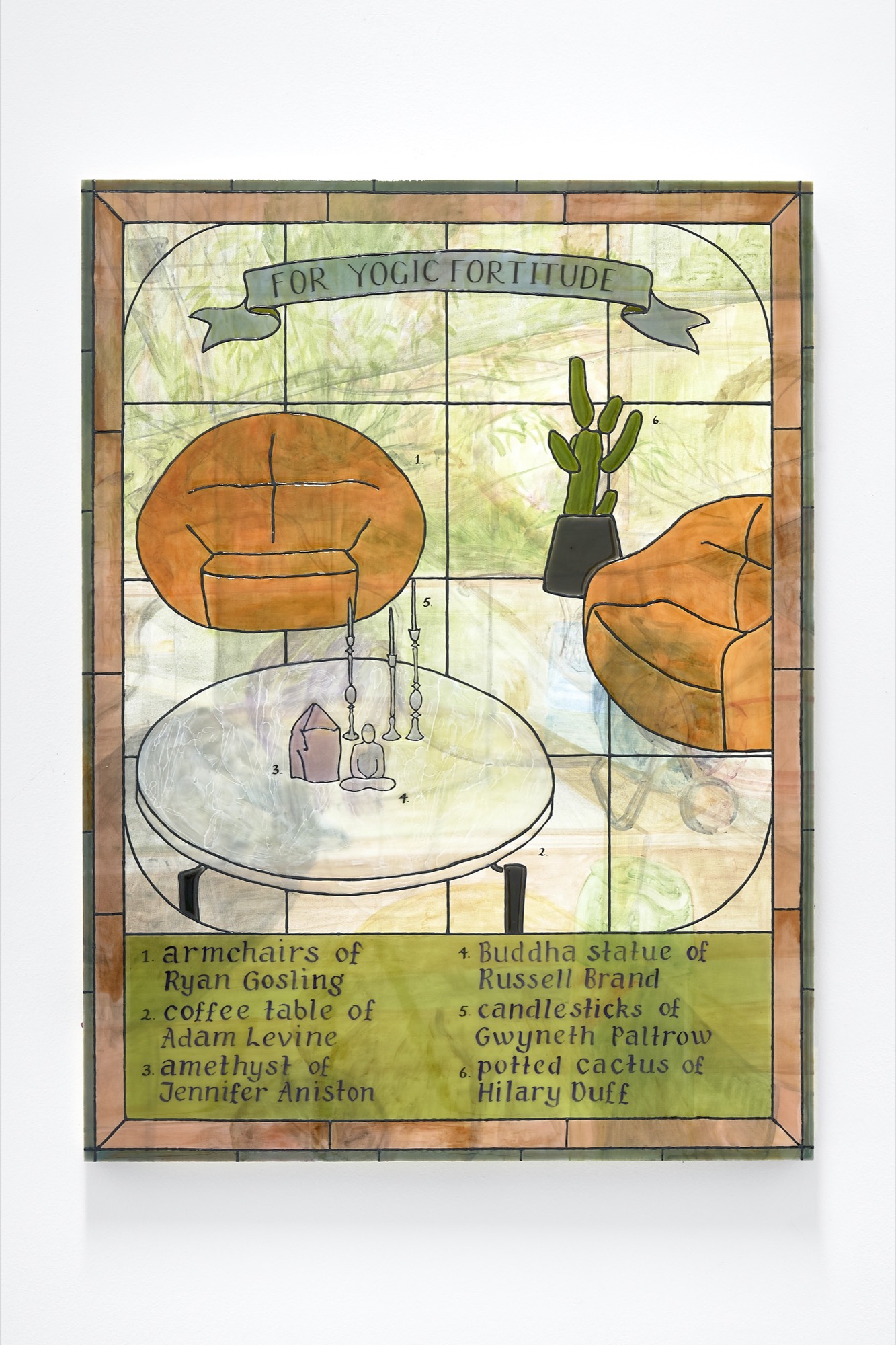

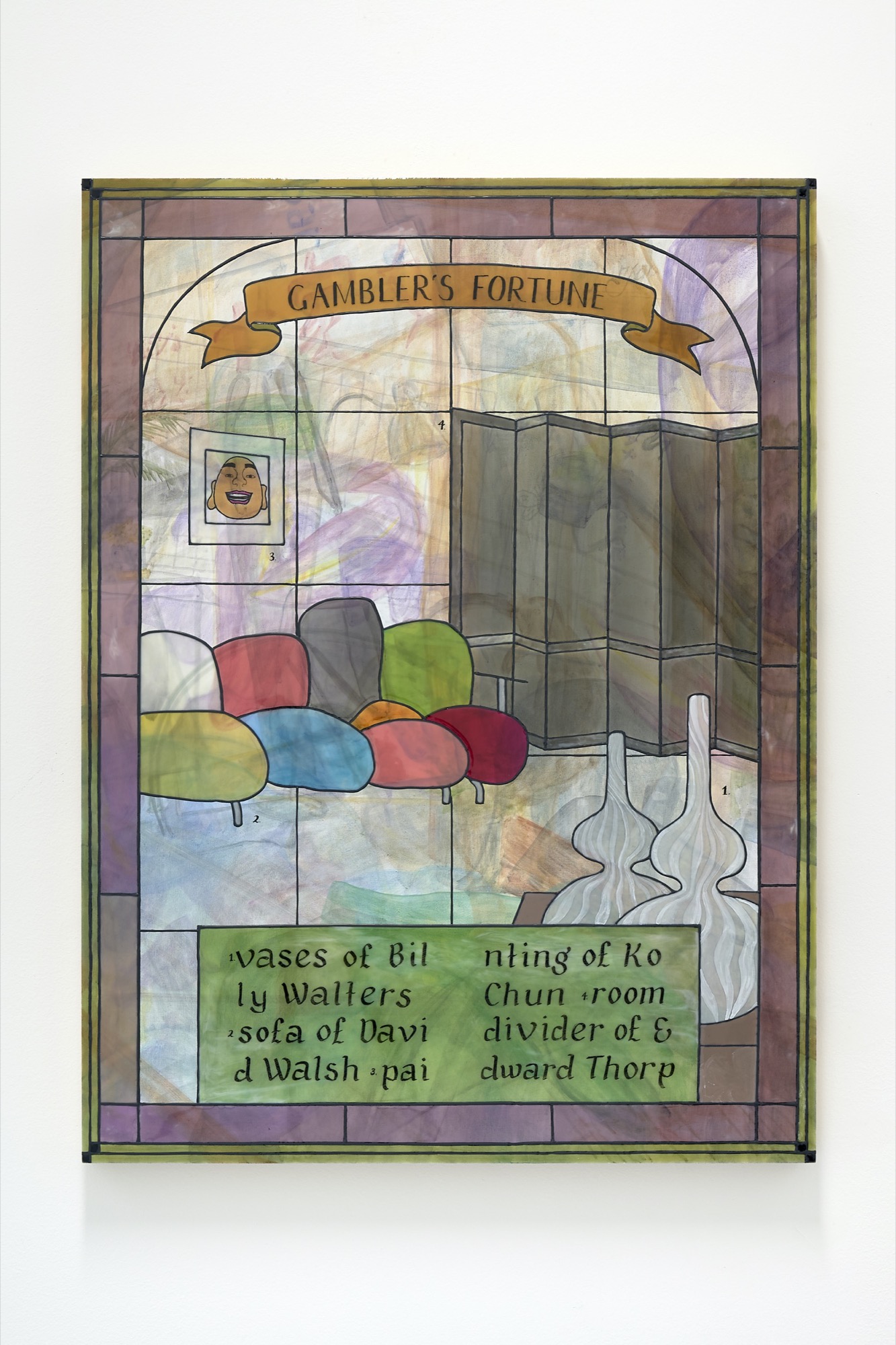

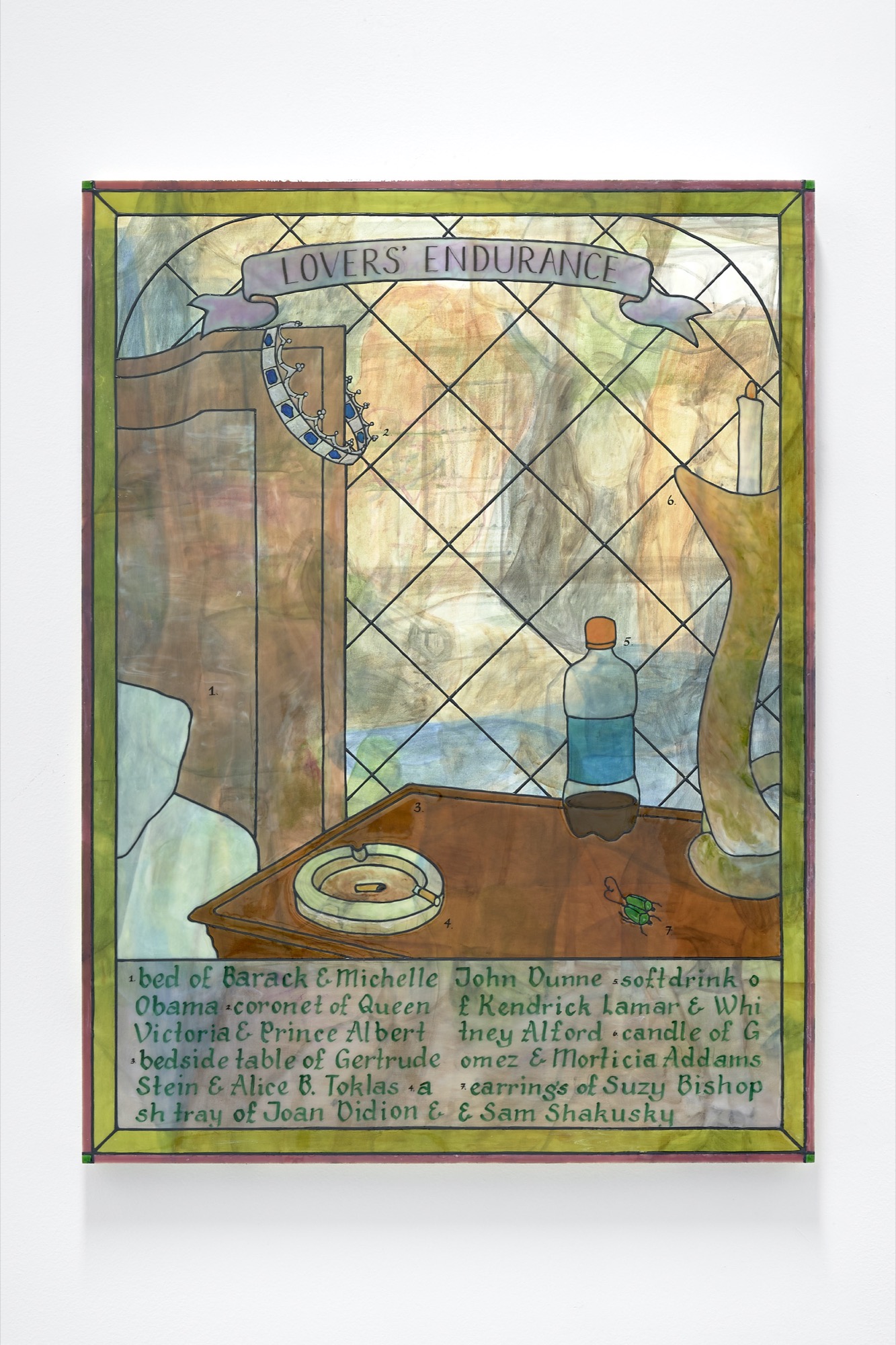

Koo has previously exhibited both paintings and sculptural installations but here has carefully built three works of identical dimensions, with simulated liquid leading, paint and resin applied to a plywood support. As such the works initially read as paintings, alluding to the painting-as-window trope, and Koo has rendered the scenes from “outside” in blurred, translucent oils. This layer functions to foreground the “glass” of the window, in which, following the format of both Tarot cards and lead-light windows, are three different domestic interiors crammed with furniture, plants, ornaments and household miscellanea. I learn from the neatly painted citations below every object their alleged celebrity pedigree: Jennifer Aniston’s amethyst sits beside Russell Brand’s buddha figure on Adam Levine’s coffee table, and floating above each room a heraldic banner reading “for yogic fortitude” in this case. The other two works follow the same format: lovers’ endurance (2020), for example, features Barack and Michelle Obama’s bed next to the bedside table of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas’ gambler’s fortune (2020) depicts David Walsh’s couch underneath a painting belonging to Ko Chun—a fictional movie-character nicknamed the God of Gambling. Koo has skilfully applied the simulated liquid lead as per its prescribed use, fashioning a lead-light trompe l’oeil faithful to the technique’s graphic lines and flat sections of colour.

Complicating this initial reading, however, are the pine lengths used to brace the plywood, neatly inset with small found objects. These correspond with each work’s title by way of an intentionally pop take on the workings of sympathetic magic—forces that can be harnessed through physical proximity and contact. Therefore, lovers’ endurance (2020) offers the following spicy mix: a whisp of someone’s hair in a stoppered bottle, a segment of rose stem, some kind of pink crystal and a spooky poppet—a doll used in various cultural practices and witchcraft to represent a person. Likewise, gambler’s fortune (2020) holds a piece of chopped-up credit card, a coin, gold earrings and so forth. These talismans, functioning as anonymous but intimate-feeling found objects, strike an interesting chord when considered alongside those depicted in the painted section—which subsequently scream that they’re only representations of celebrities’ former belongings. While these celebrities do exist outside of the exhibition, Koo may well have cooked up “their” objects altogether—though no doubt Gwyneth Paltrow has every kind of candlestick imaginable. In a fact-check mood I googled “David Walsh couch”, but all I got were pictures of Erwin Wurm’s Fat Car. This only is a big deal in the realm of sympathetic magic, where physical proximity or contact are key— “Would you wear Hitler’s jumper?” seems to be a popular question amongst sociologists investigating the theory. By combining “merely” depicted and actual objects, Koo alludes to a logic of lifestyle magazines: a representation of luxury objects pales in comparison to—as well as driving the desire for—private ownership. In terms of physical proximity, ironically the timing of this exhibition means that many viewers may not see the works in person. The found objects become flattened through photographic documentation and a newly popular form: the narrated video walk-through. Koo’s works suit this form though. As a friend suggests, the walk-throughs are like real-estate advertisements: you could just watch the video and imagine the walls are your own, with three Kaijern Koos on display.

Although the three works comprising glistening windows theory (2020) superficially tout health, wealth and good sex, these desires—like celebrity—are so mind-numbingly popular as to almost recede from the viewer’s consciousness, functioning as structural clichés for a more complex investigation. It’s on this point that I depart from the gallery’s framing of the exhibition as “inverting the notion to contemplate the possibility of curating domestic spaces for one’s benefit”—this notion being the controversial “broken windows theory”. I think that this is only a partial description of Koo’s inquiry, and skirts the topic of conspicuous consumption in a way that in fact reinforces the work’s critique. This take isn’t exactly revelatory: in order to sell art, it’s generally in the interest of commercial galleries not to highlight the status of artworks as prestige objects par excellence, lest the buyer become self-conscious. Considering the work as a self-reflexive inquiry into conspicuous consumption—though by no means radical or didactic—what is omitted by the gallery’s framing becomes apparent, namely the ownership and display of artworks as an effective vehicle for upward class mobility and/or the maintenance of this station.

I feel that while glistening windows theory (2020) may have used the “broken windows theory” as an initial prompt and catchy title, this framework alone does not do justice to the exhibition, though it is certainly worthy of discussion. Emerging in the early 1980s, the sociological concept was quickly and crudely misinterpreted, and enthusiastically taken up as an approach to policing across the US, particularly by the New York Police Department. The NYPD’s misinterpretation at least allows for easy summary: minor acts of vandalism like graffiti or window breaking beget more of the same through lack of consequence—and, as admitted by the original theorists themselves, “it has always been fun”—leading to more widespread dereliction and, subsequently, more “serious crimes”. In reality, when this is deployed as a method of policing, the results include mass incarceration, the notorious “stop and frisk” practice of racialised over-policing, and a highly questionable effectiveness in reducing “serious crimes”.

I came across a couple of projects attempting “inversions” of this approach to policing, both of which attempted quite literal material interventions. The first took place within the immediate context of the theory’s rise in popularity, initiated in 1983 by New York City’s then-Mayor, Edward I. Koch. In a bid to sort out the perceived abject dereliction of buildings in Harlem and the Bronx, a third of a $300,000 federal grant was mobilised to print full colour, 1:1 scale vinyl decals of venetian blinds, potted plants and cute curtains, which were then adhered over boarded-up windows in the area. Koch, who claimed the idea as his own, both acknowledged the superficiality of the program and justified it by saying, “In a neighbourhood, as in life, a clean bandage is much, much better than a raw or festering wound”. Understandably, many residents expressed their disdain, arguing that the project was both patronising and a waste of money. It’s interesting to note a shared chain of logic with glistening windows theory: if the “broken windows theory” holds, then surely by vanquishing any broken windows—or even a spruce up with some pot plants and fresh glass—doesn’t it follow that ambiguous “improvement” will appear? Edging towards Koo’s assertation, a 1983 New York Times article opens with, “New York City officials are hoping life imitates art in the South Bronx”, and one such official is quoted as saying “perception equals reality” and “morale is very real”.

The second is a contemporary example, as presented by Hito Steyerl in her 2018 installation, The City of Broken Windows (2018). Two videos form the core of the work: Broken Windows (2018)—shown recently as part of Machine Listening, a curriculum, curated by Joel Stern, Sean Dockray and James Parker for Liquid Architecture—and Unbroken Windows (2018). The former is an advertisement-cum-documentary-style work, observing employees of the company Audio Analytic as they methodically smash glass panes in order to harvest the audio and feed it to their AI surveillance software. While Steyerl’s video certainly reveals that the “broken windows theory” is thriving as an approach to surveillance and policing, Unbroken Windows is like the artist-driven version of Koch’s decal program, minus the community disapproval. Steyerl follows “artivist” Chris Toepfer through New Jersey as he and his organisation, the Neighbourhood Foundation, along with community members use carefully painted panels to replace the plywood used to board up abandoned buildings. In one of the video’s stills, I find, a particular painted board that looks uncannily like the New York City decals—and I wonder whether this is a coincidence. On the Neighbourhood Foundation’s website, I find more before-and-after images; panels painted as neat, curtained windows, sometimes a pot plant or two.

While Unbroken Windows (2018)—or more accurately, Chris Toepfer’s project—and the New York City decals function through their literal opacity and ownerless display, Koo’s works instead belong to the domestic space, and coax the gaze toward the private property of interior spaces. Rather than a collective covering over of the “unsightly”, glistening windows theory emphasises windows’ transparency. The exhibition’s conceit is asserted most clearly in Koo’s evocation of windows as portals, through which these interiors can be flaunted and spied upon, as well as the possibility of the glass itself to become a prestige-item. In appropriating the style of lead-light windows, Koo has identified a highly successful form of disposable-income-signalling in the domestic environment. While impressive frontages, or lavish interiors are visible only to those either inside or outside of the space, lead-lighting—most often installed around the front windows and door of a house—is simultaneously visible to both. In Australia, the upwardly mobile nouveau riche of 1920s considered lead-lighting as the must-have ornamentation of the day, with one of the world’s best-preserved collections scattered across the now-affluent Perth suburb of Subiaco. Upholding this historical and colonial impulse, the City of Subiaco extolls a self-guided walking tour of the area. A council pamphlet reads, “Reminiscent of an open-air art gallery, Subiaco allows passers-by to get a glimpse of the past and an insight into the generations who built this great city”. It’s the unabashed classism of conspicuous consumption, and this breathy reverence for the lead-light that glistening windows theory (2020) both teases and teases apart. The form’s self-seriousness is sent up by the works’ satirical tone. The objects painted by Koo allude to a fervent and hilarious desire driving people to buy even the most obscure objects, according to their proximity to celebrity—particularly if this association was one of physical contact, ie. sympathetic magic in action. For example, the artist may well have included Justin Timberlake’s half-eaten French toast, auctioned off and purchased by a teenage fan in 2000, who then vacuum-sealed it and put it on her dresser. By comparing this want with more “sophisticated” desires for art, or lead-light windows, Koo sends up the self-seriousness of any gaudy displays of what are considered prestige-items.

Koo’s works acknowledge that displayable art is particularly coveted by the conspicuous consumer, and double down on this by being available for purchase at a commercial gallery. Ko Chun’s painting in the gambler’s fortune (2020) room mirrors this nicely, and Koo’s canny allusion to the domestic lead-light is my favourite aspect of the show. While the New York City decals were ill-conceived and patronising towards community members, perhaps Koo’s works turn this energy towards the wealthy art collectors proximate to the exhibition. It has to be said, though, that while there are many practices critical of art’s investment in the system of conspicuous consumption, it doesn’t seem to perturb consumers that much. Vogue Living recently featured an opulent Toorak mansion boasting both “Gucci in every room” and Russian art collective AES+F’s The Feast of Trimalchio, Arrival of the Golden Boat (2010) on the wall. The video, The Feast of Trimalchio (2009-2010), from which the collage is drawn, presents a hyper-indulgent world of self-obsession, materialism and consumption. In an image caption, listed alongside the artwork are a “vase by the Campana Brothers from Artemest; acid marble table lamp by Lee Broom from The Future Perfect, enquiries to Space Furniture; vase by John Booth”. Vogue Living’s writer seamlessly folds her description of the work into the article—a “digitally collaged tableau, telling of the gluttonous trappings of wealth within a classical framework”—and the piece goes on.

In a written accompaniment to the exhibition, Koo affectionately teases poet Ariana Reines’ lament that despite the identical content, the second edition of her book, A Sand Book, is not really the same, due to the less shiny detailing on the cover. More than merely an inversion of the “broken windows theory”, it’s a poem from Reines’ earlier book Couer de Lion (the first edition of which now sells for hundreds) that perhaps expresses both the fundamental irreverence and self-reflexive critique of Koo’s glistening windows theory (2020):

She is the Gallery Girl.

I know what that’s about.

I was the Gallery Girl. I tried

To like it. It was important

To pretend to be interested

In being near artists and art

As though proximity were tantamount

To metonymy, which it isn’t, not in real Life.

What’s metonymy

In real life. You rub up

Against something; some of its

Truth and incompleteness

Is transferred onto you;

You carry it around on

Your body. Maybe. Art. That fussed

Trite shit rich people buy.

—Ariana Reines, ‘Coeur de Lion’ (2007), page 4

Amy May Stuart is an artist living in Naarm (Melbourne), Australia.