Jus Diddit: A Community Unfurling

Laura Luciana

Jus Diddit: A Community Archive Unfurling is stubborn because DIY must be stubborn. It exists on precarious budgets and feeble resources, despite the wilful blindness of major institutions. And DIY is made manifest at Pari, an ARI situated on the outskirts of Sydney, in relation to but independent of inner-city Sydney’s purported cultural prominence.

Taking Western Sydney as its starting point, Jus Diddit asks: what does it take to create vibrant communities and resonant subcultures, and where do you start? For the local ravers, punks, and queers celebrated and archived in Jus Diddit, the answer is simple: they just did it. Curators Levent Can Kaya and Carmen Mercedes Gago Schieb speak in the language of the scenes because they inhabit these scenes.

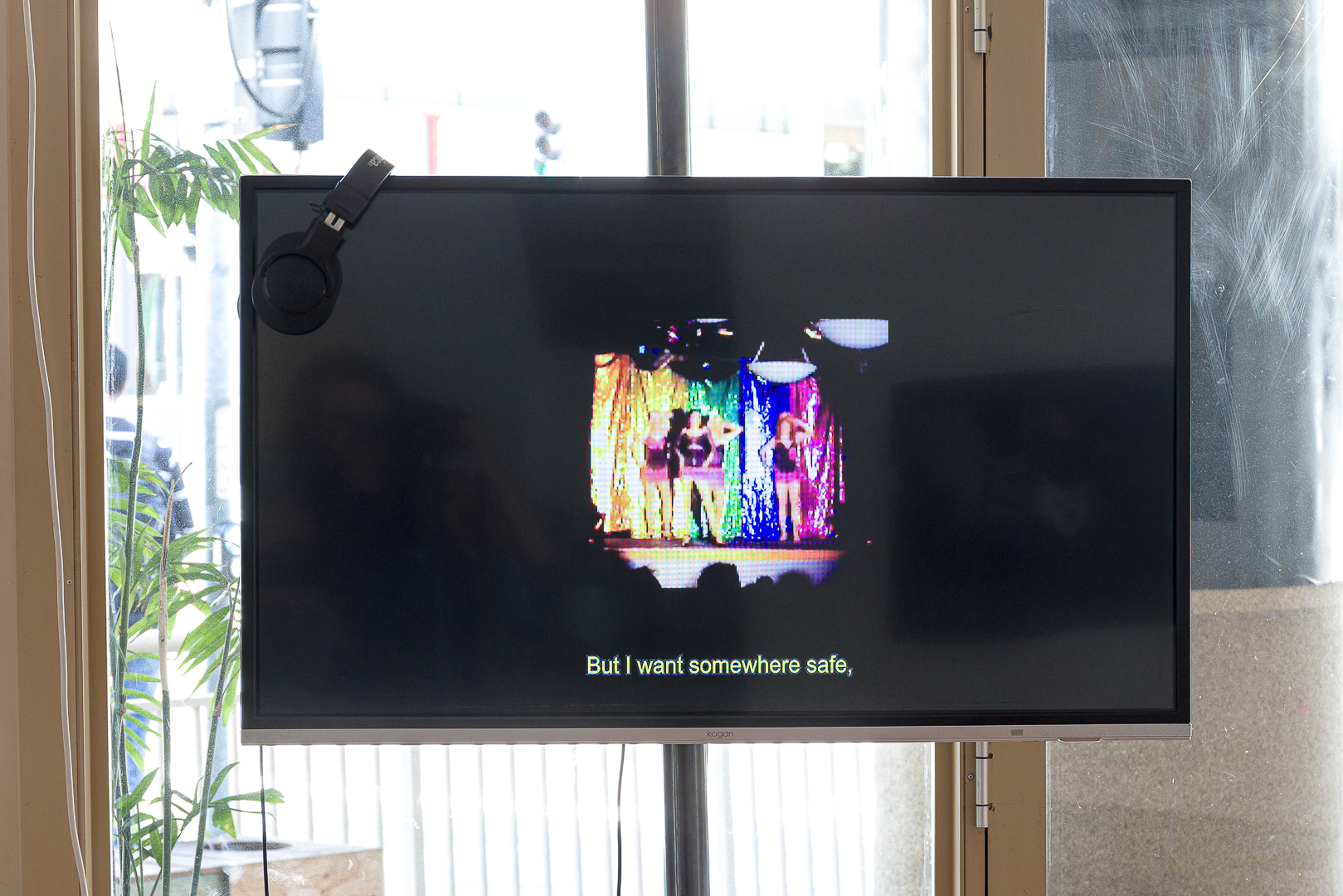

And there’s a lot of talking in Jus Diddit. Gago Scheib and Kaya conducted and filmed several interviews with central figures of local punk, hardcore, rave, and drag scenes, which they put on display for us to listen to alongside ephemera from these scenes. By nature, DIY punk shows, raves, and queer and drag artists have had to exist on the margins and evade regulation or visibility for their safety. Because of the curators’ unique positionality and compulsions for these scenes, the interviews reveal an agile and sensitive insight into these subcultures.

In their interview, the 200+ BPM Is My Safe Space party organisers look hostile in their balaclavas. Was Jus Diddit “blowing up the spot” by creating this new community archive? Anonymity is necessary for 200+ to preserve their ability to organise raves that escape regulation in the Mountains and remain accessible to their communities. While they remain concealed, another softer, more charming truth is immediate: their benevolent politics are at the forefront of everything they do. They speak to the importance of making 200+ safe for their queer and femme communities, that 200+ became a solution to the problem of unsafe communities elsewhere, and that they “can’t change that scene but can create that somewhere else.”

Sometimes, while watching the interviews, it is like listening to an adult conversation as a kid; you’re allowed into something you always hoped to be on the precipice of finding. In a conversation between the curators, we learn about the precise moment their archival research began. In 2021, they were celebrating Mardi Gras in Western Sydney at a drag bingo night. “Wasted” in the smoking section of Club Parramatta, Kaya and Gago Schieb started dreaming about starting a nightclub in Western Sydney. Then, an old drag queen hosting the bingo night came over and “schooled” them. Kaya and Gago Schieb recount: “She sat us down and said, ‘Hey, like this is how you start a nightclub. This is what we would do back in the day. And if you want to know about what was happening back in the day in Western Sydney in queer communities, you need to find Beverly Buttercup’.”

They eventually found Buttercup. And her radio show, website, timelines, and photographs. She revealed a history that felt triumphantly rooted outside Sydney’s gay districts of Oxford Street and the Inner West. In an interview with Buttercup, she describes her “first gay nightclub experience” in the early 1990s at “The Midnight Factoree at Penrith… it was a little club in a warehouse in Penrith, and everybody knew everybody.” She recounts the changing scenery, characters, and venues she and her collaborators repurposed for club nights, performances, and social dances from Penrith to Campbelltown and Moorebank. She articulates the complicated changing needs of Western Sydney’s queer subculture, from nightlife to a place to explore sexuality, collaborating with lesbian initiatives and social settings for conversation and community. The interview ends with Buttercup’s call to action for the continued de-centralisation of queer community in Greater Sydney: “I think it’s really important to keep something in Western Sydney. I hope that if I don’t do it then someone steps up and does something.”

Much can be said of “community”—this potentially fragile thing; we often feel scepticism if it isn’t historical, familial in the strict sense, or ethnic. Conversely, we have too much faith in an abstract and imaginary community—like how some of us throw around the phrase “gay community”. The problem of what a community actually is and how we archive or exhibit it is complex and fraught. It requires a certain level of collaboration and mutual understanding, including, I’d say, between the curator and the exhibition’s subjects.

Archival research into punk or queer or otherwise countercultural scenes is tricky. Because they are partially made of immaterial things, people, and time spent together, they refuse to solidify into History. As the late Cuban American theorist of visual culture José Esteban Muñoz argued in his now iconic book Cruising Utopia of 2006, ephemerality structures the queer archive. After Muñoz, the punk or queer archive can’t just be about collecting or recounting the past or theorising the significance of yesteryear’s warehouse parties, underground club nights, drag performances, mountain raves, and live shows at indie record stores. We must also be willing to participate in the scenes to reconstruct the archive meaningfully, poetically, vibrantly and with resonance with the key “stakeholders.” Exhibiting this archive in Western Sydney is about being invited into a closed circuit of people doing things by and for each other. It is about imagining the futures that could be created with each other, that could identify and fulfil needs that institutions can’t or won’t achieve.

In Parramatta’s beloved Pari, Kaya and Gago Schieb have wheat-pasted flyers from fastidious documenters of the individual scenes, who also contributed photos that have been blown up on Pari’s walls, videos that soundtrack the interviews, and iPhone pictures that scroll on a phone in the gallery space that feel like you’re looking into a party that happened last night. I love the obsessive efforts of the community documenter, seeing the troves of ephemera arranged into an exhibition that feels humble and resplendent at the same time. Being invited into the objects and storytelling of their making positions you as part of this “unfurling.” “Unfurling” is gentle; it invites continuity and persistence. Unfurling is just a start.

On March 16, Kaya and Gago Schieb hosted Jus Diddit: The Gatho in the Pari carpark. Part “gatho”, part party, part public program, Kaya and Gago Schieb curated punk-driven noise performances that look ahead to new DIY collaborations. The audience gathered in the lowlight and unforgiving concrete of Pari’s backside in anticipation of Area (Western Sydney)-based artists and collectives Sefi (DJ), TBX, Bract, and Gago Schieb’s noise project, Society of Cutting Up Men (SCUM), in her first collaboration with queer pole witch collective Club Chrome. While “unfurling” might be gentle, this performance was not. Dancers with fake blood were scored by SCUM’s improvisational thrashing chains and a staunch reading of Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto (1967). The manifesto is known for its somewhat violent intentions to rid the world of “useless” men, and it is reactivated forcefully in Gago Schieb’s performance; but in the same breath, it celebrates and uplifts the “grooviness” of women, their capacity for joy, and creative power. The crowd received it with a standing ovation.

DIY exists outside of traditional institutions. It resists the gallery or museum and circumnavigates reliance on grants or private models of art and performance. This may be why Jus Diddit feels entirely at home at an ARI. Nonetheless, the DIY community makers felt resistance to the idea of curation— “Why do you want my crap?” No one ever did it—organise, play or photograph gigs—for recognition or glory. They did it because they wanted to be with each other and do something for their community. What’s more “community” than that?

Laura Luciana is an artist and writer working on Dharawal and Gadigal land. She is currently undertaking Art Theory Honours at UNSW A&D and is thinking about talking, creative labour, and jerking off.