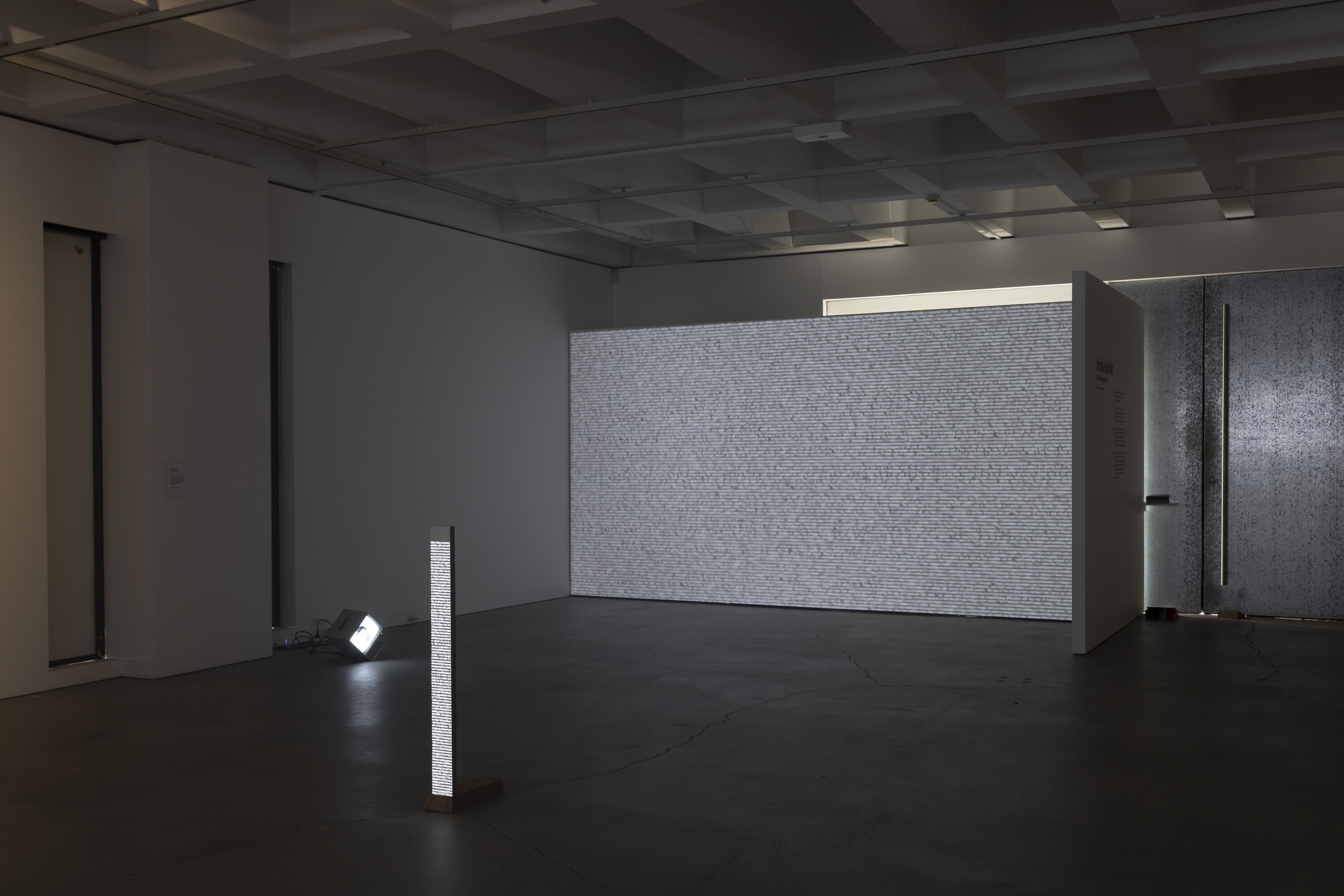

Denis Beaubois, After the Phrase, 2021, 4k video presented as HD, reflective surface, list of the verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901-2021, duration: 157 minutes. Photo: Jessica Maurer

Indivisible

Lachlan Thompson

When a member of the Australian parliament speaks, they exceed their status as an individual. Upon being elected, a Minister of Parliament is sworn into office at Government House in Canberra and under the guise of the Crown’s representative, the Governor General, they swear allegiance to the British monarch. Through this chain of oaths, affirmations and promises, the speech of the MP is sanctified by the State’s sovereign—the British crown and therefore the divine province of God. They speak for more than themselves, they speak for “the people.”

The materiality of the parliamentary speech is realised through specific practices and procedures: the promise, the oath, going on the record, declarations, motions. This speech begins with a sanctification, is transcribed, slid (as paper) across desks, folded, crumpled, cited, chanted, yelled. Such utterances materialise as formal documents, Hansard records, bills, votes—it sprawls out through the numerous arms of the State’s power. This materiality speaks to the possibility of resistance.

Denis Beaubois’s show Indivisible, curated by Dr Mark Themann at the University of Sydney’s Tin Sheds Gallery, is an examination of how parliamentary language since Federation “has been used to describe or prescribe the qualities of a nation over time.” In particular, Beaubois is interested in the “cumulative impact of words,” and the different registers of their materiality which produce, reproduce and maintain the nation.

The exhibition is primarily a showcase of a body of work made during Beaubois’s time as the inaugural Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Create NSW Visual Arts Fellow in 2018. Underpinning the show are two datasets: the transcripts of Federal Senate and House of Representatives proceedings between 1901 and 2024, sourced from Hansard with the help of researcher and hacker Tim Sherratt. Beaubois worked with programmers Snow and Kyan Tan to “text-mine” these datasets to create a list of all verbs and adverbs that follow the words “Australians are.” This list makes up the source material for seven of the ten works shown in Indivisible.

Indivisible immediately falls within the genre of what Claire Bishop has characterised as research-based art. Taking place within a university art gallery and being developed within both institutional and university-based programs (such as the Rex Cramphorn Studio Residency, also at the University of Sydney), the development of the show bears overt markers of the genre.

Looking to the work itself, Bishop proposes that a key heuristic for examining research-based art is through its engagement with forms of data and information, such as the archive, the government document, or the eyewitness account. In this definition, Beaubois’s work sits alongside the practices of artists such as Archie Moore, Julie Gough, James Nguyen, Katerina Teaiwa, and Nicholas Mangan, to name just a few. Crucially, this framing offered up by Bishop poses a latent tension within research-based art. On the one hand there is the reconfiguration and critical engagement with data, and on the other is the reproduction of power that exists within and is enacted by information’s content and form.

Left: Denis Beaubois, Two Fronts—A Document, 2023, 4k video, filmed on location at Airspace Projects, duration: 18 minutes; Right: Denis Beaubois, Two Fronts, 2023, Industrial fans, builders plastic, Australian red cedar (impeding fan oscillation), air flow as fixing agent. Photo: Jessica Maurer

The first sound you hear upon entering the gallery is a low hum. In the far corner of the space is Two Fronts (2023), in which the wind from an industrial fan fixes a square sheet of black builder’s plastic to the wall. Amongst the materials listed is “air flow as fixing agent.” The work is deceptively simple and considered. The speed of the fan corresponds to the naval metric of measuring wind, Beaufort 3, which is derived from an empirical marker: the speed at which a light flag will completely unfurl. The builder’s plastic is cut to the dimensions of a Swiss flag, signifying neutrality. The square also evokes Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, which the artist installed to mimic the portrait of the nation’s leader, and which it was recently discovered is also underlaid with a racist joke. This supposedly neutral form is at once signified and told to us as a tainted reality through these aesthetic and historical references.

At the centre of the gallery is To Fill the Air (2024). A circular projection on the floor of the gallery shows footage filmed using the Schlieren technique, which makes the interaction and flow of hot and cold air visible. Shown in the projection is the residual air flow produced by speaking the entirety of the text-mined list. Filmed in a single two-hour sitting and replayed in slow motion, the work runs for just over nine hours. As Beaubois puts it, “it suggests a 120-year filibuster.”

Using a complex network of concave mirrors, lights and pinholes, Beaubois’s emphasis on the intimacy of breath as a residual materiality of speech doubles as an emphasis on the individual. Beaubois proposes a delicate materiality of parliamentary speech—not only entangled with the living, breathing subject, but as the breath of the nation-state itself.

Front: Denis Beaubois, To Fill the Air, 2025, 4k video, list of the verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901-2021 spoken into space and captured using the Schlieren imaging technique, duration: 560 minutes; Back: Denis Beaubois, Indivisible, 2024-25, Australian red cedar salvaged timber, Surian cedar veneer (Malaysia) sold as Australian red cedar, audio transducers. Audio: List of the verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901-2021 delivered in yearly bursts, AI generated voices with Australian accent. Photo: Jessica Maurer

In an alternative description of To Fill the Air, offered on the MCA Australia’s website, Beaubois describes the body of work as “a sort of litmus test to see if there is a familiarity (resonance) with the language used or whether there is a distance or opposition (resistance).” What is hinted at here is Beaubois’s orientation as artist/researcher—he assumes the position of a mediator, a kind of scientific impartiality. Beyond this methodological positionality, we can take further cues from the term “text-mined.” The implication is that, yes, the words are extracted, but more so, that this extraction entails a removal. While we are told what the list contains, the timeframe it draws from and the rules that it follows, the form of the list poses an issue for its content. What is elided from language as it is text-mined and processed into a distinct and sterile list are the conditions under which it was spoken. In this form, language is flattened into general and uniform contexts, restricting the ways in which it is legible and readable. In other words, the conditions under which a sentence is uttered are part of the materiality of language—without it, the dataset remains largely obscured and impenetrable.

Denis Beaubois, After the Phrase, 2021, 4k video presented as HD, reflective surface, list of the verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901-2021, duration: 157 minutes. Photo: Jessica Maurer

After the Phrase (2021) and All (2025) turn their attention from the spoken to the transcribed word. Here both projected works continuously scroll through the text-mined list. After the Phrase is configured as a single line spanning an entire wall of the gallery, with the words stretched and squeezed into a barcode or sound wave-like form, only readable in the reflection of black acetate rectangles placed at the base of the projection—a reference to the “black mirror” of our phones. All, on the other hand, is a jittering wall of words, which have been taken out of focus by the projector. Placed further from the wall, at the projector’s focal point, is a thin piece of Red Cedar, which offers a sliver of legibility. Both works share a similar aesthetic tactic, presenting the pure scale of the text-mined list, which, alongside aesthetic intervention, obscures the text from view. The list is left floating in space.

Denis Beaubois, All, 2025, Computer, Python script running the list of sentences that contain the phrase ‘Australians are’ from the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal House of Representatives) 1901-2024, Australian red cedar timber, duration: infinite loop. Photo: Jessica Maurer

Placed around the gallery is Ellipsis (2024-25), a collection of seven portrait-style videos, in which participants (test subjects) are asked to memorise and then recite a section of the text-mined list. Each video is shown on a CV monitor, propped up on its edge by a piece of red cedar. The precarity of the monitors is mirrored by the stuttered delivery in each video, as each participant struggles to recall phrases and words. Looming over these monitors, echoing their unsettled stance, is A Resting Weight (2025), in which the artist has balanced a Maple wood dining table, which was sold as Australian Red Cedar, on its corner, leaning against the gallery wall. Red Cedar and its counterfeits, along with air or breath, is one of the recurrent materials throughout the show, which offers a historical reference point. Red Cedar trees were forested so heavily upon English arrival that restrictions were placed on felling them as early as 1802. It thus remains a highly sought after and fetishised wood, specifically bound to the early periods of English invasion. Most poignantly, however, Red Cedar can be found throughout the décor of parliament house, and in the case of the New South Wales Parliament, prior to Federation, Red Cedar was used to construct the Vice-Regal’s Chair in the Senate, which seats the Governor General or the British Monarch.

Left: Denis Beaubois, A Resting Weight, 2024-25, Australian red cedar, maple wood table sold as Australian red cedar, dimensions variable; Right: Denis Beaubois, Ellipsis, 2024-25, Standard definition video, CRT monitors, Australian red cedar. Audio: List of verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901 to 1905 committed to memory, duration: seven loops, duration varies. Photo: Jessica Maurer

The work which gives the show its name, Indivisible (2024-25), presents this materiality in its clearest relation. The work attempts to play an AI-generated audio of the list, divided into intermittent bursts with each burst containing one year’s worth of words, “through” two pieces of wood: one a Surian Cedar veneer sheet, from Malaysia, which was sold as Red Cedar; the other a salvaged Red Cedar log. Beaubois’s use of Red Cedar and its counterfeit as a “resonator” reduces words to simply vibrations and sounds; but, in doing so, states a specific historicity contained within parliamentary language and extending though the counterfeit. This passing of speech through Red Cedar offers a precise material relation that encapsulates the Australian nation’s persistent coloniality and its possible relationships to language.

Left: Denis Beaubois, Indivisible, 2024-25, Australian red cedar salvaged timber, Surian cedar veneer (Malaysia) sold as Australian red cedar, audio transducers. Audio: List of the verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901-2021 delivered in yearly bursts, AI generated voices with Australian accent; Right: Denis Beaubois, A Resting Weight, 2024-25, Australian red cedar, maple wood table sold as Australian red cedar, dimensions variable; Front: Denis Beaubois, Ellipsis, 2024-25, Standard definition video, CRT monitors, Australian red cedar. Audio: List of verbs or adverbs that follow the phrase ‘Australians are’ in the Hansard transcript (Australian Federal Senate) 1901 to 1905 committed to memory, duration: seven loops, duration varies. Photo: Jessica Maurer

Beaubois’s considered material resolve, and attention to aesthetic intervention is undeniably effective. However, within many of the works throughout the show, the form of the list remains dominant. For Bishop, the best research-based art practices “emerge when preexisting information is not simply cut and pasted, aggregated, and dropped in a vitrine, but metabolized by an idiosyncratic thinker who feels their way through the world.” Beaubois’s text-mined list does, indeed, meet Bishop’s overarching definition; however, in its production, the list flattens and sterilises language by extracting it from its material, historical and lived contexts.

The most striking works, such as Two Fronts and To Fill the Air, see a synthesis or “metabolisation,” which both draws upon and exceeds the form of the list and its “preexisting information.” In these moments, Beaubois convincingly articulates the precarity of the nation and its ideologies through the intimate materialities of breath, speech, and history. These alternative registers of statecraft and nation building offer renewed ground for the critique of the nation. That is, that the solidity of words is bound to the precarious practices though which they are uttered in the world—as an order, a promise, an oath, a whisper, a lie, that gentle breath which unfurls a flag.

Lachlan Thompson is an artist and writer based on Cammeraygal and Gadigal land.