Georgina de Manning, Scroll, 2023, 5-channel digital video, digital sound, televisions, computer monitors, vinyl prints, LED strip lights, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror

Judy Annear

I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror is populated by works focussing on bodies, human and machine, that either metaphorically or literally extrude. Oddly, there is nothing particularly visceral about the works, perhaps because several depend on the grid as a frame. Further, the structure of I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror makes it clear that being within these spaces is durational; the exhibition is therefore also about the dynamic body in time. As a visitor, I was drawn to consider each work and its relationship to my own body, the spaces we inhabit together, and how the works relate to each other. This awareness was heightened by the appearance of objects and substances close to the body—hair, food, internal organs, heartbeats, voices—as well as flashing lights, rats, butterflies, the moon, obvious and not-so-obvious fakes, repetitive and compulsive movements. There were things that look like other things yet were not, abrupt changes in scale, and the possibility, if not probability, of disintegration and collapse.

The title may riff off and invert the pop romanticism of Temples’ song, “I Wanna Be Your Mirror” (2017) or challenge the abjection of The Velvet Underground’s “I’ll Be Your Mirror” (1966). Another conceivable link is the twentieth-century French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s “mirror stage,” a stage in human development when a child recognises themselves in a mirror yet does not recognise that the image is not who they are. I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror is both acknowledgement and rejection of the conventions of representation.

Christina May Carey, Embodied tendencies, 2023, single-channel HD video, 16:9 aspect ratio, colour, stereo sound, 6 minutes, 35 seconds, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

The exhibition was curated by Alicia Frankovich and contains the work of seven early career artists. I think of it as a considered, luminous project. An artist, performer, and teacher, Frankovich is noted for her interest in and work with transitory spaces, objects of becoming, and their relations. In her hands, these objects become fluid subjects, retaining their integrity yet clearly existing in subtle interplay from one form to another. Frankovich often works with groups of performers, most recently in Rich in World, Poor in World in Melbourne Now (2023) at the National Gallery of Victoria. Her expertise in working with groups of humans carries over to her “solo” work with her own made objects, such as in Spaces Of Life (2024) at 1301SW, where she took, among other industrial items, Tesla airbags, and brought their dynamic relationship to flesh and body fluids to the fore. By disinterring and re-presenting the contents of such objects (normally hidden from our sight), Frankovich revealed their impressions of human body parts. These objects show the ambiguities of their protective design. If humans “crash,” what do we become? I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror, ostensibly her second “curated exhibition,” rests on twenty years of collaboration with animate and inanimate matter.

I was fortunate to see I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror twice, four weeks apart. The precarity, even state of collapse, of some objects was evident on first viewing. This was, in some instances, more pronounced a month later. In others, the fragility of the object was maintained, and a fine balance was evident. This balance was apparent not only for the object in question, but for the relationships with and to others throughout the exhibition. Frankovich has referred to these relationships as being like a figure 8. As the audience moves through the various rooms at the La Trobe Art Institute, the artists’ works move together and apart according to a viewer’s position and perspective. Those relationships are ever-changing according to the many variables of air, atmosphere, time of day, numbers of visitors, and how the works are slowly (or not so slowly) changing. Transiting these spaces is also akin to traversing a Möbius strip, another symbol of endless encounters. I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror is certainly not static. Perhaps the “anti-mirror” of the title also, elliptically, refers to physics, to the particles that, in meeting their opposites, caused The Big Bang. An expansive energy is released.

Rachelle Koumouris, My Tail Is A Counterweight To My Big, Soft Head, 2023, chair, wood, steel, clay, adhesive, enamel, rubber, plastic, varnish, eucalyptus oil, mica, 120 x 85 x 85 cm.

Silly Monkey (1–3), 2023-24, hubcaps with aluminium, wax, adhesive, nail polish, 3 parts, each 40 x 40 x 15 cm, all courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

The North Gallery contains the work of four of the seven artists—Christina May Carey, Erin Hallyburton, Rachelle Koumouris, and Zeïna Thiboult. On my second visit (but not my first), I noticed the faint smell of anise. Everything in the North Gallery is on the verge, teetering. Carey’s Moon II (2023), for example, is contained in a grey metal viewfinder, a structure that seems to suggest greater visual accuracy. Yet the work played with my perception of Earth’s satellite. Unlike Carey’s wall-sized projection, Embodied Tendencies (2023), which occupies the South Gallery, Moon II is scaled right down. I had to bend a little to peer into the small viewfinder, reminiscent of the type built for tourists to view famous locations. Inside, I saw a luminous blue moon. Built from six months of moon viewings during Covid lockdowns, this tiny compression of the familiar entity, the thing that affects everything on our planet all the time, becomes both tangible and more remote. We cannot touch the enormity of the Moon’s affect—or hear it, though we can see it, and feel it subliminally. Embodied Tendencies, on the other hand, envelopes the viewer in an image grid of live things, coloured celestial blue, interspersed with synchronised moments of light and dark.

Rachelle Koumouris’ objects emanate life. my tail is a counterweight to my big, soft head (2023) is anthropomorphic. Built from found objects, the sculpture lurches, ungainly, teetering on what looks like hooves. Nonetheless, it maintains its balance over time (relating hopefully to everything else inhabiting this room). Koumouris’ other piece, Silly monkey (1–3) (2023–24), consists of three circular objects made from hubcaps adorned with fine green filaments topped with tiny red drops. These appear to be on the verge of racing across the floor. The embellished metal, with its circular dynamism, becomes biomorphic—though nothing in its elemental state suggests that this could be or should be so.

Zeïna Thiboult, Hair Bow, 2024, synthetic hair extensions, wire, 457 x 47 cm. Black Halo, 2022, synthetic hair extensions, polystyrene, 40 x 17 cm, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

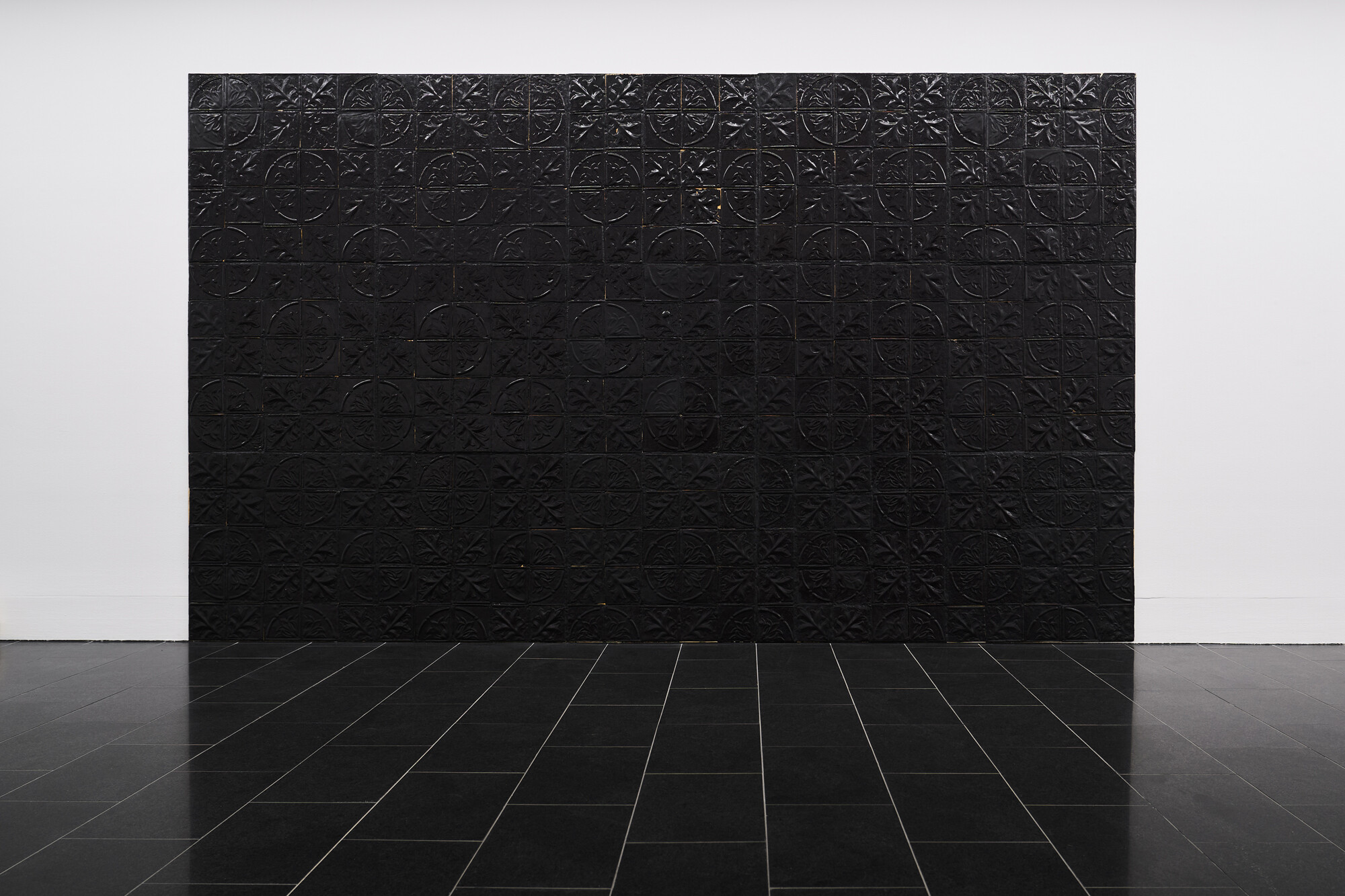

Placed around the perimeter of the North Gallery are various objects made by Erin Hallyburton, the most compelling of which is Sweetly catch in the back of my throat, cold inhale again (2024). Constructed from 375 “tiles,” each fifteen centimetres square, Sweetly catch… resembles, from a distance, a severely modernist work. Closer up, it appears as though a black-pressed tin ceiling has slid down the gallery wall. Sweetly catch… is handmade from black liquorice (hence the aroma of anise). Edible materials, their processing, and their disintegrating remains, are a signature of Hallyburton’s practice. This large work is indeed collapsing very slowly over time, as the sheer weight of a substance as flexible as liquorice succumbs to gravity.

Zeïna Thiboult’s hair extensions (Hair Hearts; Black Halo; Blonde Halo (all 2022); Hair Bow (2024)) allude to the bodies that might carry them. They also exist in their own right. They could be prostheses, but, to switch things around, we could be their prosthesis. This possibility applies to many of the works in this exhibition. What if we swapped places? What world would we live in? The taken-for-granted primacy of human perception falters. Undoubtedly the objects, videos and sounds that fan out through the exhibition spaces are made by humans, but, once made, artworks gain the possibility of a subjectivity of their own.

Erin Hallyburton, Sweetly Catch In The Back Of My Throat, Cold Inhale Again, 2024, handmade liquorice mounted on plywood, 375 tiles, each 15 x 15 cm, installation: 232.5 x 387.5 cm (variable), courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

The works of Hugo Blomley, Georgina de Manning, and Ashika Harper (along with Carey’s large projection) occupy the auditorium, courtyards, and South Gallery. Blomley’s objects depend on the ambiguities of their partly AI-generated forms. Blomley instructs the computer to generate new forms that he can incorporate into his artworks. The overt considerations of scale, material, and recognisability make his work the most formal of any in this exhibition. Yet these objects have a helplessness to them, which emerges from the difficulty in identifying their shapeliness.

Hugo Blomley, Servitude, 2024, patinated bronze, edition 3 of 3, 81.5 x 43.1 x 34.8 cm, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hugo Blomley

Ashika Harper’s audio collage Voicemail (2023) rereads sections of dialogue from The Matrix. The 1999 film was written and directed by the Wachowski siblings, who subsequently came out as trans. The Matrix has become an important text for Harper and others, who see it as a way of examining “trans becoming” and the “idea of a fractured self.” The movie was a highly successful consideration of the nexus between humans and machines and how realities can be manufactured and manipulated. In Voicemail, Harper uses sound and AI to fragment phrases and meanings, encouraging mobility in thought and being through listening.

Ashika Harper, Voicemail, 2023, AI audio collage presented as 4-channel surround sound, 9 minutes, 33 seconds, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

Across the hall from Harper’s work is Georgina de Manning’s engaging use of the auditorium. Empty of the usual audience, the seats are raised to show memes on their bottom cushions. Five videos, part of a work titled Scroll (2023), occupy the perimeter. Outside the door are more memes, their endless output less a matter of invention and more evidence of a desire from their makers for the viewer to notice any absurdity, irony, or horror. De Manning examines who creates the material she chooses to work with and why. She understands that generative AI, for example, is authored by humans. She takes videos and images and reworks them with full knowledge of the material’s initial impetus. One part of Scroll, for example, uses video material of Trump and Putin and places them within a simplified Tetris game. She parodies an auction, revealing the corruption at the core of a system that will sell anything to anyone regardless of social, political, and environmental impact. De Manning does not take the moral high ground here; her focus is simply on making the origins of information clearer.

Georgina de Manning, Scroll, 2023, 5-channel digital video, digital sound, televisions, computer monitors, vinyl prints, LED strip lights, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Leon Schoots

The overlap between the visceral and cerebral is prevalent throughout I Wanna Be Your Anti-Mirror. The body, whether animate or not, machine or flesh, is lively—always ingesting, divesting, inhabiting, embellishing. All subjects, with all their idiosyncrasies, are embraced equally. This is unusual in any group exhibition, and here the seven artists are all in their twenties. It was another positive for me that the artists’ biographies, apart from birthdate and place, were not overly emphasised. Instead, the artists’ voices—accompanied by the voice of the curator, Frankovich—are front and centre. It is rare to see such an engaging and thoughtful project.

Judy Annear is a writer based on Djaara Country. She is an Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne School of Culture & Communication.