I can see Russia from here

Rex Butler

I walk along grimy Waratah Place in downtown Melbourne. The walls of the buildings are black from use, a chef from a nearby Chinese restaurant crouches on the pavement playing on his iPhone. I climb a flight of rickety wooden stairs and enter the gallery. Two young volunteers sit huddled together in front of a computer screen ignoring me, the only person in the gallery, at least as long as I was there and maybe for much of the day.

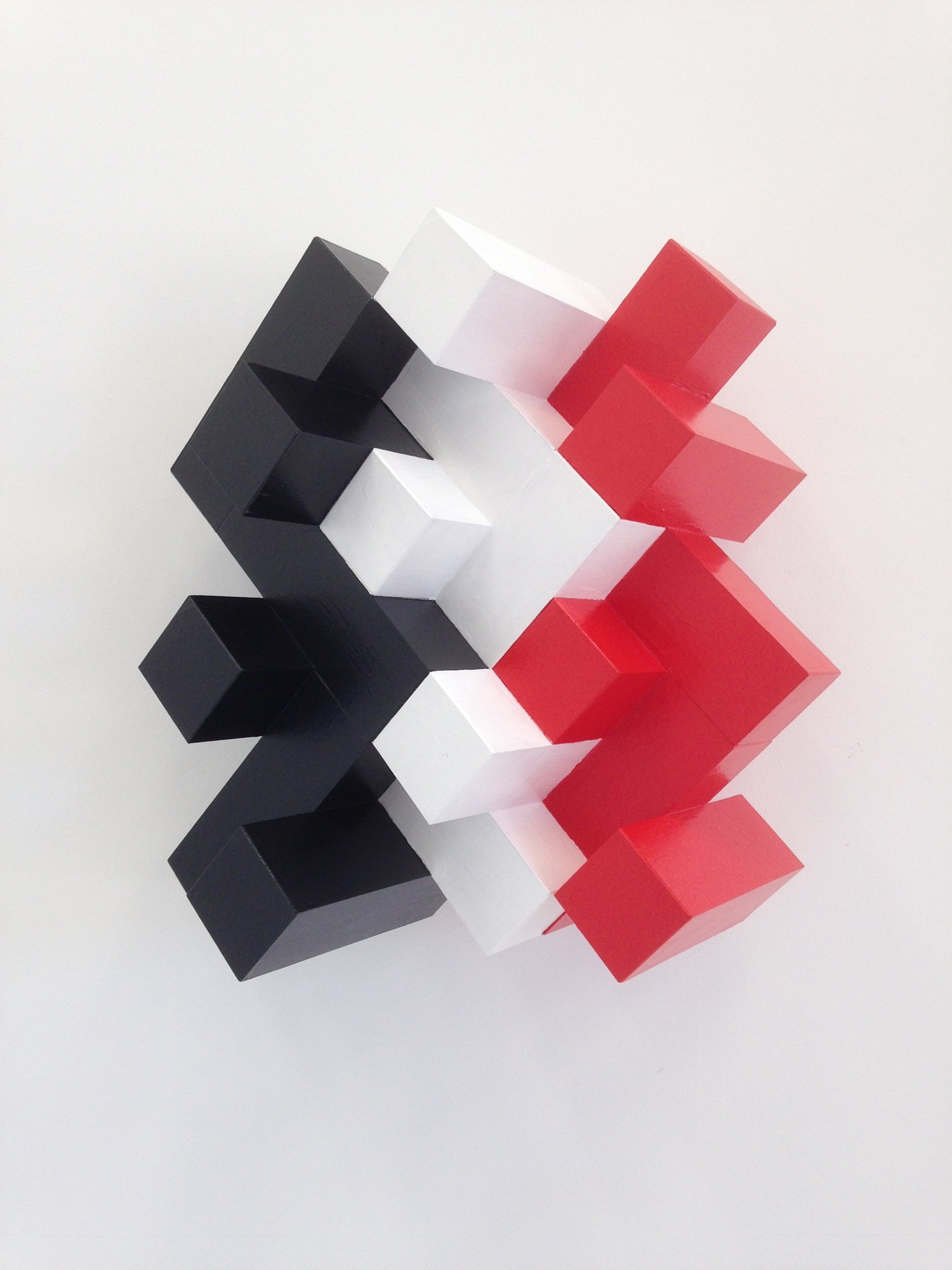

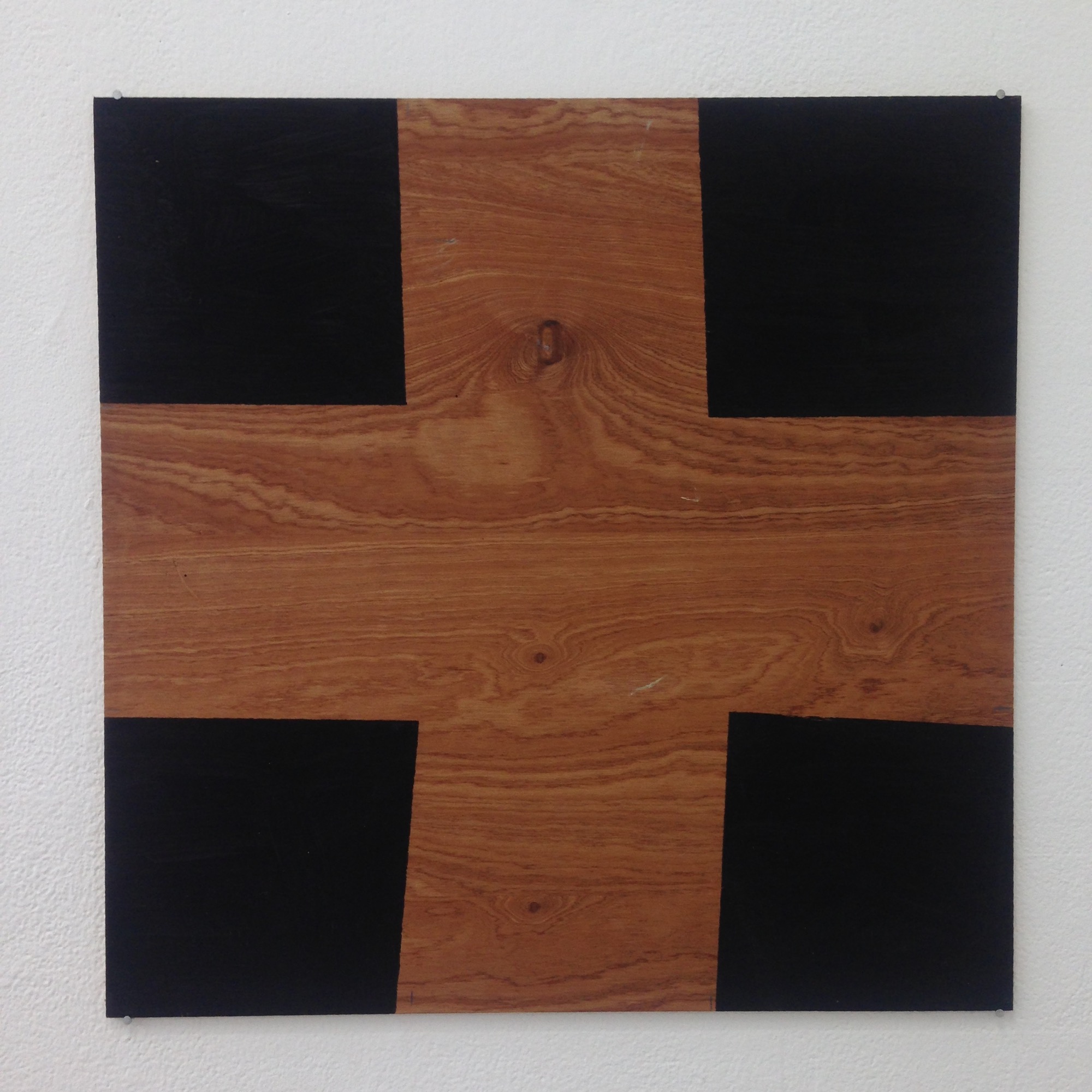

It's a modest show of small, often nondescript-looking objects, spaced evenly around the first of the gallery's two rooms. Perhaps the most immediately recognisable is John Nixon's Black and Brown Cross of 1988, which is really nothing more than four squares of black enamel paint applied to the corners of a sheet of knotted plywood to produce a replica of one of Malevich's famous crosses. But we also see something of Malevich in Gordon Bennett and Eugene Carchesio's Untitled of 1992, which is an aerial watercolour of the globe looked on upon from the intersecting triangles, squares and rectangles of Russian Suprematism, and Bennett's Self-Portrait No. 22 of 2003, which overlays a photo of Bennett with the white female mannequin of Malevich's Girl with a Comb in Her Hair of 1933.

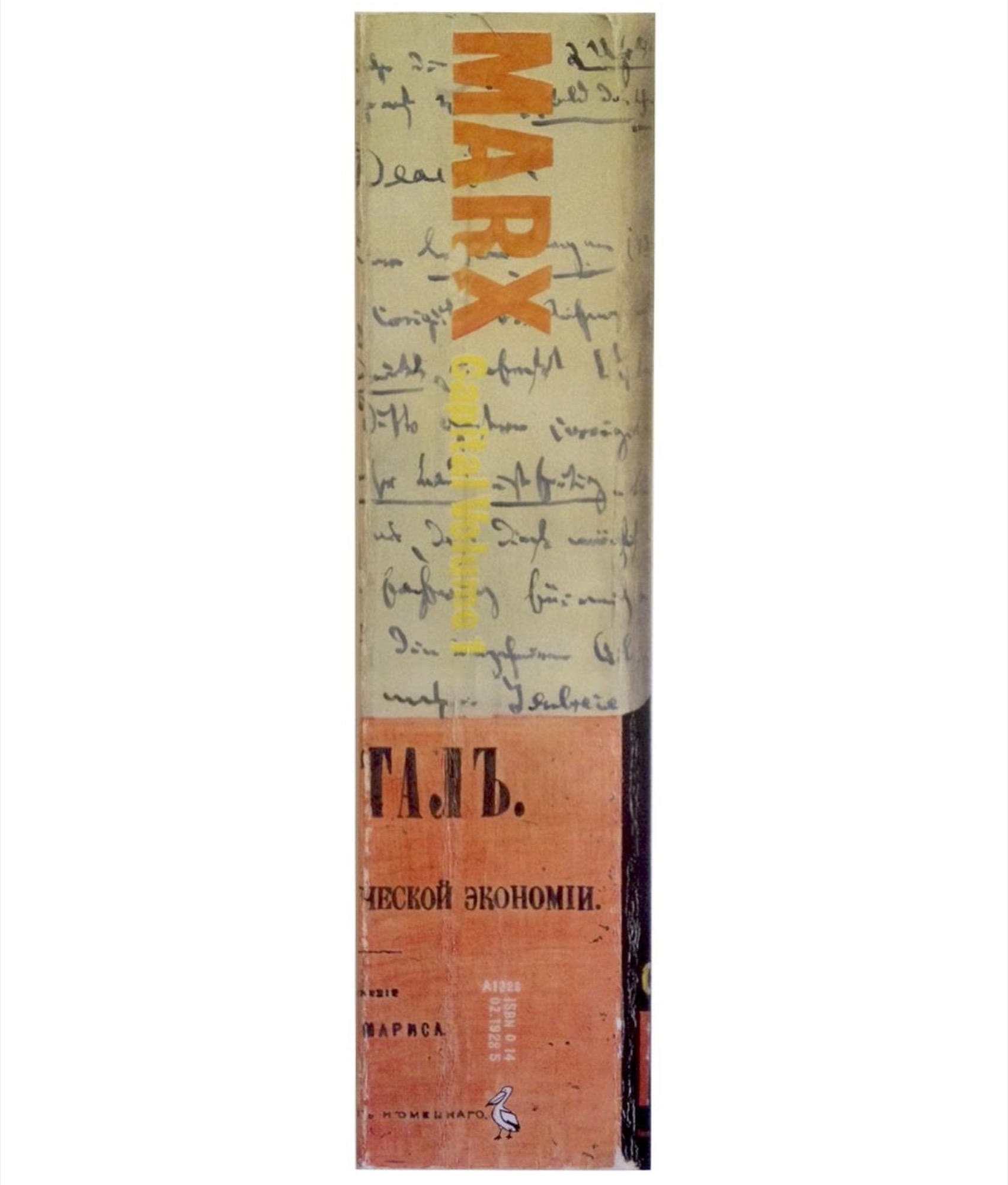

Then again we have Chris Carmody's Dear Comrade, 2017, which features a large blown-up detail from the book jacket of the famous Penguin edition of Karl Marx's Capital Volume I, and immediately to the right of that Meg Stoios' Next Stop, 2017, a digital photograph apparently showing a real commuter on a tram actually reading Marx and Engels' Communist Manifesto.

On the wall facing the door, there is Peter Kennedy's Wall of Ghosts, 1995, four large framed watercolours depicting in progressively disintegrating strokes of red, blue, gray and green the four great figures in the historical realisation of Communism: Marx, Mao, Stalin and Lenin.

Then perhaps moving forward in time we have Jemima Wyman's Propaganda Textiles Swatch Book, 2017, which is a small textiles sample book one has to handle with white gloves of repeated swirling patterns made up of details of contemporary insurgencies and uprisings from around the world: the Scream masks used by anti-government protesters in Yemen in 2011, the luminescent fabrics of the Pink Bloc gay rights parade in Copacabana in 2013 and the daunting black of the anti-nuclear demonstrators who took to the streets of Tokyo in 2011 after the Fukushima disaster.

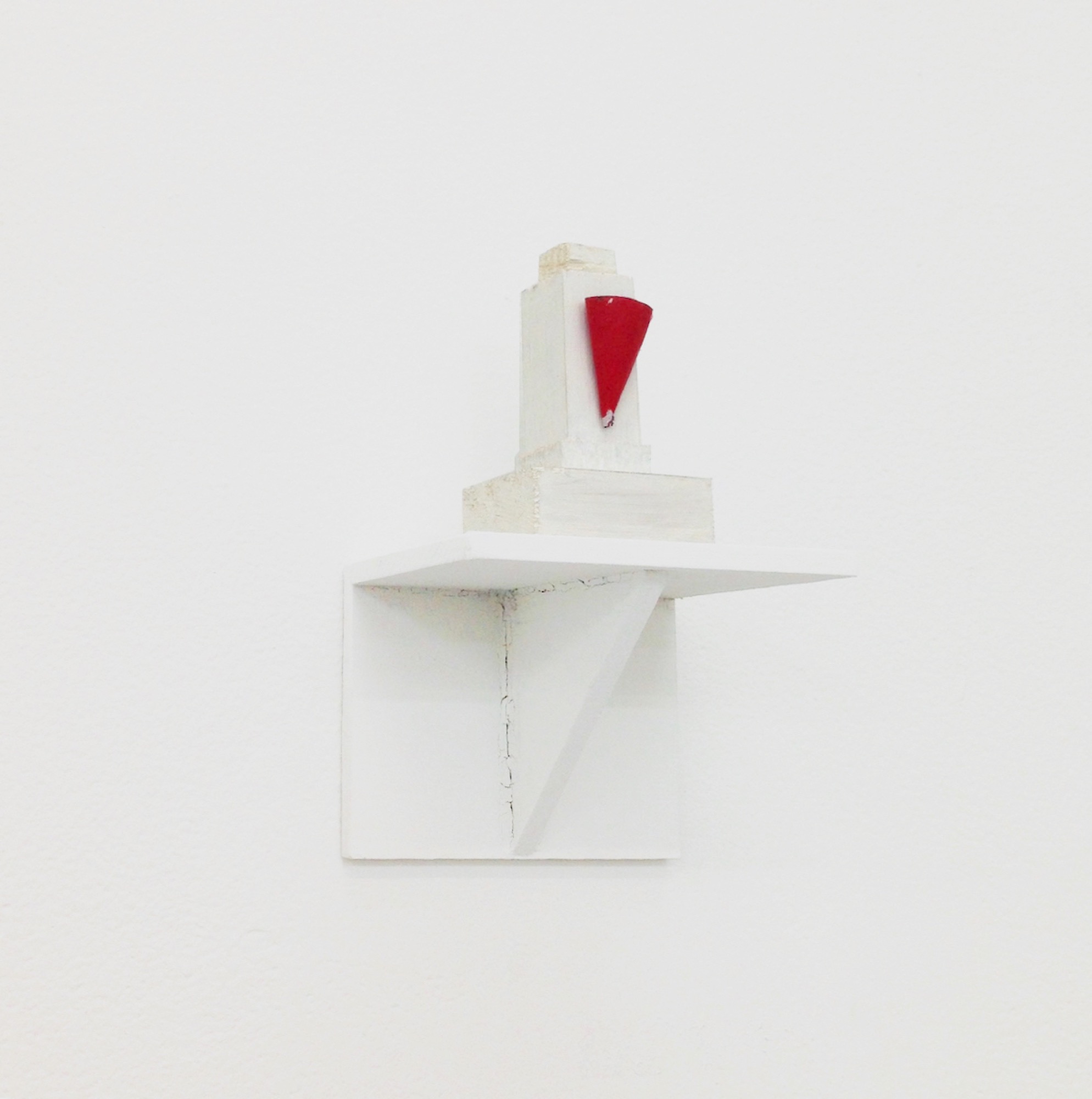

And stepping back further in time, we have Sam Cranstoun's Untitled (Nicholas and Alexandra), 2017, a small oil on board rendering of a scene from the obscure British film Nicholas and Alexander, depicting the life of the last ruling monarch of Russia, Tsar Nicholas II, who ended up being shot in a basement in the first year of the Revolution, and Alex Hobba's The Future Began on the Ruins, 2017, a large inkjet-printed cloth laid wrinkled and semi-legible on the floor of the gallery, with a design based on the only known documentary photograph of the basement in which the Romanov family was killed.

The show is called I can see Russia from here, put together by independent curator Chelsea Hopper, not coincidentally in time to mark the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

Of course, the Revolution is one of the test cases for the possibility of art to effect social change. The great avant-garde artists of Russian Constructivism and Suprematism like Malevich, Tatlin, Popova and Stepanova were precisely not left out by the leaders of the Revolution but were given a chance to provide the new government with its image, to imagine what a “proletkult” could be. And, needless to say, these artists' supremely abstract designs were seen in retrospect after the Revolution to already be expressing something of the spirit of Communism. Avant-garde art appeared to be accorded a positive stake in actual political power in a way rarely if ever seen before or after. The first years of Lenin's Bolshevik government seemed to fulfil all artists' secret ambition to have society be the way they imagine it, for art to provide the model for an entire way of living.

How did it all turn out? By the time of Stalin, Malevich was painting tractors and peasants and using his famed black square as an artist signature, a tiny and necessarily discreet act of rebellion against the dictator's tyranny. But then it has even been argued by the Russian dissident art historian Boris Groys that the Russian avant-garde was already in a way Stalinist, that the very project of remaking society in the image of art is itself totalitarian.

And how does the Revolution and its hopes for art stand 100 years later? What ambitions are there for a liberatory, emancipatory, let alone revolutionary, art in 2017? What socially transformative potential, if any, is art still thought capable of embodying today?

Let us take perhaps the key work in the exhibition: Nixon's Black and Brown Cross, with its four black enamel squares painted into each of the corners of a thin plywood sheet. It's about the simplest possible way—much like Malevich's Black Square of 1913, which Nixon has also recreated many times—of making the work of art distinct from its surrounding space. What we have with those four painted squares is just the slightest separation of the work of art from the materials out of which it is made: after they have been applied, the plywood is no longer merely plywood (And it is an extraordinary coincidence that 1913, the year Malevich made his Black Square, was also the year of Duchamp's first readymade, which similarly is about that minimal gap separating the art work and the space it occupies.)

And generalising Nixon's work a little, it is perhaps this task that it fulfils throughout—introducing a gap not so much between the work of art and artistic space as between the work of art and social space (although the two are not strictly to be separated).

But what exactly do we mean by this? At the university at which I teach, two PhD students' theses involve the work of Nixon. One is a history of the avant-garde music scene in Melbourne from the 1980s on, in which Nixon's absolutely unskilled low-fi noise collaborations can be understood to mark a particular moment. The other is an extended account of the continued relevance of and artistic thinking behind the important exhibition Recession Art and Other Strategies, held at Brisbane's Institute of Modern Art in 1985.

In both cases, there is little point in aestheticising let alone formally examining Nixon's work. It is deliberately lacking not only in skill but virtually in any visual or aural interest. But it does allow us to mark or record—almost indexically—a certain artistic, but let us say more generally social, scene. It functions like a memorial, almost a gravestone, around which it can be seen to gather. It allows us to put together and give a collective identity to a series of microscopic, almost indiscernible, moments and perceptions so that they can be remembered and later studied. It stops the endless, chaotic flux of passing events, so that they can be assembled and given a name. To put it in a more recognisable language, it creates a “scene”.

On the night of the opening of I can see Russia from here, some 20 to 30 people gathered across the two gallery spaces of TCB. Most seemed to know each other. They had either brought some friends along or met unexpected others they already knew. They stood together around the art, which was not much more than the occasion for this gathering. There was a momentary sense of community, of sensus communis, brought about by the art, but it was not itself higher, any more “transcendental”, than the people standing in the room. The work was almost like its shadow, its reflection, its recording. It was merely the name or image for this gathering, were it to be remarked or remembered some years into the future.

Was it in this way that we saw Russia that evening, and that the art embodied something of the spirit of Communism as a form of the radical equality of people and their experiences?

There is currently a Nixon retrospective on at Castlemaine Art Museum and later this year Heide Museum of Modern Art is going to put on a survey—along the lines of previous ones involving Cubism and Minimalism—on Constructivism in Australian art. But it is simply astounding—although in another way entirely predictable—that no major institution in Australia has seen fit to put on an exhibition marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution, one of the signal events of human history and opening up an era probably only brought to an end by 9/11.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.

Title image: Sam Cranstoun, Untitled (Nicholas and Alexandra), 2017, oil on board.