HTTP.PARADISE

Hester Lyon

The internet is both pluralistic and policed. From this premise, HTTP.PARADISE speculates on the terms of digital paradise through radical perspectives in video art, the moving image, music videos and video gaming. Curated by Jake Treacy and presented online via Incinerator Gallery, the exhibition is a direct response to cancelled artistic opportunities and physical distancing, positing the digital as a space to explore contemporary politics, autonomy, spirituality and identity. The exhibition’s composite title, HTTP.PARADISE, prefaces the search for paradise online as one marred by antithetical and incompatible personal and societal states of being. As such, the exhibition presents a series of video works that engage digital technologies to confront the very question of how the virtual, as a pervasive lens through which we navigate the world, defines identities and justifies disempowerment.

In the wake of a global health crisis, there is a literal disconnect between the gallery, the artwork, the artist and the audience. Consequently, the exhibition cannot be considered without a discussion of the interface—the screen that now sits between the audience and the exhibition. On the one hand, the current institutionalisation of the screen feels like a coping mechanism for the artworld’s losses: the audience defined by proximity, the comfortability of objects in space, the illusion of professional security. On the other hand, the digital emerges as a disruptive force to imagine alternate connectivity and disrupt power structures outside of, and in opposition to, the institution. HTTP.PARADISE does both, offering a double speculation of the future: a speculation of the nature of collectivity in a world connected solely through virtual means and a speculation of the future of exhibitions themselves.

In their commentary on histories of representation and political negligence, Angela Tiatia and Hannah Brontë’s opening works establish the realities of contemporary culture from which the subsequent videos in HTTP.PARADISE speculate more radically.

Angela Tiatia’s work Interference (2018) is an onslaught of imagery, cascading hard and fast through the screen in a deliberately concise 1 minute and 6 seconds video. Originally commissioned as a response to dancer and choreographer Amrita Hepi’s A Caltex Spectrum—a finalist in the 2018 Keir Choreographic Awards—Interference borrows Hepi’s rhythmic choreography and pulsating beep, presenting three performers visually filtered through a black and white effect. An aspirational score faults into glitches and alerts, before analogue TV static consumes the screen, making way for a suite of rotating stock images. Periodically and rhythmically, a slideshow of culturally defining images referencing pop culture, Hollywood, celebrity, cinema, politics and advertising flash before us. These images become symbolic of the structures that prefigure identities in order to disempower them. While the performers in Tiatia’s work momentarily transcend race and identity through visual effect, the artist reminds us of the barrage of external influences that disable a paradise beyond history, politics and self. Interference also argues towards the notion of paradise as inextricable from the colonial project. As a Pacific Islander artist, the exoticisation and commercialisation of Tiatia’s home is a violent and ironic imagining of paradise defined by the outsider. As some of the poorest nations in the world, the natural beauty deemed paradisiacal of the Pacific Islands is literally being washed away by the devastating effects of global climate change.

Hannah Brontë, an artist of Wakka Wakka, Yaegl and Welsh bloodlines, further explores the effects of climate catastrophe in her work tellus terra (2020), positing First Nations knowledge as central to managing the exhaustion of natural resources under the negligence of patriarchal capitalism. Made in response to the devastating 2019/20 bushfire season, Brontë presents a series of portraits of women and children connected to the land as traditional owners or close visitors to position generational knowledge and maternal power as the only solutions to the current state of ecological disaster. In the context of Brontë’s previous video work, and the intensity of digital imagery throughout HTTP.PARADISE, tellus terra lacks a conscious interrogation of the digital medium. It is in this work only that the screen feels like an intermediary, disarming the work’s impact as the viewer is distracted by panning and fading photographic slides.

A consideration of the terms of mediation is amplified in both Mohamed Chamas and Louise Terra and Rachel Feery’s videos. These works force us to abandon the mediation paradigm, where the dread of distraction and filtered experience is argued in relation to the live event. As an online exhibition, HTTP.PARADISE is not an afterlife or secondary to a physical exhibition; therefore, we must acknowledge the unique capabilities of video to mutate across display contexts. Originally intended to be experienced as virtual reality, both Chamas and Terra and Feery’s works exist in this exhibition as a recording of a VR experience and an interactive 360-degree video respectively. As these formats dissolve the access barrier between the work and its audience, losing some of their distinctive immersive quality, their transcribed presentation re-temporalises the viewing experience: no longer must audiences book an appointment, wait in line and commit to wearing a headset. As bootlegs of their original versions, these works provoke the hierarchies of access found in physical institutional contexts by democratising their means of distribution.

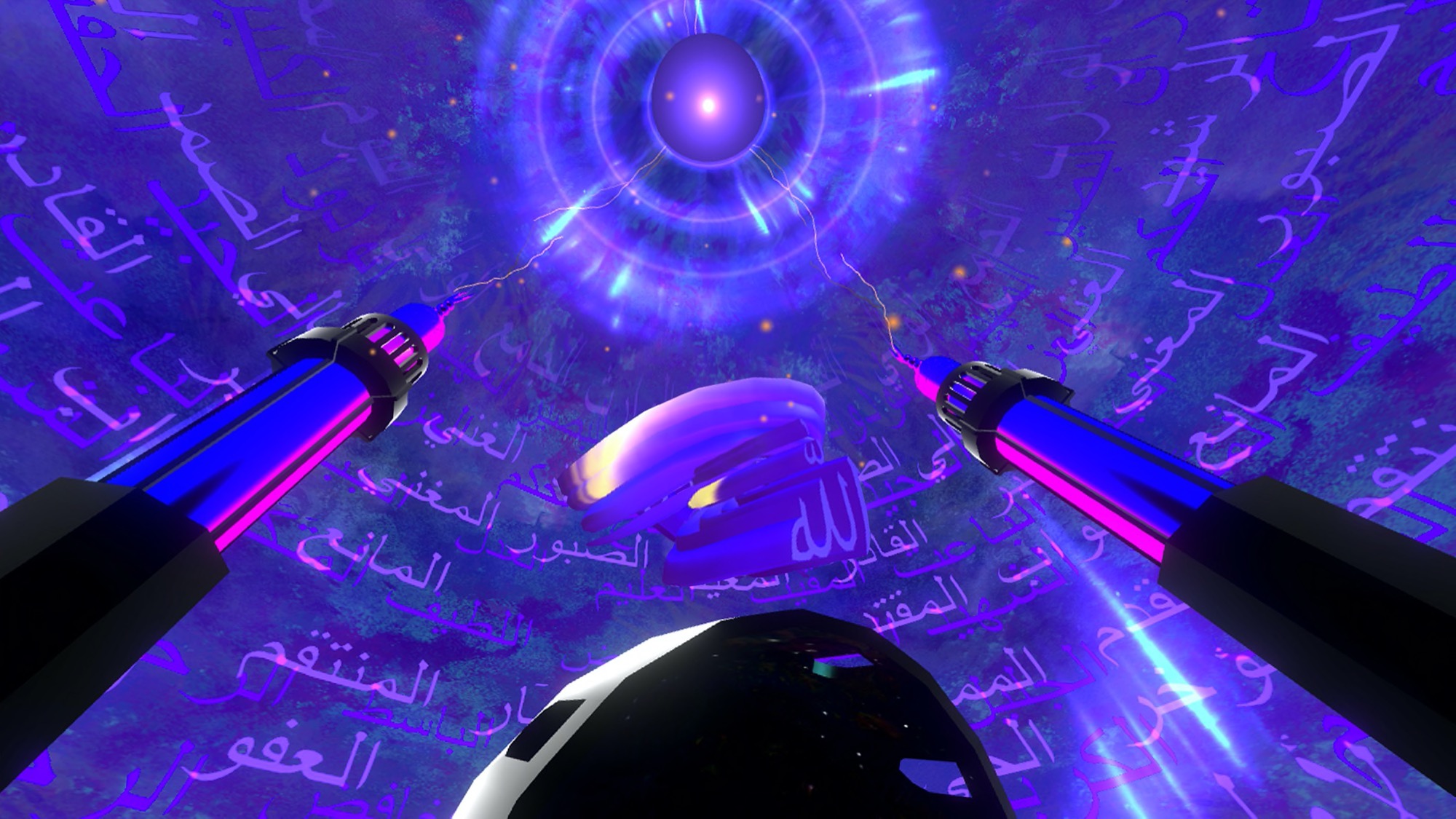

Mohamed Chamas’ سايبر تصوف (cyber tasawwuf) (2018) explores the Sufi meditation known as Lataif-e-Sitta (the six subtleties) to construct a series of virtual architectures. In a disorientating journey, the viewer’s floating body is contextualised in six energy centres. Through a glitch aesthetic, witty cultural references and the virtual dizziness, سايبر تصوف (cyber tasawwuf) proposes how the spirit may transcend the politicised body through a mystical, digital and psycho-spiritual exploration of self. As a semi-autobiographical exploration, Chamas interrogates Western constructions of the “Muslim” body by directly engaging with media through which the other is defined and marginalised. Chamas deliberately uses technology to subvert these power hierarchies, particularly the specificities of VR, a technology originally conceived for military use and, ultimately, the suppression of the very belief system Chamas explores.

Musician Louise Terra and visual artist and film-maker Rachel Feery’s music video Nature Calling (2019) expands upon the duality of the real and virtual selves through a sci-fi narrative of survival. An armoured Terra assumes the avatar, moving through a series of arid, Mars-like landscapes collecting tokens of lifeforce and sustenance. To survive, Terra must confront the “imposter”, a ghost like image of herself. The video’s 360-degree navigation means we can never consume the entire environment or narrative at any one time. Whilst this could feel like a disservice to the original VR experience, it works to amplify Terra’s duplication of the self. The dystopic digital realm forces a confrontation with multiple truths and psychological slippages as a means of survival.

In opposition to Terra and Feery’s arid otherworld, Youjia Lu’s Super(im)position: enduring (non-place) (2018) returns to the intimacy of domestic space to explore the liminality of self. Lu’s work is an important touchstone in HTTP.PARADISE, tying together the recurring themes of multiplicity and non-place. In a projection set against hanging blinds within a dark living room, Lu experiments with superimposition techniques where intercut layers of light at rapid pace are perceived as constant, exploring void or non-existing spaces as generative of change. An awareness of the screen and its framing device is pertinent in viewing Lu’s work. There are three layers of framing: the screen of our own monitor, the embedded Vimeo video and the projection. As we view the work we must slip between these layers, contemplating our own self-consciousness at each level of consumption as we enter Lu’s domestic space through our own domestic space. We are reminded that the mechanics of the work’s production mimic the mode of its display and the method of the audience’s consumption.

Felix ter Hedde and Hannah Hotker’s sicksickcitizen (2019) shamelessly admits this mimicry. A tour of contemporary capitalism and consumerism, the video’s avatar “jane66citizen” moves through a series of worlds that become increasingly removed from reality: a cinema, sex museum, Starbucks, alleyway, bloodied warehouse, outer space. The scenes do not create an interconnected landscape but rather flick into one another as “jane66citizen” hits a wall or boundary. An omniscient, automated narrator repeats the phrase “you are not crazy, and what you are experiencing is real.” The narrator comforts our concerns for less screen time, suggesting we accept that the internet and our existence cannot be separated. The seamless interconnection of real and imagined worlds forces us to reflect on how we differentiate between the virtual and the physical, escape and paradise, art and culture. With the omnipresence of the internet, it is increasingly difficult to differentiate between art and mass culture and HTTP.PARADISE consciously positions each video as existing within a broader social and political landscape. In sicksickcitizen, ter Hedde and Hotker argue for the internalisation of the screen as a coping mechanism for the inability to decipher.

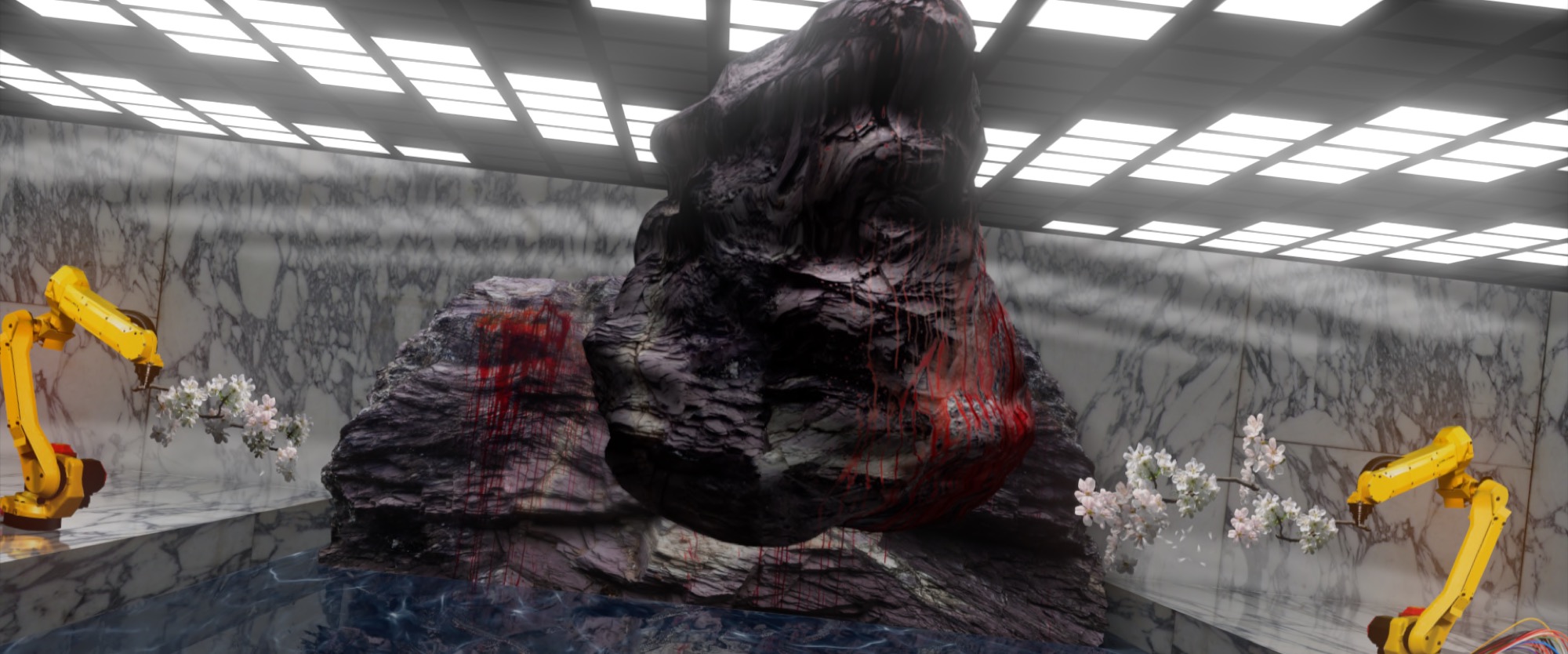

The final three music videos featured in HTTP.PARADISE exemplify this dissolution of cultural distinctions. Two collaborative music videos by visual artist Tristan Jalleh and musician Corin Ileto are crescendos of violence, disruption and nightmare. The idea of paradise has been shattered and the future is imagined by a dystopian/cyberpunk/cyborg aesthetic. In contrast, visual artist Patrick Hase and sound artist Bridget Chappell’s Yubaba (2019) is a euphoric conclusion to the exhibition, leaving us with an elusive paradise defined through nostalgia and retrospect. An homage to the aesthetics of internet 1.0 and the anarchy of rave culture, Chappell and Hase lament the loss of digital escapism, reminding us that paradise is ultimately ungraspable as we cannot perceive the present from within it.

Of all the online exhibitions that have emerged over the last few months, HTTP.PARADISE excels in allowing the audience to feel no loss viewing artworks from a laptop and in their home. The original intention of the works in HTTP.PARADISE—to exist virtually—is not disrupted by the screen, ultimately building a compelling case to continue autonomous engagement with digital works in online contexts.

Importantly, HTTP.PARADISE makes some attempt to maintain the logic of exhibition time—finite exhibition dates, an intuitive curatorial path—to reassure the audience that we have not lost all the comforts of traditional exhibition formats. As a result, the videos maintain their status as art objects and lose some of their claims to political provocation, for they are not entirely public files, ready for download, sharing and reproduction. Their ambition to employ digital technologies as a means to radicalise virtual communities is ultimately shielded from the crude processes of de-contextualisation and shared authorship that are the lifeblood of the internet. Unlike the conditional, institutional spaces of a gallery, there is an expectation that, online, publics can freely contribute, intervene and reproduce cultural material. If HTTP.PARADISE asks us to collectively imagine alternate visions for the future, perhaps it could have invited a live feedback-loop of commenting, sharing and tagging to literally expose how an artwork changes, erodes and expands as its social, political and institutional frameworks shift. Or perhaps this is asking too much.

Hester Lyon is a writer and arts worker based in Melbourne.