Hoda Afshar, The Fold (2023)

Paris Lettau

It is often said that our contemporary culture is saturated with images. However, it is also true that most images remain unseen. In fact, it could be argued that contemporary culture is saturated with unseen images struggling for visibility, to be seen. But what does it mean to “be seen” today?

A common answer to this question is that we are seen when we are represented and visible to others. But this answer risks confusing mere observation with recognition. When merely observed by another, one is reduced to being an object of the other’s gaze. (Just go to a contemporary art exhibition to experience the discomfort of the gaze of others.) Far from a neutral acknowledgment of one’s existence, this process of objectification ensnares us in the observer’s perceptions—and potentially their fantasies and delusions.

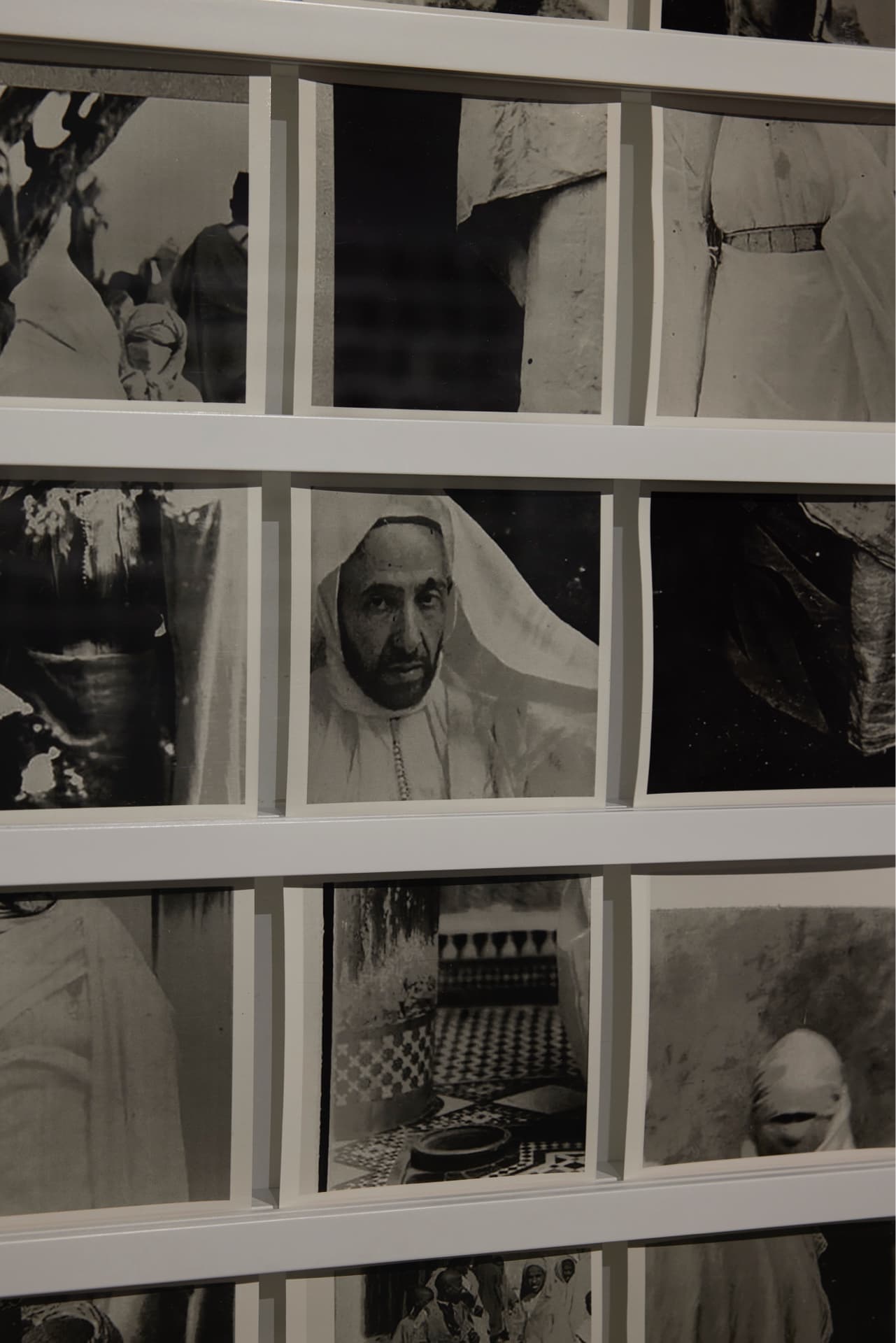

These fantasies and delusions were a topic of great interest to Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault (1872–1934), the subject of Hoda Afshar’s newly commissioned work The Fold (2023). Clérambault was a French psychiatrist who took thousands of photographs of veiled Islamic women and men when serving as the head of the psychiatric service of the French colonial army following the establishment of the French Protectorate in Morocco in 1912. Afshar has collated hundreds of these photographs, which are held by the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, and presented them in an immense grid of Polaroid-like snapshots.

In an obvious way, Clérambault reduces his subjects to mere objects. One could imagine Clérambault today sharing his photographs on his own Instagram account and the Moroccan women and men responding to the images through their own Instagram accounts—some positively; some negatively.

Social media is one way we take ownership over the objectifying gaze of others and “master” ourselves and the world we engage with. Digital gestures—liking, sharing, or commenting on photos and posts—reflect how we see ourselves and aspire to be seen by others. To “be seen” in this sense means to recognise ourselves in the content we create and engage with and to be mutually recognised by that content and those who engage with it.

Afshar presents a version of this form of mastery in a twenty-six-minute panorama projection featuring five commentators—Danny Sullivan, Santilla Chingaipe, Justin Clemens, Andrea Eckersley, and Virginie Rey. Each commentator delivers a monologue to (and in a sense against) the objectifying gaze of Afshar’s own camera. Afshar films the commentators in a mirror room. Faced with an infinite reflection of their own image, the commentators attempt to explain the true significance of Clérambault photographs.

Yet every attempt to master the photographs is answered and doubled by the commentator’s own reflection in an infinitely collapsing slippage of self-misrecognition, as though each lives a version of Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich (1999). They appear to be speaking to the abyss of their own incredulous image, which they find impossible to recognise and which likewise refuses to recognise them. The usually loquacious philosopher Justin Clemens develops a nervous vocal fry as he awkwardly gesticulates to his own image, which of course does the exact same thing right back at him.

One commentator argues that Clérambault’s photographs are quintessential examples of the colonial gaze’s voyeuristic intrusion onto unconsenting colonial subjects; another argues they are not voyeuristic images at all but cold, impersonal, and scientific; another claims that Clérambault’s obsession with the veiled bodies of his Moroccan subjects could originate from the trauma of the funerary covering of the body of his sister, who tragically died when Clérambault was a child.

Afshar’s video work suggests that all these attempts to master Clérambault’s photographs are just projections of the commentator’s own self-image, as though they really seek to recognise and master themselves through the photographs.

This has the peculiar effect of quarantining the mirror room of self-projecting commentary at a safe distance from the photographs, which are presented on the other side of the room. It’s as though the photographs are just left there out in the open for us to see—and they are well worth seeing.