Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line

Nikita Holcombe

It is a relief to find that Hoda Afshar’s first major Australian survey exhibition, Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line (2023), is housed in the contemporary galleries in the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s South Building, and not Sydney Modern. While entangled and bound up with associations of the “white cube,” here, the works do not face competition with their architectural surroundings. Curated by Senior Curator of Contemporary Australian Art, Isobel Parker Philip, the entrance to the exhibition is a black-and-white wall-to-ceiling print of Afshar’s work from the series In turn (2023), in which three women are captured in a moment of intimacy—braiding hair—demanding that this show is not easily missed.

To simply say that the Iranian-born, Naarm-based artist’s artworks are impactful is a gross understatement. Instead, it would be more appropriate to say that they pull you in, hold your gaze, and force acknowledgement of egregious acts that are and have been quarantined by governmental forces. There is a photojournalistic approach to Afshar’s photographs—they gracefully straddle documentary photography and artistic expression. Such strong works require a gentle, yet robust curation, which is certainly evident here in its clear thematic address of difficult narratives. The considered exhibition has alluring, beautiful aesthetics informed by soft lighting and distinct wall hues that induce a deep sense of reflection and contemplation. The exhibition title, A Curve is a Broken Line, is derived from a poem by Iranian-American writer Kaveh Akbar, which, as the exhibition suggests, speaks to “an admission of vulnerability but also strength.”

The mapping of the exhibition is guided by distinct series and bodies of works, marked by contrasting wall colours, and defining titles and wall texts. The movement from one room to the next feels seamless, there is no naff or failed attempts at linkage in sight—a product also of Afshar’s artistic consistency and ongoing development. The distinct frames and hang for each section simply add to the cohesion.

The works encased in the first room, titled “In the exodus, I love you more,” are various sizes, often layered, and sometimes overlapping. This is an obvious departure from the typical “white cube” gallery hang. Here, the photographs are set at different heights. This space holds remnants of Afshar’s presentation in this year’s The National: Australian Art Now (2023) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Aura (2020–23), in which black-and-white photographs printed on PhotoTex and board were perfunctorily layered such that they sheathed the interior architectural structure. This presentation was initially influenced by the 1955 travelling photography exhibition The Family of Man, first presented at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, curated by Edward Steichen. The flat pack styled exhibition consisted of over five hundred photographs from sixty-eight countries and was a photo essay on the human experience post-World War II and toured internationally for eight years, including to Naarm, and Afshar’s birthplace, Tehran.

In this first room, the walls are coated in a grainy cream hue, not dissimilar to the colour of the Iranian sand captured in some of the photographs. The hang generates the visual experience of a photo essay; so too does the lack of detailed wall labels. As I look at the images—women in stylish, bug-eyed sunglasses, a fog-drenched landscape with only just discernible figures—I find myself wishing I knew who and what I was looking at. But at times I question whether it is my prerogative to know, or if their visibility within the space is enough. Despite the anonymity contrived between viewer and subject, an acute intimacy can be detected between Afshar and her subject, one that appears founded on transparency and trust. This can be seen in the subject’s unguarded, relaxed posture, soft stance and acquiescent gaze.

Afshar interrogates the poetics of memory. The next, blue room, titled “In turn,” is soft, gentle, and deeply considered (the same can be said for the whole survey). In this room, the photographs are not engulfed by the gallery structure but are lifted, carried by white frames on the blue walls. This space holds Afshar’s new body of work, In turn (2023), made in response to the feminist uprising in Iran in September 2022. The opening of this exhibition marks one year since the murder of the twenty-two-year-old Jina Mahsa Amini, who was arrested by Iran’s morality police for not wearing the hijab properly. The photographs capture Australian-based Iranian women dressed head-to-toe in black, outside, embracing, or braiding each other’s hair. This response to an event that was undeniably violent is anything but. Instead, it acts as a pause, a moment of stillness and reflection. The collection of photographs is analogous to a temporary memorial or monument to Amini—and distill the collective nature of grief. It is important to note that while Afshar’s work is a pause, the violence is yet to cease.

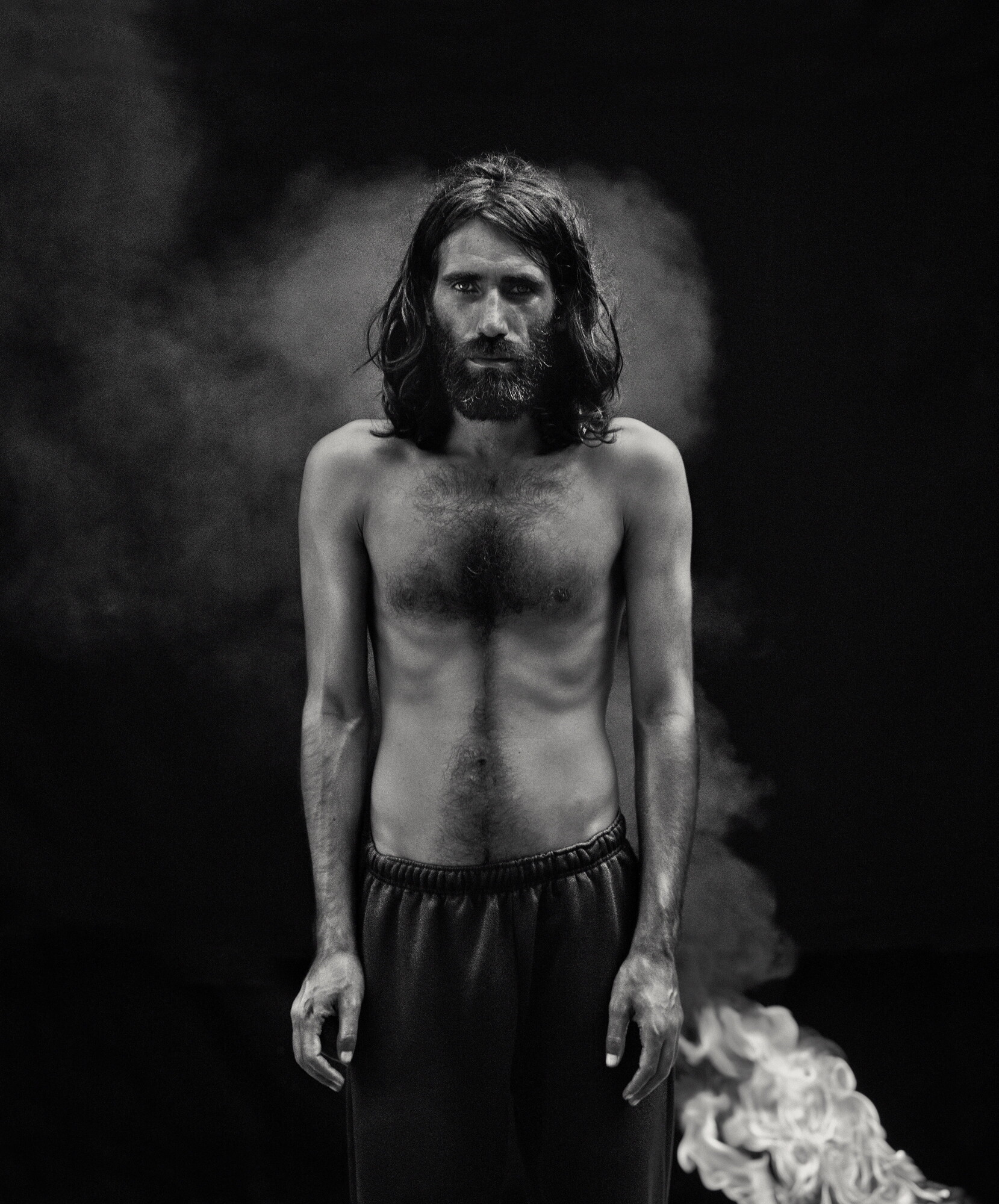

While the works themselves are visually poetic, Afshar refuses to dilute the narratives she addresses. In the following rooms is the photographic series “Remain,” which centres on those who have suffered in the Manus Island detention centres as a result of Australia’s draconian immigration policies. Each black-and-white portrait captures moments of movement; there is a restlessness emanating from the men being kept in captivity. Some peer directly down the camera’s lens, while other figures are obscured by swathes of sand. The individual titles of these 2018 works are the names of Afshar’s subjects: Edris, Ibrahim Mahjid, Emad Moradi, Ramsiyar, Behrouz Boochani, Mohammad, Shamindan and Ramisiyar, Ari Sirwan, and Thanus. Through this process of visibility and naming, Afshar dignifies their humanity and agency and claims agency in their narration to the Australian public. This couldn’t be further from the way asylum seekers were portrayed in the media during my upbringing under the Howard Government (1996–2007): terrorists, unsafe, self-entitled, and gorging on “Australian” resources. It is through the subversion of the camera’s lens—the roots of the medium steeped in imperial forces and held by colonial forces to dictate narratives, such as was the case in Australia—that these figures reclaim their identity.

At the same time as learning who these individuals are, voices can be heard reverberating through the wall from the adjoining room. Here lives the two-channel video work Remain (2018). In this video, the camera follows a series of male detainees of Manus Island Detention Centre (in Papua New Guinea), some of whom I had just encountered in the other room. The men are mostly walking and talking, framed by dense, flourishing jungle or picturesque sandy beaches. As they move, the men share first-person accounts of mistreatment and torturous conditions, the lack of medical care, and list friends who have died by suicide. There is no voiceover in the video, instead the men are granted an opportunity to speak for themselves. The viewers hear them speaking in their first languages as they read English subtitles—absorbing narratives that can no longer be refuted.

The artistic techniques used in Remain (and Afshar’s practice more broadly)—that is, pairing soft, beautiful imagery with difficult, violent accounts—arise in French theorist Jacques Rancière and his notion of “the intolerable image.” Exemplary of this kind of image, for Rancière, is the work of the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar and his artworks that communicated the horrors of the Rwandan genocide in 1995. They utilised subversive artistic techniques, including the rejection of graphic imagery and instead privileged first-hand accounts and text, to not inflict harm on the viewer and instead illicit a sense of empathy. Just as Jaar aimed to disseminate news of the Rwandan genocide to the world, Afshar poetically frames her own and collective experiences of Iranian women, refugees, and those attempting to speak out against injustices. As noted in the exhibition text, “Afshar doesn’t simply alert us to injustice, she compels us to care.”

The next room houses a series of photographs titled “Behold,” which embodies a distinct painterly sensibility. The images are soft and silky; while they are not erotic, they do evoke a keen sense of intimacy. The figures captured are anonymous gay men who invited Afshar to a bathhouse in an undisclosed Iranian city. A few of the men peer into the lens, others are entangled in embrace. While these men anticipate persecution for who they are, isolated to expression in Iranian bathhouses, here they comfortably assume visibility.

To its right is a white room titled “Agonistes.” Here, a large single-channel video work projects snippets of faces and figures. The video flicks between various whistleblowers whilst the camera angles obscure their faces, making them almost impossible to identify. The individuals provide first-hand accounts of wrongdoing by the Australian government and institutions, including mistreatment of detainees on Manus Island and corruption within the Australian Force in Afghanistan. On adjoining walls are portraits constructed by a process of 360-degree scanning, 3D printing technology, and photography. The resulting portraits have a ghostly presence, the white busts hover and feel dislocated from their black background. Each portrait is merely a shell of the person they represent, with no clearly discernible features, possibly a consequence of exposure and poking holes in the carefully constructed image of the Australian nation-state. Accompanying the portraits are short texts that outline the issues these individuals raised and details of their consequent persecution. Through reading the text, what becomes startling is that these people were not protected by The Whistleblower Act.

The considered presentation acts in stark contrast to the celebratory attitudes towards Australia’s most famous whistleblower, Julian Assange (who received a Sydney Peace Foundation’s gold medal for his efforts). This is most likely due to his exposure of extreme wrongdoing by other nations, including the United States, and not Australia. Assange now has Barnaby Joyce, among others, lobbying for his freedom from a United Kingdom prison. The disparate treatment of calling out horrific treatment from internal and external perspectives certainly conjures a sense of great unease. The work prompts the questions: Is the gallery is a space to move around/deviate from these laws? Or a means to circumvent the news cycle? Or is the work just an indication that the gallery space isn’t considered to be serious in contrast with the law itself?

The final space, titled Speak the wind, returns to the hanging style seen in “In the exodus, I love you more,” this time with splashes of reds and frothing bodies of water glimpsed in the photographs. Here, Afshar looks to the invisible power of wind and those embodied in natural elements—drawing a parallel with the forces behind much of the abuse alluded to throughout the exhibition. A Curve is a Broken Line is deeply poetic, at times necessarily confrontational—and a show not to be missed.

Nikita Holcombe is a writer and curator based on Wangal land.