HELMUT NEWTON: In Focus

Cameron Hurst

Unlike most of the tedious PHOTO 2022 program, crammed with twee mises-en-scène and endless autobiographical snapshots, HELMUT NEWTON: In Focus is genuinely interesting. Newton is the blueprint for twentieth-century fashion photography: supermodels trussed by luxury commodities in hotel rooms or perfectly-formed nudes in industrial cityscapes, almost always in creamy monochrome. He is the master of producing sophisticated art images through harnessing commercial constraints. This modest but comprehensive exhibition, held at the Jewish Museum of Australia in St Kilda, shows a sizable selection of Newton’s silver gelatin prints interspersed with archival materials that tell the story of the photographer’s little-known years in Australia. The photographs are darkly erotic (sometimes to the point of kitsch). The social history component of the exhibition is fascinating—a twenty-year-old German-Jewish emigré shunted into a rural Victorian internment camp as an “enemy alien” becomes the preeminent photographer of the postwar Melbourne fashion industry, then promptly leaves. Who knew that every microblogger’s favourite fetishist started out as a Flinders Lane art bro?

Helmut Neustädter was born in Weimar Berlin in 1920 to a secular Jewish family who owned a button and buckle manufacturing company. Young Helmut apprenticed with the photographer Yva (no surname), who ran a successful studio creating avant-garde advertisements. But as anti-Semitism rose, staying in Europe became untenable. Nazis took over the Neustädter factory and after Kristallnacht, the family decided to flee. Helmut’s parents went to Chile. He ended up in British-controlled Singapore, where he lived for just under two years as the houseboy of Josette Fabian, a successful Belgian businesswoman who chauffered him around in her black Chevrolet. This sexy reprieve was not to last.

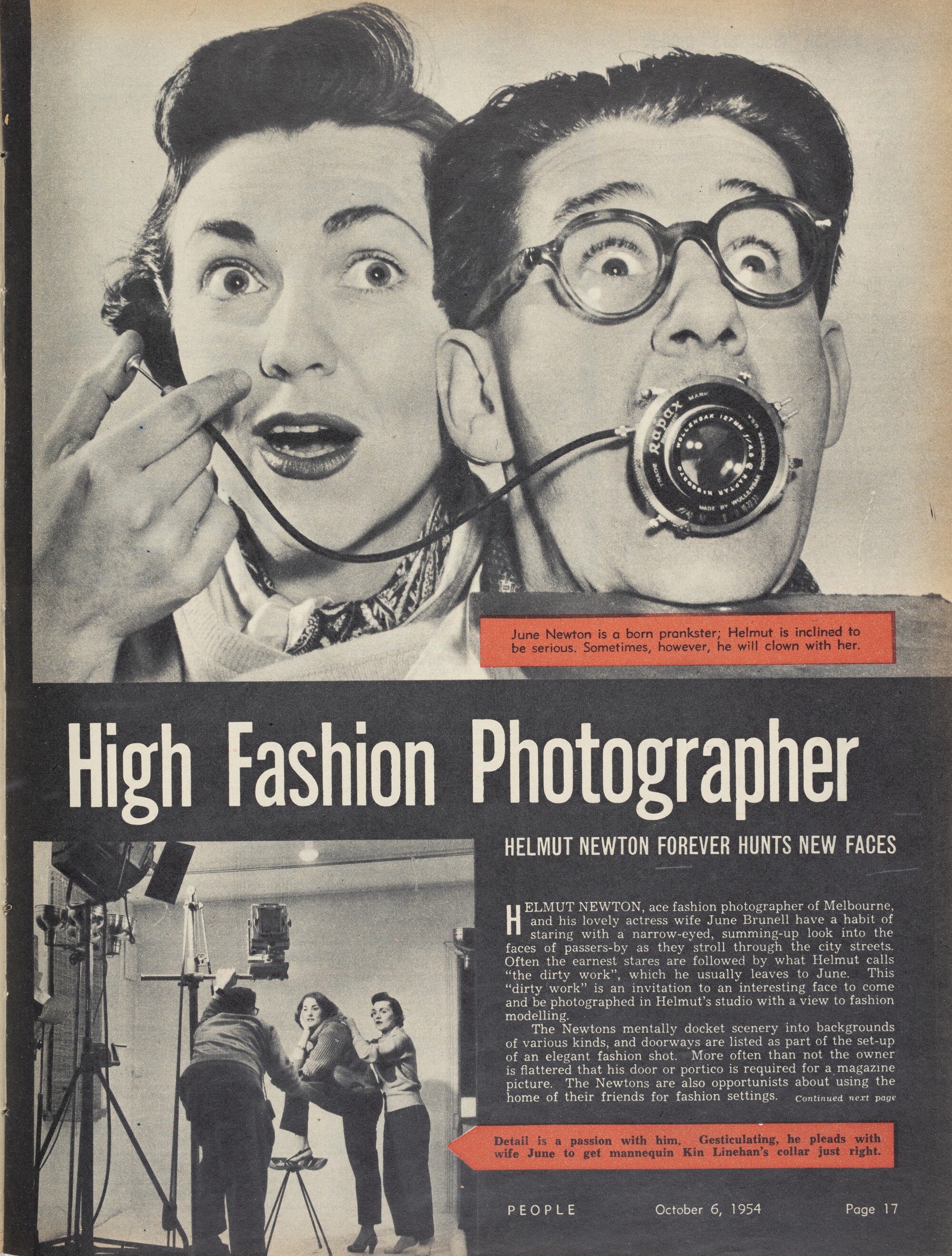

At the advent of war in 1940, the British government interned some twelve thousand refugees across the colonies who were perceived to be a potential threat to the Crown. Just under three hundred in Singapore, Helmut Nuestädter included, were shuffled onto the Queen Mary luxury liner and shipped off to Australia. After spending a year and a half cleaning latrines in a dustbowl Tatura internment camp—not particularly Weimar decadence nor fantasy of the Orient—Helmut served civil and military service before being discharged at the end of the war. He changed his surname to Newton and moved to Melbourne, where he met and married his life partner, the actress, model, shiksa and, later, photographer, June Browne. She also changed her name: to Alice Springs. Truly. The couple stayed in Australia on and off until 1961, when Newton’s international ascendence began.

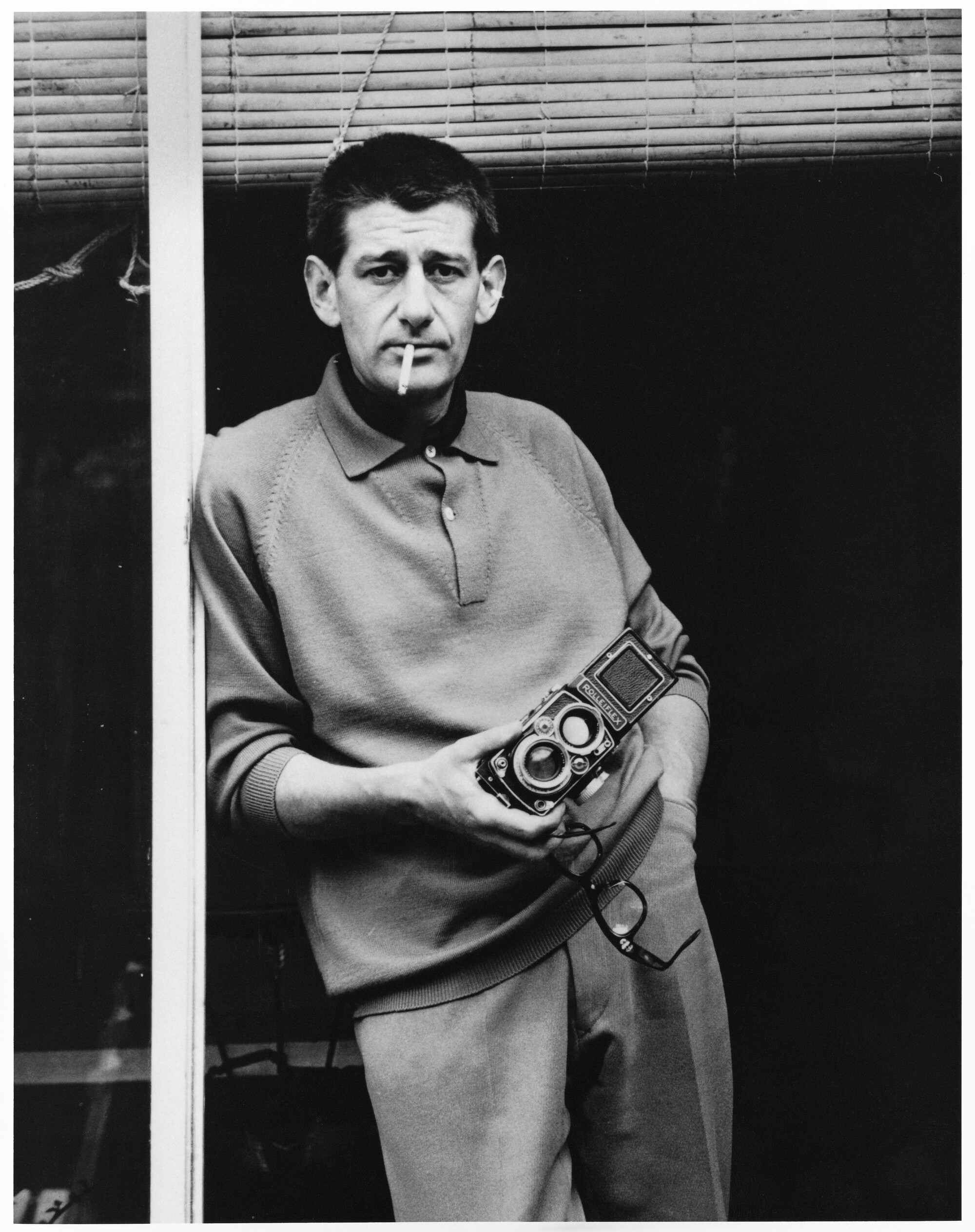

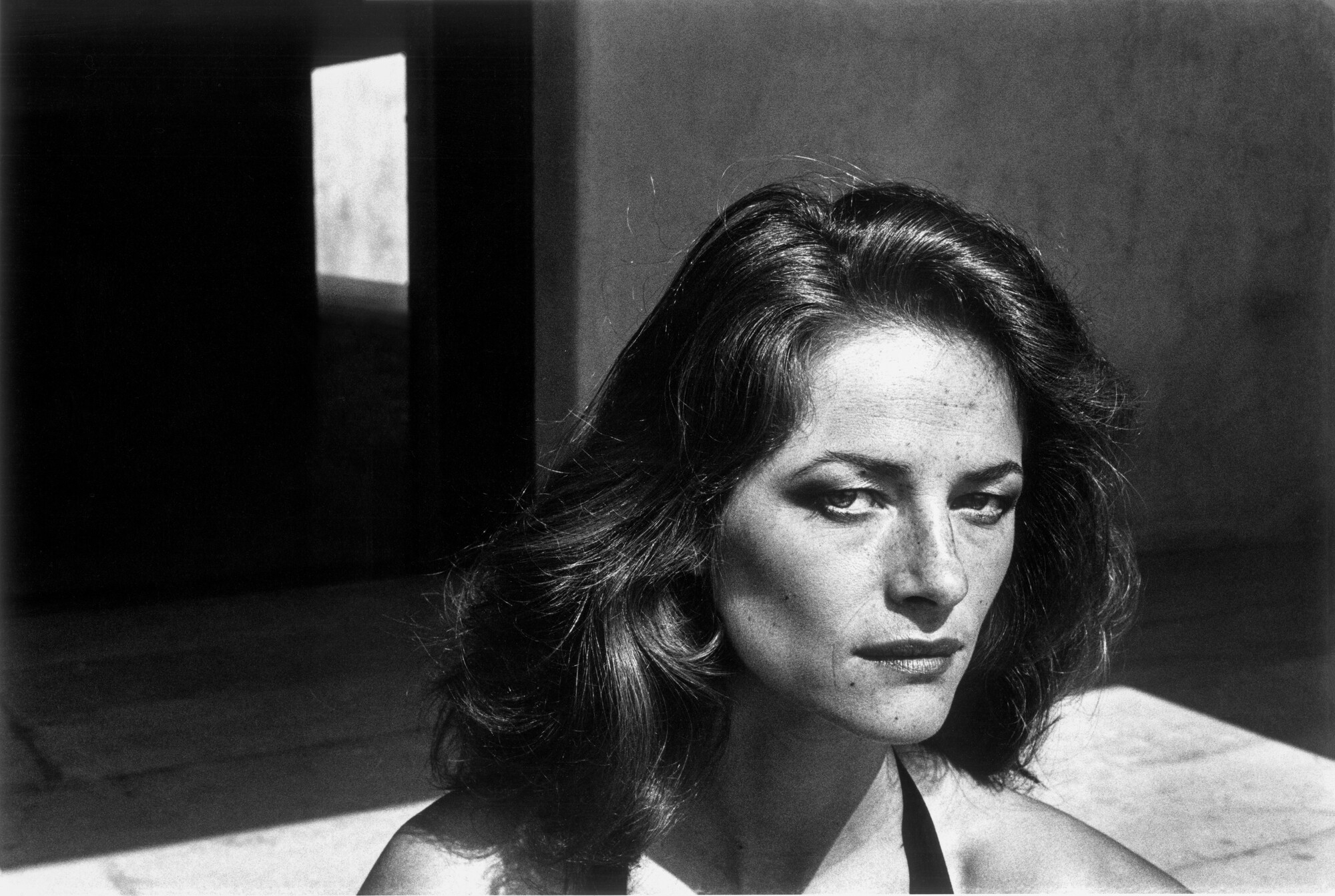

HELMET NEWTON: In Focus takes this provincial history as a starting point. The exhibition consists of a screening room on the first floor of the building and two connected rooms in a second-floor gallery space. Upstairs, material is displayed on scuffed concrete plinths and the floor is littered with chunks of concrete. This is allegedly to demonstrate Newton’s preference for shooting in gritty urban environments. A few unfortunate neon tubes, one circular, one wriggly, light the space. It’s best to ignore these immersive touches and get straight to the content. The first of the two gallery rooms features some classic photos—an exquisite Charlotte Rampling in profile, David Hockney as the protagonist of a meticulously composed piscine scene—alongside images by Yva and fantastic historical ephemera. See the Queen Mary luncheon menu card; newspaper clippings announcing the arrival of well-dressed internees; Newton’s 1942 Australian Army enlistment portrait; hilariously, a Farrago article reporting on the photographer’s first ever exhibition, at the University of Melbourne’s Rowden White Library … there’s transatlantic hope for the RMIT fashion school tragics yet. A friend told me that the owner of a hair salon beloved by the current Melbourne fashion cognoscenti said he hated the exhibition. A Newton superfan, he thought there was too much biographical junk, not enough focus on the pictures. “Why did I need to see his passport?” he complained. But this is a museum after all. As a dowdy art historian, I was enthralled by these paper traces of life in a city both foreign and familiar.

Visitors unimpressed by historical artefacts may not have found much to get excited about in the video on the ground floor. It’s a fairly low-rent compilation of clips that nonetheless provides valuable context to the exhibition. When I walk in, the camera is trained on Lesley Sharon Rosenthal, the author of Schmattes: Stories of Fabulous Frocks, Funky Fashion and Flinders Lane (published 2005, dedication: “For all those with a passion for fashion”). Rosenthal seems to know the life story of every person who sold a piece of fabric on Flinders Lane in the last century. She sketches a socially vibrant, prosperous milieu filled with migrants remaking a life after the horror of the war through the schmattes (rag) trade. Newton plied his photography services at the centre of this world, setting up a studio a block down from where Brunetti’s is now. More video segments cover similar content. An overview of the life of Newton’s Berlin mentor, Yva, is voiced by a relative of the latter who now lives in Melbourne. The invigilator tells me that many visitors to the exhibition shared personal connections to the photographer; it turns out my handsome Jewish boyfriend’s father was briefly Newton’s accountant. The first-hand report? “He was a lovely, lovely man”. This analysis is supported by a video interview with Kim Kelly, one of Newton’s Melbourne models. She recalls the photographer’s focus and professionalism and his growing desire to shoot erotic images outside the white-papered confines of the studio and, more broadly, conservative 1950s Melbourne.

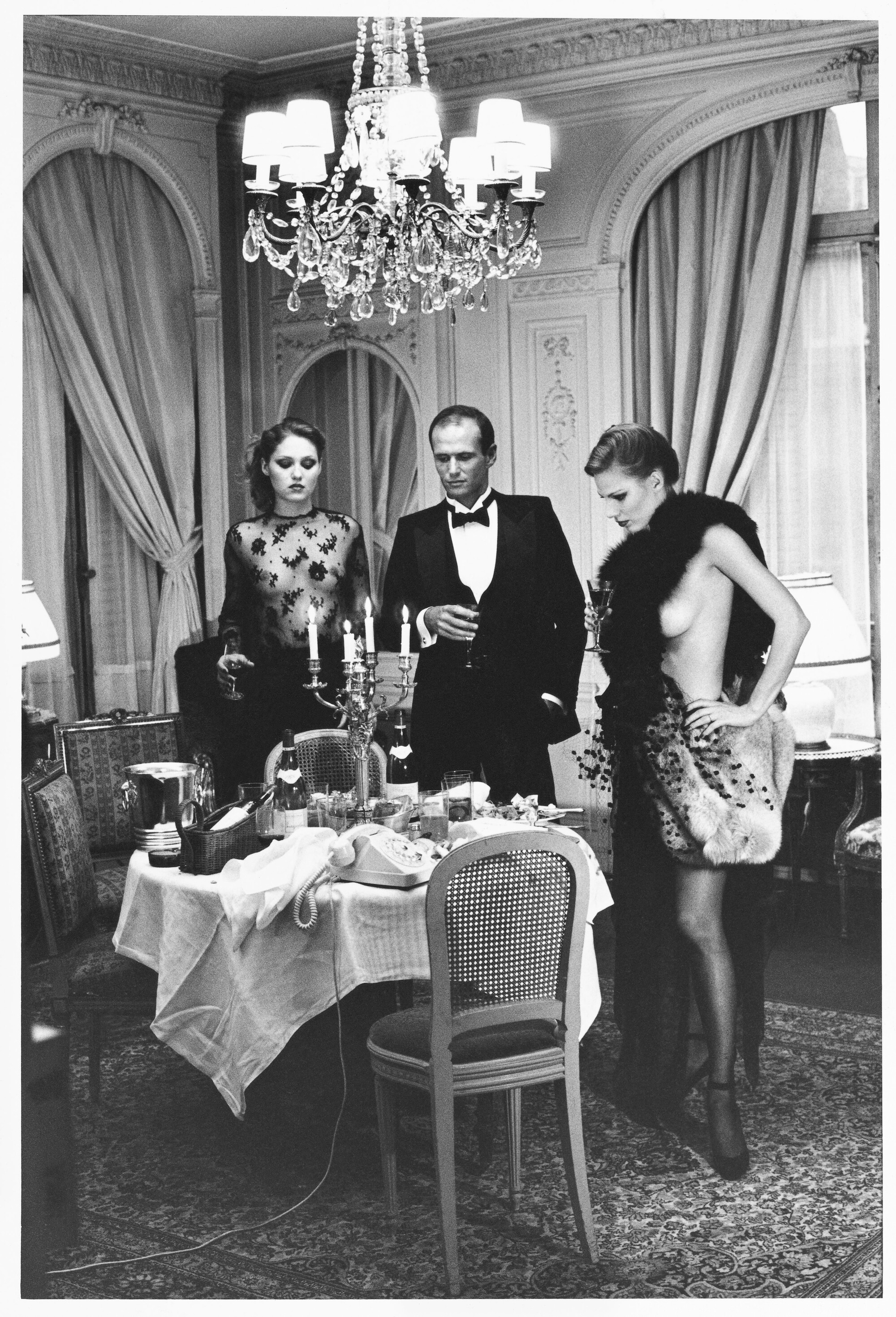

Ok, enough historical edging. Let’s get to the sex. Newton and Alice Springs departed the Antipodes in the early 1960s; the rest is in Vogue. For punters seeking the unadulterated Newton experience, the second room of the exhibition offers many a Veruschka (1975), Violetta (1979) or simple Nude in Seaweed (1976). The Paris images in the exhibition are by far and away the best. Nothing does more for androgyny and less for vaping than Newton’s iconic Yves Saint Laurent shoot for French Vogue, titled Woman into man (1979). A slicked-back model in a tuxedo leans towards a glamorous lover in a lobby hall, who swoons. The tips of their cigarettes just touch. Alternatively, see Upstairs at Maxim’s (1978), wherein a woman in a chic skirt suit receives a kiss on the slender wrist from a pomaded suitor. Her white hand is perfectly framed by the black velvet oval back of a chair. Looking closer, I notice that the hand has become detached from the woman’s sleeve and hovers mid-air, dismembered. A Surrealist riposte to cold romantic pieties? In the hotel room of After Dinner (1977), a Prussian industrial type with a receding hairline is flanked by two gorgeous women wrapped in varying configurations of nylon and fur. A chandelier exudes a dim glow. The trio stare wordlessly at a table stacked with empty wine bottles, napkins and plates of bones. A white telephone is angled conspicuously in the foreground of the image. Are they waiting for it to ring? If so, who could call? Have they already slept together or are they just about to? Newton’s photos are so satisfying because of this alchemical combination of compositional panache and narrative ambiguity.

A street in Collingwood I often walk down has a suite of PHOTO 2022 posters plastered up. The featured images are, quite frankly, awful. They show a series of women in grim houses, posing in varying states of stilted repose. One sits dead-eyed in front of a TV in a pussy-bow blouse and no pants. Another sinks into an armchair, staring at a bunch of berries strewn across her carpet. The most offensive image shows a woman bent at a forty-five-degree angle over a bathroom sink, applying lipstick in the mirror with her backside facing the camera. From afar, she looks like she might be nude. On closer inspection, the Weet-Bix-coloured stockings wrapping her legs become visible. A banana peel is mashed inexplicably on the countertop. What was the meaning of these images? I presumed representational empowerment stemming from some nominal truths of feminine experience: domestic spaces are banal, alienating and often dirty; some women are poor; not all women are thin and/or attractive. Is this really how women want to be photographed? It’s not for me.

Doing critical due diligence, I looked up the artist. Florence Babin-Beaudry, from Montreal. The series represents the trauma of miscarriage. Damn. Oops. The fruits symbolise foetuses. “Despite the fact that pregnancy loss is common, the silence around the phenomenon persists. It brings a grief that is often misunderstood and suffered in silence”, the online didactic explains. I feel a guilty pang of empathy and remember the dire current state of reproductive healthcare across the globe—Roe v. Wade on the out in the US, fire and brimstone Christian marketing executives in power in Australia (for today, at least). This subject matter speaks to urgent personal and political fights.

Yet there remains something cruel and tepidly ugly about these images of average women made to look even worse through the staged exaggeration of their most private lives. The symbolic fruit on the floor is painfully literal. The compositions are theatrically depressive. There is a noxious logic that the sheer moral rightness of depicting an important issue will accrue the photographic subjects representational dignity by default. A polemical review of the recent Whitney Biennial by the Manhattan Art Review critic Sean Tatol critiqued this position. “Just as a dramatic story doesn’t make a good novel”, Tatol writes, “a socially edifying moral doesn’t make a good artwork. A restaurant is good if the food is good, not because all the ingredients are organic or sustainably farmed”. Compare the aforementioned buttocks with Newton’s compulsive deification of black stockinged legs. Babin-Beaudry’s street posters are just as fetishistic, but take a dourly contrived set-up of women’s lived experience as their subject. Which is more perverse?

So many of the PHOTO 2022 images strewn around the city’s public spaces speak this visual language of socially conscious documentary-like magic realism. The genre seems more proximate to Squarespace stock images for striving millennial creatives than anything I’d consider good art. But clearly other people resonate with this mode of image-making—Babin-Beaudry’s series appears in Melbourne as a Portrait of Humanity global prizewinner. Ultimately, this is a matter of sensibility, but moralising pablum leaves me wanting more.

It’s fitting that Charlotte Rampling’s portrait features prominently in the Jewish Museum exhibition. Often, looking at Newton’s images, I thought of the actress opposite Dirk Bogarde in The Night Porter (1974). The film follows a chance reunion in a Vienna hotel between a former SS guard and a woman with whom he had a sadomasochistic relationship in a concentration camp. I have never been to a Melbourne Cinematheque screening that left an audience so unsettled. The Night Porter is the diametric opposite of PHOTO 2022. It is devoid of liberal humanist message or moral. Instead, the film’s enduring success lies in visceral images and the electrifying dynamic between its two leads. No one who has seen The Night Porter can forget Rampling slinking through a sickly green-lit bar bare-chested in suspenders or placing her hand onto a pile of glass beneath Bogarde’s foot. Eros, ambiguity, violence, and, let’s face it, preternatural beauty make for a pretty good picture. Helmut Newton knew this. Onya, mate.

Cameron Hurst is a contributing editor of MeMO Review