Hans and Nora Heysen: Two Generations of Australian Art

Rex Butler

I was quite prepared to come to Hans and Nora Heysen: Two Generations of Australian Art like a Countess blogger. Yet again the pairing of Nora Heysen with her father Hans, as though her story could only be told through him. Yet again the “Australianising” of Australian art history when this is also a German story and, when Nora goes overseas to study at the Central School in London, an English story.

Why not break with precedent and give Nora her own show (there have been plenty of Hans')? Why not try in some way to de-nationalise the Heysens, to see Hans not as the inheritor of the Heidelberg School and precursor to Albert Namatjira, but as an artist who spent time overseas and at least in the early part of his career essayed a variety of European approaches to the landscape? Why not see Nora as even more shaped by her education and experience overseas and, like so many Australian women artists, fundamentally uninterested in a “national” art?

After having bought one's ticket and before entering the show, it would have been easy to think of Hans and Nora Heysen as the kind of curatorial mis-step the rehanging of The Field proved to be, when the no-brainer complement to the exhibition (not something tucked into a small room some three months after it opened) would have been a survey of Australian women artists of the time not included in the notoriously male-heavy original. It just wasn't the moment to attach a Robert Hunter retrospective—medium-good though he is and as cathedral-like as it looked—but several roomfuls of hard-edged abstract paintings by the likes of Lesley Dumbrell, Margaret Worth and Alison McMaugh.

But it wasn't quite as easy to feel this cockfest-style resentment as one walked through the show and started looking carefully at the works. Although it catches itself out a few times in its didactics—speaking of the way that Nora “wished to avoid more comparison of their work than was inevitable” while doing this itself, or Hans speaking of the way that art was “essentially cosmopolitan” while still casting it as an Australian story—it is at least sensitive to the new ways of thinking and writing about art history. And the artistic evidence itself cut against the claims that Nora's work has been unfairly dealt with in the writing of Australian art. Although she lives and paints for a long time, it would be fair to say that her best work was done while she was still in her twenties. She was prodigiously talented—much more so than her father—but I think her appointment as a war artist in 1943 when she was thirty-two was disastrous for her practice. It led to a looser, sketchy, even sloppy style that had her by the end—and there is no worse insult one can make to any Australian artist—painting like Margaret Olley.

Put simply, the takeaway message of the show is that Nora Heysen starts off better than her father and gets worse and Hans Heysen starts off worse than his daughter and gets better. (Intriguingly enough, there is another great Australian “parental” story, admittedly with sexes reversed, touring Australia at the same time: the Margaret Olley and Ben Quilty retrospectives, currently on at the Queensland Art Gallery and soon to arrive at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. And, frankly, it is a sign of how far the national has devolved as an explanation of the art made here and by Australians that we have to look to these two for a confirmation of who we are.)

But where is the evidence for what we are saying? Hans Heysen arrives in Australia from Hamburg in 1884 as a seven-year old boy. He studied at James Ashton's Art School in Adelaide when sixteen, and his early works—given our later understanding of him—are surprisingly eclectic.

In his Evening in the Hills (1897), we have a Jacob van Ruisdael foreground and a John Constable sky. In his later Meadowsweet Scotland (1904), we have a Barbizon School foreground and a Claude Lorrain background. And even in works like Mystic Morn (1904) and Sunshine and Shadow (1904–5), which we might think of as more distinctively Heysenesque, the same improbably cleft tree appears and the background is like an Art Nouveau theatre screen. (And let us be under no misapprehension: for all of the Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist rhetoric around Heysen, the way he is understood as the great painter of the Australian bush, as though he has some “natural” affinity with it or is even something of a proto-environmentalist—and again the didactics for the show indulge this—his work is absolutely culturally mediated and invariably completed back in the studio.)

In 1899 after some early success Heysen went to Paris to study at the Académie Julien, the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Colarossi, but even here his work fundamentally lacks its own style. Take, for example, his From the Apartment Window, Paris (1901), painted from his fifth-floor studio in Montparnasse, which is absolutely like Camille Pissarro's version of the same street some four years before, or his Adelaide Railway Train Station (1906), painted upon his return, which of course is indebted to Claude Monet's paintings of Gare Saint-Lazare, some forty years earlier.

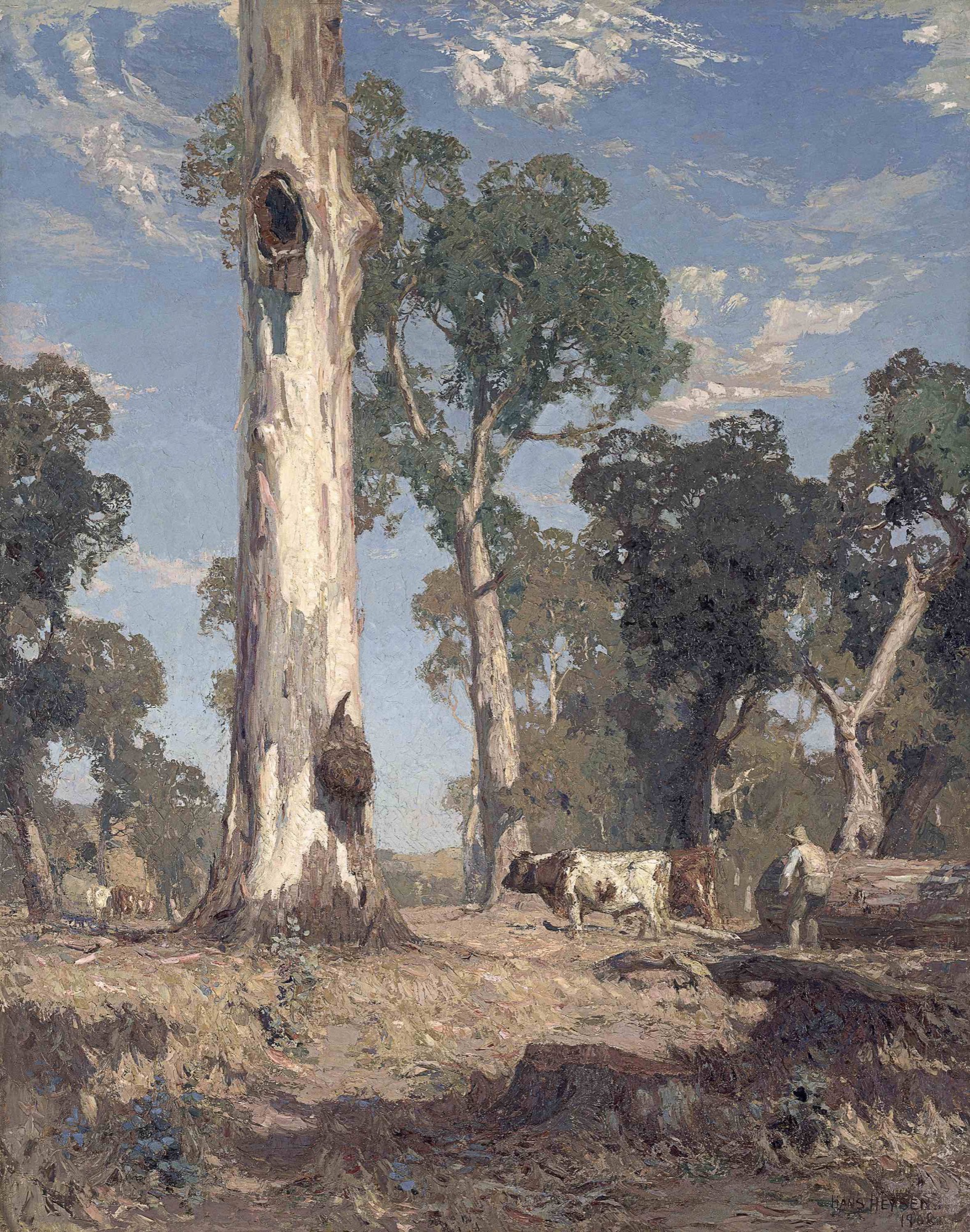

Heysen only hits his straps later—after much appropriation and experimentation—with such works as A Lord of the Bush (1908), although that owed much to the Scottish artist Edward Horn and his use of the palette knife, and Red Gold (1913) and Approaching Storm with Bushfire Haze (1913), although even here we would want to suggest that rather than any real “fidelity” to the Australian bush we have a kind of Poussinesque (or even German) Neo-Classicism. I'm even tempted, following the exhibition Brave New World, held at the NGV in 2017, to think a connection here with a kind of reactionary nationalism that was at the time sweeping the world (and it is not perhaps coincidental that Heysen was a friend of Lionel Lindsay, although he did admittedly break with him over his anti-semitism).

In the last triumphant room of the exhibition—wholly devoted to Hans Heysen alone—we have maybe Heysen's best work, the late career watercolours of the Flinders Ranges. We no longer have the dusty browns and faded blues of the paintings of the teens, but extraordinary shadowed indigos, violets and purples. There is an obvious connection with Namatjira—whom Heysen supported—and coincidentally the Gallery has just acquired a new Namatjira that is just like these late Heysens, installed upstairs on level 3, MacDonnell Ranges at Heaventree Gap (c. 1950s).

For her part, Nora starts off with a bang. How many fifteen-year olds draw like her 1926 pencil Self-Portrait, or nineteen-year olds paint like the brilliant Vermeer-within-Vermeer of Cedars Interior (1930)? And then there is the extraordinary Ruth (1933), a portrait of the local farm worker Ronda Paech, which has got to be one of the best portraits in the history of Australian art. There are the thick bushy eyebrows, the strong pulled-back shoulders, the pure black dress, the thick plaits, the mesmerising off-kilter eyes, the crossed arms, the strong chin, with just the subtlest hint of erotic self-decomposition: the curl of hair running down her cheek, the slightly bent forefinger, the small V at the front of her dress.

Then Nora goes to England with her family, but staying on to study at London's Central School with James Grant, Alfred Turner, John Skeaping and most notably Bernard Meninsky. Meninsky and his co-teacher Mark Gertler were in fact to have a decisive effect on a whole generation of Australian artists—James Cant, Eric Wilson and Jean Bellette—and so it proved with Nora.

Take her Down and Out in London (1937), with its small, stippled, post-Cézannian brush marks, typical of the English style at the time (Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman, Camden Town School) and another image that features an interior feminine space. Then there is the slightly earlier English Breakfast (1935), which features similar, if not loose then at least visible, brush marks so unlike Nora's work back in Australia.

We would want to think, as part of a non-nationalist art history, that Nora's time overseas was the making of her, but instead we might suggest that her formerly seamless painting style—witness the beautifully luminous Eggs (1927) in the show—was somehow fatally compromised by the famously sculptural, disaggregated painting manner of the Central School. The exhibition has a series of revealing comparisons of the same objects painted by both Hans and Nora: a pair of Onions of 1927, Hans' Roses (Souvenir de la Malmaison) of 1930 and Nora's of 1946. Nora's onion before her trip is if anything better than Hans', but her roses painted after are distinctly worse. (Hans had even previously criticised Nora's flower paintings for their lack of overall unity, and this is absolutely the case for her later efforts.)

The final straw perhaps was Nora's time as a war artist in New Guinea. Necessarily painted in the field and hastily, her images are loosely brushed, improvisatory, uncomposed. They did not suit the smoothness, seamlessness and all-overness of her previous style (so different, as we say, from the frequently composite nature of Hans' early paintings). Take, for example, her Theatre Sister Margaret Sullivan (1944) or her Dance in the Sisters' Mess of the same year: they justify themselves, as so much war art, not by any inherent artistic value they might have but by the supposed importance of their subject matter. There is a kind of decorousness to both works, even kitschness, that we find also in such early Hans works as The Water Pump (1899).

And, after the war, Nora paints already like an old woman, loosely, freely, carelessly. Of course, like many women artists of the time—even those with such a pedigree as hers—she was overlooked, written-out, forgotten. But her work appears amateurish, the kind of thing you find in municipal art shows (or Margaret Olley). There is a poignant late photo taken in 2003 of the now truly elderly Nora in front of her father's Red Gold, and it is entirely true what she feared and what this excellently curated show demonstrates despite itself: that she lives on as a reflection of her father.

If we want a triumphalist history of women in Australian art, the show to see is the Art Gallery of Ballarat's Becoming Modern: Australian Women Artists 1920–1950, in which Nora is represented in the catalogue. Hans and Nora Heysen: Two Generations of Australian Art was more complex, nuanced, even troublingly Oedipal. Ultimately, it was a good idea for the NGV to stage an exhibition of Hans and Nora Heysen together: their relationship is more interesting than either of the artists by themselves.

Rex teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.