Gordon Bennett, This World Is Not My Home; Mia Boe, Suspicion Is Proof Enough

Eden Fiske

I’ve seen the shows twice now. The first time, a swarming opening—well deserved in my opinion. The second, on a quiet afternoon alone. The shifting tempos of Mia Boe and Gordon Bennett’s paintings hum against the white backdrop of the gallery walls and against each other as I move between the two small rooms of Sutton Gallery. Later I’ll hum the closing chorus to Albert E. Brumley’s “This World Is Not My Home,” the gospel song that shares its title with Gordon’s show. The song’s haunting sweetness sticks in my head:

Just up in gloryland, we’ll live eternally,

the saints on every hand are shouting victory,

their songs of sweetest praise drift back from heaven’s shore,

and I can’t feel at home in this world anymore.

Much like the song, Mia and Gordon’s paintings traverse territories of longing and belonging. Through their ability to speak to the domestic and existential within the same breath, they share a distinctive quality: transporting the viewer further into their landscapes, where their eye can shift and wander. There is a cool distance and a personal familiarity that emanates from the way each artist represents the land and the vignettes that puncture that range. Each piece drives my vision across its surface. In the two artists’ landscapes I scour for fragments of a whole and instead find something more akin to a mirror or a dream. I come back to this again and again.

Gordon’s work is on show in This World Is Not My Home, an exhibition curated by Tim Riley Walsh in dialogue with the artist’s Estate. It’s a modest survey of familiar and lesser-known works from the 1980s to 2000s (Gordon passed away in 2014). Gordon’s paintings have captivated me since my first encounter with them. My love for his painting voice was first found in the materiality of the work itself. Gordon has a distinctive style, simultaneously balancing corporeal and viscous gestural painting across a sleek and coded intellectual ground. His ability to invert this dynamic masterfully and at will almost feels unfair. Later on in my art history education, my interest in his work expanded and changed. The liminal spaces Gordon painted and wrote about, which I had always felt radiating from the canvas, spoke to something deeply personal in me. His desire, recurrent throughout his oeuvre, was to articulate the complexity of Aboriginality in a post-colonial present. His process of doing so through the current of existentialism, rather than dipping into the same stagnant puddle of identification and classification, bears a gravity that I find difficult to articulate.

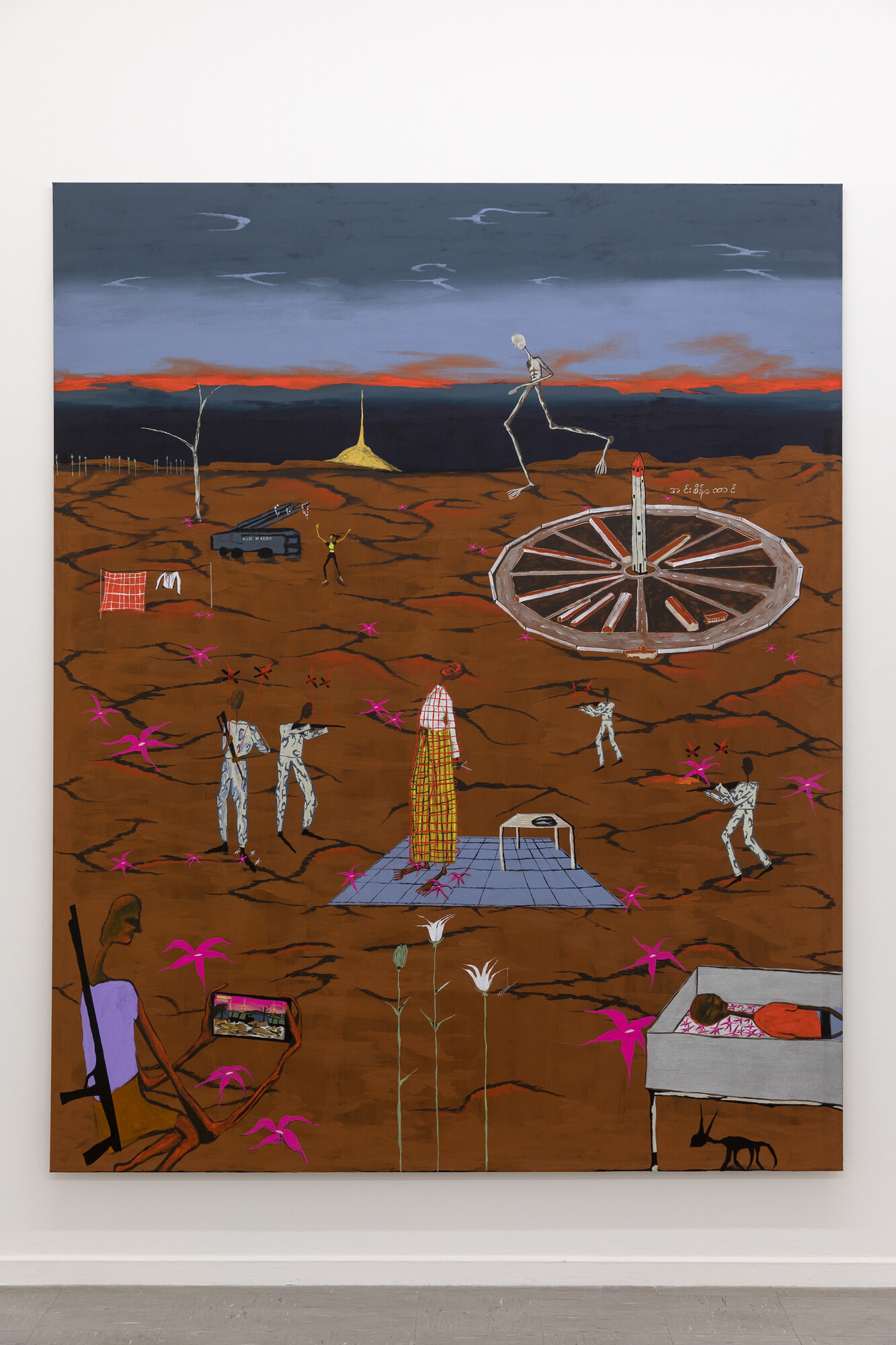

Mia’s exhibition is titled Suspicion Is Proof Enough, and brings together recent paintings responding to current political conditions of Myanmar. In her work, we see a gripping talent exploring the visual tropes of modernism whilst conjuring scenes that reflect a deep understanding of post-colonial art. Her paintings carry a fondness for Gordon’s pictorial architecture, often leaving the viewer to excavate phrases and flashes of chaos from a flat acrylic veil. While Mia’s success as an artist cannot simply be reduced to Gordon’s perceived influence, the two artists do share multitudinous connections. Mia’s work gives credence to a notion that Richard Bell once espoused: that Gordon’s legacy has an intergenerational quality that allows others to build off its foundations. The connections created by the exhibition of these two artists in adjacent spaces at Sutton Gallery is affirmation that we are still very much located in territory searched by Gordon.

The three paintings that make up Suspicion Is Proof Enough are in the first and smaller room of the gallery. Each canvas is of a commanding size, and the trio appear to form an impressively spaced triptych when viewed from the distance of the entrance door. The first and darkest of the three is Interrogation Room (2023), in which we find a scrannel and downcast individual etched against the chiaroscuro of a cell, duct tape over mouth. The hi-vis bars that pour down from the painting’s brim, along with the way the despondent figure huddles in the empty space, conjures up one of Francis Bacon’s seated figures. Yet while Bacon was focused on the psychology and depth of his subject’s interior anguish, the motive of our subject’s imprisonment in Interrogation Room speaks to a more complex, political narrative. What story is Mia telling here? Her narrative unfurls when I consider this individual in relation to the bedlam of a scene in an adjacent painting, Legacy of the Enumerator (2023).

Here, the overt surveillance that curator Tim Riley Walsh outlines in his erudite exhibition text, “The Future of Nostalgia,” is palpable. Under the glare of the foreboding Insein Prison, a Heironymous Bosch-style frenzy is erupting. The turmoil of the scene ensnares the population of the canvas. There are weapons in hands pulled by puppet strings and bodies both bound and in caskets. The horror is only broken by the gentle reprieve of flowers, quickly identified as poppies, which are just as quickly identified as opiates. Mia manipulates and tilts the perspectival space of the earth in the foreground of the painting, which is riddled with geometric cracks and the peaks and troughs of valleys. The bloody glow across the soil is mirrored in the sky. This haunted landscape seems both complicit in and indifferent to the tragedy. It is not the last time we will sense this particular effect in the exhibition. At the centre of the painting, we see an individual grasping a slingshot. The figure is static on their kitchen tiles, appearing bound by a grid. A fish lays lifeless on the tabletop. Noise and confusion bleeds into the domestic quadrant and back out again. A genuflecting figure hovers over a phone screen in front of the open waste. Our sense of geography is toyed with as this place begins to feel more familiar.

Section 505 (2023), Mia’s third painting, pulls us out of the cacophony of Legacy of the Enumerator into something equally eerie and discordant. The overt surveillance and violence of the state shifts arenas. Instead, we see the covert and claustrophobic manifestation of this bondage in a more intimate context. The painting, which takes place in the seemingly innocuous setting of a tea house, has been painted with this sense of closeness. The flat ultramarine blue of the sky fades into a belt of scuffed bitumen, which dwindles above an interior scene. A grainy wooden floor flecked with watchful eyes and the omnipresent leer of state surveillance encloses one of the artist’s trademark figures, who carries on amid the tension. A newspaper laid out flat on the table displays redacted text and the statement “we are watching” in Burmese. Again, the painting’s only figure (whose Nolanesque aesthetic is palpably colonial) seems to be in a state of resignation—a feeling that is bolstered by the artist’s knack for rendering ambiguous facial expressions.

As we also encounter with Gordon’s works, Mia loads the pictorial space with threads that weave in personal reflections as well as thoughtful social commentary. The title of Section 505 derives from the current Burmese military junta’s provision of the same name, which reserves the right to punish vocal dissidents. In Myanmar, tea houses are a meeting ground for members of the community. People gather to share and discuss their lives. Under Section 505, tea houses have become both essential and acutely dangerous spaces. The quiet drama imbued in the painting again speaks of the industrial mentality the state brings to violence, which is enacted upon people and atop the land.

Walking across the threshold and into the second gallery space, where The World Is Not My Home is installed, I’m reminded of Gordon’s versatility and technical range. There are eight canvases and one vitrine holding some works on paper. The show begins at the chronological end and works backwards in the artist’s catalogue. This effective curatorial tool illuminates the artist’s labour and displays the many visual and thematic languages Gordon found to express his ideas. The first canvas I stand in front of is perhaps one of Gordon’s finest works painted under the brush of John Citizen. Citizen was Gordon’s alter ego, a pseudonym that allowed him to push further into his existential project. Interior (Two Chairs) (2008) utilises the colour-block flatness of a suburban Metricon home. These flat sections are interspersed with painterly, arabesque-like washes on the sideboard and on the “Contemporary Aboriginal artworks” that hang as decoration on the wall. The personality carried in the more gestural brushstrokes, reminiscent of the neo-expressionist David Salle, speaks volumes against the reduced and entirely subdued pictorial space. The control Gordon employs here is part of the way he draws the eye in.

Once you’re in the domestic scene, it becomes a theatre for the recurring existential question of belonging. Rather than placing the world in binaries himself, Gordon uses polarity as a mechanism of flux. Gordon’s greatest scholar, Ian McLean, has convincingly argued that,

Gordon does not take the quick route to identity by seeking the centred discourses of nationalism and Aboriginalism, but recognises that identity is an existential project in which “the Other determines me” … the relationship between identity and otherness is not one of a frontal opposition but rather an oblique interdependence. To be “in-the-world” or with others, is “not to be ensnared in it” … but is a type of habitation or haunting.

In works like Interior (Two Chairs) (2008), this habitation takes place in the empty domestic space just as it does in the outside world. For Gordon, as with Mia, the haunting enacted on the landscape does not end at the front door; the domestic overlays the already-bloodsoaked ground.

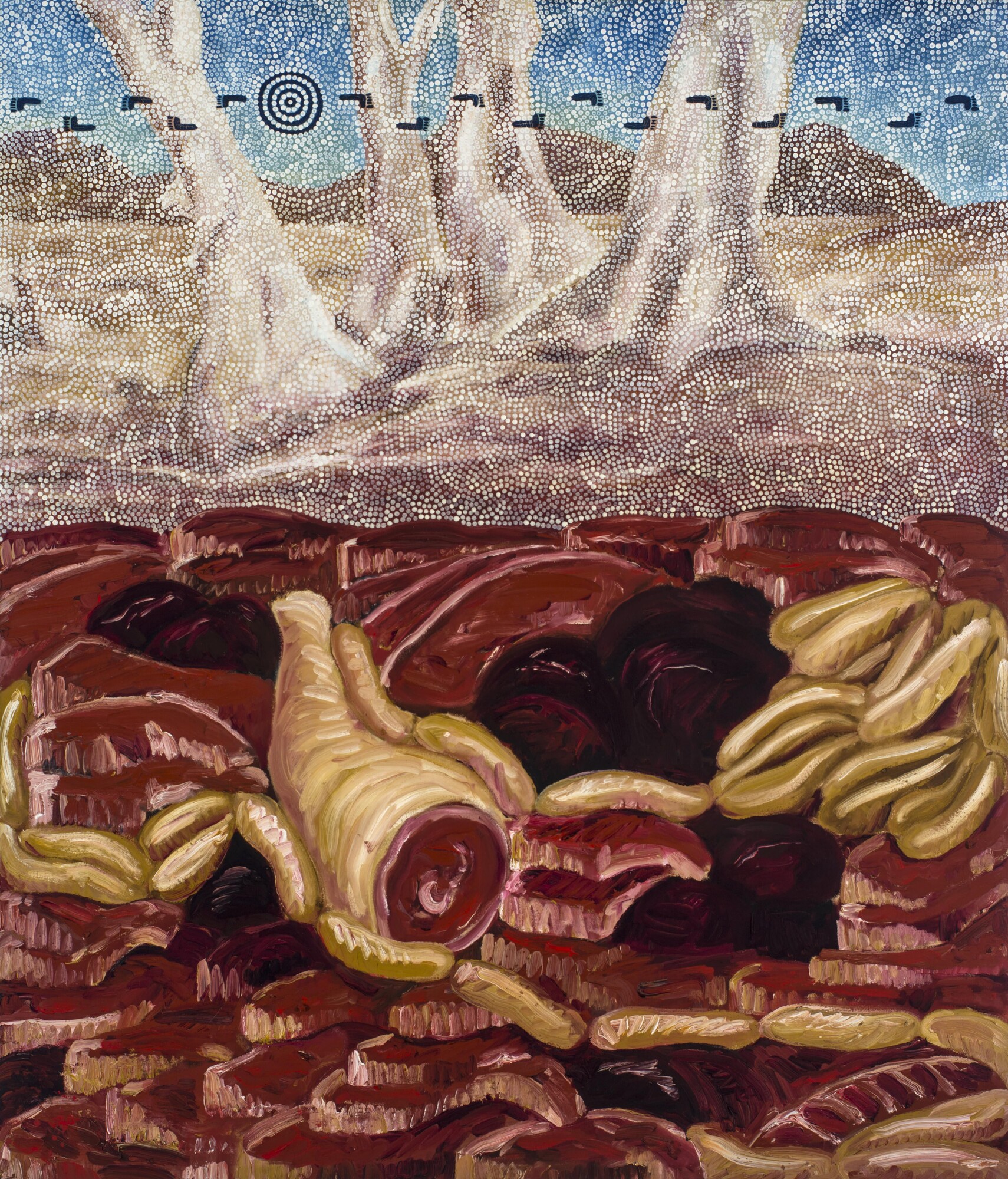

The final canvas of This World Is Not My Home, hung at the only exit and entrance to the exhibition, is Landscape Painting (1988). This work, from Gordon’s time at art school, has a cramped and fleshy quality often found in his early paintings. Thick globules of oil paint whirr in the lower section of the canvas, where Gordon has morphed the landscape into a scene of butchery. Soutine’s beef carcasses come to mind in the impasto gore. Atop this section of the painting, a receding Namatjira-style bushscape is overlaid by a swathe of shimmering dot work, recalling the Central Desert artists of Papunya. Gordon points to discussions about art market commodification and Indigenous art through these acute visual cues. The familiarity and affection that Australia has for these accepted modes of Aboriginal expression is propped up by a violent and writhing undergrowth.

In the closing paragraph of Gordon’s seminal text “The Manifest Toe” he conjures the myth of Narcissus to describe the Australian condition: “Obsessed with its self-image, gazing into the mirror surface of a still pond.” Gordon, aware of the illusory and stagnant reach of this vision—of identification and classification entirely—finds his likeness in the moving surface of a river instead. This river holds all fragments of our alternative histories. Rather than falling in love with his own static reflection, he sees it in a state of flux. Embodied in his understanding of self is an amalgamation of past, present, and future. Some would call this the Everywhen; others would call this The Dreaming. The visual language Gordon found to accomplish this mission was both refined and genuine.

Gordon, like Mia, imbues the land with a haunted quality, an unease that exists in the colonial present. This idea is as true in Gordon’s early paintings as it is in Mia’s now. The two artists interrogate the concept of home, of longing and belonging. I notice this feeling in myself. And in Mia’s work we see not only the echoes of Gordon’s legacy but also the desire to build upon it—to create work that continues to examine our sense of be/longing. It’s a project that continues to send ripples across the surface of the pond.

Eden Fiske is a writer and painter born on Yorta Yorta Country now living on Wurundjeri Country.