Seren Wagstaff, We Who Were Digging, 2024 (detail). Photo: Jessica Maurer.

Garden Variety Dykes

Laura Luciana

Firstdraft is Sydney’s reliably friendly gallery to the emerging and early-career, and has long been a necessary home to first solo shows and experimental, non-commercial group shows. Its location is roughly triangulated by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Art School, and UNSW’s Art and Design campus, which positions it at the service of these student makers and audiences. Firstdraft, apparently, is also equipped to host “pleasure toy” making workshops, which is the accompanying public program for one of the current exhibitions, Garden Variety Dykes.

The exhibition, curated by artist Tay Haggarty, first opened at the end of 2024 in the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens in Haggarty’s home of Meanjin/Brisbane. Now, it has been lightly reconfigured for its showing in Wooloomooloo’s Firstdraft. In contrast to the gallery’s other current exhibitions, Garden Variety Dykes offers a meditative oasis in the hectic cityscape. Haggarty has mustered a classically “dyke”-y drive to organise, and gathered lesbian-aligned artists Abbra Kotlarczyk, Tiana Jeffries, Seren Wagstaff, Amy Sargeant, and Annie Monks to respond to the 1994 anthology text from which the exhibition takes its name.

Garden Variety Dykes, the text, is staunch, sentimental, and a little sexy. The book collects lesbian writing about gardening “in places as divergent as a New York City apartment and the wilds of the Australian bush.” The nexus of rural and urban is a dichotomy that the artists in this exhibition are also probing. And they are literally probing. Even in the thrum of the opening, it’s hard to miss the gently, consistently thrusting machine that faces the gallery’s northern wall.

Installation view of Garden Variety Dykes, 2025. Photo: Jessica Maurer.

It doesn’t stop: at a curious pace the machine thrusts two cast silicone fingers towards a small hole in a makeshift wall that has been erected in the gallery’s window. In the bare plywood a small hole has been cut, big enough to comfortably poke two, maybe three, fingers in, and ease some dirt out from inside the wall’s cavity. The installation by Seren Wagstaff, We Who Were Digging (2025), uses the same erotic metaphors as the 1994 text, where digging represents the sensual contact between the gardener and the earth. Or, in the words of one of Garden Variety Dykes’ authors Emma Joy Crone, “gardening is a healing process, plunging fingers, hands and feet into the mother who sustains.” The machine’s two fingers continue to coax out more dirt from the hole. It reminds me, of course, of lesbian sex, but also of propagating seeds in soil just finger-deep, or being a kid and imagining digging to the other side of the earth—and Wagstaff’s machine can go for hours!

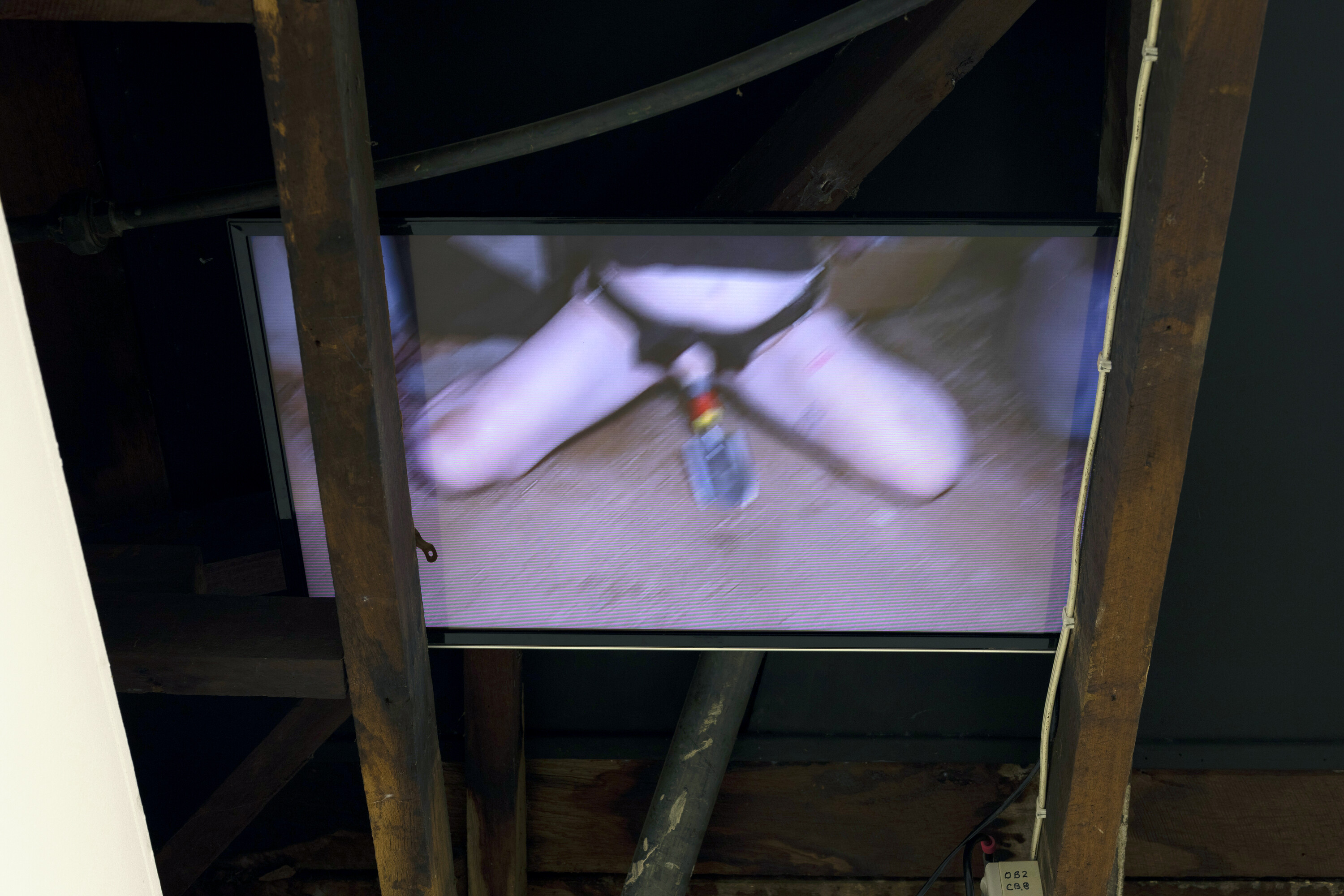

A second component of Wagstaff’s work is easier to overlook. Hidden above, in the structural beams of Firstdraft’s ceiling, is a single screen showing a moving image work made in the underside of the artist’s Queenslander home. Here again Wagstaff doesn’t shy away from showing the tools of gardening, or of lesbianism. Shown kneeling, cropped from knees to waist, she thrusts a trowel in a strap-on harness. It’s a really funny assemblage of objects that would seem threatening if it weren’t so absurd. In slow motion, the artist flicks the dirt from her trowel towards the camera, as if to impress or seduce you, there on the exposed ground under the house.

Seren Wagstaff, We Who Were Digging, 2024 (detail). Photo: Jessica Maurer.

This is the technology of gardening: necessitated by utility and sustained by resourcefulness; it is also done for pleasure and for nourishment. However, the impulse towards ecosexuality isn’t just siloed in the garden, or the domain of lesbians. Increasingly in environmental art, ecosexual practices seem to bear conversations about desire, and absorb posthuman modes of thinking to articulate discourses about the earth and the climate in the contemporary art world writ large. Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens minted the term in a manifesto for mass playful deployment in 2011. Australia-based duo Pony Express toured an Ecosexual Bathhouse nationally and overseas from 2016 to 2022. The 2022 Venice Biennale The Milk of Dreams showed a Zheng Bo video of nude, gay, male dancers and their erotic relationship with the ferns in Sweden, next to an Octavia Butler-inspired, gently orgiastic and anti-speciesist video by Eglé Budvytytè. More recently and locally, Sydney Festival Carriageworks hosted a Justin Talplacido Shoulder work called Anito, confronting colonial histories with an embodied folkloric and earth-amorous narrative through the medium of dance.

Tay Haggarty, BIRDWATCHER, 2024 (detail). Photo: Jessica Maurer.

Garden Variety Dykes’ embrace of ecosexuality isn’t uniform. The impulse towards earth-loving is more speculative in Kotlarczyk’s gentle textual paper works, for example. Seemingly taking cues from David McDiarmid’s Rainbow Aphorisms, the text imagines the sexual agency of some of this continent’s most ancient parts in the form of personal ads for she-oaks and hornfels. Amy Sargeant’s compelling soundscape, a sparse noise and drone-influenced track, scores the room, inviting viewers to stay a little longer to notice these more delicate details of the exhibition. Haggarty’s BIRDWATCHER sculpture sits defiantly in the middle of the exhibition, flirting with the idea of being sat on. As a sculptor, Haggarty is oriented towards a kind of queer abstraction that lends itself to elegant sculptural forms, and in the past they have been engaged to make public art for resting or playing on. BIRDWATCHER resembles modular furniture or fashionable public architecture, reimagined as a comfortable seat for the tranquil practice of birdwatching. The recycled Australian Rosewood folds on its own hinges, sitting in a bed of birdseed. It doesn’t so much resemble your rental’s suburban backyard as it does a botanic garden, a public garden, drawing the politics of our relationships to these public spaces into the remit of the exhibition.

The most tangible way that the show revives nineties-does-seventies lesbian feminism is in the form of the workshop. Annie Monks, an artist and sexologist based in the Northern Rivers, was invited to conduct the accompanying public program for the show, boasting a waitlisted event that was sold out a while before the opening. The workshop, which also took place alongside the exhibition at Mt Coot-tha, draws on an existing practice of Monk’s. She guides participants not only through making or glazing their own “pleasure objects” (which I am told may include but are not exclusive to dildos or butt-plugs), but through the Indigenous practice of inner deep listening through clay. One component of the practice is being led through awareness-increasing exercises to refine the vision for the pleasure toy that you will make. The other kind of ambient and heartfelt part is that you inevitably are sitting around a table with lesbians getting your hands dirty.

Whether related to the unique architecture of the Queenslander home as in Wagstaff’s video, or gesturing to public space as in Haggarty’s sculpture, place is important to the works in Garden Variety Dykes. The exhibition is even a little defiant in saying that the metropolis isn’t the most conducive setting for this lesbian way of life. Actually, the lesbian cultures recorded in the text and the exhibition operate to decentre “metronormativity” (a term the exhibition borrows from Jack Halberstam) in the queer life that they cultivate. None of the artists are from Sydney, nor does the show really require the city to come to fruition; rather, the city needs Garden Variety Dykes. Perhaps it’s worth noting that Firstdraft does not have a garden, not even some turf by a path. Its inner-city front yard is all concrete.

Garden Variety Dykes isn’t about making encoded dyke sexualities visible, but instead reviving the political- and action-focussed era of 90s lesbian organising and making. Just like the 1994 text, Haggarty has assembled an ambitious array of ways to live in our gardens with our sexualities, cultivating their relationship to the earth in a time when this is imperilled by precarious rental contracts and the climate crisis. Gardening is sweaty, sexy work, the earth is erotic, maybe because of the ways that we touch it, maybe because its bounty is so seductive.

There’s a simple reason to re-cultivate a sensitive relationship to nature, and I think that this is these artists’ answer to nihilism. An exercise in sensitivity might draw you into the show’s other sculptural and textural details that beg for a closer, more sensual look. To look to the earth, even in a portion as small as a garden, with the potential for pleasure opens it to the possibility for collaboration, for community-building, for play. Certainly, this was the appeal of Garden Variety Dykes in 1994, and it is also the appeal of Haggarty’s show at Firstdraft, so I guess you could consider that hope to be perennial.

Laura Luciana is an artist and writer on Dharawal and Gadigal land. She is currently undertaking Art Theory Honours at UNSW A&D and thinking about talking, creative labour, and jerking off.