Framed

Philip Brophy

1. Fuck Picasso.

Picasso, who sat idly by during the World War, abusing women while many of his friends suffered and died, is the same man who spent the last two thirds of his life doodling fawns, doves and peace signs for the commodity art machine. Picasso, who mechanically palmed off shop-worn elements from the prop closet of classical Greek pedimental design to the public too numb to notice.

That’s artist George DiCaprio and his son Leonardo (yes) from their introduction to the book Struggle—The Art of Szukalski (2000) on the Polish symbolist artist Stanislav Szukalski. It’s edited by LA alt/underground art/design archivists Glenn Bray and Lena Zwalve. Bray was one of the first of the East Coast comix fanatics who stumbled across the forgotten Szukalski in the early 1970s. The story of his chance encounter and lifelong relation with “Stas” features in the Netflix doco Struggle—The Life & Lost Art of Szukalski (2016). It’s the tip of a humongous iceberg of all the art that officiated Modernist histories and activated Contemporary ideologies cannot see. A partial map has always been readily available, drafted over the last half-century by West Coast comix/graffix artists, to whom the phantasmagoria of the dismissed extremities of European Symbolist art was not corny and kitsch but crazed and confronting. For them, the likes of Szukalski offered an alternative writing of art history that never came to life.

Szukalski’s early-to-mid twentieth-century timeline excluded him from the first formidable reassessment of the dark Symbolists in the amazing exhibition In Morbid Colours: Art and the Idea of Decadence in the Bohemian Lands, 1880 to 1914 at Prague’s Municipal House in 2006. The accompanying, hefty catalogue edited by the curator Otto M. Urban is a deep journey through that huge, submerged iceberg. The “decadence” and “morbidity” of this swell of Eastern European visuality is not metaphorical: those descriptors arise from twentieth-century Modernism blocking the flow of fin de siècle Realism and Symbolism (ideologically opposed movements but both highly illustrative and excessively poetic). Picasso is the crowned victor in this historical struggle to trumpet “newness”. Szukalski and his ilk were vanquished (though they are now potentially in the process of being revived).

You see, there have always been two Picassos. There’s the one that “never got called an arsehole” (though for decades Szukalski dubbed him “Pick Asshole”), who heroically shaped Modern Art, formally and politically. There’s no denying that even amongst his ‘round-the-clock expulsion of artworks, there is some incredible work. Then there’s the other one, who was never viewed as an iconoclastic visionary but as a living cliché of Andalusian horniness, drafting psychosexual jerk-porn and sculpting masturbatory fantasias, all in the name of artistic virility. But it’s that first one that persists, both for his supporters and detractors. A through-line can be drawn through the crania of every artist that to this day is upheld as boldly merging activism with their actioned art-making. Maybe that’s why a Picasso effect lingers still.

2. Fucking Picasso.

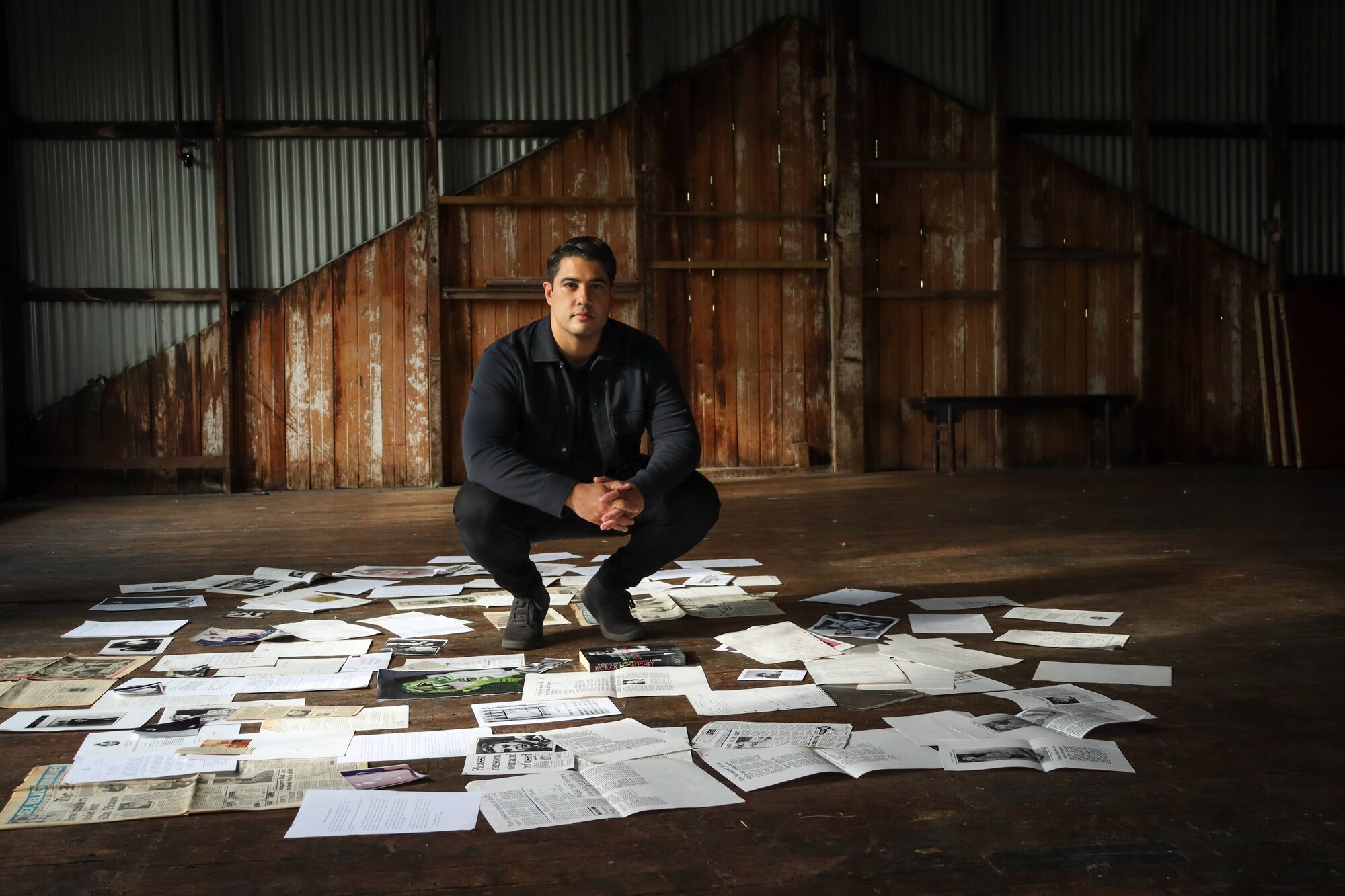

In December 2021, SBS aired the four-part doco Framed (commissioned and produced by SBS, presented by The Feed). It’s about the theft, ransom and return of the National Gallery of Victoria’s then recently acquired Weeping Woman (1937) by one Pablo Picasso. Episode 1 introduces Melbourne’s cultural terrain and the NGV’s position within it, highlighting the purchase of the Picasso as a peak of the city’s assertion of cultural supremacy and the consequent theft of its prized possession. Episode 2 looks at how the police proceeded and the myriad of theories which they and the art world proffered, most of which are ridiculed. Episode 3 tackles the painting’s return, the possibility of the NGV levering its return and local art world conspiracies. Episode 4 concludes with pondering on how the controversy adversely affected innocent parties implicated by the affair.

In truth, Framed is four petite plats of light-hearted, modestly investigative docutainment. So my turgid, forensic review of the series will seem inappropriate, unwarranted and isolated by its concern to treat arts and culture seriously. I doubt anyone who reads MeMO watched the series. But everyone in the arts—including MeMO readers and writers who are at the bottom of the media barrel—are targeted and tagged by these media instances where “art and creativity” (usually the worst examples) are trumpeted in the glorious name of arts advocacy. I would love to ignore Framed, but the show is part of a long-standing cultural dynamic—more a vague odour than a clear mechanism—that affects everyone in the arts. This review chooses to tackle it head-on rather than dance around it.

Framed poses as if it’s generating fresh views on Australian arts and culture history. It doesn’t. Australian media has rarely tackled arts and culture with proportionately warranted seriousness. Why? Because such reports, shows, reviews and panels are not for people who are seriously interested in the arts and culture. And if they say they are while enjoying facile shows like Framed (and the legacy of similarly toned shows on supposedly non-mainstream, pro-culture commissioning channels like SBS and ABC) then they’re demonstrating a shallow perception of art—one that is rewarded by these instances of media coverage that disallow deeper investigation of their subjects.

So this is how Framed presents its case. If you weren’t around in 1986, host Marc Fennell reads out the kind of pre-fabricated research that Year 9 kids do for their Social Studies assignments:

Bob Hawke was the prime minister. Ronald Regan, the US President. Lindy Chamberlain has just got out of prison. And a reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear station has exploded.

The show’s elected cultural commentators on the period do little to push beyond this journalistic compression. Arts writer/editor/publisher Ashley Crawford, journalist/broadcaster Virginia Trioli and artist/activist Gabrielle de Vietri are positioned to qualify the show’s articulation of Melbourne’s cultural identity, despite their careers at some point laying claim to serious arts engagement. They talk about Picasso, Australia, the 1980s, the NGV, and arts funding like parents laughing at themselves looking at their cringey wedding photos. Goaded by the show’s producers, each of them excessively perform for the camera: Crawford does Robert Hughes with upstart cynicism; Trioli does Camille Paglia with lipstick-femo bite; di Vietri credits herself as an “activist”, so there must be some acting at stake. Whatever the case, it is naive to assume that anyone in Australia being interviewed for any media reportage on arts and culture is not strategically playing the game for their own interests. Even if we are being given a distorted view on how these commentators present themselves, then so be it: they lost this particular round of self-promotion.

3. Fuck the 80s.

In 2013, I opened the NGV exhibition Mix Tape 1980s – Appropriation, Subculture, Critical Style. I did so in support of then-NGV curator Max Delany, who already knew my cursive views on the era’s inflated self-importance. But just before the opening, I received the invite and its “jovial” reference to padded shoulders, asymmetrical gelled hair-dos and other rich embarrassments. The prospect of contributing to this smarmy belittling of 1980s bad taste was irritating, but the thought of publicly playing along with this 1990s-style “decade dumping” would have made me look like I was a two-bit comedian from some awful Working Dog production on the ABC. My point is that when the arts in Australia intersects with media or marketing there is always a neurotic “boganing down” or “bloking up” of the art and artists to save the media “creatives” from appearing like pretentious wankers. I pointed out I knew no-one who dressed in the way the invite claimed was the fashion of the time—save for comedians sending up imagined stereotypes of the era—and made sure to name the NGV marketing department as the saps and hacks anonymously hiding behind the invite’s text. This was 2013, but it felt like 1993, reading pithy jibes from the poison pens of stand-up comedians desperately trying to be hip and flip at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival—source of the cabal of personalities who would move on to front just about every cultural show on SBS and ABC for the forthcoming decades.

Framed gleefully paints the 1980s as a bad-taste era (as if the 1990s, the 2002s, and the 2010s weren’t) and keeps returning to that decade’s licensed footage library to “frame” the events of the Picasso theft. 3/4” U-Matic video news imagery is continually interpolated while an interviewee speaks. It creates a numbing overload of empty tokens that prove Melbourne to be a cultural wasteland. The sad fate being readied for Framed is that it already looks and sounds pathetically date-stamped: slo-mo intercuts of “the city”; orange-turquoise digital grading; planar creep tracks over, well, any time a camera is turned on; really bad acting (Letraset-level representations of painters, academics, police, security guards, reporters, the public); desperately stylish dressing of sets and choice of locations for the interviewees. I could be watching the Aussie version of the globally franchised The Batchelor. The deafening lack of any visual flair typical of the Australian film and television industry is proudly present in every frame of Framed. I can hear the breathless thrill its “content creators” feel in their production being of artistic quality.

The 1980s footage is cynically used to contrast with the production’s stylistic mechanics, as if it’s spraying a McDonald’s Thickshake over the walls of the NGV members’ lounge. Patrick McCaughey looks expectedly ridiculous, though it should have been clear to anyone at the time that the only way intelligent views could be rendered media-friendly was through self-caricature. Regardless, we see him continually performing for the news cameras, wearing bowties like he’s a drag performer sponsored by Fletcher Jones doing John Houseman and Truman Capote while dressed in a Chippendale’s gumshoe trench coat. Marc Fennell probably thinks he presents way cooler, with his metrosexual vibe, a harmony of upscale mall attire that speaks denim-rootsiness like a clean-cut fiancé. Picasso went around bare chested with white calico shorts, cos he’s always painting by the sea. Fennell sits and pivots with sleeves slightly rolled up, cos he’s tirelessly investigating, reporting, commenting. This flippant binary framework is tiresome. Yet again, media “creatives” pose their hipness against the worst 1980s-era clichés of nerds, geeks, dags, drongos and bogans. It was insightful in John Hughes teen movies of the era. It is desperately insecure now.

What was my 1986? I had just returned from overseas: the fiasco struck me as a multi-tiered cake of creme de nothing. Purchasing a Picasso in 1986? Bothering to steal a Picasso? Referring to oneself as a “cultural terrorist”? Discussing the ethics of the situation? At that stage I was co-presenting with Bruce Milne the EEEK! weekly radio show on trash culture for 3RRR and writing a monthly column on exploitation videos for Video Age. For me, 1986 was seeing Day Of The Dead, Broken Mirrors, Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, At Close Range, Henry – Portrait Of A Serial Killer and Pretty In Pink, and listening to PIL’s Album, Big Black’s Atomizer, Janet Jackson’s Control, Prince’s Parade, The Cramps’ A Date With Elvis and Sigue Sigue Sputnik’s Flaunt It!. My memory of any art at the time was a melted pool of Transavanguardia, Neue Wilde, Neo-Expressionism and Mambo Graphics (I couldn’t tell the difference between them).

Watching Framed brought this back into my consciousness not because I was triggered by the series but because I lived in a world oblivious and indifferent to the scenarios painted by the series’ episodes. I have no memory of the alleged thieves being called the Australian Cultural Terrorists (or I have suppressed it). But I do remember that in the early 1980s, there were poets and writers in Melbourne pretentiously making connections with or allusions to the Red Army Faction in Germany and the Red Brigades in Italy. The notion of “cultural terrorism” in Melbourne then only existed as half-digested swill coughed up from watching Fassbinder movies and reading Mishima novels. Framed presents most of the ACT’s missives and demands in full. They are the most cringeworthy thing about the whole series. The show’s cultural commentators salaciously read them aloud, relishing in what they variously describe as “delicious”, “witty”, “fantastic”. Their smarminess perfectly synchronizes with Fennell’s YouTube demeanour, perfected in the bitchy news dissection of The Feed. Collectively, they seem blind to the impoverished purple prose of the letters, which to my ear sound like the anonymous, bankrupt missives from millennium blogs like The Art Life.

4. Fuck me—I’m Picasso.

Framed—either in isolation or accordance with gossipy art world assumptions—links the ACT with artists at Roar Studios in Fitzroy. I was so disconnected from the NGV “heist” at the time that I was completely unaware that the Roar artists were momentarily suspects in the police investigation. Framed informs me of this by delivering more irksome revisionism: lionising the plaid-shirt, VB-swigging revolutionaries of Brunswick Street. But as I insist in this review, Framed is not alone in mindlessly rationalising a forced, dominant narrative of rebelliousness and independence in Australia art:

1982. What a mega year it was for the arts (not to mention shoulder pads). Michael Jackson (who back then still resembled a member of the human species) released his album Thriller. The Queen opened the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. And Thomas Keneally became the first Australian to win the Booker Prize, with Schindler’s Ark. It was also the year a group of young, eager and rebellious artists opened one of Melbourne’s earliest artist-run-galleries—Roar Studios, in a former shoe factory on Brunswick Street, Fitzroy.

That’s some journalist for The Age writing about a thirty-year reunion of the Roar artists in 2011. The reader will note the same sociological flash-card sentences posing as history; the references to shoulder pads, just like the “creatives” at NGV marketing; and vilifying Michael Jackson—mocking “Wacko Jacko” at the time being a base level anti-Pop tactic of edgy, stand-up comedians. Framed benefits from a sizable bounty of video and photos documenting the Roar studios, suggesting that the media was not adverse to hyping them. Seeing their canvases, murals and posters flash by in Framed unpleasantly reminds me that their collective output from the early to mid 1980s resembles indie band LP cover art: brushy, overworked, cartoonish, expressionistic figuration, passing as angsty CoBrA-styled sentiments of urgent, street-level urbanity. The hilarious thing is that while much of the Roar artists’ visuality imagined it was channelling East Village logoistic primitivism (a hip marker in art schools at the time) it mostly looked like bad Picasso copies picked up at op-shops and hung in Brunswick Street first wave “retro” cafés.

It sounds like I’m attacking the artists. I’m not. I’m dumping on the way that lazy mediarization of romanticised charades of creativity—especially in Melbourne, the great citadel of culture—are held up by writers and producers who spend careful strategic energy assuring their audience they are not pretentious intellectuals. The Roar artists were media-friendly in that their work wholly confirmed the most basic behavioural assumptions as what motivated artists. Yet the Roar artists ended up suffering the fate of any Young Turk forced through the graduating colon of institutions like the Victorian College of the Arts. Media coverage brightly illuminates their stage, then flickers as they exit to the drab existence of surviving on one’s talent, craft and connections. Those heated divisions of the day cool, leaving documents like Framed to fan dead flames.

Yet the suspicion cast on the Roar artists I think was contextually founded. The badly-scripted, pseudo-revolutionary prose of the ransom letters was typical of that worst indicator of radicalism: a first year tertiary student’s sudden exposure to injustice in the world. Sure, kids get a righteous buzz from realizing the “hidden” systemic operations of repressive socio-political institutions. But deeper or lateral awareness rarely develops from that buzz, as it is flattened by forever returning to that youthful, epiphanic moment whenever one attempts to analyse and critique anything else. How else can one explain the laboured and ignorant repetition of badly acted tropes of revolutionary zeal in artistic production for decades upon decades to this day? How else can one qualify the eternal return to delusional claims to “change the world through art” that progressive and alternative media channels promote and support? The rhetorical demands of the ACT ransom sounds like they could have been drafted at multiple historical points in Australian cultural activism, be it by either Ivan Durrant, Mike Parr, Marcus Westbury, Juan Davila or Mark Davis:

(i) The minister must announce a commitment to increase the funding of the arts by 10% over the next 3 years; and (ii) the Minister must announce a new annual prize for painting open to artists under 30 years of age.

Careful what you wish for: Melbourne got all that and more. While radicals have repeatedly lambasted federal and state support of stultifying opera companies and stuffy symphony orchestras, they seem to neglect the parasitic ecosystem of alternative/independent/progressive arts professionalism that has grown since 1986. It’s a fetid substructure, fertilised by a slow ooze that pumps Melbourne up like a giant inflatable public sculpture, posing as an airy yet obese avatar of this great city of the arts. Our artistic climate is choked by ongoing increases in funding contracts, development incentivisation, corporate sponsorship, media partnering, marketing assistance, cultural stamping, political alignment, institutional branding, and an all-round awarding of prizes for peer-assessed excellence. Framed covers the implied radicalism of the ACT’s tactics as if there is no present context for framing what has happened since.

Dumbest irony: Gabrielle de Vietri—interviewed for the series next to Jules Lefebvre’s Chloe (1985) in Young & Jacksons (how droll, darlings)—delivered near identical agitprop missives three decades later to the NGV via the Artists’ Committee protesting the gallery’s interim hire of Wilson Security during Triennial 2017. The firm was the widely criticised provider of security services for the Manus Island and Nauru offshore detention centres for asylum seekers. The “vents” staged at the NGV by the Artist’s Committee included a symbolic covering up of Weeping Woman with a black cloth bearing the Wilson logo. And the dumberest irony: the bulk of the artworks in Triennial 2017 were obsequious, grandstanding, politically-universalising testaments to the power of artists standing up against injustices in the world. Guernica on the Yarra.

5. Fuck. The Police.

The only dependable voices in Framed are former detective sergeant Bob Quigley from the Victorian Police Crime Squad, former forensics analyst Neil Holland from the Victoria Police State Forensics Crime Laboratory and former NGV conservator Tom Dixon. They remain detached, knowledgeable and unswayed; they are not concerned with performing their selfhood. Their interest then and their reflections now focus on the object at hand: the original oil painting, not what it represented then or now. (At one point, Quigley is asked to read a contemporaneous report for the Herald Sun by Ashley and Jason Romney, which he politely dismisses: “Well, that’s written by a journalist.”) Their voices give a glimmer of what Framed might have been had it done likewise. Instead, we are served a mash-up of a tired Agatha Christie whodunnit and vacuous arts writing typical of The Age. Both Quigley and Dixon express frustration and vulnerability as well as a healthy dismissal of the ACT’s puerile stance, limned with a distaste for the irresponsibility of their actions. Artists like Martin Munz and Gary Willis are also interviewed. They grabbed the gig for what it was worth, but they would have been better advised to reject the invitation—or decline to be interviewed, as did McCaughey, Juan Davila and Anna Schwartz.

The final episode in the series then does a voguish flip. After refusing to use hindsight to posit views of Australia’s still-unformed cultural identity, and effectively making fun of the whole affair, Fennell then looks at an artist couple—Margaret Casey and Peter Rosson—who were accused of the painting’s theft and its return to a Flinders Street Station locker. Rosson it appears was hounded by the police; it caused him grief and aggravation, leading to his break-up with Casey and his eventual suicide. I had never heard of these artists, who enjoyed a large art studio space upstairs above Mietta’s, a landmark Melbourne restaurant that I never went to nor was ever interested in. Casey is interviewed, and she remains angered by Rosson’s subsequent ostracization from the “art world”. The plot then thickens with allegations of their treatment being payback for her reporting being sexually harassed by Rodick Carmichael as a student in 1985. Carmichael was the head of the painting department at Deakin University and art critic for the Herald Sun.

There’s certainly a sad and tragic aspect to these incidents. But Framed is inept at doing anything beyond play-acting humanist responsiveness and collecting empathy points by shifting emotional gear in its narrative (cue the lumpen cut to soft piano chords). A few peripheral interviewees imply that Rosson was robbed of his fame as an artist. But irrespective of his paintings looking like Archibald/Wynne/Moran/Sulman Prize entries (skilled, competent, resolved, expressive) the point editorially avoided by the series is that hundreds of artists are robbed every year of the fame they “deserve”. In fact, the unending support for the unbridled creativity of successive waves of arts graduates may be the key culprit in shattering naive art dreams of Angry Brunswickians who think they are due recognition while they are under thirty.

6. Fuck the media.

It is Framed’s final shift that tellingly exposes the series’ alignment with so much current media production, broadcast and channelling, irrespective of genre, form or format. Every presenter, interviewer, commentator or investigator of any media platform today is at pains to showcase their empathy skills. Yet they simultaneously remain insensitive to things to which they are blind—while accusing others of being blind to what they’re empathizing with in their reportage or commentary. In showing the long forgotten hiccups and flare-ups of those who thought that the Picasso ransom was a vital and urgent affair, Framed had the chance to assess its findings and conclude that the choreographed interplay between conservative, uninformed Melbournians (who could care less about Picasso being at the NGV or not) and sparky, local painters (who dreamed of their work one day replacing Picasso at the NGV) was but a moral mirage of fluffed-up cultural politics and self-centred delusions. It chose to not do so, and instead strikes a conservative journalistic stance: ideologically leaning into the ACT’s aims; championing the Roar artists; back-slapping the archive of journalistic reportage; morally condemning the micro-political negativity of the “art world”; and generally upholding oppressive and limiting myths of “the struggling independent artist”.

Unsurprisingly, no-one even mentions that Weeping Woman is a portrait of the incredible Surrealist photographer/collagist/painter Dora Marr, here performing world-weary anguish for Pablo. He did a suite of four paintings, each a somewhat cursory confection of candied Cubism with heavy black outlines, none of which attain the quality of the larger Portrait of Dora Maar (1937). The most interesting details about the Weeping Woman series is that it portrays the symbolic viewer of Picasso’s famous Guernica—meaning that the work is itself a mediatized version of how an incident is mediatized. Picasso sees newspaper photos of the Nazi bombing of northern Spain; he paints a “Historical Painting” replicating the atrocity’s reportage; then he paints someone figuratively weeping at his own painting.

In Framed, the only person who references Guernica or acknowledges Picasso’s legacy is former detective sergeant Bob Quigley. Everyone else seems embarrassed to talk about Picasso, let alone position what a colonial outpost like Melbourne was meant to gain from importing Cubist portraiture into its state gallery. Maybe this weird repression of Picasso is what created the Picasso effect that is embedded in much politicised contemporary art. When Virginia Trioli interviewed Ai Weiwei onstage at the NGV in 2015 (with more seriousness about art than she parlays in Framed), it played out like the NGV was finally able to grandstand its support for a politicised artist boldly standing up for artistic freedom via Guernica-aligned statements, exonerating itself for attempting to do so simply by purchasing an overpriced artefact back in 1986.

An execrable attempt at passive-aggressive boomer-takedown in Framed is when Fennell disingenuously confides to Crawford “I have a confession to make: I was born in the mid-80s. What did I miss?” It’s a throw-away comment that reveals the moronic uptake of anthropological instrumentality in current TV documentary film-making: the idea that “being there” justifies every view espoused, purely on emotive, subjective or affect laden terms. Watching the world constructed by Framed, I can thankfully say that I wasn’t there.

Philip Brophy writes on art among other things.