Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser, Forced into Images

Lisa Radford

VF No need lookin’?

DD Nothing surprises most of us indigenous women any more. It’s got that way if a flying-saucer was in our midst, we wouldn’t give it a second look.

— Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser, ‘Not quite right, but interestingly queer’, Photofile 61, 2000

I come across the video installation just as finishing touches were being applied and a decision was being made about whether the black-text-on-white-background was a better fit than the white-text-on-black. It is the first few days of lockdown 2.0. Dusk in the backstreets of Collingwood, and I am trying to acquire access to a horizon line before hooking into yet another Zoom meeting where I refuse to be seated. I am thanking the JB HI-FI God for the wireless earpods that allow me to be physically untethered, albeit always connected to a device. We are mobile montaged images in and of real time.

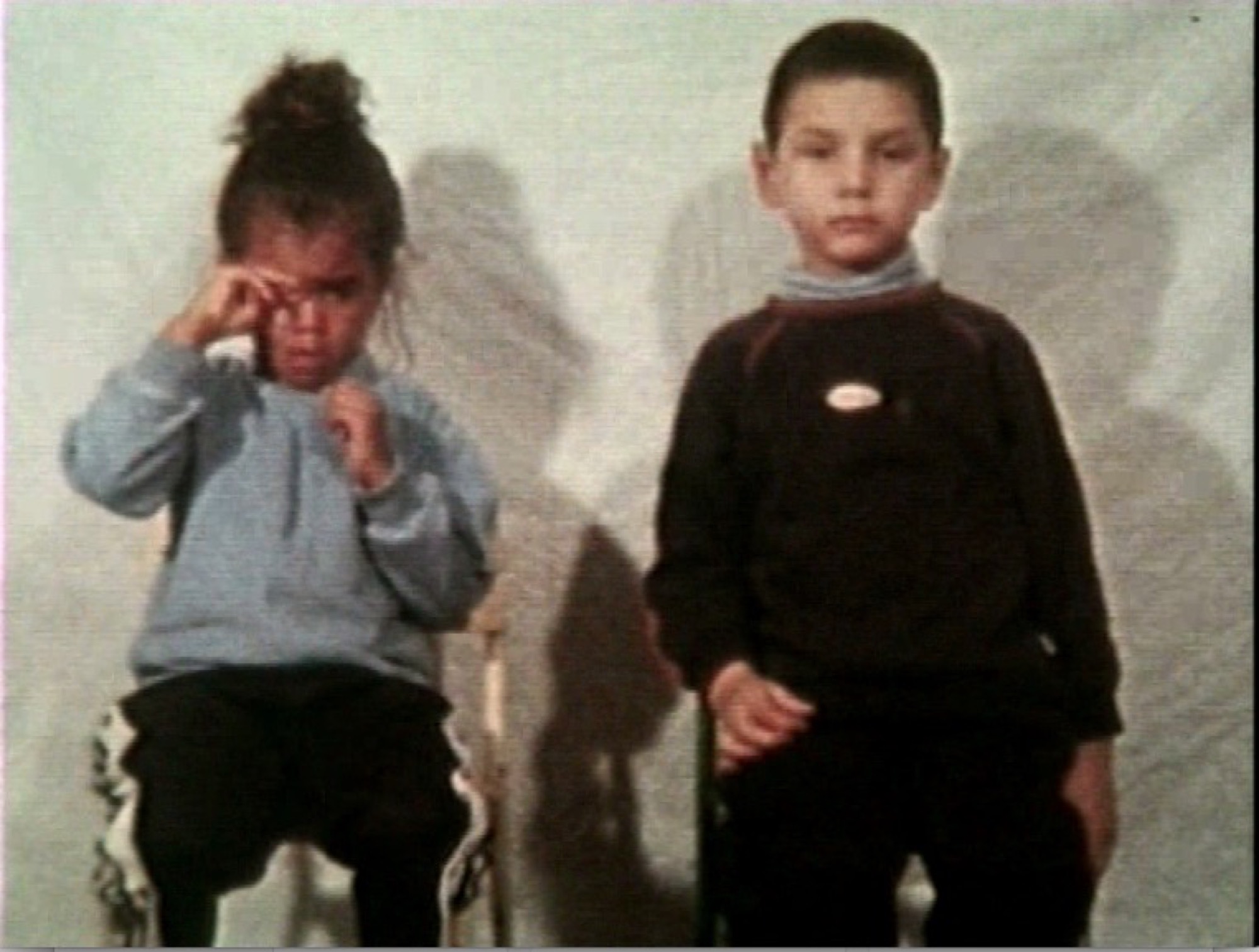

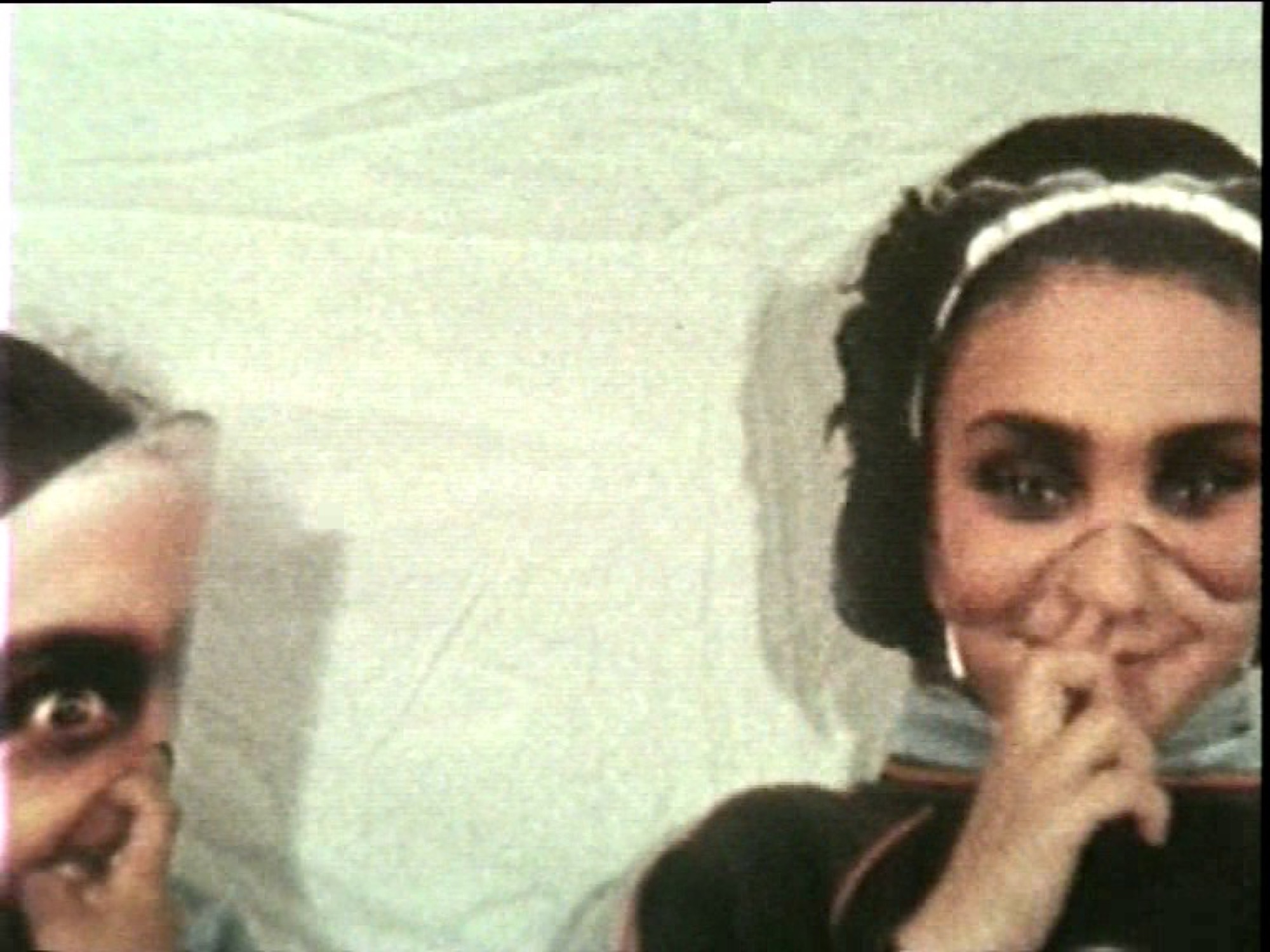

Forced into Images (2001) is a nine-minute-or-so Super 8 film transposed to digital video by Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser. It consists of a series of images or fragments of film of (I later learn) Deacon’s nephew and niece sitting with each other in and out of gestures, performing to and with a camera. The title is as literal as it is poetic. Forced into Images is extracted from an unpublished letter about racial and social stereotypes—“I see our brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers, captured and forced into images, doing hard time for all of us”. The letter was published in the catalogue of a 1982 exhibition, Ethnic Notions: Black Images in the White Mind, held at Berkeley Art Center, California, named after the Marlon Riggs documentary which traces the history of racial stereotypes in America since the 1820’s. Destiny Deacon is well known for her use of Aboriginal kitsch as a device that creates and questions the reality of the absurd theatre of representation we inhabit—forcing us into images.

My access to the documentary Ethnic Notions is via edited fragments scattered on the net. Both the film and exhibition examine images that have decorated the homes of mainstream American life in which enduring stereotypes of African Americans are maintained. The documentary traces the production and consumption of these images as they move from cartoon to public policy, sub-culture to national consciousness. These images have moulded race relations in America for more than 100 years. ‘Forced into images’, as a short sentence, immediately brings to mind how representations of gender, race, age, place and planet continue to impact the way in which we engage with knowledge and news, with what we can come to believe about ourselves and others. Australia, as a colonial and ethnographic test-site rendering its first inhabitants as object to a subject, is a producer of similar stereotypical cultural images. Forced into Images emerges as a phantom phrase, recalling the actions of social scientists—measuring, documenting, counting.

Questioning the creation of such taxonomies, Lila Abu-Lughod argues in her essay ‘Writing against Culture’ that “culture remains too laden with the assumptions of a divide between the knowledgeable scholar (‘subject’ the ‘self’) and the person whose culture is under investigation (‘object’ the ‘other’)”. While specifically referring to the discipline of anthropology and its perpetuation—and lack of recognition—of embedded hierarchies, the oscillation between self and other and the relation to power dynamics is still relevant here. Abu-Lughod explores, in her words, how feminists’ and halfies’ anthropological practices unsettle the boundary between self and other. She shows how they enable us to reflect on the conventional nature and political effects of this distinction, and ultimately to reconsider the value of the concept of culture on which it depends.

A video on-loop dissolves and accentuates boundaries—its title re-iterated and its gestures analysed and echoed. As it is with photographs over time, each viewing is also a re-viewing, a re-seeing moderated by the technical distance of the mechanical apparatus that captures and presents—contexts are cropped, captions contain, repetition reinforces. The language of the image is composed of its materiality and its mode. Projected cinematically onto the large red brick wall that borders the north end of the Peel Street Park, the grainy quality of Deacon and Fraser’s film dissolves into the texture of the bricks of this socially spaced screen. This screening is not framed by a gallery or COVID’s online theatre. Billboard in scale, its presentation is instead closer to cinéma domestique—Fraser notes in an email that this is a portrait not a documentary.

I vividly remember an architect friend pitching a contemporary art version of the Bolshevik agit-train—printing press, movie theatre and complaint office on board, distributing the values and programs of a revolutionary form. In Soviet Russia, this state-based propaganda was delivered to an isolated peasantry. Here in Peel Street I am curious as to the audience—new medium density apartment homes with large uncurtained windows revealing large flat-screen TVs. No longer a signifier of wealth, the televisions are banal black mirrors or ready-to-watch windows. Unperturbed by the projected moving images before me, a couple with their rescued greyhound walk by the tinnies resting on the bespoke social furniture of the park. It is 9.30 pm. This is a different abyss to that examined by Tony Birch in his essay ‘These Children have been Born in an Abyss’. Centring around the hard-to-imagine now early twentieth-century slum of Fitzroy and Collingwood, Birch’s essay examines the myth of photographic truth where the burgeoning technology of photography came to the assistance of the literary slum genre, risqué journalism and the discipline of social science. Both Abu-Lughod and Birch ask what authority documentary images uphold. In stark contrast, Deacon and Fraser’s portrait gives time to time spent and the absurdity of decontextualised gestures, intimacy and image making.

I return to the screen while the young boy, who I imagine to be now in his mid 20s, sneezes. His gesture is copied by his younger female friend, sidekick, sister or cuz—her mimic familiar as form in competitive familial relations. Learnt behaviour, and what do we learn? This film is silent, but its scale seems to sound like “home”. Pitted side-by-side our protagonists look beyond us, to those behind the camera. Responding to cues or simply each other—the performance of a screen test, or perhaps just a test of time.

Birch, acknowledging Jennifer Green-Lewis’s text Framing the Victorians, argues that photography has been able to “provide (the) confirmation” of the truth that realism desires. He claims that while the subject within the frame may be “imprisoned”, it is both the photograph and its “author” who “diminish the significance of human agency”. It is in this way that the slum photography of Fitzroy, acting as documentary record, distributed images repetitively both negative and despairing, reinforcing tropes over which subjects had no right-of-reply.

The domesticity, cheekiness and sleight-of-hand humour of Forced into Images subverts this. Deacon and Fraser’s subjects are always waiting. The post-production editing—sped up, slowed down—segments banal horror, silently slurping icy poles. These carefully montaged images do not measure content as perhaps Eadweard Muybridge’s mechanical sequences might. The no-narrative turn sees the kids choosing masks, one for each, local-printshop and home-styled—the innocent become curious disproportionate forms—adult babies, accidental aliens, squashed in time. I remember Barbara Christian in Ethnic Notions reflecting that the way we are imaged influences how we image ourselves.

In 1927, when art and cultural questions could be found on the front page of a newspaper, Siegfried Kracauer observed that a photograph is a physical “representation of time”. Boris Groys suggests Kracauer’s observations can also be applied to video:

We are contained in nothing and photography assembles fragments around a nothing. When Grandmother stood in front of the lens she was present for one second in the spatial continuum that presented itself to the lens. But it was this aspect and not the grandmother that was eternalised … it is not the person who appears in his or her photograph, but the sum of what can be deduced from him or her. It annihilates the person by portraying him or her, and were person and portrayal to converge, the person would cease to exist.

As Groys points out, for Kracauer every photograph is merely a general inventory of diverse fragments or details. Revealing meaning cannot be photographed because it is invisible and needs interpretation to be made manifest—photography is merely a garbage can, a phantom, a sign of death. Instead of vanquishing death, photography kills, for it captures only the body, the corpse, and negates the soul.

In some sense, this description applies to Deacon and Virginia’s film. Confronted by the gestures of the children and the seemingly domestic and intimate approach to filming, we as viewers determine our comfort and relation to a figural void — the who, what, when, where and why of what we are viewing, the simultaneous presence and recognition of horror, love and the banal. This void is political, rendered and represented in our experience, time and again, by colonial cultural contexts. Google Images, perhaps the most recent form of the colonial archival impulse, was launched in July 2001 (the same year as Forced into Images) allowing for en masse imaging, a contract trace for all-and-sundry. But as with all offices of official collection, something is always missing, hidden from view. Deacon and Fraser’s work, with experience and knowledge of the potential violence perpetuated by image data-collection, playfully navigates the edges of intimacy and imagining. It is mostly an intimacy we are not privy to, and an imaging we must interpret, a slippery relational Warburgian phantasmic science of Kracauer’s mechanical memory.

In the interview ‘Not quite right, but interestingly queer’, Fraser reminds Deacon that she “suggested I ask you about being an artist who’s contemporary, indigenous and lesbian”. Deacon’s reply reveals the space of this slip, “You forgot left-handed. I find that more discriminatory. I couldn’t use a pair of scissors until I was about twelve years old. Plus it took me that long to find a friend who didn’t limp.”

The experience that frames our viewing influences the visibility of flying-saucers and the performativity of our selves.

Lisa Radford is an artist.