Samraing Chea: Universal Drawings

Giles Fielke

Universal Drawings is an appropriate title for the exhibition of 41 works by the artist Samraing Chea currently on show at Olivia Radonich’s new city central gallery, Reading Room. A thoroughgoing millenial subject — Chea was born in 1995 — the suite of 26 drawings in full colour on display in Room 1 is a brilliant homage to the personalised screen cultures that have come to define the first decades of the 21st century. As revealed to me by the artist Rob McHaffie, who proposed the show to Radonich with fellow painter Matlok Griffiths, Universal Drawings is perhaps best understood as Chea’s own riff on Universal Pictures, the century-old Hollywood film studio that has significantly shaped our sense of what the cinema has effected on our perceptions of the world. Chea’s particular pairing of his visionary images with carefully composed one-liners, precisely transform his iterated drawings into emblematic images, also serving as the works’ poetic titles. There is a tenderness and earnestness to the works that is rare in contemporary practice, which often steels itself against the competitive machinations of the market. Here Chea’s intensity, the striking use of colour and the singularity of his obsessions over images are on proud display. It is this vision that McHaffie and Griffiths were keen to promote as a show dedicated to Chea’s work as such.

However, the series of 14 monochrome drawings in heavy lead pencil, on show in Room 2 — each of which were completed in a single day at home — along with the largest single work of the show, Evolution of Urban Planning and New Developments in the USA (2012), demonstrate a deeper aspect of the artist’s process than just screen grabbed quotations of picturesque details. The greyscale series, made throughout 2017, remains untitled and yet clearly presents the horror year that was in an idiosyncratic yet profound melange of disturbingly familiar compositions. In one work, dated March 29th 2017, a mass protest takes place, with the words ‘EXPRESSION SURVEILLANCE’ clearly legible on the side of a vehicle in a militarised streetscape somewhere in North America. In fact, on this date a cycle of all-too-typical geo-political events can easily be found collected online: a car bomb attack in Baghdad killed 15 people, the UK announced its formal declaration of intent to withdraw from the European Union, and the US judiciary scrambled to restrain President Trump’s notorious, on-the-fly immigration ban announced via Twitter, leading to widespread civil protest. Staying out of sight, Bob Dylan agreed to accept the Nobel Prize in Literature on this day at a private location in Stockholm.

Arriving at the gallery, positioned in one corner of the 6th floor of the Nicholas Building, is an aesthetic experience all of its own. Reading Room is a simply laid out and prepared suite of three rooms adjacent to the Caves ARI, with Radonich’s office framed as the Library, which currently features an ‘Arrangement’ by the Sydney-based artist Leahlani Johnson. From the building’s magnificent industrial windows you can see straight down into the pit where City Square used to be, the underground construction making the workers and any surrounding daytrippers look puny, not unlike the little insects in Antz (1998), over which Chea has a preference, McHaffie tells me, for A Bug’s Life (1998), a film he sometimes watches ten times in a single day.

Chea lives and works in Melbourne, where his family migrated from Cambodia before he was born. Although he dreams of one day touring the US in a Cadillac, Sydney is about as far north as he’s ventured so far. Most of his work is made at Arts Project Australia, a studio complex in Northcote that has, since its establishment in 1974 by Myra Hilgendorf OAM, served as a space for artists with intellectual disabilities to practise in an environment designed to foster and supporty their artistic interests. The model of this institution, a self-proclaimed ‘centre for excellence’, allows works by over 100 artists to enter the contemporary art world through the advocacy of its staff, which includes artists like McHaffie. The framework Arts Project provides therefore ensures that the environment for the exhibition of artworks — perceived as a potential minefield for artists often unable to represent themselves (some of whom are unable to speak) — is ‘non-directive’ but necessarily important for establishing the often highly refined visual abilities of these artists in the face of a marketplace trained in exploiting novelty and artists deemed “outstanding”. The related notion of the outsider is the most obvious entry point for discussing works by Chea and other Arts Project artists, however. But following Art Brut’s advocacy for the relevance of all art practices encompassing modernity, a contemporary environment where everything is now presented as integrated, where we are told there is no longer any possibility of an ‘outside’, how these artists appear in a space that fetishises — capitalises — difference, is well worth considering. This is especially so given the collaborative remit of Radonich’s nascent gallery project; the further art can maintain itself from the reaches of ‘normal’ culture, it seems, the more distinctly it can be perceived as a legitimate entrant into an already crowded cultural space.

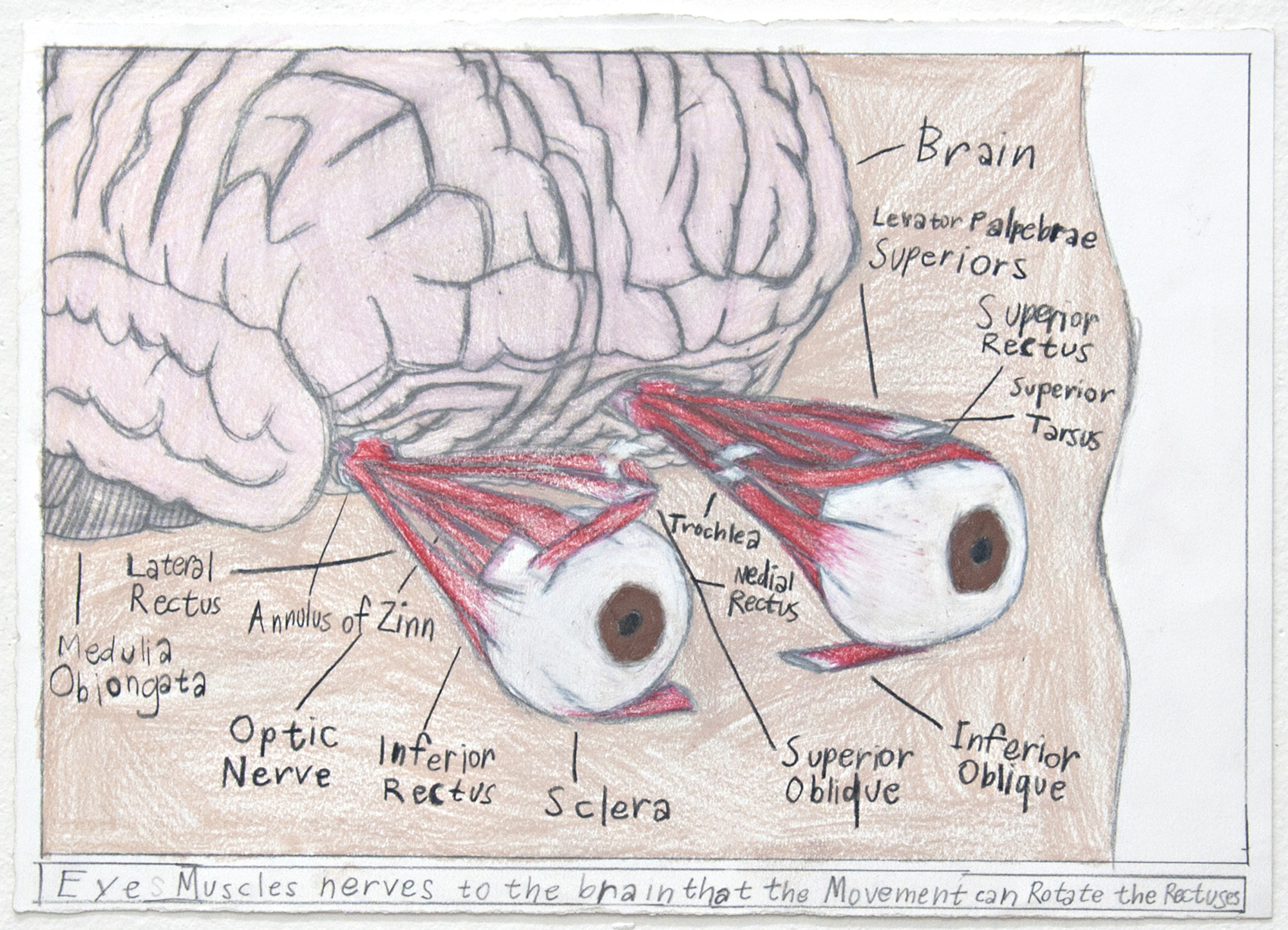

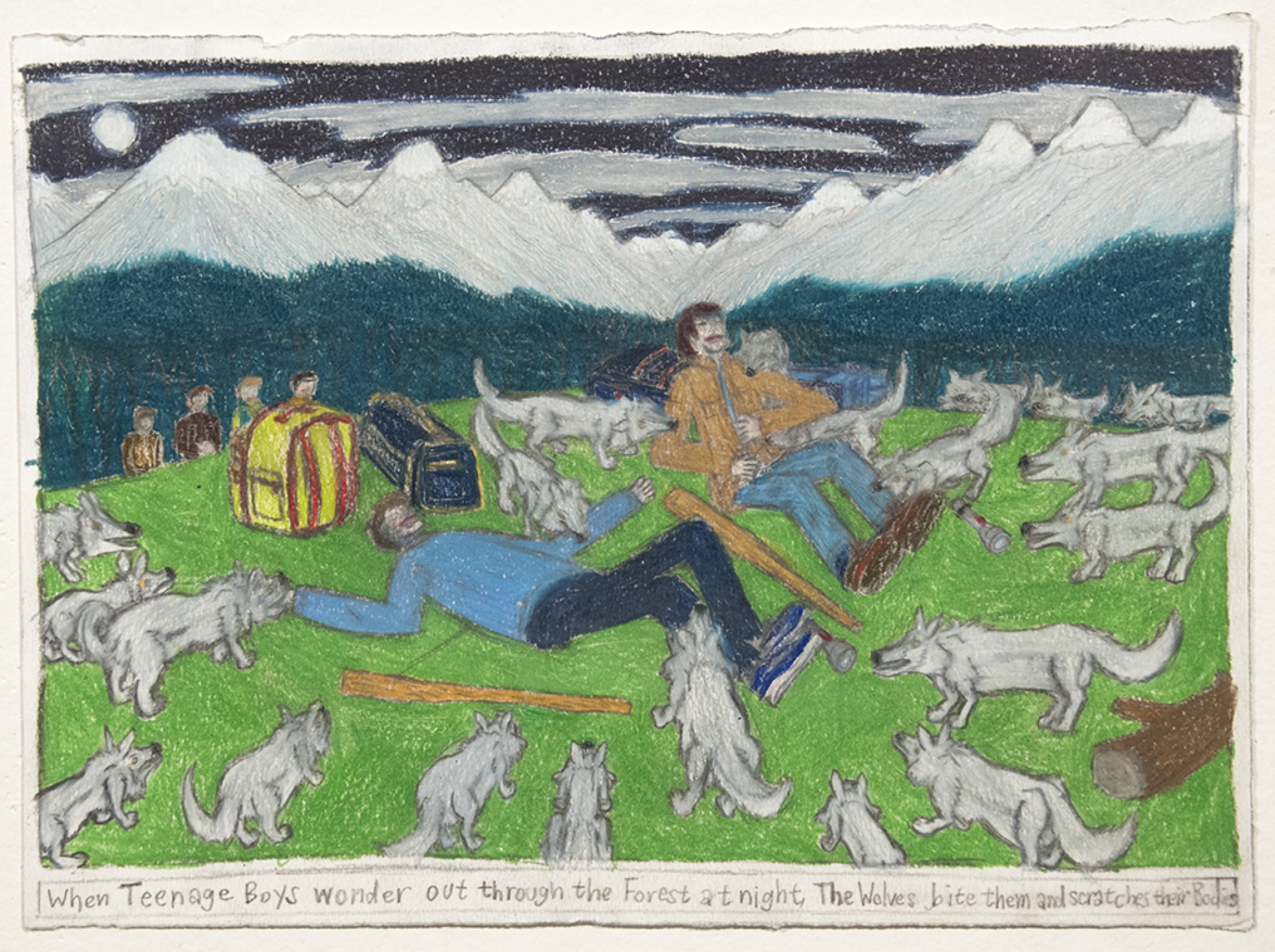

‘The outsider artist doesn’t care, or know, about any audience,’ Hal Foster proposed in a 2017 survey of contemporary art; ‘he or she (sic) has a vision, and the image or the object is there to actualise it. The viewer be damned.’ The argument that a turn to outsider art is a reaction to collaboration was a deliberate provocation. It is this kind of thinking that Radonich, by showing works by Chea which demand their exhibition to an audience, can be seen to undo. Apart from his existing artist-dedicatees, the audience for Chea’s work also includes the other works in the show; they judge each other and converse from wall to wall. This is the ‘expression surveillance’ that lies at the heart of the endeavour; it is what reveals the complexity of that which is made manifest by the laboured details and dizzying repetitions visible in all of the works. At certain points it reveals a kind of parental nightmare: teen pregnancies, elaborate attacks by co-ordinated wildlife, man-made environmental disasters. Otherwise a furious illumination of the militarised and regimented control societies of the present are also detectable in many of Chea’s images. One work is a sclerotic explosion of the visual organ itself: Eyes Muscles Nerves to the Brain that the Movement can Rotate the Rectuses (2014). It’s as if Chea’s fascination with visual culture reaches scientific levels of reflection here, before returning to the imagined, remembered and reconfigured scenes from manga animations and films about heroes and villains.

After exhibiting a 1963 proposal by Simone Forti, Onion Walk, alongside a video documentation of her News Animation performance as the first show at Reading Room, Radonich sets up a dialogue between the illusion of participation and the seemingly indifferent work of an artist whose interest or even awareness of the contemporary art world is minimal in a way that directly opposes that sixties evacuation of art’s contents into the artworld environment and the collective social body. Rather Chea’s show follows this opening exhibition of a videoed gesture by Simone Forti, and the single work in Room 1 of the gallery - a poem made by placing a sprouting red onion on a bottle, waiting for it to fall - as an alternative response to art as social practice. The text accompanying the exhibition falls neatly between these themes, as well as those separating the two rooms in Chea’s show. An unfinished work, Every Truckers Enjoy Having Barbecue to Eat for Picnic, Where They Sit outside near the Truck Stop During Recreation, is partly coloured-in yet still mostly in monochrome. It is this work, not on view in the show, that Chea worked on at Arts Project as the exhibition dates approached, encapsulating the determination of the artist for Griffiths and McHaffie who write about it in their text. Chea will just as easily spend months completing a work in the Northcote studio, which, due to health issues and funding problems, he can only come to once a week these days. Otherwise, working at home on these series, which sometimes recall the illustrations of Robert Crumb and at others the almost comical configurations of Phillip Guston’s interiors, is what Chea will continue to do regardless, it seems, endlessly cycling between his laptop and the empty page.

Heaven is a Traffic Jam on the 405 is the name of the film about the artist Mindy Alper, which was this month announced as the winner of an Academy Award for the best documentary short of 2017. A film about an artist suffering severe mental disorder and her redemption narrative as ‘tortured and brilliant’, as an artist who is now represented by ‘one of Los Angeles top galleries’, if nothing more, reveals how intimately linked art and mental health still are in the modernist vernacular of excellence. In his unfinished work, Aesthetic Theory, Theodor Adorno characterised the artist figure in the West in the following way: ‘Those who produce important artworks are not demigods but fallible, often neurotic and damaged, individuals.’ As such, he argued that the element of truth that can be ascribed to the artwork is to be found in the object, its genius not a question of subjectivity but rather its appearance.

Chea’s work appears without the figure of the artist. Rather, it is the remains of his uncompromising artistic activity that have been gathered as documents of his practice at Reading Room. The title alone speaks of the coy ambition of a work that pertains to questions which troubled those like Adorno, who sought to penetrate to the heart of modernity’s apparent crisis in representation. Downstairs on level 3, at World Food Books, two works by Susan Te Kahurangi King dating from the 1960s are showing in the climate of contemporary art’s sudden desire to re-engage works by artists from ‘outside’ this idea of arts as industry. The intensity of the colour and line in the drawings allows for a correspondence with the artist upstairs to open up in time, and yet remind us how universal the images of Donald Duck, or the Titanic disaster, are for our collective imagination.

In proximity to the National Gallery of Victoria, which reportedly installed and then promptly disposed of $12,000 worth of flooring to appease an artist having a pre-opening flutter at the Triennial, Reading Room operates at the other end of the scale, aiming to make its limited resources go a long way. Arts Project, like the NGV (which has acquired works by Arts Project artists), operates largely through public funding provided by federal and state governments; its commitment to enabling artists relies on the state for its continuing support of talented, yet under-resourced and disabled artists such as Chea, as opposed to relatively humble prices for the sale of their works. The idea of the exhibition in its humble ambition is therefore respectful of the fact that large numbers of artists are forced to work within very limited means, while others are given the lottery of a blank cheque. Chea’s work – saturated as it is by the films that he loves – perhaps ultimately proves Jean Cocteau’s prediction for the cinema: that film may only become an artwork when it is inexpensive as pencil and paper.

Giles is a writer and musician working at Monash University and the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.