Elvis: Direct from Graceland

Giles Fielke

Is Elvis a figure of history or of memory? From the position of the latter is from where I have come to understand the significance of the musician and entertainer; actor and performer; lightning rod; tiger. He is the embodiment of mid-century USA’s best and worst characteristics; he is the King. Born Elvis Aaron Presley in Tupelo, Mississippi in 1935, he is only a few years older than Bob Dylan and the Beatles. The history of his life has been re-told many times; there are nearly 600 books on my university library catalogue that appear in a search for his name. Yet by memory I mean the “Elvis Big Band” and their forty-fifth anniversary spectacular stopping at the Thornbury Theatre in July this year. It is Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds singing ‘Tupelo!’ It is Baz Lurhmann’s newest production—shot at the Village studios on the Gold Coast during the pandemic lockdowns and opening on Australian screens in two weeks’ time—starring Austin Butler as Presley and Tom Hanks as his manager, Colonel Tom Parker. It is Lana Del Rey LARPing as Priscilla Presley, who married Elvis in 1967 (after meeting him in Germany when she was just fourteen). It is the Addams Family (which started in 1938 as a New Yorker cartoon, so is technically Elvis’ younger sibling). It’s Grease. It is the Elvis shrine at the Carlton Cemetery that is more like a grotto and therefore a syncretic Christian-Pop-Pagan portal to an underworld deified by formerly real people: figures from history, mythopoeic beings made memorious titans, stars. It is Elvis: Direct from Graceland, the exhibition at the Bendigo Art Gallery (BAG). As writer and rock critic Greil Marcus nimbly elucidated after Elvis’ death in 1977: “Elvis’ presence was so powerful… he’s always in the present tense”.

On my approach (I’m walking from Bendigo train station), it is evident the city is amidst the grip of an Elvis maelstrom. There is the usual blockbuster exhibition giveaway: serial flag-pole advertisements are out in full, but there is also an Elvis-themed shuttle bus in operation up and down View Street. Opposite the Alexandra Fountain, there is a forcefully redundant “Viva Bendigo” installation that seems to be piping Elvis’ music 24/7 into the wintry ether. Priscilla Presley had flown in to open the show and perform VIP duties earlier in March. Now, in June, the numerous Elvis cut-outs and related ephemera on display in Bendigo’s shopfronts appear dusty and even somewhat faded, yet they suggest the city’s storeowners’ apparently wilful approval of the exhibition. I wandered into the guitar store across the road from the gallery; a Ukulele is set up to strum an A-chord when someone opens the door. “It’s not really my thing”, states the shop attendant when I ask about the Elvis display in their front window, and gestures to the flashing golden entrance to BAG out the window. “I won’t be going”. When I order a coffee at Walker’s Doughnuts later in the day, the barista tells me she’s been to America twice and has already seen all of the Elvis gear at Graceland. She doesn’t need to see it here. At the first sip of coffee a layer of skin is stripped from the upper palate of my mouth.

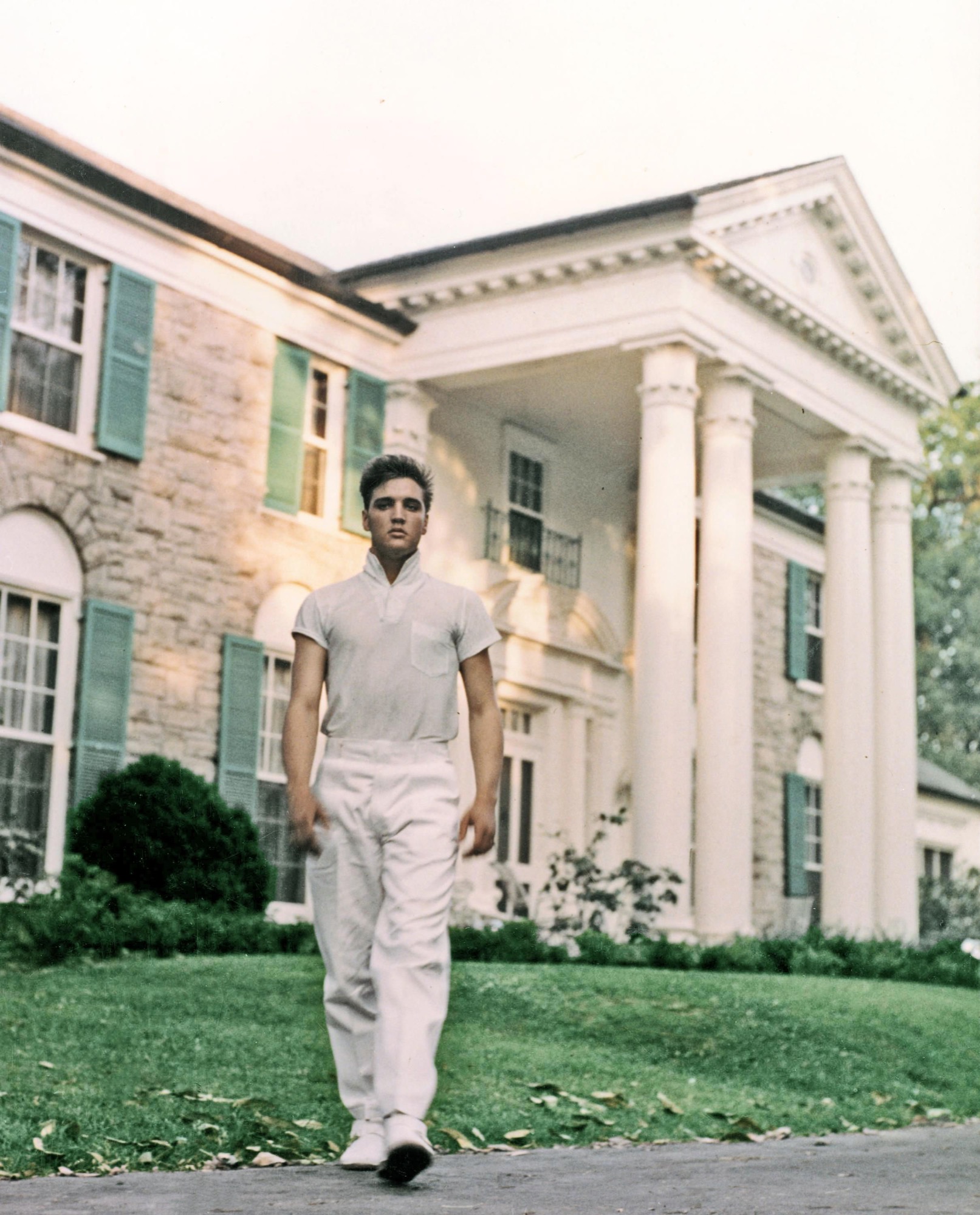

When the urban historian Asa Briggs visited Australia from England in the 1960s, he realised while walking around Melbourne and looking at it that he was seeing a British city on the other side of the world. Bendigo is this, even more so today. In Briggs’ 1963 book, Victorian Cities, he looks at London, Birmingham, Middlesborough, Manchester and Melbourne, the only non-British city in the book. Briggs writes that in Melbourne you have a Victorian city that’s been transplanted to the other side of the world and you see many of the features you would expect in Northern British cities like Manchester or Liverpool there. If you have been to Manchester or Liverpool, you will also get this sense of déjà vu visiting Bendigo, because it too is very much a Victorian city. This incongruity gives the appearance of Graceland within the gallery a strange sense of competition for sovereignty: art or culture, history or memory? These distinctions remain unresolved, symbolised perhaps by the neo-classical sculptures that line the exit to the exhibit. As are part of the Gallery’s permanent collection they are in no-way synchronous with Graceland’s US colonial-classical eclecticism (even if the gallery café has adopted a Southern-style menu for the duration of the show).

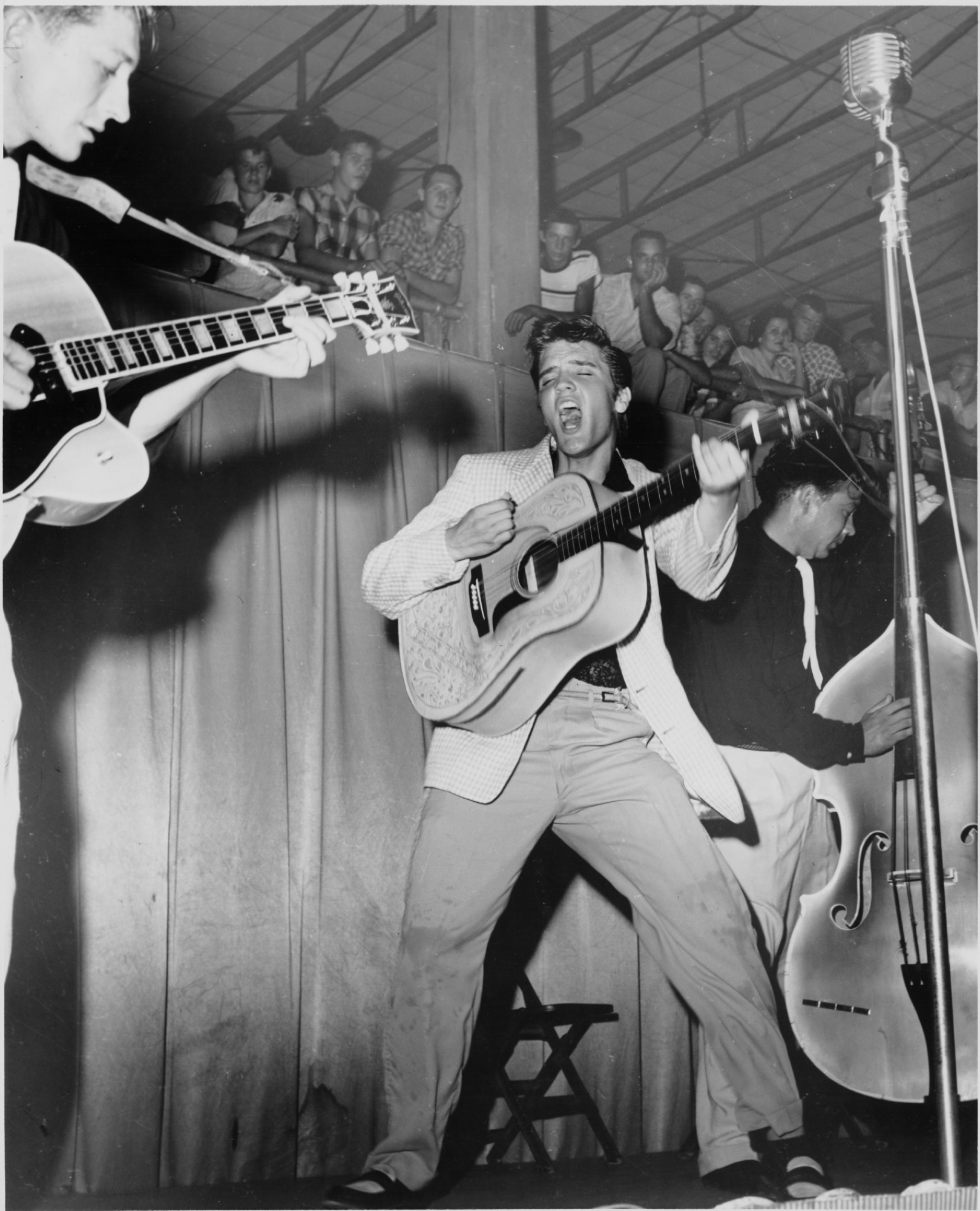

Until now, the closest I’d ever been to Elvis was over a decade ago. The Melbourne front-man and Double J DJ Henry Wagons was performing Rocky Erickson’s ‘You Don’t Love Me Yet’ at the Toff in Town. He walked off stage and placed his finger onto the centre of the poet Eva Birch’s forehead. I witnessed this from the next table, and while he sang ‘Wagons’ stared directly into her eyes. The spontaneous connection was momentarily powerful; there is an undeniably libidinal electricity to the spectacle of an amplified performer breaking the fourth wall (coincidentally—or not—Wagons is scheduled to speak about Elvis at the BAG on the 23 June). In the 1950s, Elvis, harnessing the power of radio, broadcast his own body; his voice was deemed dangerously sexual. Today the electricity feels unchallenged, quotidian. Maybe all our libidinal energy has actually left our bodies, the electrical amplification of our voices now stored in lithium batteries.

Inside the galleries, I am instantly immersed in Elvisified tchotchkes: his childhood crayon deck, telegrams to managers, the actual keys to Graceland (quaintly unremarkable door-keys), a restored and inexplicable ceramic cockatoo he kept in the den at Graceland—as proven by a small black and white photograph behind it. A golden telephone, an American Express Card. I’m reminded that The Philosophy of Andy Warhol is contemporary with Elvis at the height of his second-coming in Las Vegas: “buying is much more American than thinking”. There is an immediate and palpable melancholia in the rigorous exploitation of everything and anything Elvis touched. Even his life membership to the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, at which he performed six shows over three days from the first of March 1970, is on display. There is nothing so banal that Elvis’ auratic penetration cannot make fascinating.

To go to Graceland, is therefore to experience modern divinity. This is the key problem for BAG. It is not Memphis. It is not even gospel. Yet the pilgrimage required for BAG’s sometimes four thousand visitors in a day (an attendant tells me Saturdays are mental) relies on a carefully-honed machine that emanates not from Elvis, but from Priscilla, who co-founded Elvis Presley Enterprises (EPE) in 1982. Despite their divorce in 1973, the surviving Presleys opened Graceland to the public exactly forty years ago to the day of my writing this review on the bus home. Untangling the vertiginous career of a teenaged singer who paid four dollars to cut a record at Sun Records in 1953, dedicated to his mother, and who died not quite a quarter of a century later in 1977 as the highest selling solo musical artist of all time, is mind-boggling in its complexity. From Hollywood to Las Vegas, via conscription into the US Army, Elvis was always a marketing juggernaut. But it is the contemporary iteration of the undying Elvis that is most fascinating. Elvis on record is the arch-promiscuity of reproducible, cheap media like 45s and 33s (one framed record on display celebrates the two-billionth Elvis record pressed at RCA, ‘Moody Blue’ in 1977, which is clearly a massive over-exaggeration). The undead Elvis, programmed by Priscilla, simply plonks his red 1960 MG convertible into the centre of a gallery (which eager pilgrims can’t resist attempting to touch) and, just like that, he is in the room with us right now.

The show itself is replete with set-designed daises and vitrines that use the museum form to divide the eight galleries up into narrative chapters such as Hayride to Hollywood, or ‘68 Special. The installation is fully integrated, the aural relentlessly interacting with the visual to immerse viewers entirely within the Elvis universe. So much is familiar to me, without feeling like I have consciously seen any of it before, that it is hard not to feel crushed by the weight of such a magnetic star, or do I mean a black hole? Post World War II US-aesthetics are so fucking weird. It is like gaping at a carnival ride but from within, and one that you’re never allowed to get off.

Joel Weinshanker—founder and owner of National Entertainment Collectibles Association and now also Rubies One World costumes—is named in the exhibition text as the majority owner of EPE today. Weinshanker’s businesses hold the licenses to sell merchandise from entertainment companies like Marvel and Disney, among any number of US culture factories. I realised this is key. While there is not a US flag to be found in the exhibition, Elvis’ patriotism is un-paralleled (he only performed in three cities outside of the US, ever: Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver). There is a letter from President Nixon (a photograph of them together is the most requested document from the US National Archives, according to historian Mathias Haüssler), and various US Army ephemera from his service in Germany in the late 1950s (when he was already a star back home). But Elvis’ strange mix of new cultural corruption on the airwaves and patriotic military discipline in the wake of the Army-McCarthy Hearings is evidenced more in the sincerity of his endeavors. This alchemical combination was formulated by his marketing genius manager ‘Colonel’ Tom Parker, who snatched Elvis’ contract from Sun Records and brought the heartthrob to RCA Victor in 1955. A year earlier The Blue Moon Boys’ release of the Black blues singer Arthur Crudup’s ‘That’s All Right Mama’ had catapulted Elvis into the spotlight. Crudup, also born in Mississippi, but three decades before Elvis, stopped recording in the 1950s, stating: “I realized I was making everybody rich, and here I was poor”.

Elvis would never experience the music industry in that way: “The fans want my shirt. They can have my shirt. They put it on my back”. The sartorial significance of this metaphor is central to the Bendigo exhibition, and is highlighted by the curator, Lauren (Lola) Ellis. If you lean in close enough, you can actually smell the nylon, you can even see through the slippery glimmer of the rhinestones on those gilded capes and jumpsuits. The weird orientalism of post-World War II, middle-America is hastily glossed over by the sheer weight of the items on display (Karate gi was imported into the US-vernacular by GIs stationed in Japan, and Elvis took it up in Germany and Paris). Gallery Director, Jessica Bridgefoot, places the show squarely in line with other recent exhibitions, dedicated to fashion and popular culture: Marilyn Monroe, Grace Kelly, Balenciaga and Mary Quant. The idea here seems to be that design mediates all elements of the museum space, and while the contemporary definition of art is anything that people will pay to see, the trick is to pander to populism as a way to quell any sense that art is elitist.

As such, the King’s iconic garments and their designers, particularly Bill Belew, occupy a central role in the myth perpetuation of Direct from Graceland. Really, Belew is the secret star of the show. Supposedly inspired by Napoleonic fashion, his sketches for Elvis buttress the exhibition, which allows the viewers to witness the formation and creation of a pop star character in a way that mirrors the emergence of Batman in DC Comics or Marvel Comics’ formulaic super-verse—both of which began in the 1930s in the same decade as Presley’s birth. This is the vision Weinshanker has perfected, and it is Priscilla who appears to have connected the dots (lots more could be said about her posthumous relationship with her ex.) Today it makes so much sense to link Graceland to the franchises that enjoy blockbuster success that it is unclear to me whether most of the visitors to the exhibition are even Elvis fans, or even know the names of his most famous songs. Elvis became a real-life Marvel figure in death but always in the present tense.

Given the centrality of garments to the exhibition, where is Elvis’ Nudie Suit? Why was it left behind at Graceland? The eccentric designer who created the West Coast pop-country aesthetic, Nudie Cohn, was actually born in Kyiv in 1902, within the Russian Empire that Vladimir Putin is violently attempting to rebirth today. Cohn made rhinestone suits famous in the 1950s and eventually made Elvis’ famous gold lamé suit in 1957. Nudie suits were also made for Ronald Reagan and Gram Parsons. Yet while Cohn’s suit is not in the exhibition at Bendigo, a vast number of Bill Belew suits are. The insane American Eagle suit offsets the red MG car, anchoring the two extremes of the exhibit: industry and esoteric mysticism. In a recent interview Belew talks about how Versace was jealous of his gig dressing Elvis. Seen through an Italian neo-Baroque lens, Elvis makes perfect sense in this moment of late-capitalist camp. (Donald Trump makes sense after witnessing Elvis). While the exhibit is all spectacle, glitz, and chintz, it’s also a sleight of hand. Where is the darkness, the pathos exemplified in the gospel-inspired gems like the 1969 hit ‘In the Ghetto’? Where is the throne upon which the bloated and calcified Elvis died?

Elvis is the exact centre of a pop culture universe in which only the US exists, it is Memphis (the resting place of pharaohs too). If Michael Jackson was the first person to live in the twenty-first century, Elvis was the first to live in the twentieth century. He returned to Graceland after his marriage to Priscilla in Las Vegas on May Day in 1967. Lisa Marie Presley was born in Memphis exactly nine months later, on the 1st of February. Two months later, Martin Luther King was murdered there. Lisa Marie would marry Michael Jackson in 1992, whom she first met when she was seven. Jackson really is the closest comparison one could make to Elvis in terms of their pop-mythos stature.

Elvis Aaron Presley was born a twin in a wooden shack at the end of the Great Depression. His brother Jessie was stillborn. There is a Promethean arc to Elvis’ career. His death in 1977 still feels gross and tragic, even today. He is condemned, it seems, to spend his undead eternity splashed on walls in front of the eyes of museum spectators with mouths agape. Yet Elvis’ motto, TCB (taking care of business), is also the enduring symbol of Melbourne’s progressive artist-run space. The first time as tragedy, the second as farce. It seems Elvis’ appeal still cuts both ways: avant-garde and kitsch. In September, I’m heading to Memphis. Tupelo is just down the road, across the state lines into Mississippi. Perhaps I will endeavour to prostrate myself at the tomb of our collective twentieth century father-son and holy ghost, Elvis. America.

Giles Fielke is a lecturer at Monash University and an editor of Memo Review.