Elizabeth Pulie: #117 (Survey)

Ann Stephen

Elizabeth Pulie’s exhibition at UNSW Galleries reveals a brilliant feminist/feminine/female practice shaped in the wake of 1980s post-modern Sydney. Over the following three decades the artist has been driven by ontological doubt to operate on several distinct levels of practice, and at key junctures to make dramatic shifts in her own work to signal another way of going on. The exhibition, entitled #117 (Survey) and curated by James Gatt, eloquently lays out these moves in detail for the first time. Beginning in the foyer, the exhibition carves Pulie’s oeuvre into three distinct streams, which are then each separately elaborated in the three main gallery spaces. Her survey, the second of the University’s biennial art commissions after the remarkable Archie Moore project in 2020, is an initiative of the gallery director, José Da Silva, to support outstanding mid-career artists. Pulie’s new commission extends beyond the exhibition to include a new video work and a reader, compiling the artist’s significant body of writing from 2001–20.

Decorative Painting: 1988–99

As an artist, I’ve attempted to deal with Warhol’s question—”What can we do for Art?”—in different ways.

— Elizabeth Pulie, 2014

The first and largest gallery displays Pulie’s Decorative Painting series (1988–99), and is divided along its axis by a long slim table topped with some fifty-eight decoratively painted panels laid flat like tiles or plates, entitled Small Paintings (1995). The surrounding walls read like scaled-up pages of Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament, an 1856 handbook of the decorative that Pulie continues into the twentieth century. For instance, one canvas is based on a 1950s abstract pattern from the ‘moderne age’ with flat linear boomerangs in dirty, acid colours. It’s a reminder that in Australia abstraction was only popularly embraced by design, a spiky domestic version of modernism.

Another much larger vertical-format painting has a field of pastel stripes in yellow and aqua, covered by red and blue floral ornaments and spots all ringed in black, like over-sized kitsch wallpaper—a sideways glance at Pulie’s aesthetic “god-father”, Andy Warhol. Yet unlike the multiple silkscreen prints and wallpapers of Andy’s Factory, Pulie individually executes each canvas or board with dexterity and precision. Nonetheless, there is nothing tasteful in Pulie’s catalogue of the decorative, rather it is full of incongruous juxtapositions that test and tease the viewer’s own taste. Take the two black-ground gold-trimmed flowery patterns derived from a central European folkloric knick-knack and enlarged to canvas—something even Warhol, the son of Slovak émigrés, would not have touched.

Pulie’s tour de force, Decorated Wall (1995), covers the gallery’s far wall. Consisting of twenty-five closely abutted canvases, the work casts the ornate patterns of the Versailles court—a riot of arabesques, tear drops, floral sprays, dolphins and blue birds each immaculately formed with highlights in two or three tones—as symmetrical, highly stylised formal devices. As a precocious student who came of age in the era of the “end of painting” and “the critique of originality”, Pulie found in the abject ornamental the possibility of a feminine abstraction, which she mimicked to hallucinatory effect.

Gatt reports in a fascinating accompanying essay that Pulie regarded her Decorative Paintings project as “a failure”, because “its intended criticality was absorbed by the art world, with paintings curated into institutional exhibitions and collected by museums”. The curator goes on to argue that this, however, could be taken as a sign of the project’s “success, highlighting the fine line Pulie walks between her participation in and critique of art”. Whether it’s possible to have your cake and eat it too: such dilemmas were familiar to the first generation of conceptual artists. Pulie confronted this same dilemma in 1995 at the age of just twenty-seven, when Decorated Wall was acquired by the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Relational Art: 2002–06

This notion of working outside institutions…is doomed to failure.

— Elizabeth Pulie, 2005.

At the millennial turn, the ground shifted for Pulie and, like many “post-conceptual” artists, she sought to move away from the production of objects to instead create dialogical spaces for new forms of life, a mode of art-making famously described by Nicolas Bourriaud as “relational aesthetics”. Pulie transformed her own living space, opening her lounge for artists to exhibit in what she called the Front Room gallery, later extended to what became known as the Kitchen. Then, beginning in 2001, she began to review and interview artists and to self-publish a magazine titled Lives of the Artists. Pulie’s po-faced approach, more Warhol than Vasari, surveyed the range of Sydney artist-run spaces and their artists, including Justin Trendall, ADS Donaldson, Sarah Goffman, Maria Cruz, Billy Gruner, Ian Milliss, Jonny Niesche, Robert Pulie and many others.

It is always a challenge to exhibit such social and political practices, as their anti-institutional intent sits in opposition to the museum. Ephemeral sheets of paper and dialogue do not translate readily into visual spectacle. While Pulie continued to make and exhibit objects—some of her drawings, paintings and a wonderful bead curtain, from the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, are salon hung at one end of the gallery’s second space—her Relational Art project is represented most effectively in the survey by the publication of her Reader. Several copies of this are placed on a table (from the Kitchen) between two chairs, with a recording of the artist in conversation with the curator. The Reader requires its own review, being a substantial critical document of forty-three entries. All her writing is organised chronologically, with each reprinted in its original typographical format. While Pulie makes minimal editorial commentaries in the interviews, she probes many crucial questions in a collection of her own texts beginning in 2014 comprising fourteen impressive essays. As she explains in the Preface, it reflects the goal of the entire exhibition “to emphasise a sense of an artist’s practice, or the entirety of the objects of their practice, as one work, one concern, one train of thought, and to exemplify the notion of such practice as discursive”.

End of Art: 2012–ongoing

Rather than strive for a break with the modern, it may be more effective here to theorise contemporary art in relation to the modern, to view it as an effect, outcome or continuation of modernity than something altogether new.

— Elizabeth Pulie, 2020

Pulie announced her return to first-degree art making in 2012 with the End of Art project, tangling with the implications of Ad Reinhardt’s modernist dictum, “art as art”. The project began with paintings on linen, canvas and even doors before moving onto a series of Female Form hessian banners whose rough, brown threads are more at home as sacks than as canvas. Like Tom Nicholson’s banners, they carry no slogans. Pulie’s are instead adorned with a familiar repertoire of ornate pattern-making celebrating a women’s culture of ornament and “centre-core imagery” (a second-wave feminist art term for the typology of wombs and vaginas). The series is amongst her major works, and it is only here that the limits of the UNSW galleries are visible, as the low ceiling height does no justice to their grand scale—one even trails onto the floor. Ultimately, however, the floor is no bad place for Pulie, whose Matrix Revisited floor piece is a square hessian rug complete with a fringe of tassels, made up of four symmetrical geometric units formed by straight lines, painted in black. The abject material of hessian returns as a carpet that lays out the fundamental grammar of geometric abstraction.

Several of Pulie’s Bauhaus Weaving series, first exhibited in Buxton’s Bauhaus Now! in 2019 (which I should say, I curated), question the gendering of work. As I wrote at the time, “her work can be seen as a response to the challenge of medium specificity, using the criteria of one media (painting) to define the parameters of another (weaving)”. Pulie had taught herself to weave on a hand-loom and studied the modernist textiles of Bauhaus women artists. These largely bodily-referenced works mix mostly monochrome hessian with recycled clothing, though several have internally complex surfaces, embroidered, pulled and adorned with beading. The humble and the majestic meet in a dialectical dance to the end of art.

Heaven in Love

I like art that declares a void, not indicating a world beyond or behind itself—perhaps containing the world within itself.

— Elizabeth Pulie, 2014

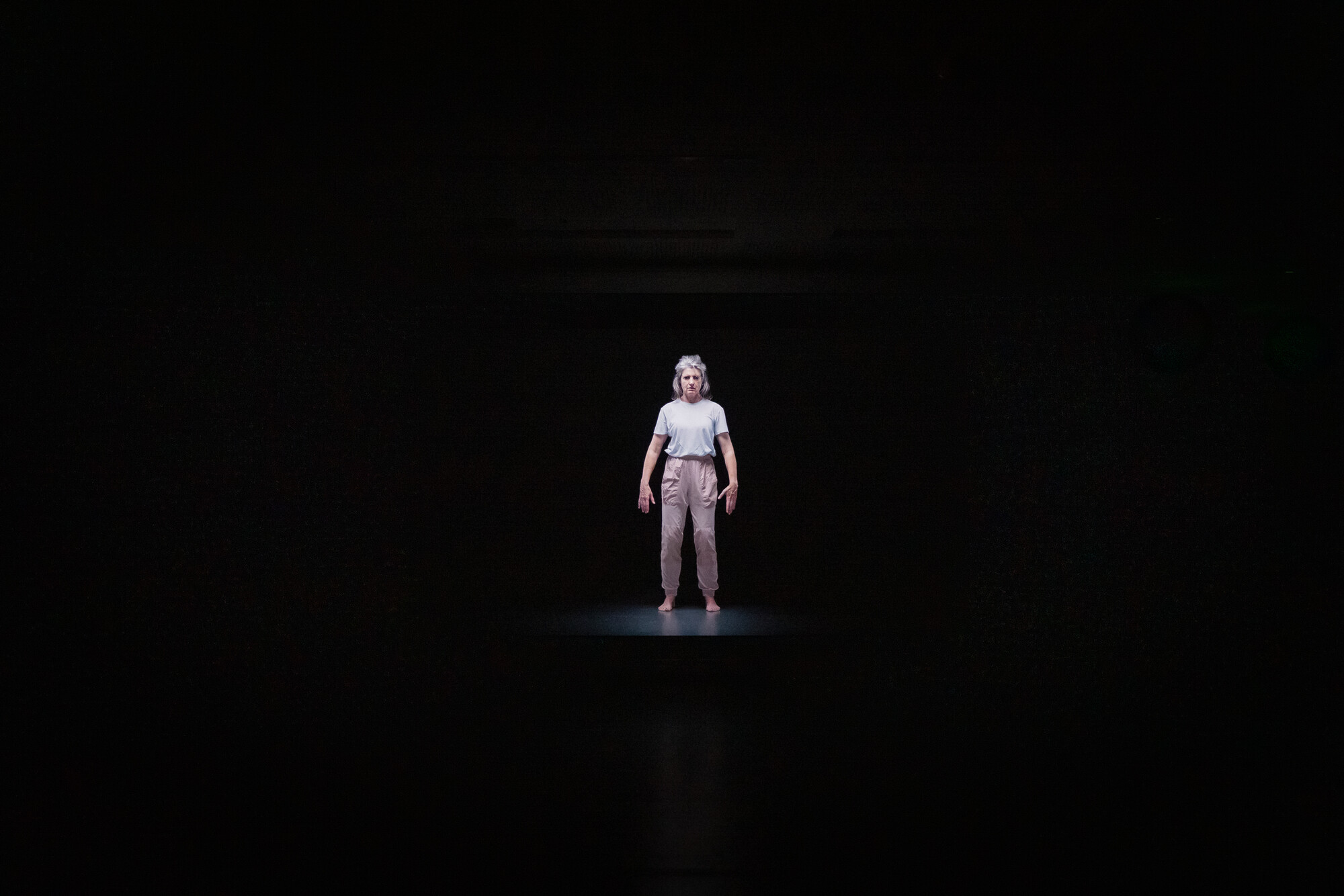

The final room at UNSW projects a short video loop, #118 (Heaven in Love), onto a full screen wall. Against a black space, the barefoot figure of the artist in pale t-shirt and pants performs a slow mesmerising series of hand movements that shape the air, keeping her feet fixed to the ground. She appears to move in slow-motion up and down, following the trace of her hands. The artist is fully absorbed, her gaze is inward and only attends to her own movement, not the spectator. The camera moves from full-frame to close-up, in rhythm with her breath. Gatt suggests that this surprising shift “functions as a musing on what it means to make art and be an artist contemporaneously, both in the sense of occupying present time, and practicing in the current period of contemporary art…it also represents a trajectory through Pulie’s art practice from highly productive states of making art objects to deliberately unyielding routines of movement that instead focus on being”. His statement is underpinned by Pulie’s own considerable critical writing that ambitiously debates what it means to be contemporary as a post-conceptual artist.

Ann Stephen is a curator/art historian/writer at the University of Sydney.