Elizabeth Gower, LOCATIONS

Chelsea Hopper

Elizabeth Gower has always had a knack for sourcing material. As a young artist, she once nicked an entire ream of butcher's paper from a fish and chip shop. What began as a failed endeavour as the paper buckled when Gower painted onto it, led her to tear it up, weave the strips of paper and reassemble it as the paper quickly became the work itself instead of the canvas for another work. Gower's interest in paper collage has been sustained in her artistic practice for over forty years with all the material she uses being found (or, in at least one case, stolen).

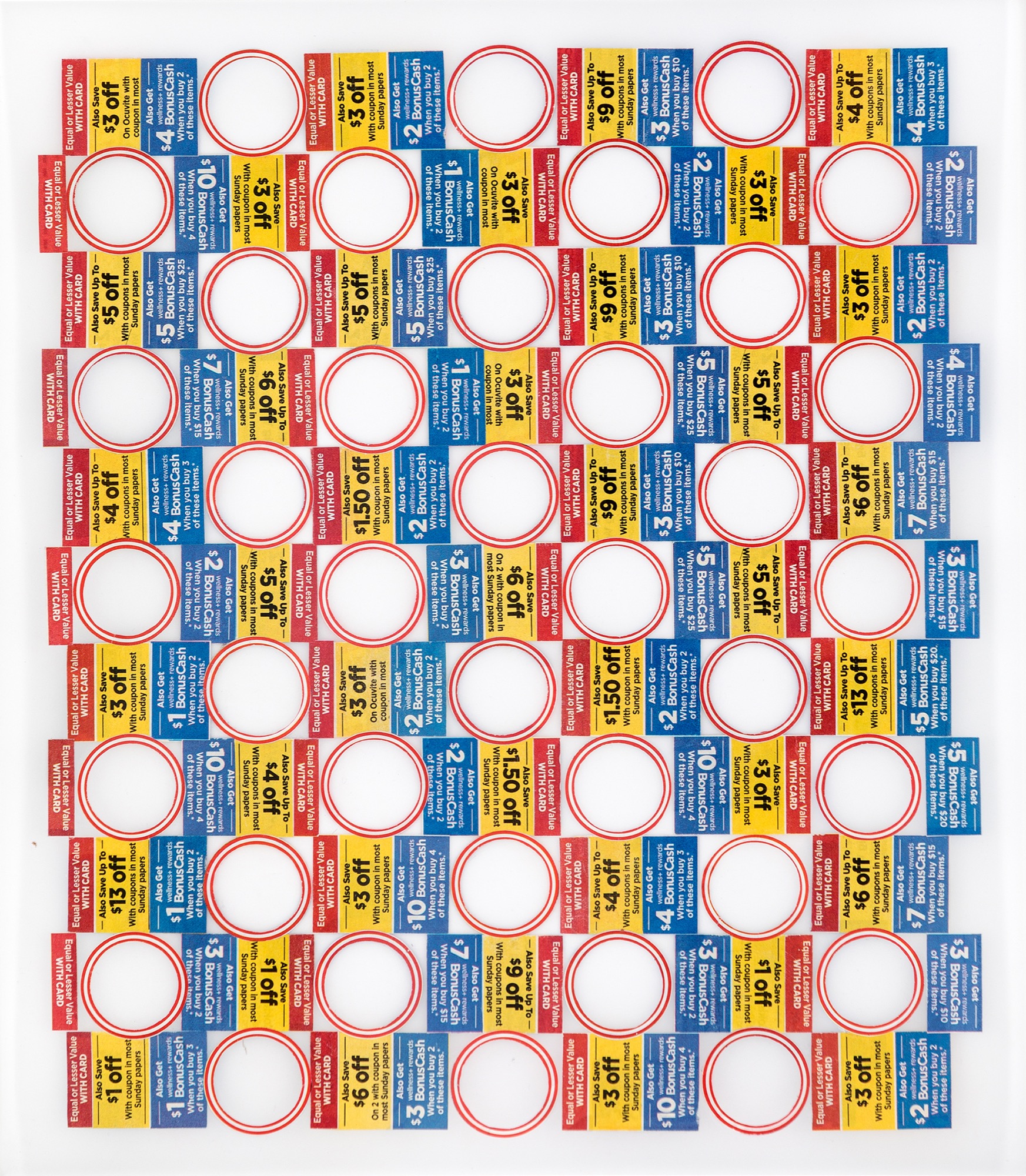

In the early 1980s, when Gower moved into a studio located in Melbourne's CBD, she collected found paper, posters, packaging, billboards, magazine ads and racked the newspaper headlines propped outside of local newsagencies. The bombardment of junk mail that spilled out of apartment blocks and residential letterboxes soon found a home in Gower's studio. Every scrap was either stored away or utilised in her collages as the fragmented and disjointed pieces were cut up, rearranged and put back together again. The bold colours and imagery of the cheap advertising was enticing, and can be seen in her seven framed collages, City Series (1982), currently on show at Sutton Gallery and Sutton Projects exhibition LOCATIONS.

The most recent series of collages line the walls of Sutton's main gallery space and were completed during Gower's travels between residencies and exhibitions in Assisi, Athens, Berlin, Malaga, London, Edinburgh, New York and Collingwood, over a six-month period in 2019. In these works, Gower uses sheets of drafting film—a thin, malleable paper stock—as the base for each of the small, neat, paper-cut collages. The material affords Gower a certain ease, both in providing such sizeable quantities and through its lightweight nature, which is conveniently compactable (Gower appears continuously on the move).

Each of the twenty-four collages in In Transit Collages (2019) is sourced from packaging and printed matter repurposed, cut up, rearranged and assembled to produce a set of geometric compositions. Different types of teabag brands from Rabea to Lord Nelson are one of a few identifiable sources found within the configurations. Along with the familiar Coles supermarket sale price tags and Chemist Warehouse advertising that champions a discount strategy paradox to “buy more to save”. Gower utilises symmetry and repetition, often giving the collages the impression of movement in their pattern and formations. Silhouettes of objects like diamond rings and gold and silver Rolex bands create a rhythm, and a kind of abstract language to produce an order among the chaos.

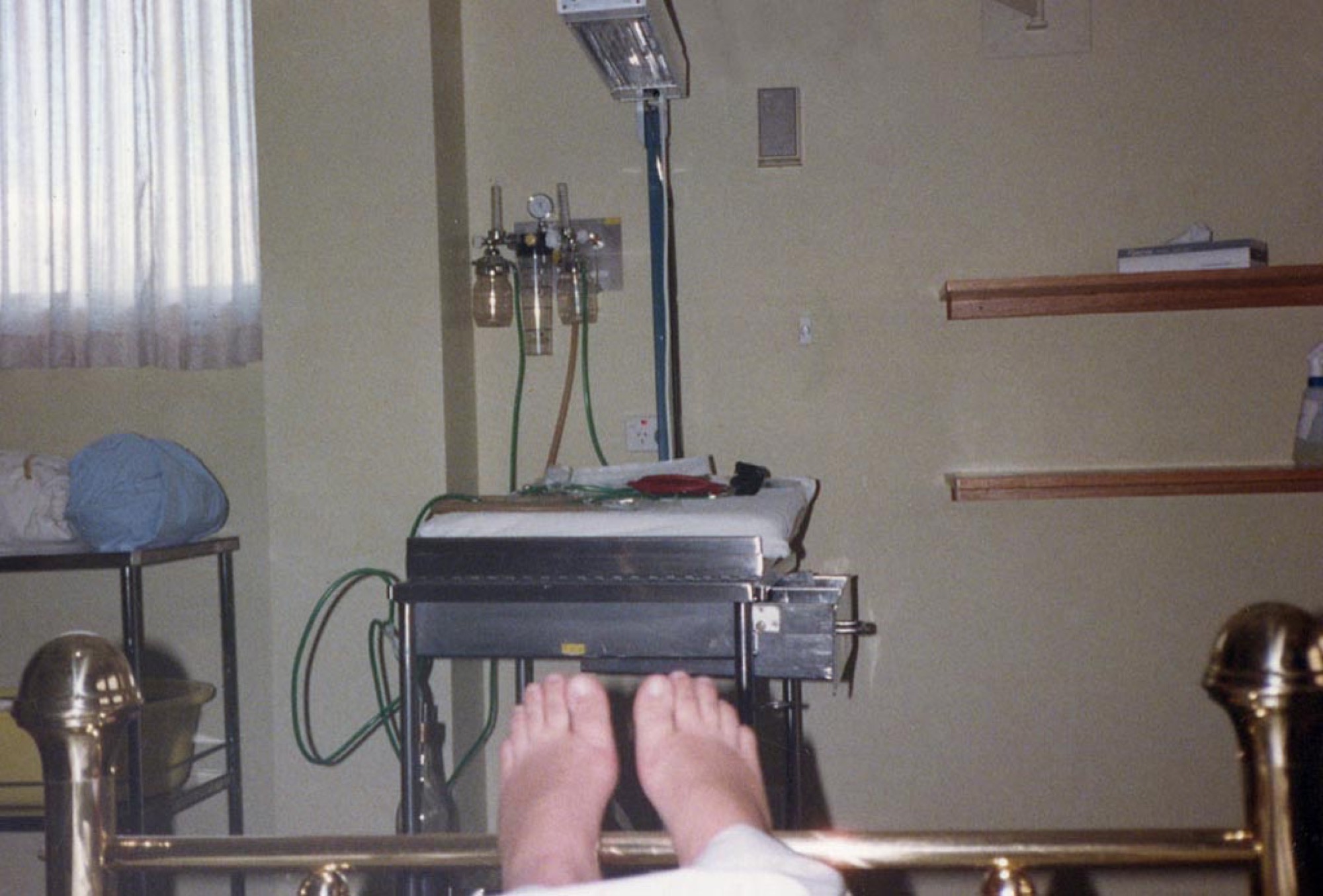

Around the corner in Sutton's Project Space is Places (1980-2020) a collection of 250 colour photographs split into seven long rows is wrapped around the gallery's wall, depicting Gower's feet standing and, at times, lying down in various places over the past forty-years. Below each photograph, a line of text annotates the location and year her feet and, of course, Gower herself, have traversed cities around the world: Kassel, Dubai, Venice, Barcelona, Brooklyn, Brisbane, Hong Kong, Hobart, Rome, just to name a few. Longer stints can also be identified: London, New York and the Melbourne suburb Collingwood, where Gower has a studio.

(image: image5.jpg caption: Elizabeth Gower, Outside Uffizi Gallery, Florence 1983, from Places (1980 – 2020) series, photographs, dimensions variable. Image credit: Courtesy of the artist.)

Although the series spans a four-decade period, Gower's chosen subject matter strictly denies us the opportunity to see the passing of time in an overt way—her feet do not reveal the aging process the same way a face does. Portrait of an Artist as a Woman (1974 – present), for example, is an ongoing series of photographs of Gower taken in front of her artworks. It exposes (among many things) distinct changes in her age over a lifetime: from distinctive hair styles and fashion choices, to a chronological progression of her own artworks' form and content. Sue Ford's Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006)(2008) also comes to mind—47 self-portraits taken over her lifetime equally draw our attention to the strict relationship tied between photography and time and the camera's innate ability to allow us to “see” it.

As each print is labelled with place and date, it's an effortless task to contextualise the images. Yet other indicators are forged within the series, connecting it to the history of photographic technology as well as the evolution of footwear. Images from the 80s appear slightly grainy or washed out due perhaps to the quality of film or the type of analogue camera Gower would have used at the time—regulated by precarious manual film camera settings. The colour of the prints from the early 90s period is satisfyingly rich and saturated. As digital photography took over in the 2000s, the transition of print quality noticeably flattens to the all too familiar sheen of Officeworks inkjet production. Although the colour of the prints isn't as rich, the images are just as arresting as Gower's footwear. In the 80s, Gower repeatedly wears a pair of black leather ankle boots with matching red socks. The 90s era is scattered with open-toed sandals, black lace-ups and occasionally gumboots. In the most recent decades, a transition into a well-worn pair of pink thongs, leopard print ballet flats and low-heeled Mary Janes slide Gower's feet into a more comfortable kind of shoe.

But despite Gower's feet, which are undoubtedly the star of the show, it's the places her feet edge their way into that become just as noteworthy as the shoegazing itself. The cut tiled floors in Assisi, a sewer grate design in Soho and intricate tessellated surfaces in Rome's churches all point to the very formations and patterns seen in the collected paper remnants of the 2019 collages back down the road. The series acts as an artwork, a reference point and an archive as we observe Gower discover these reoccurring patterns as influences again and again.

In some instances, these photographs are incredibly revealing of Gower's personal life. An early print in the series that is labelled “Labour Ward, Calvary Hospital, Hobart, 1986” shows Gower's warm looking feet propped up in a hospital bed alluding to a scene before the birth of her son, Ivan. He emerges in a photograph later on in the series gleefully lying on a pink blanket accompanied by an inviting colourful plush soccer ball. We are privileged to see him grow along with his sister, Hannah who was born a few years later, traversing the same pink blanket as a baby seen in a photograph further along the row. As they learn to stand and become taller, their faces leave the image's frame and their feet remain planted next to Gower's and, unsurprisingly, bear a striking resemblance.

There is only one other photograph in the series where Gower is situated in a hospital bed: a slightly overexposed print, labelled “Waiting for an X-Ray, St Vincent's Hospital 2018”, shows Gower's legs resting on a pale blue mattress. The sunlight beaming through the window outlines her glossy red-painted toenails poking out the end of a pale pink blanket covering her legs. Unlike the rest of the series, the cold, bluish tonal saturation of the print –perhaps a symptom of the clinical overhead lighting – stands out as it casts an eerie sheen on the image accentuated by the reflection of the camera flash on the bed frame. The print's label is also somewhat unsettling, leaving the onus on the viewer to decipher exactly what x-ray Gower was waiting for in hospital. However, this question quickly seems beside the point as the series continues; Gower and her feet shift out of the hospital bed and step onto other locations.

This move out of hospital was not experienced by another artist, Carol Jerrems, who also emerged in the Melbourne art scene, and even attended the same college as Gower—Prahran Technical College—in the early 1970s.Yesterday, Carol Jerrems died forty-years ago. Like Gower, Jerrems also photographed herself in hospital. After she was admitted, she kept a photo-diary of her prolonged stay in Royal Hobart Hospital, documenting her own bed and a collection of belongings littered beside it; she took a number of self-portraits of herself pre and post her invasive operations, as well as captured the movement of the various nurses and doctors. They were trying to decipher the cause of Jerrems' rare illness, which eventually led to her dying in hospital. Gower's work goes on. But this strange association with Jerrems only highlights that, like all, this series too will eventually have an endpoint—Gower's eyes that capture her feet in the photographs will close, and her feet will no longer press against the ground we are shown she has spent a lifetime walking over.

Chelsea is a curator and writer based in Melbourne.