Archie Moore, Dwelling (Victorian Issue)

Elijah Money

I am a Wiradjuri guest on the unceded sovereign lands of the Wurundjeri peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nations. This is where I live, work, and am writing from today. I am paying my respects to Elders both past and present. Wurundjeri mob and their forebears have been custodians of this land for millennia. I stand on the land which Aboriginal peoples have performed age-old ceremonies of celebration, initiation and renewal. I acknowledge the living culture and the unique roles in the life of the region. I recognise and respect this cultural heritage, the beliefs and relationship with the land; these continue to be central to the Kulin peoples of both past and today.

Upon entering Gertrude Contemporary, it appears as though the gallery in its entirety has been dedicated to Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist Archie Moore’s solo exhibition, Dwelling (Victorian Issue) (2022). The interior architecture of Gertrude Contemporary, its scuffed floor, exposed skylight, and visible beams, feel like essential aspects of the show. This is in fact the fourth iteration of Dwelling, Moore’s site-specific installation, which has been shown previously at other galleries around the country.

The exhibition is made up of a series of rooms that have been recreated, reinterpreted and reinstated in homage of Moore’s teenhood home. Transported through time, the rooms are riddled with readily identifiable iconography, technology and furniture from the period of the 1980’s in so-called “Australia”. The contents of the exhibition look to be used—hosting stains, chipped paint and pen marks—which all contribute to a feeling of familiarity, of experiences, of memories, a feeling of a home. Most of the furniture was sourced locally, found either in hard rubbish, the tip or at op shops. While the furnishings are a major aspect of the show, the heart of Dwelling appears through the extensive assortment of stickers, trinkets, business cards, bank cheques and other documents. Immense attention has been dedicated to the arrangement of these personal mementos that you might otherwise gloss over in overlooking the decades of devotion required to collect these seemingly insignificant items and to hold them in the memory over decades.

Although the audience is encouraged to physically immerse themselves in this “home”, it’s hard not to feel as though you’re encroaching—fishing for secrets by sneaking in and rifling around someone else’s personal documents, drawers, cupboards and photos. Entering this domestic scene through a weathered white door, the space immediately envelops you through its dim lighting, dark green walls, the sound of ABC humming from a small radio placed on a bookcase and a soft muskiness emanating from the tidily made single bed that is covered with a soft mosquito netting. It’s Moore’s younger brother’s room. Resting on a bedside table is a small chest that when opened reveals the uniform that Moore’s father wore while partaking in an organised cult. An image of a white Jesus hangs on the wall, watching over the room while facing a plastic dollar sign that’s stuck to the back of the door, glistening. On the other side of the room is another door that is left ajar, inviting you to pass through. In closer proximity to the door, it becomes clear that the sticker reads: “Neighbourhood Watch.” This room is an introduction to some of the paradoxes, dark humour and overall vulnerability that is unmistakably present in each of the rooms constructed by Moore.

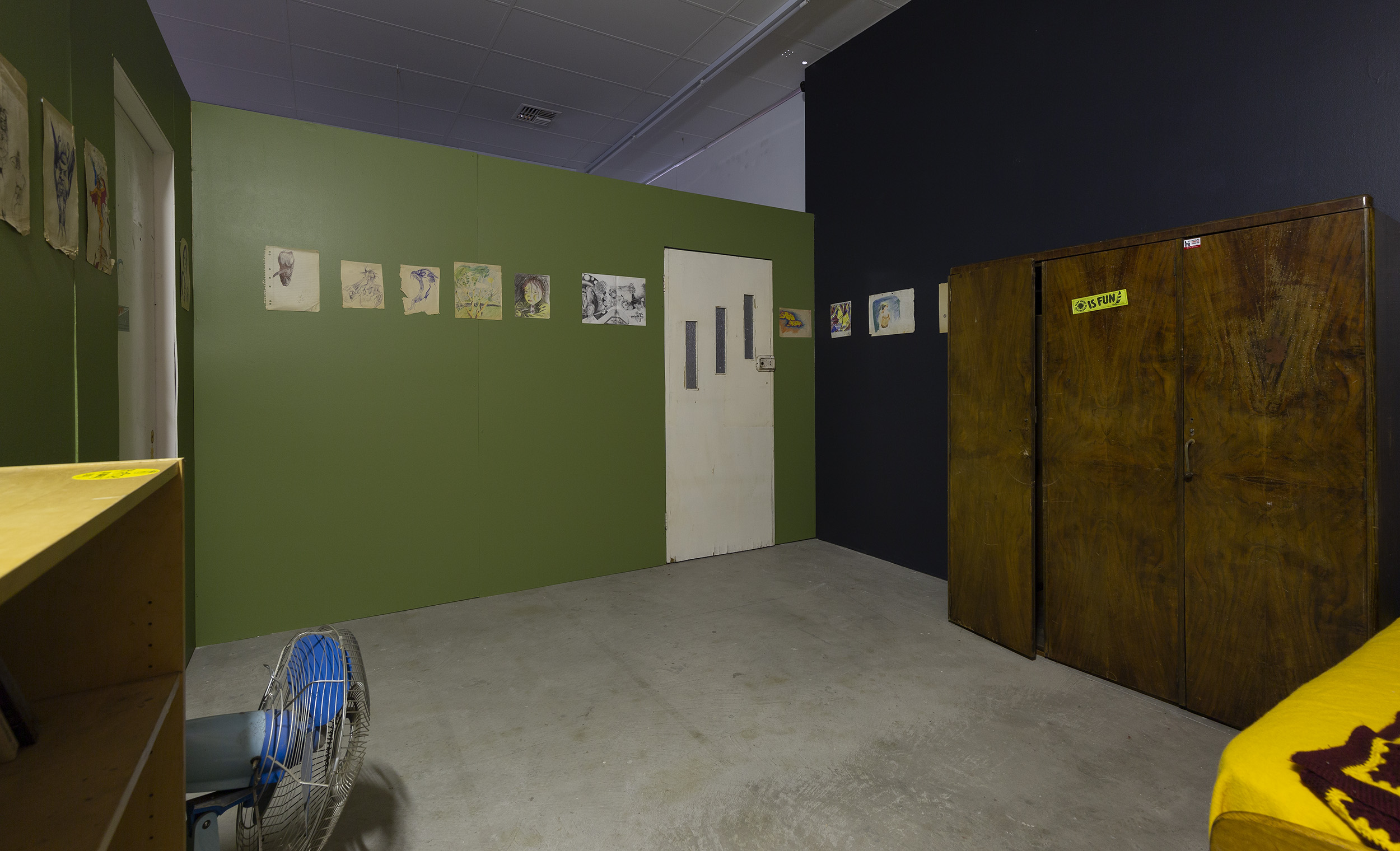

Reclaiming through remembrance, Moore openhandedly shares intimate aspects of his past with each attendee while presenting the rooms, at first glance, as typical of homes of this era. A second room is a spatial enactment of the past bedroom of Archie’s youth. The artist’s childhood sketches adorn the walls. An art accolade reading “highly commended, grade 5 Art” is linked to an old painting depicting a scene from Doctor Who, “dalek” and all. Nearby a letter is Blu Tacked to the wall congratulating Archie for his lottery winnings with a bank cheque attached for the total sum of $1.20. This is on display above a partially filled bookcase, while an electric fan and dart board rest on either side. Opposite, sits a dark wooden closet, which has a poem on the subject of “semen” attached to the side. Opening the doors of the closet reveal a horny pen drawing stuck to the inside, while a shirt ladened with skulls hangs next to an old school uniform. It’s showcasing a teenage boy’s room that is both amusing and believable. Like many facets to the show, there are numerous hidden elements within the closet that could easily be missed. One of the drawers hold a series of documents and papers ranging from infringements with the law, to school reports and of course, more drawings. Prompting the viewer to participate in the show as if investigating Moore’s life, it can be interpreted as encouraging settler colonial Australia to look deeper than surface level into Indigenous history, politics, culture and social life, which is lived both collectively and personally.

Next, you’re met with a living room and a television playing classic 80’s programs to sit and enjoy on a vinyl couch. The vinyl styled couch is spacious and reminds me of hot summers as a child and having to sweatily peel myself off, mindful not to touch other parts of the vinyl seats that had been baking in the heat ready to sting my flesh. Another vinyl chair sits in the corner, which is marked by a few biro pen drawings of a satanic nature, taunting that it has been directly plucked from a different memory, a memory that again infuses my own, this time those of the many bong sheds from my teen years. It’s these kinds of memories that are evoked when experiencing Dwelling. Although, this is not solely my story being told, it is one that holds varying forms of resemblance to many.

Walking through feels comfortable, like you’re visiting a relative while simultaneously apprehensive to disrupt these physically embodied recollections. Pulling back the plastic fringing hanging in a door frame unveils the kitchen. The walls are partially scorched and paired with a soundscape of hard breathing, while a dining table sits in the middle of the room. Some of the burn marks form the words of places where Moore’s father had lived and worked over the years. After one of the previous iterations of Dwelling was exhibited, a member of the public reached out to Moore as they had some insight on tracing his father’s footsteps. Since obtaining that information, the names of these places were included as part of this ‘Victorian Issue’ of the show. On the dining table are a few tin boxes, his father’s business card and a small, black, laughing doll with a crown of dark, reddish-brown hair surrounded by scattered clippings of the same hair. The use of eclectic decorations is a double-edged blade in that they continue to share Moore’s humour, personality and sense of style, while reminding us of some of the compromised conditions that he, like many others, were raised in.

Dwelling confronts intergenerational trauma and violence from a relatable lens that traverses through time and is transgenerational without falling into the trope of “trauma-porn”. Hearing the dripping of a tap lures you into the bathroom: a dark long room with a toilet, facing a basin, in front of a clear vinyl curtain where a bathtub sits. It is perhaps the most ominous of the rooms and a standout in terms of the symbolism that it contains. Covering the walls is a reptilian-styled wallpaper referencing Moore’s mother’s fear of having her children taken away from her if they weren’t “properly” groomed, ensuring their skin didn’t look “scaley”. This is accompanied by the strong and distinguishable scent of Dettol specific to this room. Discreetly placed in the wall overlooking the bath is a small camera lens, an ever-present reminder that Indigenous peoples are under constant state surveillance and privacy is privilege that is not afforded to many of us. Atop the sink is a collection of medicinal goods for treating earaches/wax, tinea cream as well as nose spray and dental floss. I can’t help but immediately consider these specific items were chosen to highlight the racialised, preventable illnesses and diseases that many mob continue to be plagued with today. A single example is major hearing loss due to otitis media disease, which continues to affect a shockingly large amount of community, disproportionate to the broader population. Indigenous health and wellbeing is consistently swept under the rug by gubbament with little to no improvement (and in some instances deterioration) seen over decades. Immersed in the sterile scent mirroring that of a hospital is the sore reminder that despite the amount of time that may have passed, the longevity of our bodies is not a priority of the gubbament.

Finally, in the last room there is something of a classroom. Rows of chairs clutching the remnants of spider webs are set up facing a projected documentary on the mining industry, while a small basic shack, styling together pieces of corrugated iron with a dirt floor, is located in the right-hand corner of the room. The shed is a homage to Moore’s grandmother’s home; he states that “hers was much nicer.” Above the structure, a panel has been removed from the gallery ceiling to create a skylight and share some of the inner workings of the structure. A soft glow emanates from the room, but the darkness is quite consuming when inside. A wire day bed is assembled towards the back of the shed, a raw depiction of the aesthetic that Ivan Sen uses in such films as Mystery Road (2013) or Goldstone (2016): blak neo-noir. Knowing some of the atrocities that so many mob faced through various forms of educational institutions, the air in the space suddenly feels tense. Without realising it, I found my brow furrowed and my jaw clenched gazing at the large ruler resting in the corner.

Creating a deeply evocative exhibition, Moore demonstrates an abundance of emotive range through Dwelling. Exposing himself in this sincere display of vulnerability, this multi-faceted, large-scale installation is all-consuming. While there is a strong sense of humour running through the show, such as the profusion of drawings and stickers, the duplicity of undeniable truths is salient. Viewing this exhibition has been an absolute highlight of my year and is ultimately unforgettable.

Elijah Money (he/him) is a queer Wiradjuri brotherboy who was raised on Kulin Nations where he continues to reside. His practice includes visual art, written work, installations, performance art and more.