Diane Arbus: American Portraits

Chelsea Hopper

“You can’t take any photos”, I was told at the front desk. The request was unexpected, as restrictions of this kind for an exhibition seemed slightly dated considering how accessible and abundant images have become in our digitally soaked, super-sharing culture – not to mention how widely available many of the images seen in the exhibition are online. Was this just a cautionary move to avoid the typical copyright hole on the grounds of image reproduction rights? It seemed a little heavy handed, as the same logic applied to the marketing of the exhibition. In the foyer, for example, there is no promotional image, only the title displayed in bold, white lettering. There lies a sweet irony in this as the exhibition stages some of the most iconic images in the history of twentieth century photography.

The photographer responsible is Diane Arbus. At Heide Museum, a touring exhibition organised by the National Gallery of Australia, curated by Anne O’Hehir, simply titled Diane Arbus: American Portraits, features 36 photographs taken during her last decade of life, between 1961 and 1971. This collection, acquired in the lead up to the opening of the NGA in 1982, is one of the largest public holdings of prints made by Arbus herself outside New York. Although billed as a solo exhibition, eight other American photographers sit amongst the rare vintage Arbus prints. A curatorial manoeuvre I would argue that highlights just how distinctive and unique Arbus is as a photographer for both her style and subject matter. Yet the inclusion of work by iconic photographers Walker Evans, Weegee and Lisette Model, by Arbus’ contemporaries William Klein, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Milton Rogovin, as well as pictures by the slightly younger William Eggleston and Mary Ellen Mark also permits the opportunity to see the ways in which they each used the camera to reflect upon and transform the world around them during the American post-war era.

With the presence of these additional photographers, it is hard to resist darting back and forth in the gallery to make comparisons. In relation to Arbus, an easy connection can be made by ruminating in the room entirely devoted to Lisette Model. Model, who taught Arbus in 1958, was drawn to the same or at least very similar subject matter in her portraiture. Among a swath of portraits of exuberant characters found on the streets and public spaces of New York, a stand out is a very large woman in a black bathing suit, with hands on knees, smiling in the Coney Island tides. In a vitrine nearby sits Model’s first monograph, opened to the centre spread, where the very same bather appears lying in the waves exuding an inordinate amount of joyfulness and confidence. Here lies (quite literally) Model’s skill in capturing a revealing moment when an ordinary person doing a common activity appears strange. Although Model firmly denied exerting any direct artistic influence on Arbus, a push for her to seek out subject matter (namely, the flawed and different) was a turning point for Arbus in constructing her independent style.

This style is cemented in Arbus’ most famous photographs, represented here by seven large black-and-white prints defiantly hung in a row. The thrill I get from these is seeing the gap between the idea that the sitter or the subject of the photograph has of themselves, and what one sees. I will never know exactly the facts of the sitter’s relationship to Arbus—a complex, morally layered one between humanised and dehumanised, exploited or empowered. Though one can assume that to get this close to her subjects, Arbus often knew and befriended them. The giant, Eddie Carmel, in Jewish Giant at home with his parents, in the Bronx, N.Y.C. 1970, whom Arbus met a decade before this photograph was taken, is one of many such relationships she maintained throughout her life. Like many of her photographs, they are very carefully chosen from a series in which the dramatic moment of visual and apparent emotional tension between Carmel and his parents is very different from what you see in the rest of the photographs that Arbus took during the session. These tensions are abundant, from the décor, the gesture of the father, with his hand hesitantly sliding into his pocket, but more obviously, how Carmel is so ambiguously posed in a manner implying he could crush his parents or embrace them. Arbus’ fascination with issues of sameness and difference (clearly stated in her most famous image, Identical twins, Roselle, N.J. 1966), home and homelessness, self-acceptance and cover-up, freakish and normal, and the insides and outsides of the mainstream, can be seen here in the relationship between Eddie and his parents.

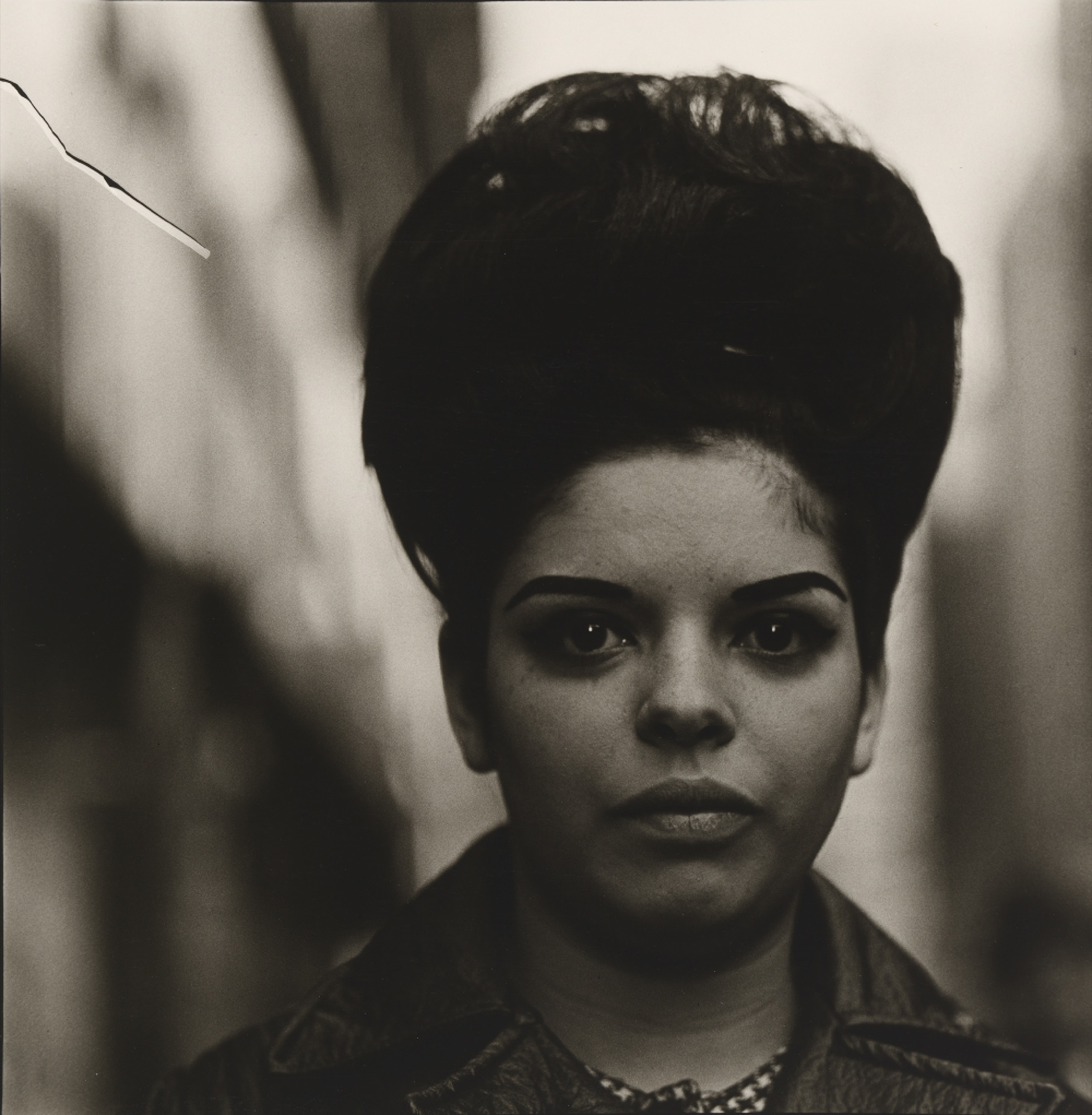

The earlier photographs by Arbus captured in Central Park and Washington Square uncover another place where her subject’s identity is both performed and practised. These rich and unpredictable encounters were the result of a single chance meeting between Arbus and her subjects, whether children, youths, misfits, young couples or well-dressed strangers. What drew Arbus to the park – and in this she seems to follow Model – is its innate ability to break down class concerns and self-consciousness. Woman with a beehive hairdo 1965 is so telling of this, a woman who holds a gaze as deep and intense as her painstakingly groomed hair style.

Flanked in one of the wings of the exhibition are the works of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, who both exhibited alongside Arbus in her first major exhibition, New Documents held at MoMA in New York in 1967. Collectively, the works of (then) young, relatively unknown photographers presented a significant break from their predecessors of the 1930s and 1940s, marking a shift away from a recognisable documentary style towards one in which the subject is more elusive, reflecting a society that had itself become more fragmented and complex. As MoMA curator John Szarkowski wrote then in one of his extensive exhibition labels, ‘they redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it.’ However, beyond this (possibly now lost) historical connection (and without supportive wall text), it is difficult to see why their inclusion in the current exhibition was considered necessary, as what sits within the frames of Winogrand and Friedlander’s images is vastly different from that of Arbus. The same might be said for the inclusion of William Eggleston. His rich, deeply saturated colour photographs of mundane suburban life appear extremely different in tone and intention to the rest of the exhibition’s modest black-and-white prints. But Eggleston’s skill, much like Arbus, is in his compositions, which makes the ordinary strange. Perhaps one of the exhibition’s strengths is that it makes apparent how Arbus influenced, but was also part of, an effort to reframe American portraiture, even if the specific historical context that informed this shift is no longer necessarily apparent to us.

O’Hehir’s knack for selection and her ability to draw from the NGA’s extensive collection of photography to contextualise Arbus demonstrates exactly how she was such an innovative photographer in forming a new kind of photographic portraiture. By sitting her amongst her contemporaries, it becomes clear that she was not alone in documenting the social landscape of America.

It’s unfortunate to both encounter these types of restrictions on photographing the works in the exhibition as well as an absence of images in the marketing and promotional material, as this undeniably comes at a cost to the legacy of Arbus. The culprit is not the curator, the exhibition or the museum but, it seems, the Arbus estate itself, which seeks to privilege biographical readings of her work over any contextual analysis. By so rigorously limiting and controlling their circulation and reproduction, the estate has in a way assisted in stripping away the modernity that was once such a crucial aspect of the pictures. The specifics of Arbus’ radicalness – if indeed she ever was radical – has become difficult to read.

Chelsea Hopper is a curator and writer based in Melbourne.

Title image: Installation view, Diane Arbus: American Portraits, Heide Museum of Modern Art, photograph: Christian Capurro)