Design for Life: Grant and Mary Featherston

Jane Eckett

Exhibitions of modern Australian furniture and design are enjoying a resurgence in recent years. There was the NGV's Mid-Century Modern: Australian Furniture Design in 2014, and Take a Seat: Australian Modernist Seating at the Penrith Regional Gallery in the same year, followed by a focus on overlooked émigré designers in The Moderns: European designers in Sydney, at the Museum of Sydney in 2017, and an exhibition of Meadmore furniture opens shortly at the Ian Potter Museum of Art. Permanent hangs of Australian collections in state galleries invariably incorporate at very least a Schulim Krimper sideboard or Fred Ward desk. Modern design is to the fore of contemporary taste, as reflected not only in the pages of glossy architecture magazines but also in the crop of mid-century modern furniture stores mushrooming across the country and in the production of high-end replicas of iconic works – including a range of Featherston chairs launched spectacularly at ACCA in 2016. Heide's present survey show, Design for Life: Grant and Mary Featherston, is therefore clearly of the moment.

The exhibition brings together a formidable team, led by co-curators Kirsty Grant, whose former projects include Mid-Century Modern, and art historian Denise Whitehouse, who has worked closely with Mary Featherston on the Featherston archive over the past fourteen years. Mary Featherston has guided aspects of the exhibition display, notably the “nature wall”, while her daughter-in-law, designer Vicky Featherston Tu, has overseen the sensitive exhibition layout and developed an interactive 'Featherston Design Studio'; more on both of these shortly. For the most part, items of furniture are presented on modest low white platforms with framed drawings and photographs on the walls behind. Hands-off glass cabinets are kept to a minimum, reserved only for ephemera and small items, such as the glass buttons that were the bread and butter of Grant Featherston's early career. A handful of what might be termed period displays enlivens this simple presentation, bringing together rugs, paintings, coloured walls and period lighting to harmonise with suites of furniture.

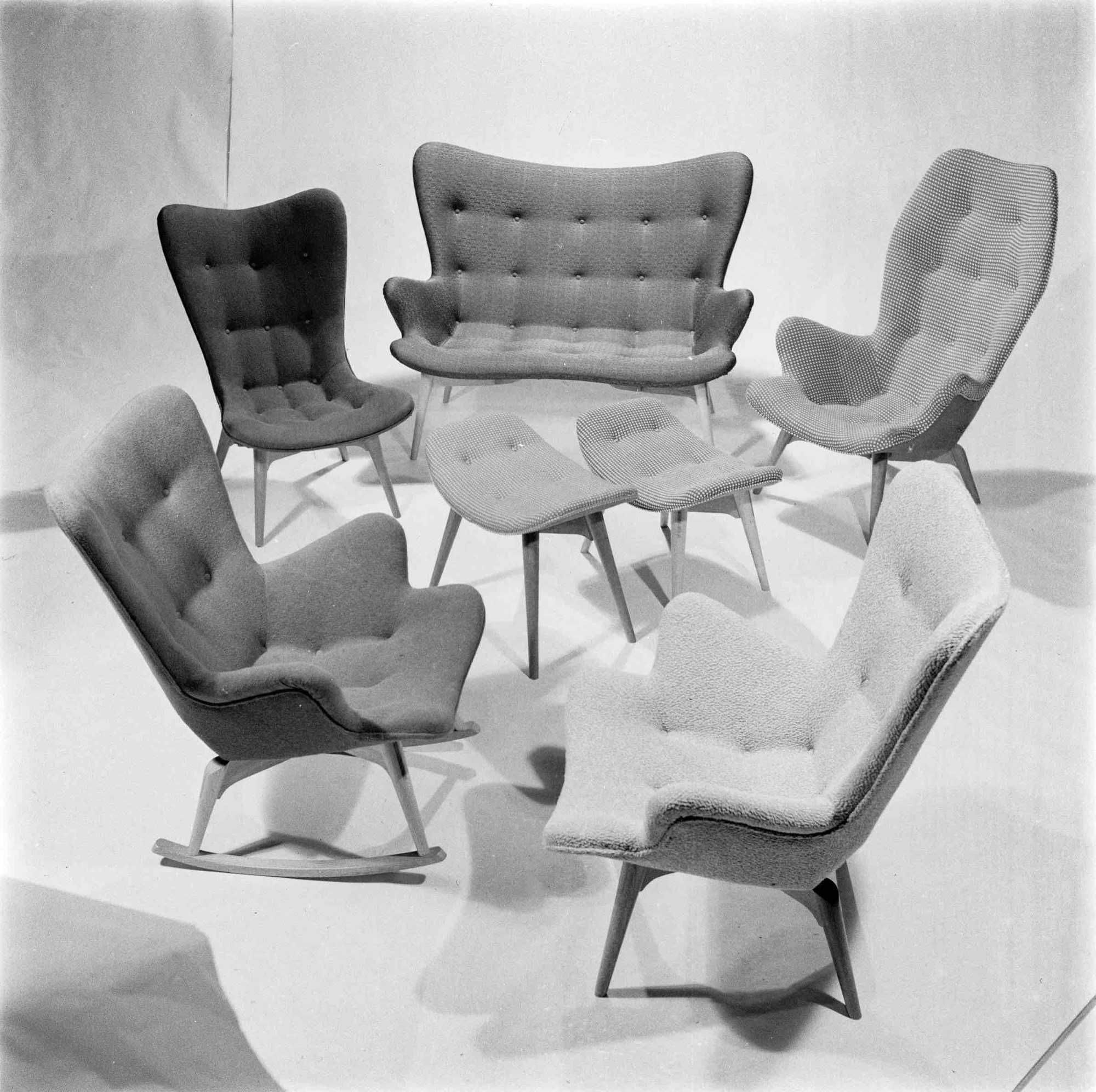

The result is an experience at once heady, stimulating and seductive. We breathe in the aura of “original vintage” furniture, alternately pausing to admire the immaculate upholstery of the R152 Contour Chair, 1950 (which the NGV purchased just four years after production, thereby preserving its mint condition), and lingering over endearing signs of wear and tear in chairs loaned by key collectors such as Conor Lyon. The relationship between the works exhibited and the bodies they are designed to support is palpable. Featherston chairs have proved so enduringly popular, one suspects, because they were designed with comfort and economy in mind – “design for life”, as the design duo consistently emphasised throughout their practice.

In the small project gallery, adjacent to the foyer of Heide III, a display of the Featherstons' workshop tools instantly immerses us in the quotidian reality of their design practice: mechanical pencil and compass sets; wooden rulers, drafting brush and T-square; an artful arrangement of clear plastic protractors, set squares and French curves; wooden-handled chisels, dressmaker's scissors, a Stanley knife, needle-nosed pliers, forceps, wood samples and other arcane instruments the name of which I am ignorant. There is a simple but deep pleasure to be had in studying these trade tools, identifying them and registering the mathematical precision and handmade origins of what were, after all, mass-produced products. They are displayed along the uppermost of four open white shelves, below which are propped unframed photographs of different Featherston chairs in the process of production, from the earliest pencil sketches and cardboard prototypes to component parts of moulded plywood and plastic formwork, factory assembly shots, technical testing of the Talking Chair, for Expo '67, and publicity stills of the final products. The open-shelved display of these tools and photographs communicates honesty (of both work practices and exhibition design) and unmediated access to the Featherstons' world. In the same room we find the 'Featherston Design Studio', where visitors are invited to design their own chair prototypes by experimentally folding and stapling small pieces of pre-cut card and hanging them on wires against the opposite wall – creating a visually arresting display that at once underscores the experimental nature of product design and points to the continued relevancy of Featherston designs to our current times.

In the long central gallery a further set of shelves dubbed the “nature wall” presents a selection of natural objects from the Featherstons' collection that have inspired their design practice, interspersed with more photographs. This is a more unruly, erratic and yet poetic arrangement than the workshop display. The natural objects encompass a diverse range of forms: bones, nautilus shells, seed pods, curved gum leaves, feathers (but no stones), a densely woven bird's nest, a bird's wing, fragments of bark, a cross-section of a tree trunk, and a lichen-encrusted branch. Significantly, the photographs are this time interspersed with the objects, underscoring the relevance of the objects to images, while the photographs depict the Featherstons' interior design and environmental design projects rather than industrial design products. Notable among the former are the Featherstons' own Robin Boyd designed home on the Boulevard at Ivanhoe, with its seamless integration of indoors and outdoors via the central garden and a large south-facing window looking onto the surrounding native vegetation, and their work for Roy Grounds on the NGV interior fit-out in 1966-68. The environmental designs are school interiors developed from Mary Featherston's pioneering work on child-centred learning environments, which we hear further about in her own words through the documentary film that screens adjacent to the nature wall.

The emphasis here on drawing inspiration from nature brings to mind Henry Moore's collection of shells, driftwood, pebbles and bones that he displayed around his home and studios at Much Hadham, and his much-quoted writings on the importance of these objects to his thought process. Perhaps it is no coincidence that, on the other side of this central gallery, a single sculpture by Grant Featherstone, Head Study No. 1, c. 1950, evidently responds to Moore's Helmet Head series, begun in 1939 and returned to in 1950. Both evoke weathered bones and play with a motif of rounded protective forms enclosing brittle inner forms. This single sculpture of Grant Featherston's and a pair of trace monotypes by him also underscore his engagement with design beyond industry, blurring artificial demarcations between artist and designer.

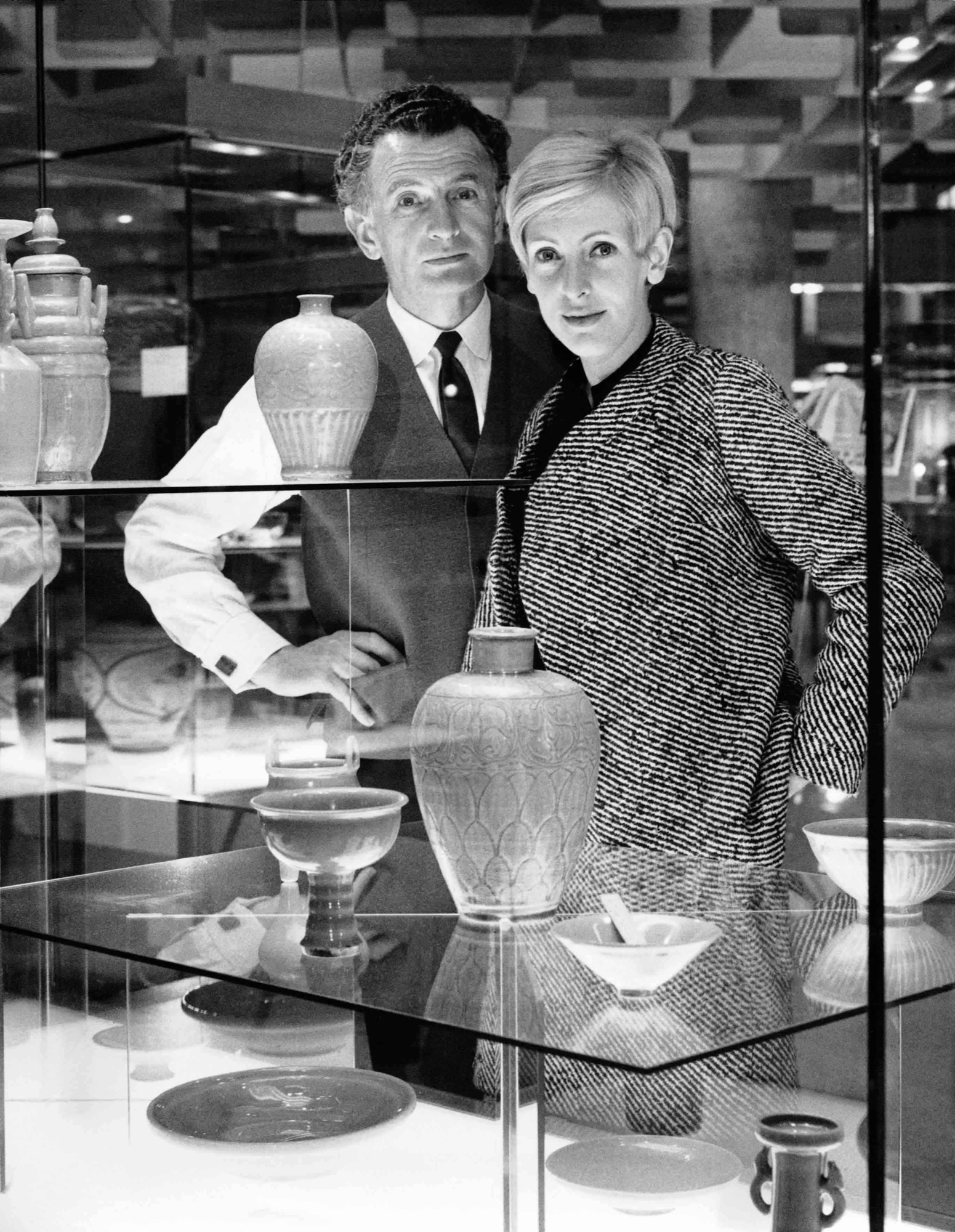

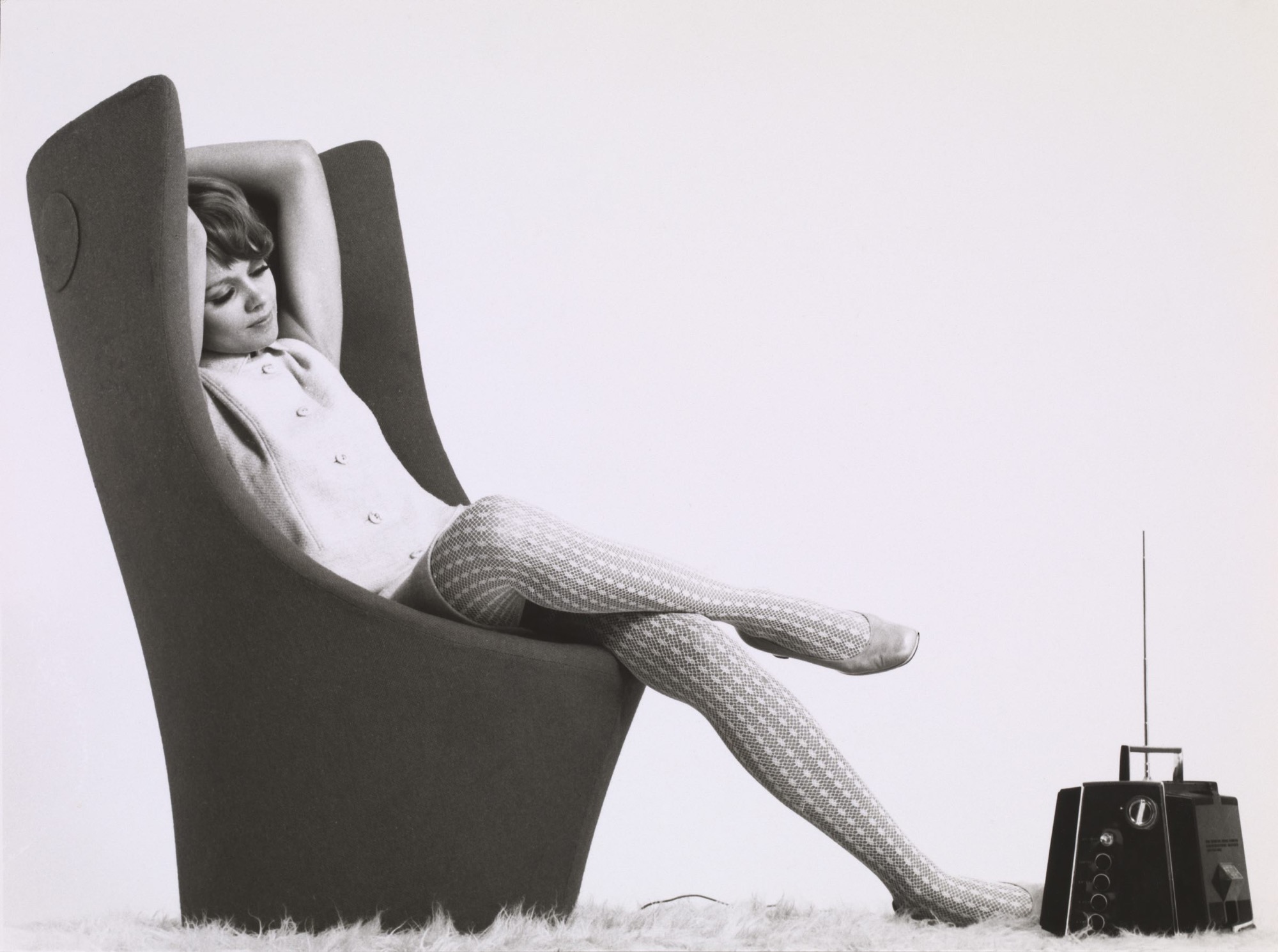

Given the exhibition's title, I had expected a “duographic” rather than monographic approach. However, from the first central gallery it becomes clear that the exhibition focuses on Grant Featherston, whose career really took off in 1949 with the complete suite of furniture he made for Robin Boyd's House of Tomorrow – the central exhibit of the post-war Modern Home Exhibition. Featherston became something of a household name in the 1950s with a string of successful designs: beginning with the Relaxation Chair, then the Contour Chair, the Curl Up Chair and so on. By comparison we learn nothing of Mary Featherston's work prior to her marriage to Grant and the establishment of their joint design firm. This is presumably because she was still completing her diploma in interior design at RMIT when the pair met, but it does convey a sense of Mary playing second fiddle to Grant. There are echoes here of Charles and Ray Eames; until the publication of Pat Kirkham's critical monograph in 1995, Ray Eames was all too frequently elided from discussions of the Eames' design practice. The impression is compounded by the highly gendered advertising material that was used to promote these designs; photographs of young female models indulgently reclined or curled up in Featherston chairs seem to reinforce the unspoken rhetoric that these were designed by men for women. A single enlarged Mark Strizic portrait photograph of the Featherstons standing behind the glass vitrines they designed for the NGV's Asian collections silently attests to their joint creative effort, but Mary Featherston's exact contribution to their joint projects is unclear. Her presence is implied in a number of ephemeral items, including some seen previously in the Emily Floyd exhibitions at the NGV and Heide in 2014 (Floyd's mother and Mary Featherston were both members of the Melbourne Community Childcare Movement in the late seventies and early eighties; Mary's striking graphic design for the group's newspaper, Ripple, inspired a series of Floyd's prints and the pair have also collaborated on some cross-generational projects). But her extensive research and work in the area of child-centred learning environments is represented only through a small selection of photographs incorporated into the nature wall and her oral testimony in the documentary film.

This odd ghosting effect, whereby Mary fades somewhat from view, is perhaps the result of what seems to be a conscious decision to exclude biographic information from the exhibition. Visitors wanting to learn anything of the Featherstons' lives beyond their mature work must instead turn to the richly researched catalogue that accompanies the exhibition. It is there that we discover that Mary was in fact Grant's second wife; his first wife, Claire Skinner, was an artist and textile designer, trained, like Mary, at RMIT, who ran the glass button factory for Featherston while he embarked on his range of furniture designs. Claire's name appears in one of the magazine articles included in the exhibition's displays of ephemera, from which we learn that she evidently worked with Grant in some joint capacity, but there is no other mention of her – another Featherston ghost we surmise. The catalogue also supplies useful biographic information on both Grant and Mary Featherston, probing Grant's family background in an attempt to answer why, in late 1938, he embarked on a career in design, quickly branching out on his own in the fledgling field of industrial design, and contrasting his Geelong origins with Mary's English upbringing and her family's migration to Melbourne. Here, if not in the exhibition, we encounter the classic “duographic” approach.

Contextual discussion of other designers, both those working in Australia and overseas, is minimal in both the exhibition and catalogue. The familiar names of Meadmore, Snelling, Ward and so on appear in some of the magazine articles in the display cases, but are not mentioned in the wall texts. In the catalogue Whitehead takes pains to emphasise Grant Featherston's originality. Where he is seen to be taking inspiration from overseas designers, we are told he does so “with experimentation in mind”. By way of contrast, Gordon Snelling's webbed chair is described merely as “a copy of Jens Risom's 1941-42 chair design”. Davina Jackson, in her recent monograph (Douglas Snelling: Pan-Pacific Modern Design and Architecture, Ashgate Press, 2016), gives a more complex genealogy for the Snelling chair line, but concludes that both the Snelling chair and Featherston's webbed Relaxation Chair range were ultimately copies of Risom's designs for Knoll, adding that Featherston also closely studied Bruno Mathsson and Alvar Aalto's 1930s' originals. All of this leaves the non-specialist with the lingering question: to what extent was mid-century Australian modern furniture derivative of overseas models?

An hour or so after visiting the exhibition I happened to call into a café local to home and there, by odd chance, found myself looking at a crumpled up postcard advertising the Heide exhibition on the table before me. The tag line intrigued me: “Design that survived the 60s”. Did it? The photograph on the postcard was not one I recognised from the show (perhaps I missed it in one of the vitrines of ephemera). It depicted a Contour Chair set before a wall papered with pink and olive green flowers, a crazy paved stone faced fireplace, a glimpse of an orange floral print hanging over the fireplace, a glass coffee table with red studio glass ashtray and – that icon of sixties kitsch – a sunburst clock. This was a far cry from the elegant exhibition I had just left. Admittedly, one or two works in the exhibition seemed heavily bound to the period in which they were made. The khaki toned fabric with “Aboriginal style” turtle motifs used to upholster the NGV's Cone Dining Suite could only have been made guilt-free in the fifties, while the plastic Stem Dining Suite, with its light-hearted allusions to daisies, seemed perfectly fitted to the space age in which it was made. Interestingly, early photographs of the Featherstons' own home feature the Stem Dining Suite, while more recent shots reveal the chairs have been replaced by those classics of early modernist design: cane-backed bentwood chairs. Wood and natural cane replace gleaming white plastic: was this change predicated on taste or need? The Stem Dining Suite must have been eminently practical when the couple had young children in the way that cane-upholstered chairs are not. But plastic furniture has not yet quite come of age in the way that Featherston's upholstered plywood chairs have. Perhaps in another ten years we will see a rash of exhibitions focussing on plastic furniture. Time will tell.

Jane Eckett is a sessional coordinator in the art history and gender studies programs at Melbourne University.

Title image: Featherston House, Ivanhoe c. 1972. Photographer: Mark Stizic © Estate of Mark Strizic.)