David Hockney: Current

Francis Plagne

With David Hockney: Current, the NGV has made the unusual decision to devote a major exhibition to a selection of work from the last decade by a 79 year-old artist active since the early 1960s. Perhaps this can be explained by the popular appeal of the iPhone and iPad drawings that make up much of David Hockney's output in this period, but the choice is interesting insofar as the narrow focus directs our attention to a body of work that would undoubtedly appear as a mere afterthought if seen in a retrospective exhibition that also included Hockney's best paintings of the 1960s and 1970s.

The exhibition invites speculation as to whether—to use the phrase coined by Theodor Adorno in his analysis of the late works of Beethoven and expanded by Edward Said into an interpretative model—Hockney has developed a 'late style'. Although Hockney's recent work demonstrates none of the tragic intransigence that, in Adorno and Said, makes late style a paradigm of aesthetic resistance, neither does the work on display here sagely 'crown a lifetime of achievement'. Instead, like the late works of Picasso, Hockney's late work is a mess, a jumble of experimentation, ossification, and narcissism.

Hockney's introduction of the iPhone into his practice in 2009 is the main justification for showing his work of the last decade in isolation; and these works, alongside a later series of iPad drawings, are probably the most interesting in the show. The exhibition opens with a room dedicated to dozens of drawings made using the app Brushes, mainly focused on domestic details (a vase of flowers, the view from a window) and sometimes presented in Impressionist-inspired series of variations on the same subject. Dotted among these are a series of very slight text-based pieces, some of which feature somewhat cringe-worthy phrases extolling the virtues of the iPhone.

The drawings are presented both printed out on paper and displayed on iPhones, sometimes as a simple succession of images and sometimes in the form of animations that document their completion stroke-by-stroke. These animations, which also accompany the much more impressive Yorkshire and Yosemite landscape drawings elsewhere in the show, demonstrates the facility and intuitiveness of Hockney's drawing. But like Clouzot's Le mystère Picasso, the thrill they provide feels somewhat cheap, a repetitive and shallow display of manual skill. The effect of this emphasis of the process over the finished work is unfortunate, making Hockney's use of these digital tools feel less like the next episode in an artistic career characterized by a continuing exploration of unlikely new technologies (Xerox, Polaroid, fax) and more like a friendly grandpa's harmless but slightly annoying new hobby.

From a distance, the large iPad drawings in The arrival of spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven) and Yosemite series (both 2011) can look like paintings, post-Impressionist landscapes built up from layers of strokes varying in thickness and texture, often employing lurid shades of pink and green oddly reminiscent of late de Kooning. In the Woldgate series, the ghost of Cézanne is felt particularly strongly in a recurring central path that ambiguously plunges forward into the depicted scene and rises up the picture plane. The imitation of painterly effects in these digital drawings is quite impressive, and a couple of the sparer images in the Yosemite series manage to capture something of the grandeur of the scene in a way that might not have been expected from the medium. But these large landscape works are at their best when Hockney is less traditionally painterly and embraces the possibilities of his app to create spray-painted and airbrushed effects that give the drawings an airy, weightless appearance.

(Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010), 2010–2011, 36 digital videos synchronised and presented on 36 55-inch screens to comprise a single artwork, silent, 4 mins 18 secs. Collection of the artist © David Hockney

The contradiction between Hockney's medium and the tradition of painting to which he refers creates the interest in these works. At least since Courbet, and in a way that Impressionism and some later Cézannes were radically to intensify, the painterly landscape achieves much of its poetic frisson from the tension between the material density of the painted surface and its representational function (just as modern poetry will often obsessively mull over the pull between the word as sound or written mark and immaterial sense); in this way, some of Courbet's seascapes, for example, manage to capture something of the intensity of the experience of nature precisely insofar as they do not represent it. Hockney's 'painterly' landscapes are formally similar to this tradition, but looking at these drawings close up (each one made up of four large sheets of paper) one is struck most of all by their immateriality, by how the marks that make up the image float on a surface that offers no resistance. They shimmer in the eye, an image without body, exactly, in this regard, like the image on a computer monitor or smart-phone screen. Digital images have, of course, a physical basis; but the effect of weightlessness they create is undeniable when compared to an image inscribed on a traditional support. The strength of these works is to illuminate and prompt an experience—in a way that digital video possibly cannot—of the distance that separates the tradition of painting to which they refer from the digital medium through which they have been achieved. The tension between the material and the optical, central to Greenberg and Fried's analysis of Pollock, for instance, has been left behind here; and in articulating this immaterial opticality, these works outline something obvious but not always conscious about our contemporary relation to images.

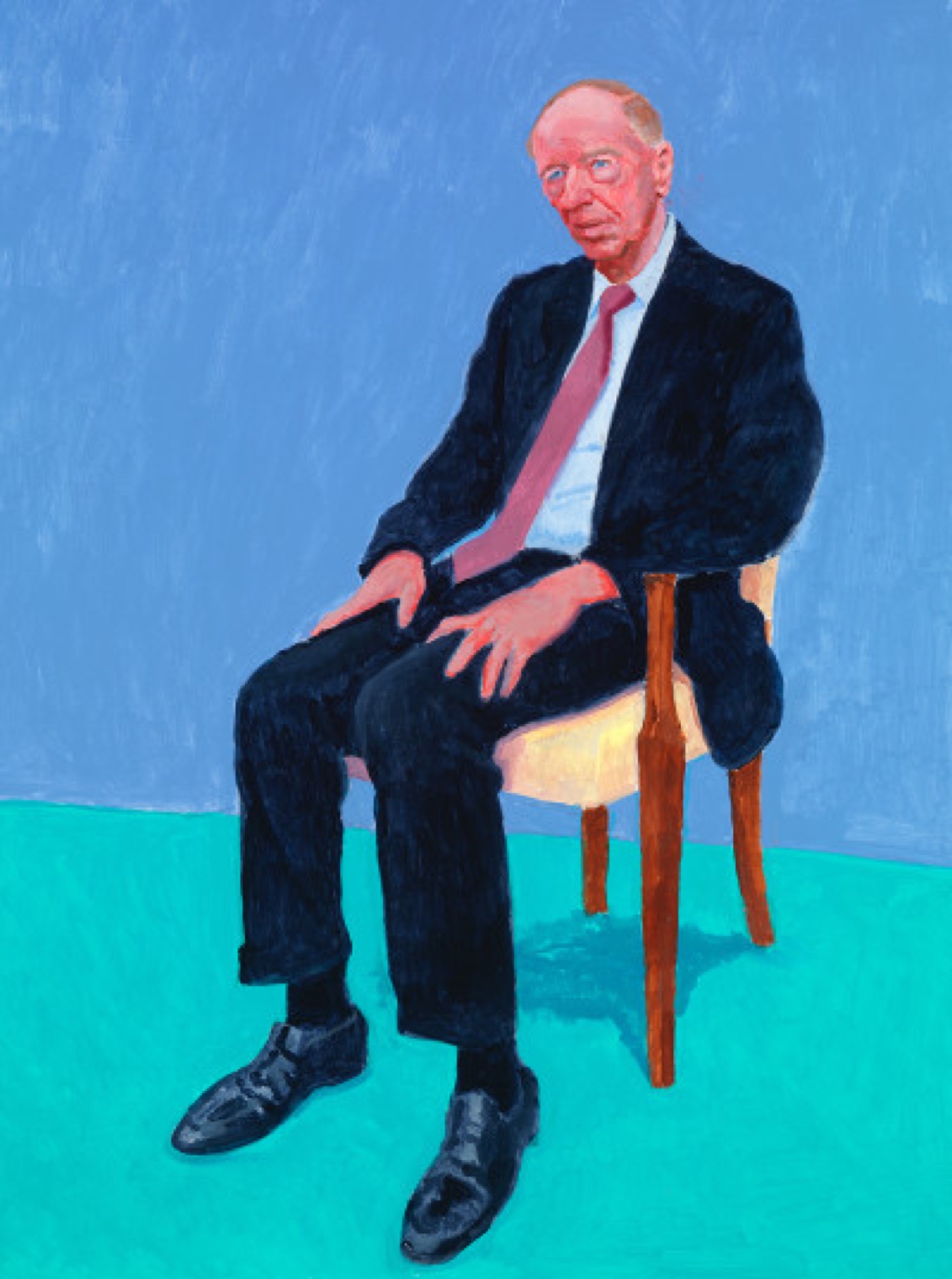

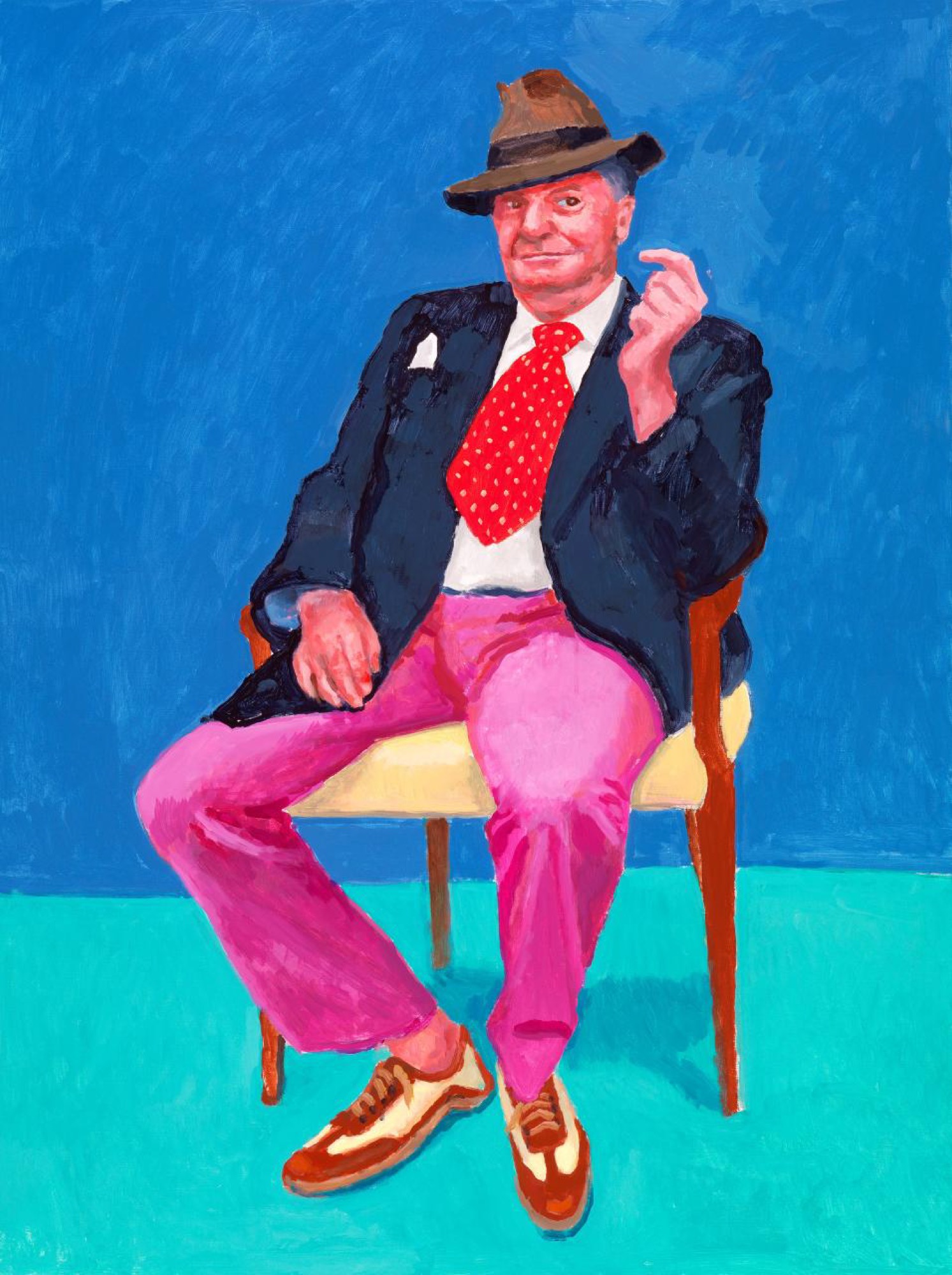

The enormous series of 82 portraits & 1 still life (2013–2016) is underwhelming. The 82 portraits represent a seated succession of the artist's friends and colleagues against variations of the same blue and green background. Some of the individual portraits stand out—Lord Jacob Rothschild, for instance, with his expertly rendered slouch—and there are moments of impressive and economical painting, mainly in the sitter's clothes, which often create a pleasing and Manet-esque half-illusion of solidity with a few simple strokes of contrasting light and dark. However, the overall effect of this gallery of bankers, collectors, curators, and celebrities is depressing, leaden with the peculiar lifelessness of official portraiture and a deep sense of irrelevance. (The glumness of this room is particularly marked because a couple of paintings shown in another room from the series The Group (2014), especially one which depicts a group of figures in gym gear within a studio space rendered with some of the gentle spatial distortion of his early isometric paintings, still carry something of the charm of Hockney's Californian paintings of the 1970s; a pastel-clad utopia of individualists who cohabit the frame in pleasant anomie.) The enormous size of the series certainly does it no favours, framing this series of tastefully well-dressed art-world functionaries and friends of the rich and famous not as a series of personalities, but as an unintentional collective portrait of an archaic elite.

Similarly, the presentation elsewhere in the exhibition of enormous numbers of drawings on iPhones and iPads in addition to those printed out and displayed on the walls undoubtedly weakens the show. Unlike other artists who rose to prominence in the Pop period, Hockney has never really worked serially. The exhibition here of dozens of similar works is simply intended, as a phrase from the wall text tells us, to 'capture Hockney's unwavering artistic drive'. It certainly does this; but as in the case with the late Picasso, one has the distinct feeling that this comes at the cost of placing adulation for the productive capacity of an obsessive artistic personality over engagement with the works produced.

The final room of the exhibition provides its most memorable experience (except, perhaps, for the unintentional shudder that awaits the viewer when confronted with Hockney's woeful 'photo drawings', the less said about which the better). The video installation The four season, Woldgate Woods (2010–2011), documents seasonal changes in the East Yorkshire landscape in the form of four videos, each made up of nine individual projections made by attaching nine cameras to a car and driving slowly down a country road. These nine component images are presented in a grid that composes a single image, but, as in Hockney's photo works of the 1980s, the composite image is only roughly unified: each camera is set to a different zoom and individual projections sometimes overlap one another or leave a gap.

Hockney (and the NGV) call attention to the influence of Cubism on the work. In one sense, this influence is only evident on the work's fragmented surface, as Hockney doesn't seem particularly interested in the investigation of the means of representation that marks the heroic period of Picasso and Braque's Cubism. (Hockney's landscape is very much seen, not read, to use Kahnweiler's distinction). But the post-Cézanne idea, also present in Cubism, of presenting the experience of a scene as a succession of views on it—thereby leaving behind both spatially and temporally the fixed, single viewpoint of European painting since the Renaissance—is realised by Hockney quite effectively here. The fragmentation of the image into a series of sensual details that still hold together as a scene, combined with the slow movement forward into the landscape, does capture something of the experience of basking in natural beauty—the captivation by momentary appearances that receive their force from the material density of a whole that is never, of course, seen all at once. This, like the East Yorkshire and Yosemite iPad drawings, is Hockney playing to his strengths (and perhaps exhibiting something like a 'late style' in Adorno and Said's sense): the continuation of traditional aesthetic concerns via new technological means, anachronistic, and for this very reason, able to cast a strange light on our contemporary relation to images.

Francis Plagne is a writer and musician from Melbourne

Title image: David Hockney, Untitled, 91, 2009, iPhone drawing. Collection of the artist © David Hockney)