David Egan, Green Seeks Little Attention

Amy May Stuart

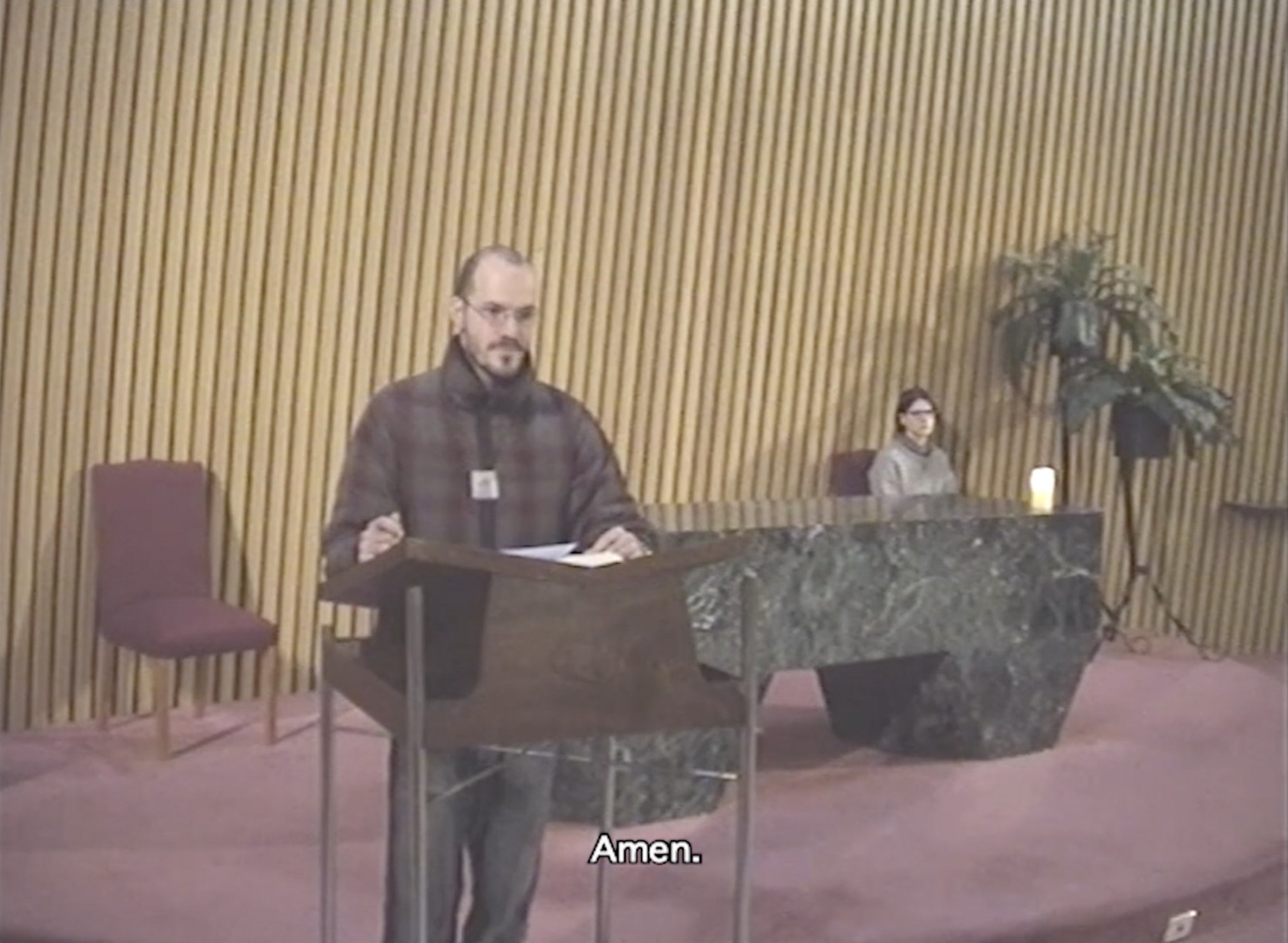

David Egan’s fifteen-minute-long video work, Crying Room (2019), immediately greets me as I walk into Haydens, a commercial gallery housed in a large Brunswick East warehouse complex. The solo exhibition, Green Seeks Little Attention, is the examinable outcome of Egan’s PhD research project. In the comparatively small front space, I sit down on what I recognise as a pew-like bench taken from the Fine Art post-graduate studio at Monash University. The video begins. I’m being sermonised by artist Ander Rennick (credited as Priest): “A voice says, ‘Cry out,’ and I ask, ‘What shall I cry out?’ All people are like grass and all their faithfulness is like the flowers of the field”. From behind the pulpit, Priest’s intoning seems important, and I diligently try to decode his meaning while continuing to listen. Acolyte (played by Brennan Olver aka musician Wet Kiss) sits quietly behind the Priest; between them sits a monolithic, green-marbled table. Priest continues, guiding us, his flock, with rhetorical questions and metaphors about nature, colours, time, life and death. He has the power to make numbers appear in the air as he lists them: a bright red “5” flashes, followed by a purple “8.”. “… The word of our God will stand forever,” he concludes. And looks up with a self-satisfied: “Amen”.

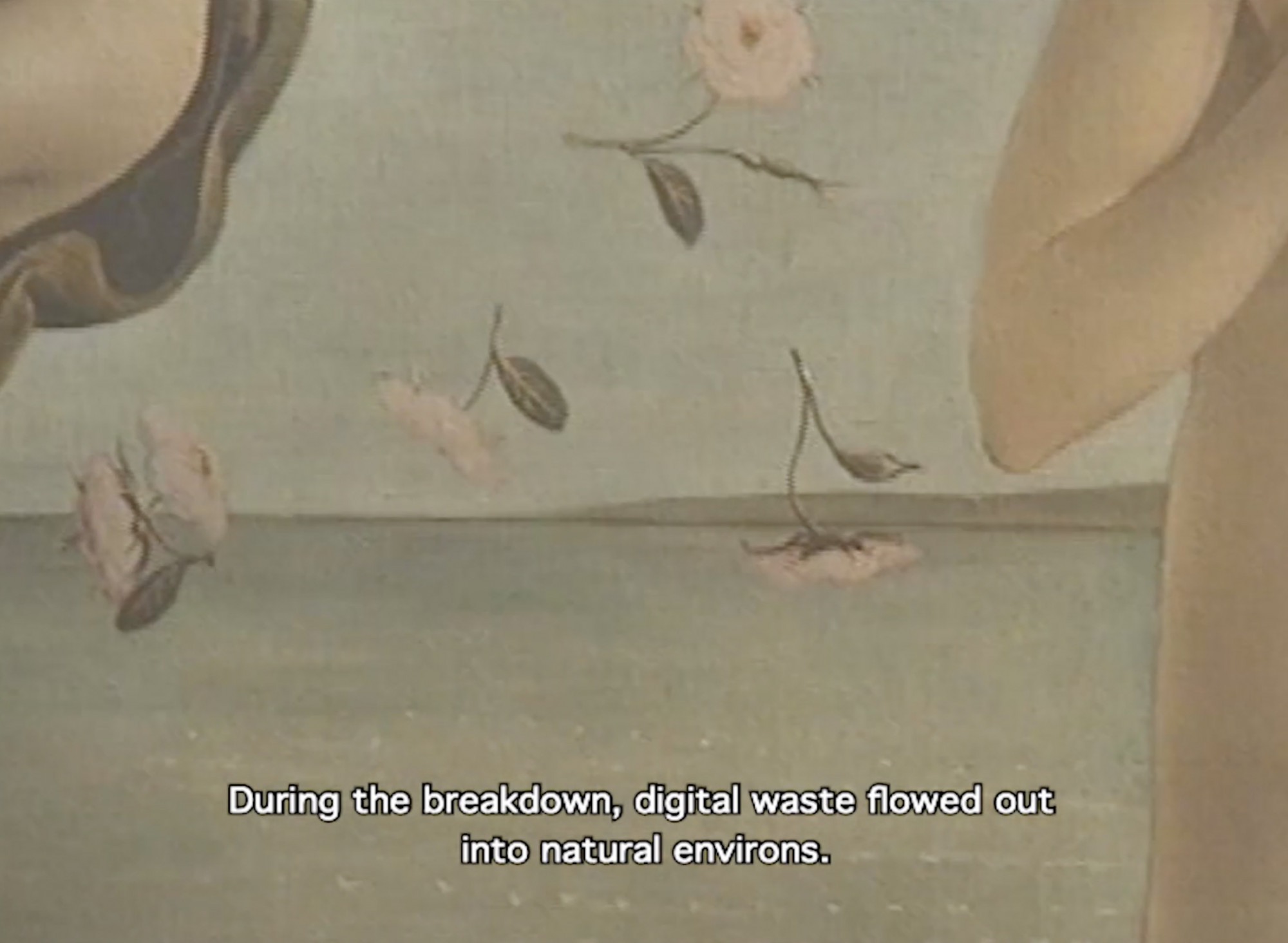

The video cuts and we hear Angel’s disembodied voiceover (by Kalinda Vary) giving a dreamy account of what could be Medieval-era worship in a Christian church. The swaying, hand-held camera traces tightly cropped panes of stained glass and frescoes of pilgrims, cherubim and plants. Synthy, metronomic music plays, sounding like it was lifted from a low budget 90s educational video. (It’s actually by the Perth band, Mental Powers). Angel’s hypnotic voice recalls a place glowing with coloured light and worshippers’ bodies dancing over tiled floors. The wobbling pan-and-zoom camerawork reanimates static images of bodies and flowers, like someone’s last, ecstatic moments before passing out from Stendhal syndrome.

Angel continues, describing the Church’s practice of “manufacturing belief and cultivating loving fathers”. As a cosmic being, Angel alludes to the tension between a cosmology accommodating a spiritual realm and the activities and motivations of the enduring institution known as the Church. I look to the exhibition text, which informs me that Egan was raised in a Charismatic Catholic Community, where “as an indoctrinated child he practised resting in the spirit, speaking in tongues and the gift of prophetic visions”. It goes on to position Egan as being vehemently critical of the coercion and abuse perpetrated by the Church, without disavowing his “indebtedness to its mystic aesthetic traditions”. I feel like I’m getting my bearings in preparation to enter the large gallery space ahead.

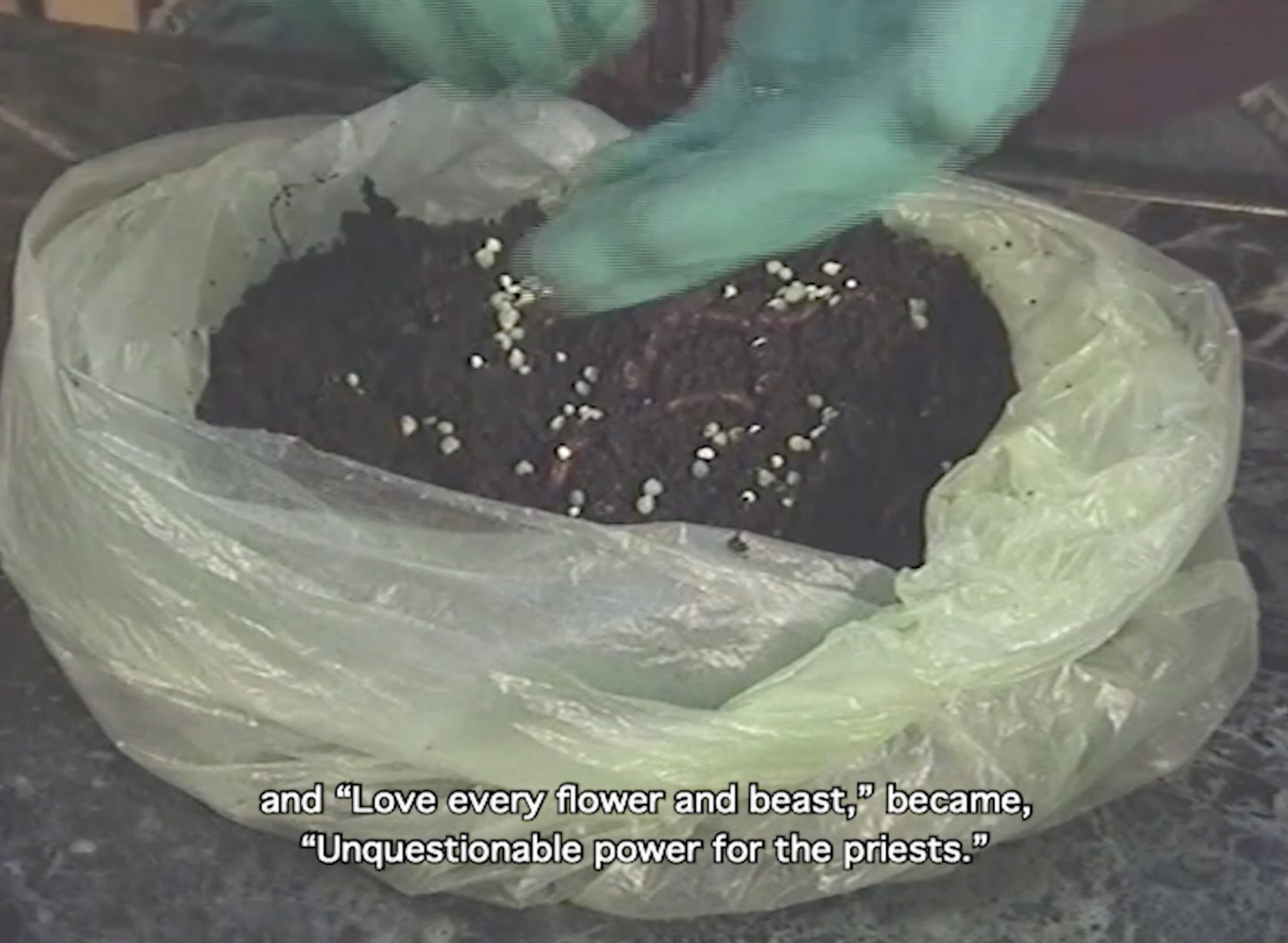

The scene changes and devotees Maisy and Del, played by artists Beth Maslen and Indiana Coole, face the camera in what appears to be another chamber of Priest’s church. The pair discuss childhood memories of faith and belief. Maisy feels there is a distinction between Christian figures such as Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny and guardian angels. Their conversation goes on as the camera cuts to Priest and Acolyte at the green-marbled table, attending to something peculiar—an object-based ritual. Hands in green chemical-resistant gloves are ceremoniously carrying out a prescribed sequence of events: sprinkling something into a dirt-filled bag, transferring a dark green liquid from one vessel to another. It’s a seed-planting ritual and as Priest hovers his hands over the bag, a small flowering plant is summoned forth. Angel’s voiceover returns, continuing her account of the Church’s ongoing wilful misinterpretation of divine messages sent from on high, to the frustration and dismay of angels everywhere.

The last characters to appear are Hubert (Wil Kalimba) and Margot (Clare Wöhlnick), conversing in a crying room. This unfortunately-named space is a common church fixture, a windowed annexe usually placed directly behind the pews of the main congregation. Crying rooms are (ideally) soundproof, allowing for un-silent parishioners—crying, wailing, screaming; often infants, but not always—and those accompanying them to maintain participation in church proceedings without disturbing the peace. Hubert and Margot debrief on a recent dizzying, transcendent group-experience facilitated by the church. Hubert earnestly recounts seeing mystical, whirling colours and communing with God, while Margot is more sceptical, suggesting that this could have been caused by the heat and stained-glass windows. Their speech is scattered with what I figure is future slang: carpet is “carp”, there are “vape vents” in the church and Margot announces that she needs to “fresh her cans”. These exact definitions are ambiguous, but that’s the point. Egan’s knowing inclusion of this familiar science-fiction trope repositions Priest and Acolyte in their botanical ritual as both devout members of the Church order and scientists.

With this science-fictional turn, the work revisits each vignette once more. Angel tells us that the angels have “gone virtual” and fled online, with the regrettable consequence of crashing the entire system. They attempt to avert eco-catastrophe with a last-ditch effort by transmogrifying into flowers. Del insists that the Church’s “growing programs” will save the Earth, but is interrupted by Angel speaking to them through a flower, announcing deliverance, imminent bee extinction and the heat death of the universe. Hubert convinces Margot to imbibe a shockingly organic (not plastic) flower, in the name of giving themselves over to Him, and they both vanish. Finally, Acolyte ascends a spiral staircase and begins to play a church organ, singing strange, disjointed lyrics about “her freshness”. Abruptly, Acolyte stops playing and the video is over.

Crying Room rapidly accumulates and slides between layers of temporality. Made in 2019, Crying Room’s materiality—the video quality and massive CRT television—explicitly references the 90s. So too, the film’s sets and props. Egan’s future-slang is retro-futuristic—it feels like watching Hackers (1995) or reading William Gibson’s proto-cyberpunk novel Neuromancer (1984) in 2021. There is an “online,” but it’s called the Netscape—a reference to the short-lived but highly popular early internet browser, active from 1994–2003. Hubert suggests that he and Margot ingest petals to extract the flower’s P.L.U.R. (those who know, will know). Inciting 90s nostalgia is currently at fever-pitch in popular culture; however, Egan sidesteps this with the unlikely mash-up of the history of Christianity, near-future climate apocalypse and the eventual heat death of the universe. Angel takes us through these events chronologically, while Priest and Acolyte combine religion and science like Renaissance polymaths. The stained glass and frescoes traced by the handheld camera seem, to my inexpert eye, surely Medieval. There is duration, too. Characters speak of the eternal realms of Hell and salvation, the impermanence of biological lifeforms in the face of God’s “forever,” and the hypothesised thermodynamic fizzling-out of the universe in around 102500 years.

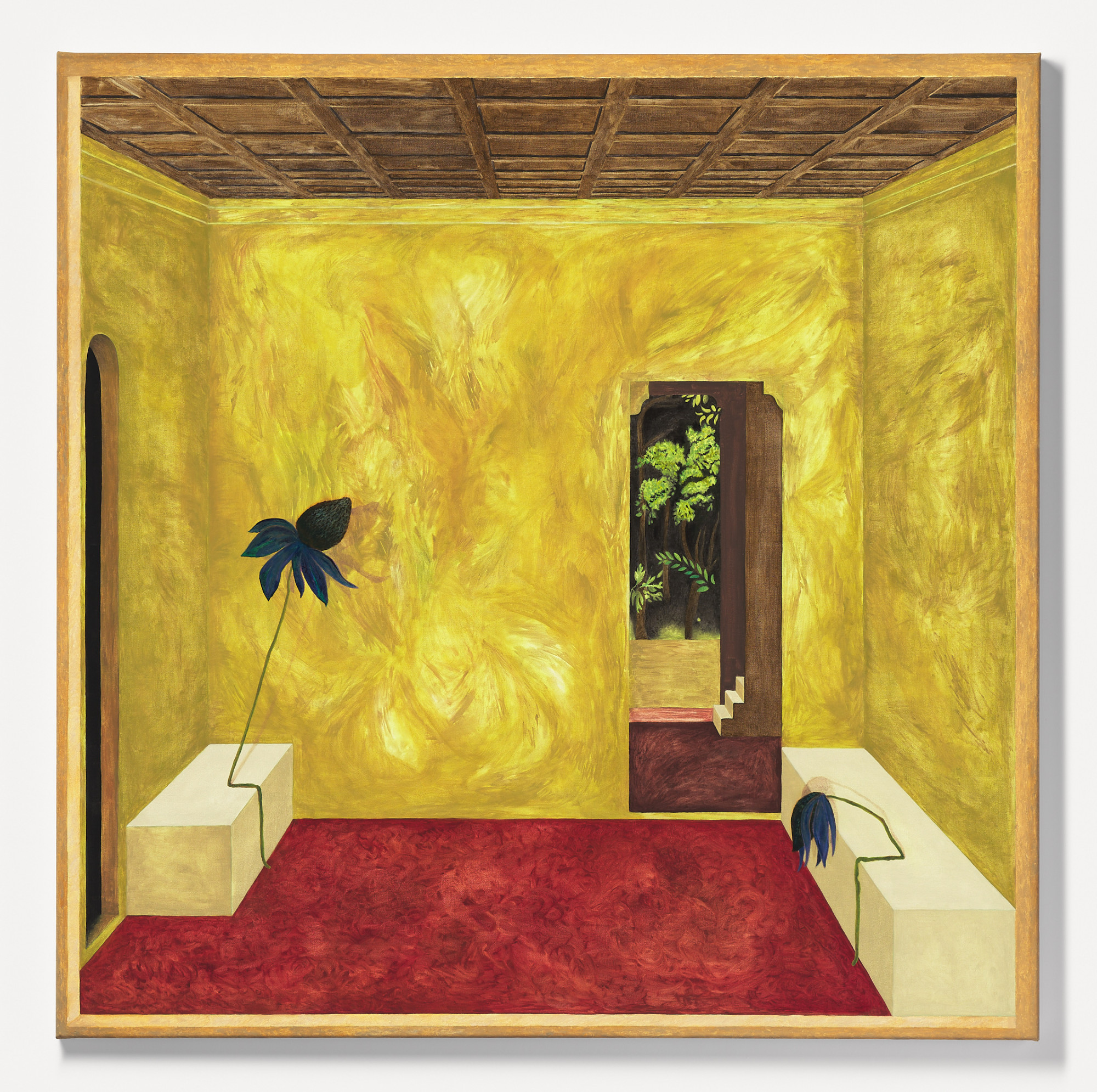

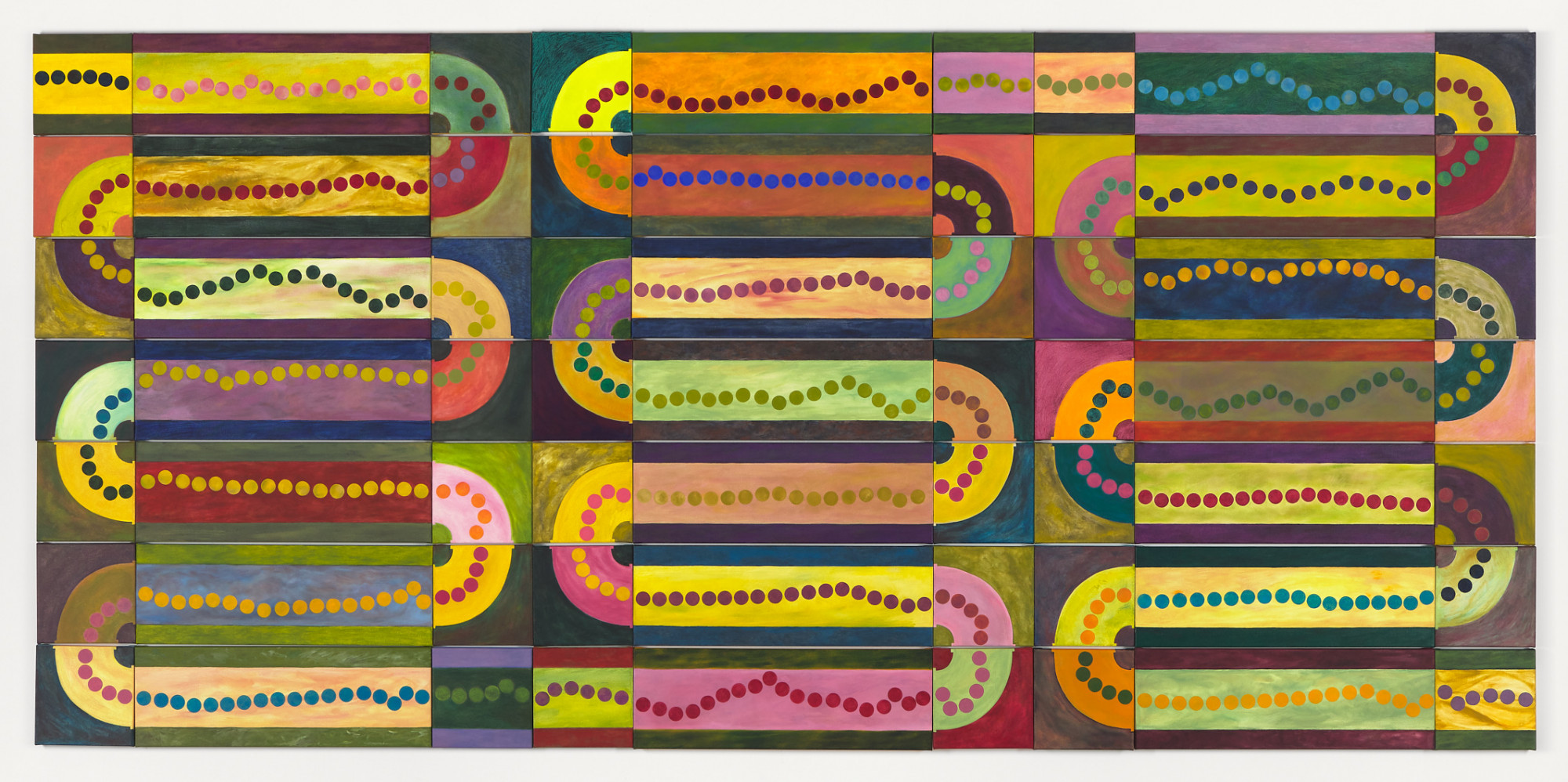

Wondering about the questions raised by “manufactured belief and cultivated loving fathers”, I walk into the main gallery. Acolyte’s song is stuck in my head, so I decide that Crying Room (2019) will be my educational video, a sensibility with which I’ll view the following works. There are large colourful paintings everywhere. Even over the door I just passed through hangs Cardinals (Vatican Sexual Abuse Summit) (2019). I recognise the reconfigured walls of Egan’s previous crying room installation, originally exhibited in its more claustrophobic, carpeted form at Sutton Projects in 2019. This time, Crying Room (open plan) (2019–2021) is open plan, no longer suffocating and its sole doorway has become obsolete. I notice that the tiny silica-gel beads held in the room’s windowsills have changed colour over time, but I can’t remember them fresh. The paintings shift between figuration and abstraction, often in a single work, with flowers and flower-like shapes, spheres, grids, faces, ears, feet and rooms appearing and disappearing amongst themselves. Egan’s meticulous, small, scrubby brushstrokes and layering of semi-opaque shapes unify the room. A procession of flat circles snakes their way, bead-like, through canvases of grotesque, stretched ears and diagrammatic pipes. Unlike the video, there are no 90s signposts here, nor overt references to the genre of science fiction (except in the naming of the paintings, which echo works by authors Kurt Vonnegut, Octavia Butler and Philip K. Dick). Rather, there are allusions to other paintings: a flower of Georgia O’Keeffe’s floats beneath dancing feet on a gridded floor in Here Below (2019). In another painting, I realise that Egan’s Back Room (2021) is a version of the Renaissance painter Fra Angelico’s Apparition of St. Francis at Arles (1429) (with humanoid flowers replace cowering monks). In my mind’s eye, the characters of the video try to find their places amongst the paintings, all finding something to rejoice or recoil from. I imagine Priest, clutching at his institutionally vested authority joining ranks with the tightly packed Cardinals above the doorway. Angel joyously teleports with Maisy through Conduits Between Realms (2021)—a kaleidoscopic series of dozens of modular canvases—while Del and Margot wander in limbo from painting to painting, trying to parse the impossible hot mess of faith, the Church, the abuse of power, love and knowledge.

Recalling the animism of the video’s talking flower, I’m suddenly summoned by a cream-coloured lectern in the corner of the space—the shock of recognition. “You know me,” it says. “You took me from the undergrad building at Monash and dragged me up to your studio, where I stood alone for years, covered in junk”. It’s true, but despite the complaining I don’t feel bad. My Mum, on the other hand, who grew up immersed in Japanese Shinto beliefs, would definitely have something to say about this. Shinto is polytheistic, and rather than having a central authority or doctrinal text it exists as a series of varying practices and beliefs that are integrated into everyday life—the main belief being the existence of animistic kami. Kami are supernatural, invisible beings that inhabit all things, animate, inanimate, natural forces and events. While they don’t necessarily communicate via language, my Mum definitely ascribes a kami life-force to things like fried eggs (“Amy, your egg is crying and waiting for you”), hard rubbish (feeling sorry for it and taking it home) or the Moon. I sense that Egan also holds an appreciation for the animistic or numinous forces existing in Christian belief, especially regarding a reverence for and stewardship of nature. Del’s flower and Angel’s invisible but insistent presence has allowed me to become attuned to the lectern’s kami, which is low-key mad at me.

I walk over to the lectern and find one of Aodhan Madden’s three short texts (all published in 2018, 2019 and 2021), which are printed pages hung amongst the paintings. The first two that I read are poetic musings and vignettes which sit alongside the works, rather than telling us how to read them. The third, placed on the “inside” of Crying Room (open plan) is similarly ambiguous and metaphorical but the content is infinitely darker. In my interpretation, the text narrates an account or memory of sexual assault by a clergyman and its attendant traumatic effects. It’s a deeply unsettling note to exit the exhibition on, but a crushingly real one. Passing underneath the bastion of cardinals once again, I think of the ongoing and incommensurable damage wrought by one of the most powerful institutions in the world. In Egan’s paintings and video, I sense his connection to and appreciation of Christianity on the one hand, and on the other, his anti-institutional and moral rejection of the Church. I remember Maisy’s guardian angel whom she cherishes, but who is also creepily described as someone who follows you around always, watching and knowing everything you do. A product of years of consideration, Green Seeks Little Attention is a fascinating, painterly study in holding these lurching and contradictory cosmological beliefs together, in the full techno-scientific and religious senses of the term.

Amy May Stuart is an artist living in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia.