Claire Lambe, Dart Object and Jemi Gale, drowning curse

Audrey Schmidt

Jemi Gale’s drowning curse occupies one half of the TCB gallery space and includes collaborative paintings with Aida Azin, Alexandra Nemarič, Brayden Van Meurs, Krishan Meepe, Levi Neeson, Luci Avard, Matthew Harris, Panda Wong, Ruby Fitzgerald, Sol Fernandez and the elusive “(Artist name withheld)”. Flanked by the paintings, at the centre of this space sits a large wooden box lined with clear plastic and filled with approximately eighty litres of Mountain Dew. At the time of my visit, untitled (drowning curse pool) by Gale with fabrication by Alexandra Nemarič was soaking the corners of its container and spilling through the cracks onto the gallery floor. Still bubbling, with the odd pop at the surface, the fizz is destined to go flat and leak sticky artificial yellow liquid like nuclear waste, attracting insects and escaping its trough-like confines. There was only one vantage point from which to successfully step over the spillage and view the paintings on the far wall at obligatory close proximity.

The loosely citrus flavoured soda was once dubbed the sperm-killer on account of its higher than average caffeine content and yellow dye. While there has been no evidence to support this conspiratorial contraceptive theory, as is often the case the truth is more alarming than the fiction. There is such a phenomenon as “Mountain Dew mouth”—the name public health advocates gave to the alarmingly high incidence of tooth rot in Appalachia, the region that stretches roughly from southern New York state to Alabama and where the drink of choice is Mountain Dew. With the dental solution often being tooth extraction for those who can’t afford dental care, dentists describe the effect of soda on teeth as being strikingly similar to the effects of methamphetamine or crack. I can still see the teeth of the nineteen-year-old Kentucky man, in the gimmicky documentary bordering on poorsploitation That Sugar Film (2014), who would have twenty-six extractions after drinking twelve cans of Mountain Dew a day since the age of two.

There’s something about Mountain Dew that hints at the passage of time. In drowning curse, the wooden trough slowly absorbs and takes over the gallery floor like that raspberry jello Red Menace in the Chuck Russell directed horror-sci-fi film, The Blob. Some of the Band-Aid wrappers haphazardly strewn across the floor had already been engulfed by the substance and subsumed into the (untitled) drowning curse pool materials list. In keeping with a little taster of communist desire, each of the paintings is collaborative, mostly developed during peak Victorian lockdown with some done by post and others worked on in tandem, often in several iterations or drafts.

The chaotic multi-layered paintings are each distinct despite their kindred garish colour palettes. One, a collaboration between Gale and Ruby Fitzgerald, entitled i’m spiralling, shows layers upon layers of spirals and stream-of-consciousness markings that come up more brown, more dark or more distraught than for example her more cutesy-pop collaborations with Sol Fernandez (whats in my head) or Luci Avard (i am weary of my crying: my throat is dried: mine eyes fail while i wait for my god). The diaristic first-person internal monologue titles belie their collaborative nature—a joint confession of individual suffering.

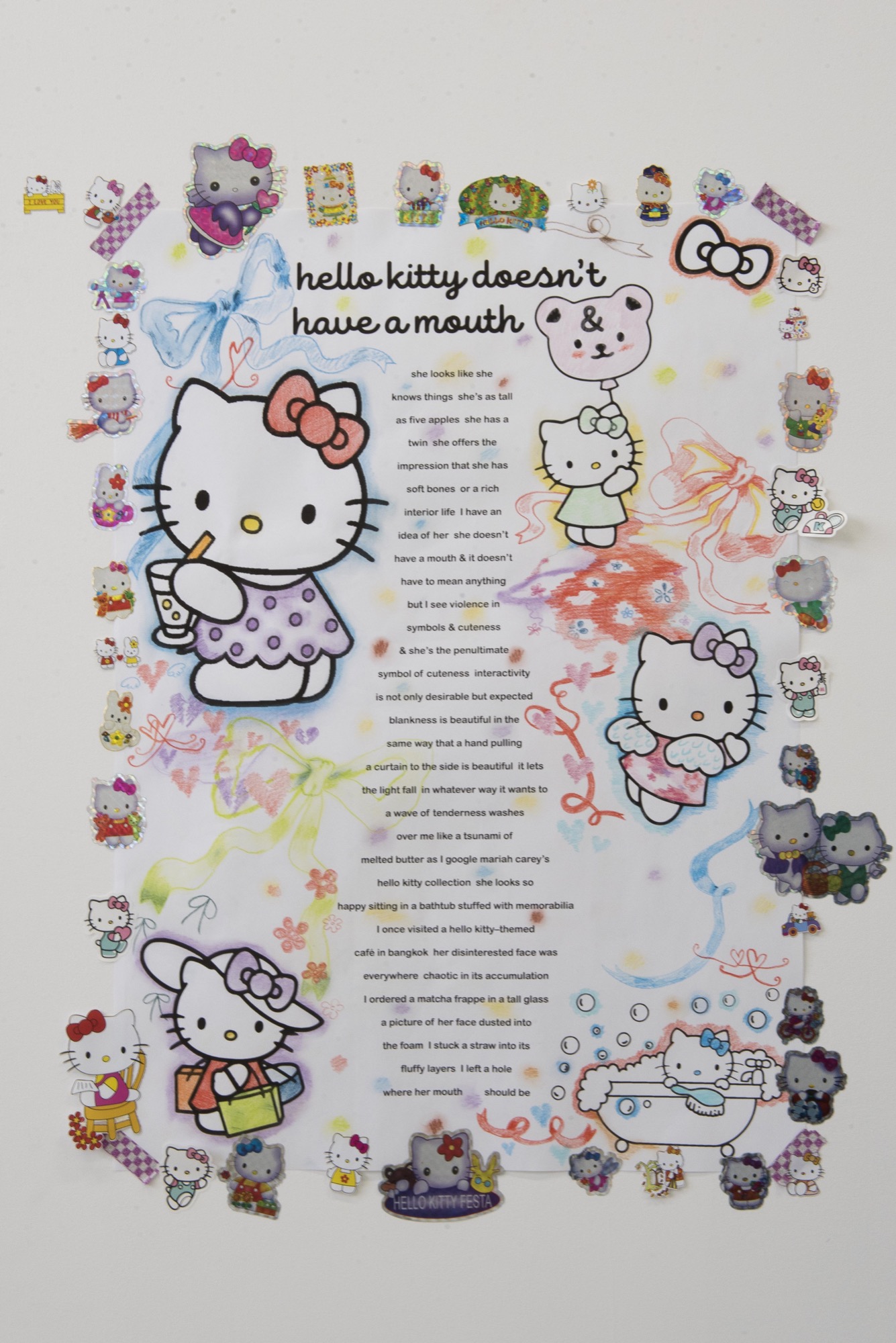

Panda Wong’s poem hello kitty doesn’t have a mouth is presented as a wall decal and drawing surrounded by kawaii stickers of the character installed by Gale. The perfect commodity, it is an icon of consumerism that exists only as merchandise, which first appeared on a vinyl coin purse and was only tied to manga or anime narratives as an afterthought. The Sanrio company did not give Hello Kitty a mouth with the express purpose that consumers should “project their feelings onto the character” and “be happy or sad together with Hello Kitty”. Wong’s poem ends with poking a hole into Hello Kitty’s likeness “dusted into the foam” of a matcha frappe with a straw where her mouth should be.

Speaking to the leaky Mountain Dew and Hello Kitty’s punctured frothy visage, a collaboration with Brayden Van Meurs features Band-Aids slapped onto the canvas that were presumably extracted from their discarded floor-work sheaths. While this could be a comment on “the healing power of art”, the hurried, almost frantic, non-disposal of the wrappers makes it feel more like a quick fix. It is like the bloody moment before things can coagulate and heal or that meme where the guy slaps a piece of Flex Tape over a hole spilling water from a giant transparent cylinder.

Reaching towards the other half of the gallery, the pool of Mountain Dew threatens to collapse the two sides of the artificially divided space. It’s headed towards an eiderdown jacket designed in 1939 by Charles James for the wife of American businessman Oliver Burr Jennings. This is the centrepiece of Claire Lambe’s leg of the exhibition entitled Dart Object. Based on the principles of a bed quilt, James’ evening jacket is considered to be the first “fashion puffer” and had a re-life in the 1970s with items such as Norma Kamali’s sleeping bag coat, which prompted James to write a full description of the development of his design. It is from these archival documents and images that Lambe has painstakingly re-birthed a replica of the jacket. She has carefully estimated its scale, texture and weight from descriptions of padding, necklines and armholes, watching YouTube tutorials, overstuffing sections, making, unmaking and remaking. It is a processual, in-depth and lived analysis of an object of desire—a desire that, in its very nature, is a fluid, non-linear, moving process.

John Berger wrote in his 1953 essay, ‘Drawing is Discovery’, that the “shorthand” of drawings, their simplicity and directness, is concerned primarily with the artist’s own, private, needs. “It is this”, he writes, “which explains why painters always value so highly the drawings of the masters they admire and why the general public find it so difficult to appreciate drawings”. In front of a drawing, you identify with the artist, straining to see this unfolding movement through their eyes. From Berger’s perspective, drawing is therefore an “unfurnished idea”, a draft that remains open to the possibilities of its future completion—a moment in time that assuredly spills over the limits of that moment. In this way, a drawing is like a journal—a record of the artist’s discovery of their subject matter, with its textual equivalent being diary writing.

Dart Object contains only two other comparatively understated images. A still from Claire Denis’ nostalgic film US Go Home (1994), where desire meets repression—a close-up of a kiss meeting bread dough—and an archival fashion shoot of a dress on a mannequin against a pink paper roll backdrop. These are images that complement the Charles James jacket as a record of studies driven by form and material as tractile, lived and felt processes. In her 2017 solo exhibition at ACCA, Mother Holding Something Horrific, Lambe reconstructed Sigmund Freud’s chair—another form made to hold a specific body, one that needs the body to function but that has been obscured by image circulation and archival abstractions and then recreated based on those mediated remnants. Although more expansive and image-rich, Mother Holding Something Horrific was a diaristic insight into Lambe’s process-based practice, likewise dealing with lived tactility and form. Populated with collected “reference” images and remakes, it forms a view of history that always already entails a sense of the future—where nothing is immune from development or iteration. Dart Object, like drawing, is an archival or historical account grounded in sociocultural specificity, and yet it leans on its immediacy as a personal process, draft or journal.

In writing, the distinction between revision and composition began to erode with word processing technology. As Nietzsche typed on a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, a strange spherical contraption cast in brass and studded with typewriter keys: “our writing instruments are also working on our thoughts”. Now entire manuscripts are available to us via search functions: paragraphs can be cut, pasted and reordered at will. The textual field became as malleable and infinitely expansive as a never-ending Word document.

As opposed to lamenting the good old days of parchment and ink, perhaps the limitless Word document is more in-tune with the creative process. This sentence has probably been moved several times before you came to read it. And even now it’s published, online or in print, it’s not set in stone. Someone once told me that a good artist will endlessly rework, reimagine and reinvent the same material over the course of their career. The same could be said of writing (I have already reused old writing in this text). Works do not cease to be “in-progress”. The journal is a tool or a steppingstone to a larger, more refined work, but that work is itself a kind of draft or journal. For both Gale and Lambe, the fluid nature of history, of time, desire and encounters, seeps through the cracks in the archive, not to give us something like evolutionary progressivism hurtling towards some final totality (nor away from some primordial one), but something more aligned with a Deleuzian becoming—inscribing life within an irreducible and nonclosed temporal dimension. It is like the Flex Tape slapped on desire’s unstoppable deluge and the promise of drowning.

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and Melbourne Personality.