REALTIME: Miyanaga Akira; Daniel Crooks: Parabolic

Kate Warren

The growth of the large metropolitan cities of modernity occurred largely alongside the invention and proliferation of camera technologies in the nineteenth century. It is therefore not surprising that many of the earliest, and most iconic images from the histories of photography and cinema feature cities or urban environments. Think of Louis Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple (1838) and the Lumière Brothers’ first “actuality” films, such as L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1895). Even the foundation story of video art involves Nam June Paik taking his newly purchased Portapak camera onto the packed streets of New York City to document the visit of Pope Paul VI in 1965 – along with all the traffic jams and urban disruptions caused.

The patterns and rhythms of urban culture have proved rich inspiration for generations of artists and filmmakers. Two exhibitions in Melbourne reveal that these connections between urban environments, cameras and technological experimentation remain of keen interest to many contemporary artists. Daniel Crooks’ Parabolic at Anna Schwartz Gallery and Miyanaga Akira’s REALTIME at the National Gallery of Victoria present two artists working with similar inspirations, and many similar techniques, but to quite different effects and ends.

If one thing came through most strongly seeing these two exhibitions at the same time, it was the fascination with the temporalities of urban life and the movements of bodies in urban spaces. New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based artist Daniel Crooks has been exploring these relationships since the early 2000s, when he started experimenting with his now characteristic “timeslice” technique of video editing. As the exhibition’s title suggests, the videos in Parabolic transform the urban environment with curves, waves, parabolas and space–time distortions. They take the movements and rhythms of urban spaces as their raw materials. Crooks does not move his camera through these spaces though; he decides on a particular vantage point, and lets these movements unfold around him. In post-production, he then performs his own processes of unfolding and unravelling these scenes. By extracting thin slices from the video and then recombining them, Crooks’ scenes morph and stretch in unpredictable ways. Bodies, people and buildings are transformed into moving smears of colour, texture and time – seemingly occupying multiple temporalities at once.

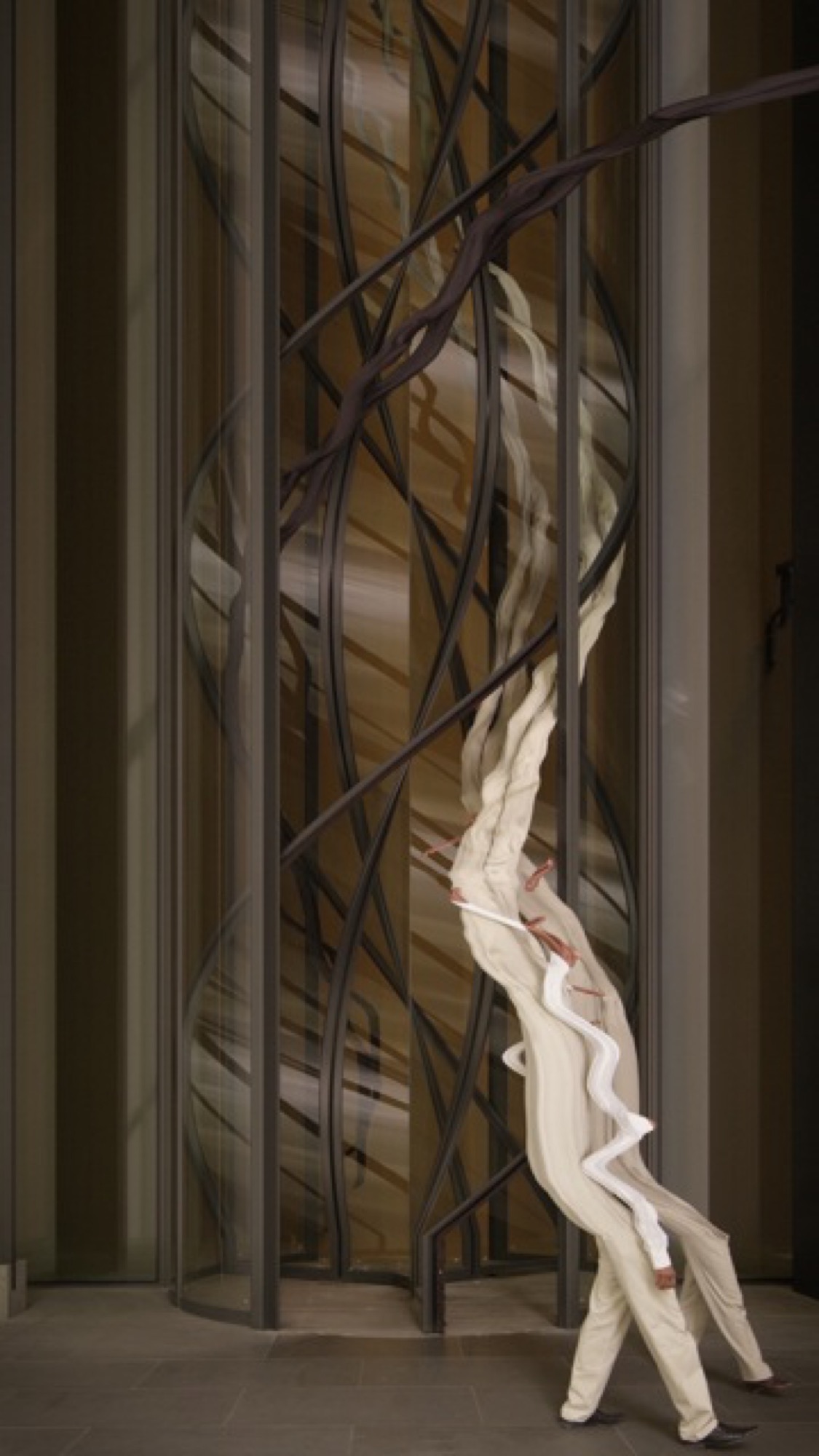

In this new body of work, two videos stood out in their clever application of Crooks’ characteristic slicings. Featuring a street scene in Hong Kong, Static No.22 (Gyre and Gimbal) (2017) is presented as a circular image. Crooks disrupts the scene with digital waves, like ripples radiating in a pond, ripples from which stretched human figures emerge. The effect is like birthing urban dwellers from an invisible portal. Static No.20 (Archimedes Screw) (2017) frames a large revolving door, a perfect muse for Crooks’ time slice. As its slow, regular, circular movements are stretched upwards, they create a web of helixes, curves and intersections that increase in abstraction as the video progresses.

Parabolic shows clearly the lengths to which Crooks has been perfecting this timeslice technique – which is a very simple concept that requires complex and dextrous execution. He has an exceptionally clear and precise visual language, and his latest offerings reveal that the urban environment provides an almost endless array of viewpoints, microcosms and moments in time for the artist to transform. Technological proficiency and process are crucial in enabling the captivating effects of Crooks’ videos; yet paradoxically these elements are so central to his practice that they sometimes risk overwhelming its wider and ongoing reception. There were many moments of surprise and delight within the individual videos in Parabolic, yet also a sense of a return to somewhat familiar terrain.

If Crooks’ works are astoundingly precise, Hokkaido-born and Kyoto-based artist Miyanaga Akira’s videos were rougher and slightly less polished. Miyanaga takes similar inspiration from contemporary urban environments, constructing videos from footage of everyday scenes, and using similar post-production techniques of timelapse, splicing and superimposition. Miyanaga’s videos, however, were more immediately disorientating to the viewer, with many works constructed through clever doublings of shots and screens. The exhibition’s first video, See Saw (2015), presented a passage across a suspension bridge, the footage tilted and mirrored to give the impression of levitating and hurtling through the space. The duo of screen-based pieces Angles and See Same Sky (both 2015) presented similarly contorted passages through the urban environment. The passing views of skyscrapers, trees and various urban structures – possibly taken through a car window – were each densely layered with other imagery, creating highly fragmented and abstracted transits.

Both Crooks and Miyanaga investigate and confound perceptions of time and space in contemporary urban environments. Despite their similar inspirations and technical processes, they end up conveying quite different understandings of temporality. In Crooks’ hands time is exceedingly flexible; it stretches and contracts, unfolds and refolds, and so transforms the metropolis and its inhabitants into otherworldly entities. Miyanaga’s videos speak to a more overwhelming and expansive experience of time and space in urban centres. The videos in REALTIME exploited and amplified the intensities and cacophonies of urban space, although I had the sense that this aural element could have been amplified and emphasised more in the exhibition’s installation. The decision to project most works onto white walls disappointingly washed out some of the striking visuals.

Miyanaga’s videos took the surfaces, textures, sounds and views of the city, stitching them into dense, layered digital tapestries of urban environments. Yet in their expansiveness they at times lacked the sense of suspense and discovery that characterised Crooks’ works. The exception was the exhibition’s namesake piece, REALTIME-MATERIEL (2015). Perhaps this was because, like Crooks’ works, it centrally features bodies in space, as opposed to detached cameras moving through anonymous urban milieus. The video presents a highly recognisable and identifiable scene – a crowded Japanese subway station. Using timelapse photography, Miyanaga speeds up the already hectic movements until all the figures dissolve into a large tableau of refracted light and colours. It is telling that both artists resort to abstraction ultimately to depict their fascination with urban spaces. Miyanaga’s abstractions remain more closely tied to their referents, the city as a force of inspiration and alienation. Crooks takes this further. His temporal and visual slicing and morphing begin to exceed their urban subjects, creating a visual language drawn from the rhythms of the city, but somehow apart from it at the same time.

Kate Warren is a writer, curator and researcher based in Melbourne, with a particular interest in cross-overs between contemporary art, film, photography and moving image practices. She received her PhD in Art History from Monash University in 2016.Title image Daniel Crooks, Parabolic (installation view). Image courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery )