The Sun also Sets

Luke Smythe

In his latest exhibition at Tolarno Galleries, Danie Mellor continues to use Western modes of picturing to address the impact of colonisation on his Indigenous forebears. Mellor has Mamu and Ngadjon ancestry and uses drawing, photography, and sculpture to reflect on the losses both groups have sustained as a result of European invasion. He typically sets his works on their Country in Northern Queensland, in what is now the Tablelands rainforest.

The twelve works shown this year include four new photomontages of a kind Mellor has been making for several years. Printed on metallic paper and again set in the Tablelands, these composites show the faces of local men (and, in one case, a skull) blended with and gazing out from dense foliage. The faces are derived from archival photographs taken at the turn of the last century by colonial photographers. Mellor made the photographs of foliage himself using an infrared camera, a technique that turns foliage stark white, giving the forest an irradiated quality that contrasts strongly with the shadows and dark skin tones in the archival images. The merger of the two produces haunting and enigmatic fusions of people and Country.

As is typical for art based on historical photographs, Mellor’s composites feel proximate and distant at the same time: proximate by virtue of photography’s indexical character and the uncanny sense of presence this provides, distant by virtue of the signs of age the photos exhibit and Mellor’s spectral blending of his sources. This strange sense of immediate remoteness raises questions about absence and presence that our historical beliefs and ontologies will incline us to respond to in certain ways. Has the unity of people and Country that Mellor’s compositions evoke now been irretrievably lost? Or has it merely been disrupted and attenuated? If so, can it be recovered and is that process already underway? Have the ancestors depicted disappeared entirely from the world or do they live on in another form, in the memories of the living, for example, or in the time-space of their Dreaming? The works provide no answers to such questions. Rather, their value lies in their capacity to provoke them.

The montages could anchor an exhibition in their own right, but the bulk of The Sun Also Sets was given over to a new group of works: paintings in acrylic with a final coat of iridescent wash. Based entirely on archival photographs, they also depict people and Country, but their iconographic reach is more extensive. In addition to figure studies and pure landscapes, they depict abandoned shelters in the bush and an excavated skeleton. They also vary widely in their staging and encourage varied forms of engagement.

In On the edge of darkness (the sun also sets) (2020), an Indigenous man looks out across a wide expanse of water. In the distance, a European settlement is visible, behind which a setting sun is beginning to slip from view. The man isn’t looking at the settlement but instead stares at the surface of the water, evidently lost in contemplation. The painting is a panoramic triptych we are invited to step into. But will we accept the invitation? Were we to cross the painting’s threshold and make our way toward its protagonist, our presence might interrupt his reverie. Perhaps we should hang back then and leave him to his state of contemplation. A third possibility would be to enter the scene unobtrusively and quietly take a seat alongside him, keeping him company and sharing something of his experience. Sadly, this scenario of quiet and reflective co-existence was something nineteenth-century invaders made little or no effort to facilitate.

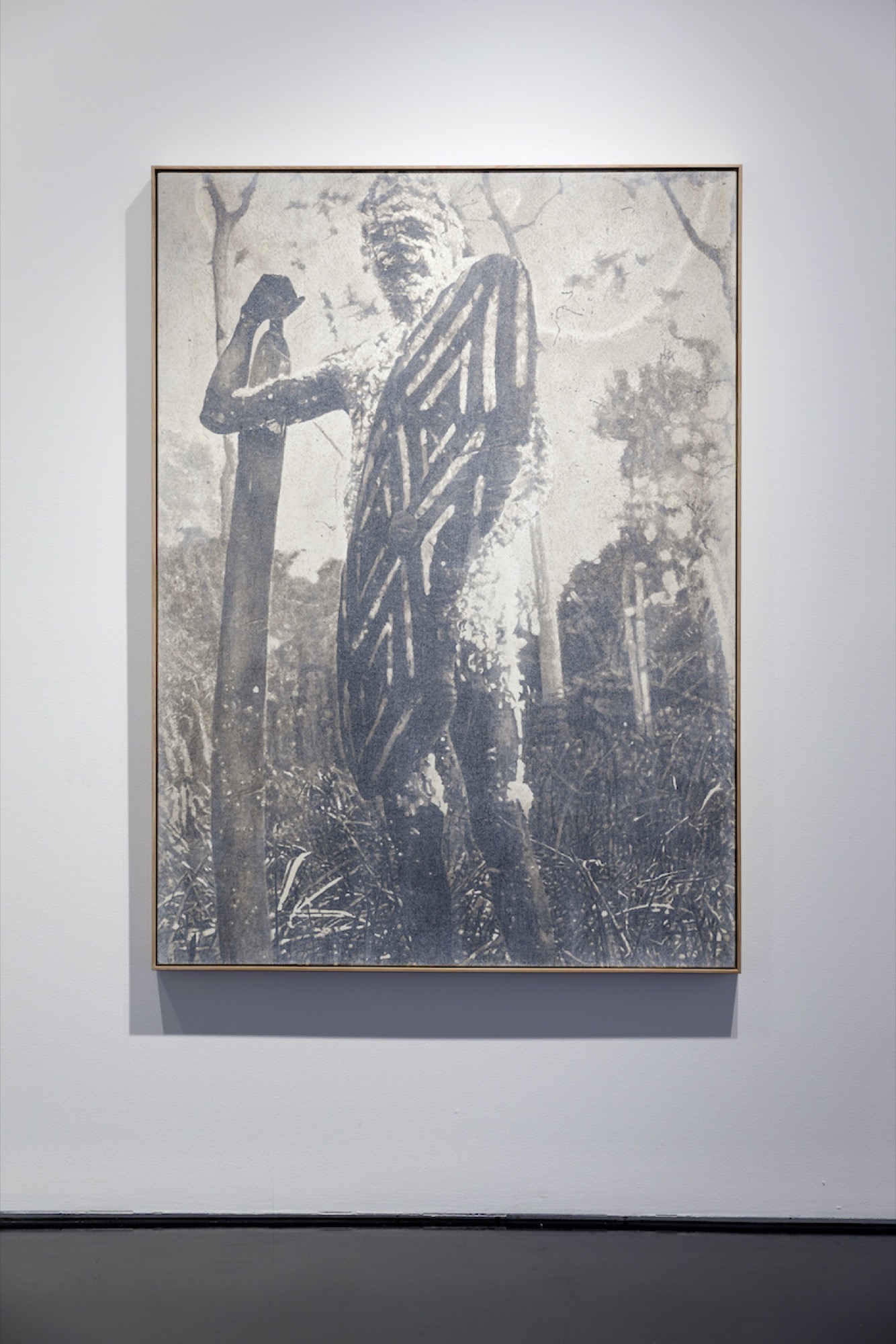

A question of being (2020) flips its lone male figure round to face us, then zooms in so he dominates the frame. He rises up before us in ceremonial attire, but his bearing is ambiguous. Is he proudly displaying his shield and the feathers that adorn his body? Or does the way he holds the shield out in front of him suggest a more defensive demeanour? Given the challenges his culture was facing when the work’s source photograph was taken, both sentiments are plausible. Since it’s hard to read his facial expression and information about the photograph is limited, this ambiguity is likely to persist. In his statement accompanying the show, Mellor says it was shown to him by a rainforest elder and attributes it to the German anthropologist Walter Roth. However, this attribution is unconfirmed and the relationship between subject and photographer cannot be determined precisely.

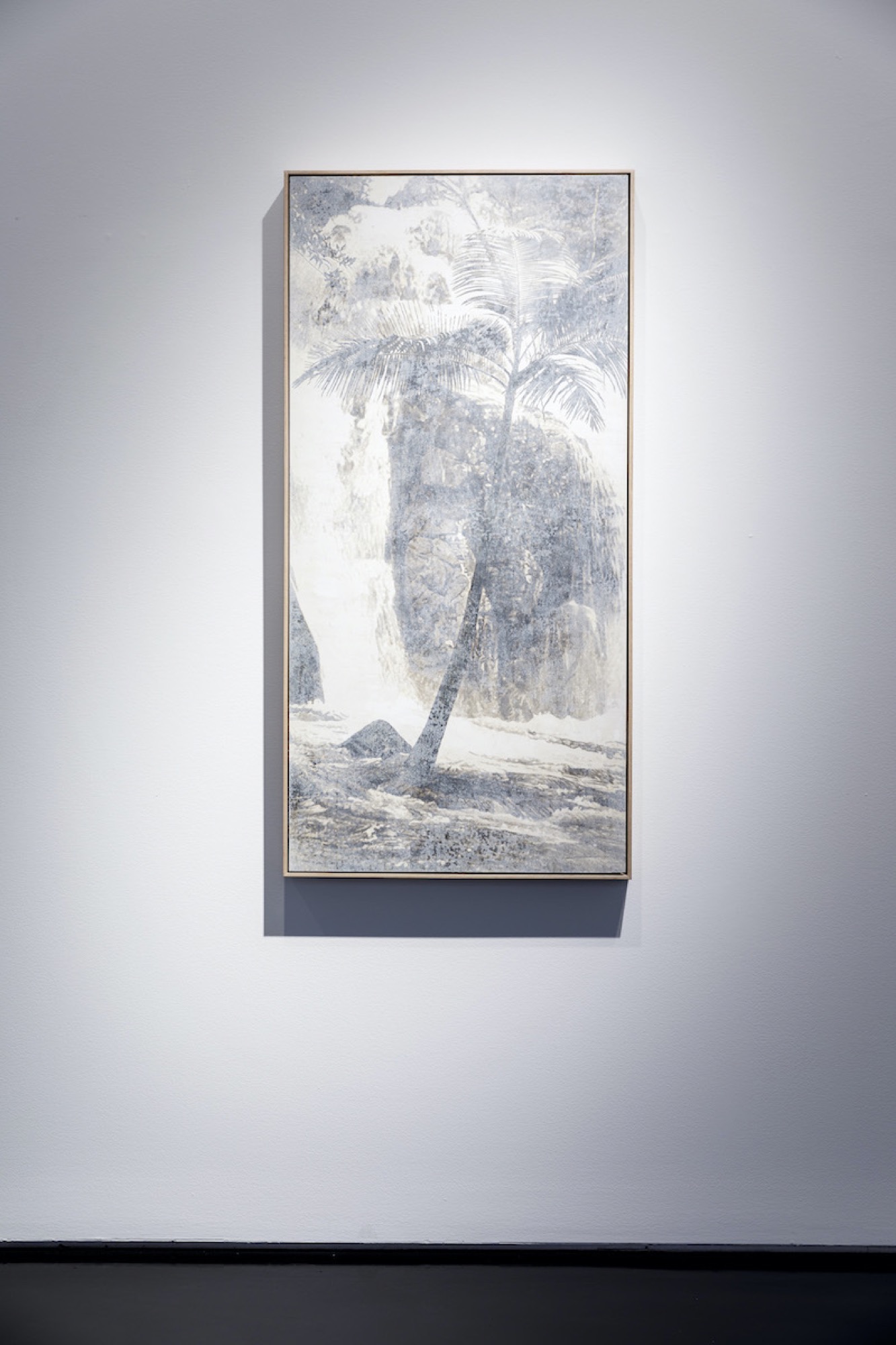

Two works without figures dare us to dismiss them by virtue of their sheer conventionality. The Photograph (2020) depicts a palm tree in streaming sunlight rising up from the rushing rapids at the base of a waterfall. Against the dying of the light (2020) unfurls a deep and shining vista of river, hills and bushland that retreats into a haze. Compositionally, both feel emblematic to the point of cliché of the romanticising European gaze. The former recalls tropical postcards at their most generic. The latter has a painterly feel, reminiscent of the Hudson River School. Both could be dismissed as kitsch or be read as yet another critique of landscapes with no Indigenous presence. To my eye, however, they read as celebrations of natural beauty, which remind us that Western photographic records from the colonial era don’t always reveal the impulse to dominate.

Mellor’s painting technique clearly has a role to play in marshalling such responses. Like Luc Tuymans and Gerhard Richter before him, he strips fine details from the photographs he copies. This device is well-suited to conveying effects of loss and distance, imbuing his scenes with an air of frail beauty. Their sepia toning reinforces these qualities, as does their washed-out appearance and the delicacy of Mellor’s paintwork, which consists of a patient accumulation of feathered strokes and dabs. I’ve encountered these effects and procedures elsewhere, but the iridescent wash Mellor adds to his finished compositions is new to me. Perhaps the glinting interference of this pigment enhances the enigma of his images, but as I’ve only seen them in the exhibition’s online viewing room I can’t confirm this. The photos of the works are excellent and allow for a reasonably close inspection of their surfaces. Their sheen has been removed, however, as have the effects of changing light.

These constraints aside, the viewing room experience was enjoyable. Not only were the works well photographed but also a series of installation shots, with a figure in the frame for scale, gave a sense of how an in situ encounter might unfold. Short texts by the artist and Tony Magnusson provided useful background on the work and offered worthwhile lines of interpretation. There was also a promotional video in which Mellor talked with Tyson Yunkaporta (Apalech Clan, Cape York), a lecturer from Deakin University. This too was informative and featured an amusing exchange of photographs across the split-screen that divides the speakers from each other. Due to Victoria’s ongoing border closure, Yunkaporta was filmed in Melbourne and the artist in his New South Wales studio. This material helped to market the show of course, with most of the works having sold at healthy prices. With luck, some have gone to public institutions and will soon have an in-person audience.

Viewers are unlikely to feel challenged by Mellor’s latest works, which explore familiar themes of historical dispossession and injustice using familiar techniques. They reward patient scrutiny, thanks to Mellor’s assured eye for composition and his knack for productive ambiguity. Some may favour a more strident approach in art that addresses past iniquities, but there is also a place for calmer works like Mellor’s, which draw us in instead of setting us on our heels.

Luke Smythe is a lecturer in art history and theory at Monash University. His book Gretchen Albrecht: Between Gesture and Geometry was published this year by Massey University Press. A book on Gerhard Richter is forthcoming.