Dale Frank

Kylie King

Any presentation of Dale Frank's work could easily be passed off as a prime prop for Instagram ops. His paintings—dazzling in size and colour, slick and hyper-reflective—demand attention and entertain. Yet they are also unsettlingly grotesque and possess an overarching posture of cool detachment. Indeed, his current exhibition at Neon Parc is as much confronting as it is alluring.

Neon Parc represents artists who could be considered materially transgressive, playful, absurdist. Frank's work embodies these traits along with a melding of interests in, and experimentations with, the physicality and possibilities of materials. Through an exploration of the potential effects that can be created with various material finishes, Frank expounds and utilises their powers.

This is apparent in the twenty-two works in this exhibition, which also follow closely—both in style and sentiment those included in his first exhibition with this gallery in late 2015, which Memo Review critic Amelia Winata astutely reviewed in Art Monthly as a didactic metaphor for hedonism in contemporary society.

Frank started his career in the late 1970s as a performance artist whose performances were, as Robert Lindsay wrote in the catalogue of the National Gallery of Victoria's 1983 exhibition Vox Pop – Into the Eighties, “very personal, non theatrical … hypnotic trance-like, disjointed aphasic utterances unfolding intimate memories of almost forgotten obsessions.” As his career progressed into the 80s and 90s, he transferred his own self-reflection onto paper and canvas, producing a number of (distorted) self-portraits and automatic drawings and paintings, which, composed of dark swirling lines, were atmospherically oppressive and introspective.

Looking back at Frank's experimentation with materials, this exhibition comes across as a culmination of a long-term seeking for a higher-sheen, more enhanced reflection and smoother, more seamless fluidity: by the 2000s, Frank started experimenting with more lustrous varnishes on linen, before moving towards polished, shiny surfaces such as Perspex. Indeed, the performative, technical and conceptual aspects of these early works can still be seen in his current paintings—thick, vitreous paints and varnishes pool, stretch, drip and flow across the 'picture' planes, contracting and expanding to create subtle vortexes of energy and the almost demiurgic manipulation of whatever is caught within them. But rather than taking the landscapes of his own inner worlds as his subject, Frank now turns on the viewer, forcing them to consider images of their own (distorted) self.

Frank's paintings are psychologically and physically intense. Drawn in by the glossy finishes of large reflective panels, the viewer notices their own reflection, and suddenly, the object imposes itself on them—the gaze is reversed, the viewer, instead, is gazed upon and re-interpreted by the object itself. In contrast to the traditional viewer-painting relationship, in which the viewer is active and the painting is passive, Frank's paintings make the viewer their subject—a reversal that is all the more starkly exposing under the uniform harshness of the artificial lighting in the gallery space. The distorted effects in the reflections of one's face and body, warped by the calculated application of poured vitreous fluids (Epoxyglass, liquid glass, and varnish) over Perspex backings, is both alluring and disconcerting. Relishing one's own reflection and the sumptuous visual material in front of them, the viewer is, in turn, engulfed, swallowed up, and overwhelmed by the very sensory indulgence offered to them. Frank draws attention to our narcissistic temptation through the title of one highly reflective work, Sometimes it is just a matter of telling yourself that you are in control.

The artist possesses a studied understanding of the capabilities of the materials that he uses. By rendering the surfaces of his paintings in the likeness of commercial finishes in his monochromatic paintings, for example, Frank draws a comparison to the attractiveness of a new, crisp, pristine, unhandled, fresh-out-of-the-box product, which has come right off the production line and into the gallery (the viewer discovers a certain entropic irony, however, upon closer inspection of the works: paint leaks off the sides of the paintings, messy glue stains are found on and around attachments, and chemical elements are mixed with more careless abandon than any scientific approach, causing some works to change over time). Frank has noted how television, magazines, advertising, and movies are relevant to and have influenced his work. In these paintings, the ripples of vivid, eye-popping colour pulsating across the picture plane hypnotise with a sense of targeted immediacy. Moreover, titles such as It was a stunningly beautiful evening maybe too beautiful and Mitch liked 250cc cross country bikes read like advertisement captions. By choosing these types of finishes and titles, Frank plays on contemporary society's obsession with—and susceptibility to—the new and our vulnerability to the power of appearances and advertising.

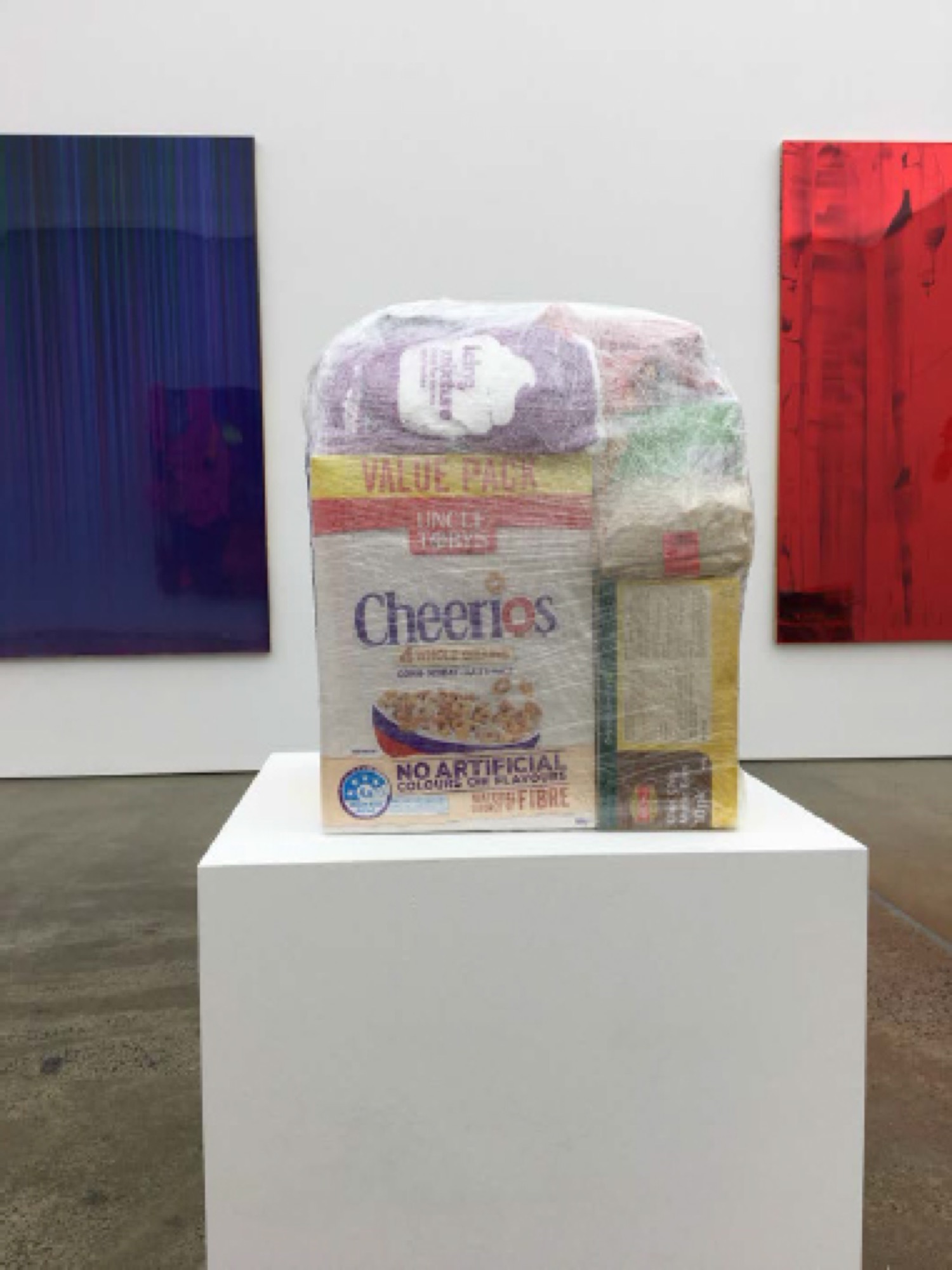

Although Frank has denied the presence of homage or reference to the art styles and movements of the past in his work, passing off any similarities as 'purely cosmetic' in an interview with Sue Cramer for his retrospective at the MCA in 2000, moments of art history do permeate his work. The 'readymade' appears in one of two sculptures included in this show, The young artist – the Devil's intolerance and the Devil's farts. I love good white people – in which heavily processed, boxed and packaged supermarket food wrapped in plastic cling wrap is elevated to “high art” by virtue of its installation on a plain white plinth (the disjointed, tongue-in-cheek, political nature of the work's title, coupled with a situational, rather than material, description of the media listed on the room sheet further emphasise a Dada tone). Is Frank commenting on or reprimanding us for our readiness to be drawn in by attractive packaging and thereby continuing to consume mass-produced products?

Frank achieves this effect in the wider exhibition, too, by appropriating commercial materials—resin, varnish, glass, epoxies, fake blood—instead of more traditional media for his paintings. These media, when removed from an industrial workshop, and displayed in the gallery, are also elevated to “high culture”.

The transformative power that Frank has granted his works thus also brings to mind the notion of l'informe (formless)—a concept developed by the French philosopher Georges Bataille ,who was involved with Breton's Surrealists in the 1920s—which seeks to deconstruct the expected hierarchies and definitions that distinguish form from content. When considering Frank's works in terms of l'informe and alongside the notion of the abject—the binary of instinctual attraction and repulsion (a notion also explored by Bataille)—it becomes clear that the artist is playing with our sensibilities. The gleaming crimson fake blood that drips down the shimmering surface of Bangladeshi, for example, is alluring, yet is also unsettling. Or disgusting. (Look around for other materials imitative of bodily substances—urine, spittle, or semen—also present in this room.) Such disruptions can, indeed, be found throughout the exhibition: mass-produced 'Chinese Hair Buns' interrupt the pristine liquid glass surface of He caught 16 year old Tristan from next door on his knees with his pants down screwing Lola his black Labrador—its title furthering the absurdist associations that Dada and Surrealist artists also sought; glitter, pretty plastic beads and fun bouncy balls float across the elegant, crystal-clear surfaces of paintings entitled Wet sheets and The scent of her period lingered longer than her contractual obligation and also engender feelings of revulsion.

Moreover, the fluid surfaces throughout the exhibition are interrupted by the systematic placement of variously juxtaposed materials (hair, resin appendages, mounds of copper sulphate crystals, masks) upon the work. This technique is taken to the extreme with the works Ramon and Guy—completely covering the surfaces of the paintings, cheap, mass-produced clown and alien masks emerge from the picture plane, a multitude of eyes stare, mouths scream and grotesque faces laugh at the viewer, confronting them with their own vulnerability and susceptibility to the material world around them.

Kylie is an art historian based in Melbourne.

Title image: Dale Frank, installation view, 2017, photography by Christo Crocker