Colony: Australia 1770–1861; Colony: Frontier Wars

Rex Butler

Colony is undoubtedly the best show the NGV has put on since Australian Impressionists in France in 2013. And I’d even say that the two shows are connected. Seriously. Both shake up our conception of what “Australia” is and perhaps even more profoundly where “Australia” is. Certainly, a number of the artists in the second half of Colony might one day be included in something called Indigenous Australians in Oxford.

Colony: Australia 1770–1861 is an extraordinary social history exhibition, tracing the European discovery and colonisation of Australia, from Melchisédec Thévenot’s 1644 map of New Holland through to Nicholas Chevalier’s 1860 watercolour of the State Library, which in the early days also housed what was called the Museum of Art. The show concludes with Chevalier’s much-loved The Buffalo Ranges (1864), the first purchase for the new gallery, and throughout Colony: Australia 1770–1861 and Colony: Frontier Wars there is a salutary, although not virtue-signalling, self-implication of the institution in the very colonial history it is now trying to unpick. Upstairs in Frontier Wars, there is a scattering of unidentified Aboriginal shields that the Museum of Melbourne is now in charge of, which at once is a heart-breaking indication of the indifference with which they have hitherto been regarded and a spectacular affirmation of their new cultural power, as spotlit emblems of colonial death and dispossession.

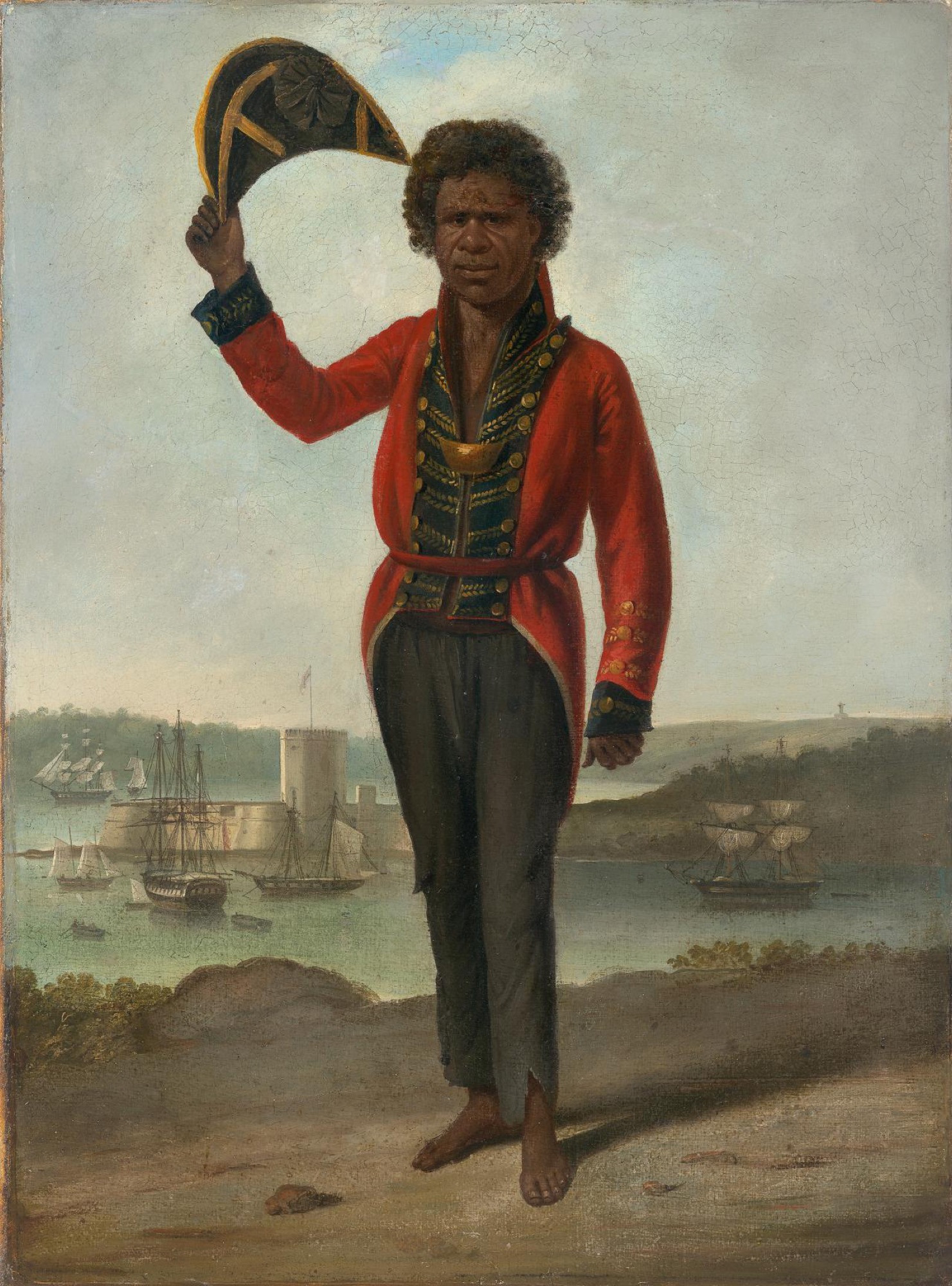

A show like Colony: Australia 1770–1861 in trying to tell the story of the early colonisation of Australia is bedevilled, of course, by the lack of Indigenous voices speaking for the other side. Put simply, the exhibition has relatively few material objects from the time by Indigenous Australians that count as works of art or even documents of social history that would narrate events from their perspective. This is the great difficulty in constructing a new story of Australia when there are virtually no recorded Indigenous voices to help testify. It is perhaps in this regard that that real innovation of Colony can be seen and the first steps in a new museology be understood to be taken. There is the usual – but crucial and comprehensive – range of images of Indigenous subjects, moving from early depictions where they are compared to local fauna through to more “sensitive” renderings by the likes of Charles Rodius and the first known photographs of Aboriginal people by Douglas Kilburn in 1847 (and, notably, to the extent possible the curators of Colony have sought to identify the subjects of these depictions and not have them as the usual anonymous “unidentified”). This exercise concludes with the curators’ coup of hanging Augustus Earle’s well-known portrait of Aboriginal leader Bungaree in red naval jacket and cocked hat across from his portraits of Captain John Piper and family, where it is hard to say who embodies and who parodies emerging colonial values.

But crucially before all this – and this, I think, is the subtly decisive gesture of the show – at the very beginning of Colony: Australia 1770–1861 we see coins found in the wreck of the Batavia that demonstrate that the Dutch were trading with Aboriginal peoples well before the British “discovery” of Australia. In an extraordinary way, it is to give Indigenous Australians a pre-British history, indeed, a pre-Australian history and agency. It is evidence that they existed not just in themselves but for the rest of the world before they became colonised Australians. Indigenous Australians are global in a way that arguably white Australians are not. And this insight cast a subtle shadow over the rest of the show. It hinted at precisely what cannot be seen, cannot be shown, to allow Colony to be staged. It pointed to a kind of Aboriginality that came before Colony, below ground level as it were, as we see an Aboriginality after Colony, up on level three. (The “globality” of the Indigenous experience was in fact the subject of a conference convened by Brook Andrew, Confronting the Frontier Wars: International Perspectives, held last weekend at the gallery.)

It is upstairs in Colony: Frontier Wars that we see what cannot be shown in Colony: Australia 1770–1861. Colony: Frontier Wars, that is, is not so much a complement to Colony: Australia 1770–1861 as its condition of possibility, what by its exclusion allows it to be represented. Of course, it was a complex decision – already much discussed – to split the exhibition into two like this, in which arguably the same story is told first from an Australian perspective and then from an Indigenous perspective. It raises the question of how the two are ever to be brought together. Or even whether they should be brought together. But before we get to that, we need to think about the space between, level two of the gallery, which is filled with several sets of Pukamani funeral poles from the Tiwi Islands, an intergenerational enterprise that began well before colonisation. The works now – and the curators would have known this – are in a beautiful dialogue with several Inge King sculptures as part of the NGV’s feminine complement to the nearby The Field Revisited exhibition, and further back in the gallery to Julius Kane’s Organic Forms (1962) and a room full of Centre Five works. In seeing the funeral poles as art, it is exactly to give Aboriginal people the voice or agency that was lacking on level 1, although it is not yet the full-throated roar that we hear on level 3.

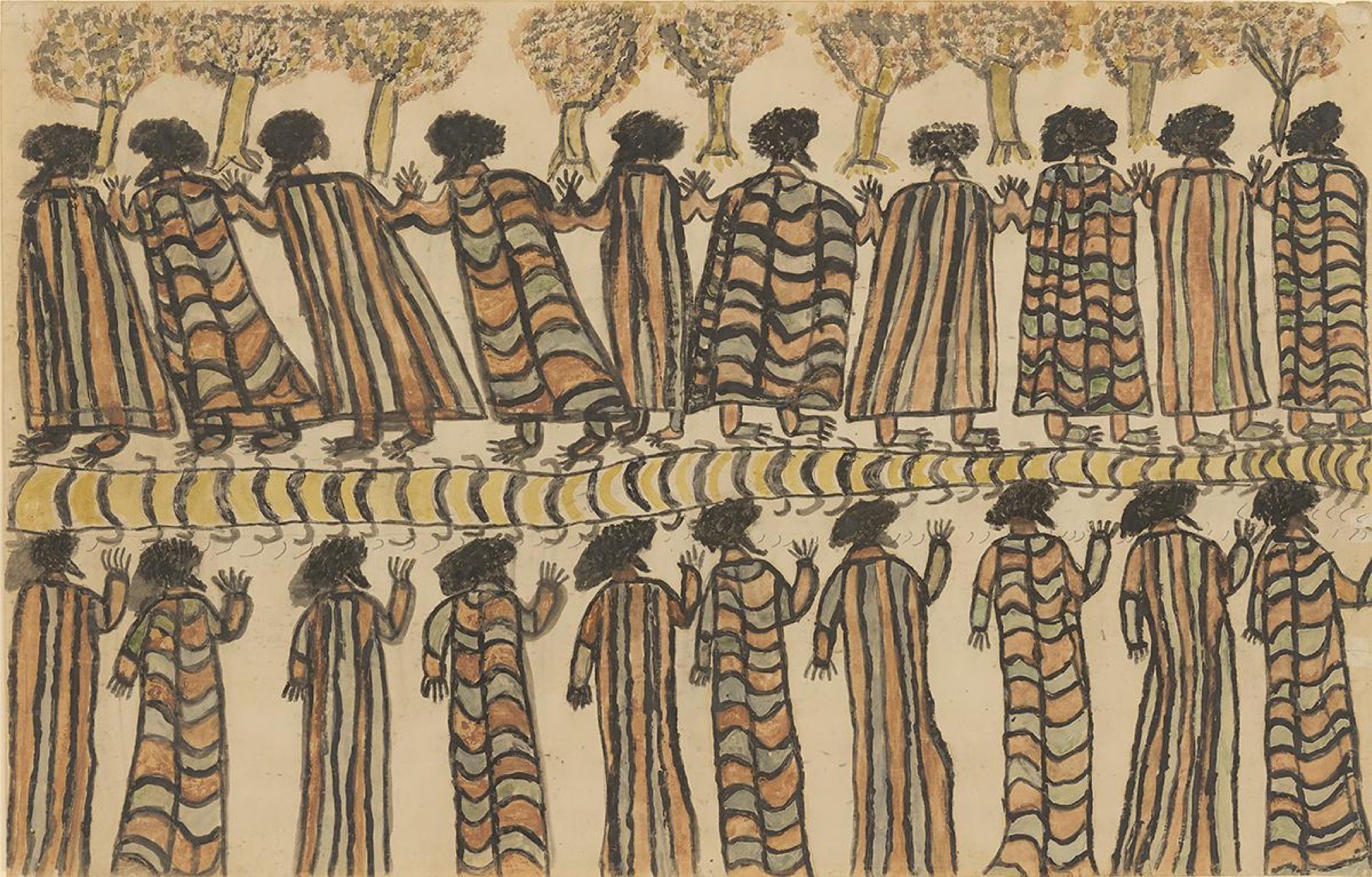

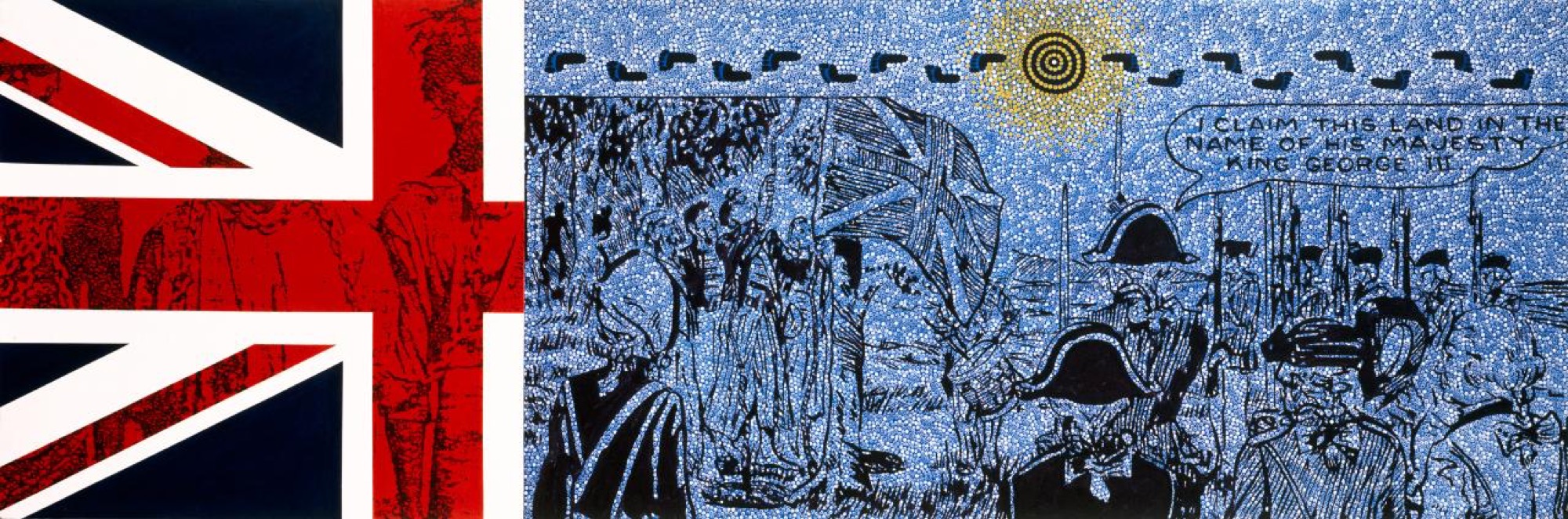

The third floor, Colony: Frontier Wars, features work by Indigenous artists taking up black-white relations in Australia, rethinking the history downstairs from an Indigenous perspective. The work, that is, is fundamentally museological in intent, often based on the same kinds of historical material as we see on the bottom floor: Christian Thompson’s well-known Museum of Others (2015), in which the artist inhabits portraits of his white colonisers; Gordon Bennett’s Terra Nullius (1989), based on a secondary school textbook of Australian history; Brook Andrews’ Gun-Metal Grey (2007), which features a series of archival photographs of Indigenous people printed on metallic foil that appear or disappear according to how one stands in relation to them. There is a beautiful dance work by Genevieve Grieves, in which the dancer Yaraan Bundle smears ochre on her face while dancing in Melbourne’s Exhibition Building that I’d want to compare to Frédéric Nauczyciel’s equally iconoclastic Red Shoes, which features a French-African man dancing in a Baroque church. The show finishes with a brilliant visual pun connecting the multiple crouched figures in William Barak’s Ceremony (1898) with the identical black men in suits of Michael Cook’s Majority Rule series (2014), which is a table-turning, Swiftian satire in which it is Indigenous Australians and not whites who occupy Australia. And the power of art, as Swift well knew, is that in saying it it becomes true.

Rex teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.

Title image: Christian Thompson, Othering the Explorer, James Cook, from the Museum of Others series, 2015–16, type-C photograph on metallic paper. Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.)