Collective Unease

Tara Heffernan and Scott Robinson

Collective Unease is staged by the now-conglomerated University of Melbourne Museums and Collections department. Announced just prior to the pandemic, the incorporation of the University’s main contemporary art venues into the department was coupled with a rebranding of the University’s diverse array of collections, archives, and galleries as the “Cultural Commons,” which has garnered some criticism. A cultural strategy and promotional framing device, the Cultural Commons is not managed by any specific faculty and appears guided by a decidedly non-academic strategy. Conforming to the increasingly dominant therapeutic rhetoric in art and academia, this marketing device’s mission statement boasts, “this is a place for you, our community, to stay connected, inspired and engaged.” In the wake of this restructuring and ongoing refurbishment of the Ian Potter Museum of Art—the University’s art museum—the exhibition finds a home in the stately cloister of the Old Quadrangle at the centre of the main campus. The title suggests the awkward relationship between the institution as a patron and its beneficiaries (artists and academics) and customers (students). The ceremonial space is draped with intriguing ornithological panels and festooned with lively video works that embellish the solemn space.

The art historian and philosopher Boris Groys writes that “there is a deep-rooted tradition in modernity…of archive bashing in the name of real life. The library and museum are the preferred objects of intense hatred.” To this list, we could add the university. Historically balanced on the fulcrum between brute reproduction of social hierarchy, the pursuit of knowledge, and the site of political radicalism, universities have increasingly incorporated the energies of protest. Installing the extracurricular at the centre of the University, the artists of Collective Unease were invited to intervene in the University’s collections with an eye to engage critically with their colonial legacies. Simultaneously, the exhibition stages an administered encounter publicising the collections they set out to critique.

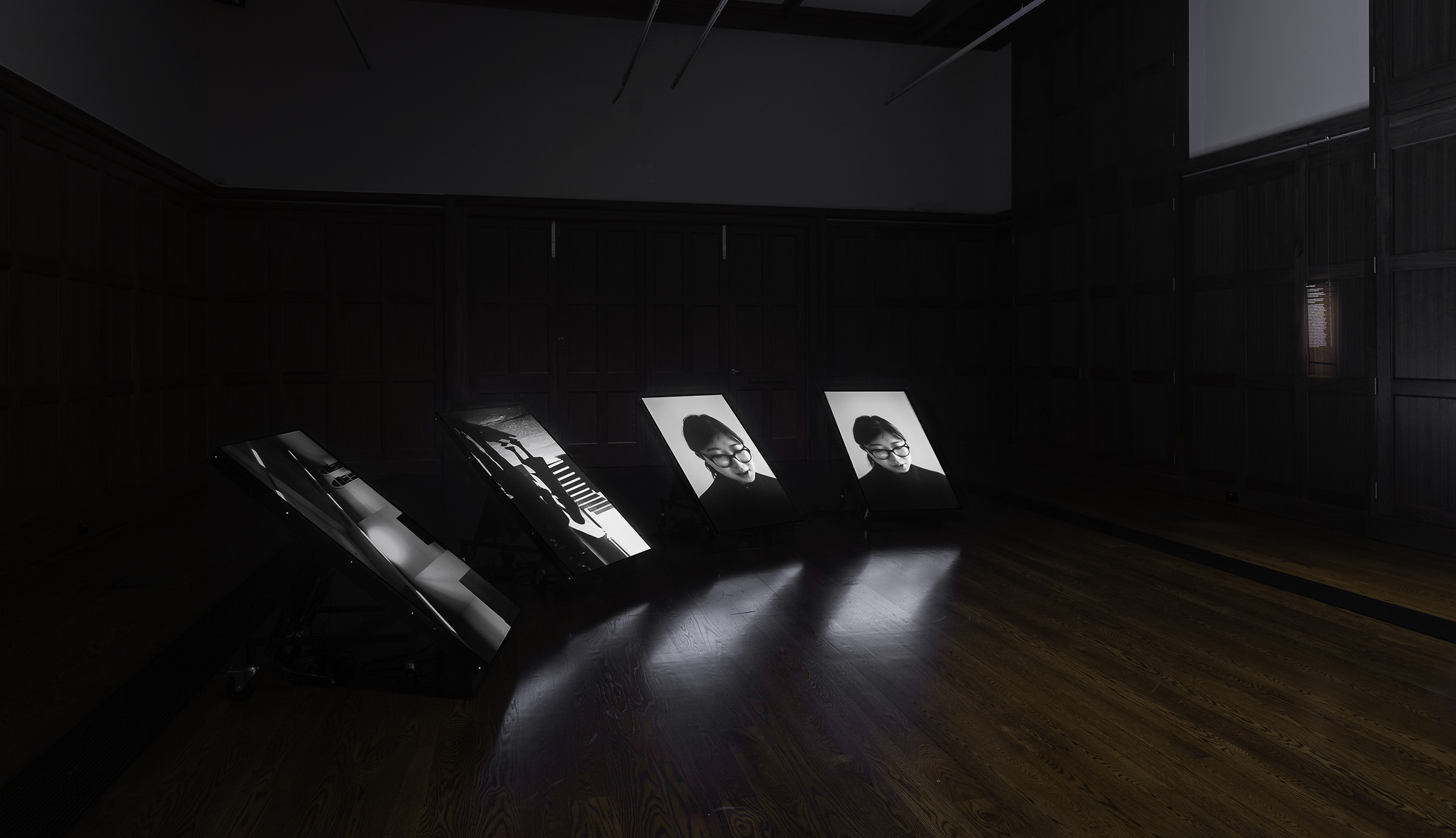

There is a palpable sense that, for these artists, the archive is a sort of trap from which they must escape by, as Groys notes, “bashing” or employing strategies of aesthetic avoidance. James Nguyen’s An Australian National Song (2022) assembles four classically trained musicians to deconstruct George Marshall-Hall’s An Australian National Song (ca. 1899), an accomplishment spread over four angled screens and nine minutes. The song is taken from sheet music housed in the Rare Books Collection. During the haphazard intervention captured in blurry footage, the rendition is memorably interrupted by expanding foam being sprayed into the bodies of the string instruments, eventually impacting their sound.

If, as Wirlomin Noongar writer Claire G. Coleman proposes in the exhibition catalogue, Nguyen’s work gleefully “assaults” the colonial “edifice,” it might have been more effective on something recognisable (as in Kate Daw and Stewart Russell’s Reverse Anthem (2021), now showing at Melbourne Now, which literally recites the existing national anthem backwards). Largely forgotten today, Marshall-Hall (1862–1915) was the first chair of music at the University of Melbourne in 1891 and quickly developed a reputation as a free thinker, socialist, and radical. He was heckled out of town by Reverend Alexander Leeper in 1898 after expressing unconventional views and defending the right to free speech in the University. No sooner recalled from obscurity, Nguyen turns this unruly figure of history into a symbol of jingoistic Australian identity, before Australia was legally founded. Marshall-Hall’s pre-Federation song suggests an anthem, but crucially a failed one, lost to the archives of an era in which nationalism meant something other than the parochial white conservative dogma it symbolises today.

Instead, Nguyen voluntaristically proposes a shibboleth in Marshall-Hall’s Song in order to undermine it. Nguyen’s An Australian National Song operates on the same premise—though without the puckish irony—as Mike Kelley’s Educational Complex (1995): if you can’t remember it, it must be traumatic. Nguyen’s anodyne array of destructive techniques aims to mute the nationalist ideology projected onto Marshall-Hall’s Song. After a brief opening recital, Nguyen’s version brushes aside the lyrics, which suggest not only a sense of colonial triumphalism in its crescendo of national foundation but also a legacy of “handiwork” passed down that we must live up to. Such rousing affects must be stifled lest we begin to long for the comfort of patrimonial belonging. Nguyen redirects our feelings through the performance of deconstruction, now itself a tired academic dogma installed at the heart of educational institutions, vacuously practising its ritual cleanse of the tradition.

Nguyen’s deconstructive strategy approaches the archive by eschewing whatever complex symbolism may be found and muting the repository of history that might be told against the grain. Nguyen expresses a destructive impulse towards musical talent, describing the intense training in the Western canon as an assimilation inflicted on the body and aesthetic taste via the rigid conventions of classical music. The demanding discipline of such training is notoriously racialised and linked to pressures experienced by migrants. Nguyen posits the standard of excellence demanded of classical musicians as false consciousness, of which he will cure them by destroying their instruments. Although Nguyen’s desire to deconstruct classical music’s reputation for rigour and austere perfectionism targets Marshall-Hall, the composer himself preferred an “interpretative sensibility…stressing emotional response as opposed to the prevailing emphasis on pure technique,” according to Thérèse Radic. He even campaigned to abolish the musical examination system and opposed the stuffy pedantry of the conservative Melbourne establishment.

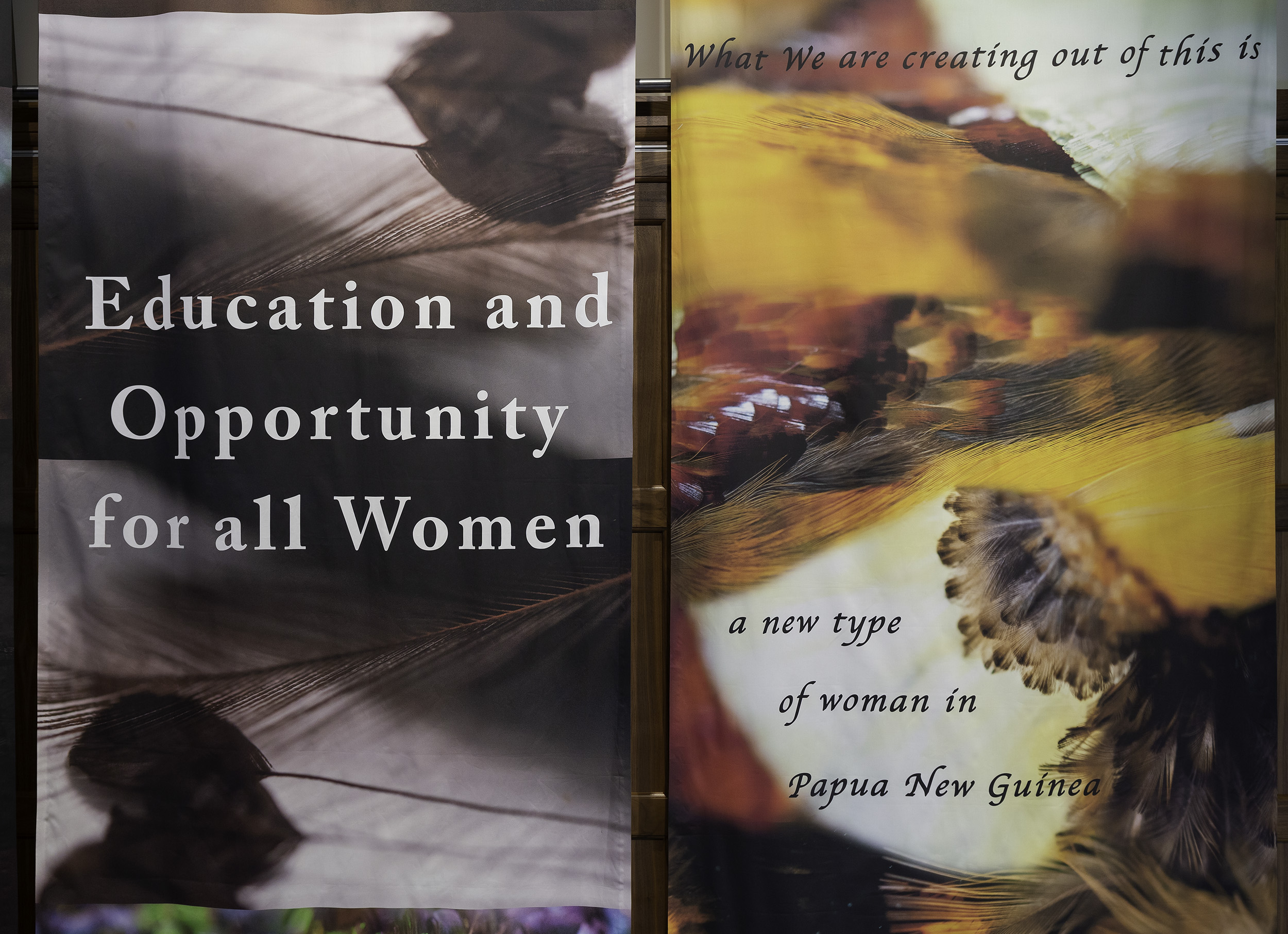

Lisa Hilli’s quiet Birds of a Feather (2022) hangs in six dimly-lit floor-to-ceiling panels installed awkwardly around an internal door. Its birdcall soundtrack is almost inaudible, drowned by the noise-bleed of the other works. Instead of the University of Melbourne collections employed by Nguyen, Hilli worked with Museums Victoria collections after finding the University’s Leonhard Adam Collection too problematic for its anthropological framing of objects. The work depicts feathers from birds of paradise species, significant to both Papua New Guinea and Dame Meg Taylor, to whom the work pays tribute. Taylor, who became Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2002, studied law at the University of Melbourne and worked as Private Secretary to the Chief Minister (later Prime Minister) of Papua New Guinea before posts as Ambassador and with the World Bank Group. Taylor’s film My Father, My Country (1989) about her father James Taylor, an Australian Patrol Officer, reckons with the tension between her roots in Papua New Guinea and subsequent global career. This context is offered by the accompanying wall text and Jocelyn Flynn’s catalogue essay “On the Wings of Mek,” rather than the work itself.

In the artwork, feathers from ornithological collections work as delicate, earnest symbols with slogans emblazoned across them drawn from Taylor’s writings, such as “Educational Opportunity for all Women.” These slogans work at a literal level, adopting the language of administered equality favoured by institutions like universities and government departments. Hilli’s Birds of a Feather aims to salvage the symbolism of Papua New Guinea’s birds from their naturalising and ahistorical representations in nature documentaries. The national bird, kumul (bird of paradise), can, according to the text on the first panel, “only fly when both its wings are strong.” According to Hilli, the bird’s wings also serve as symbols of gender equality, likely including feathers from both males and females of the species. What do these words mean alongside Taylor’s description of the absence of “a real commitment in public policy to the advancement of women,” even suggesting that women are more disadvantaged now than before national independence?

Mek is also Taylor’s ples nem (village name) and the Wahgi name for the bird of paradise species known as Stephanie’s Astrapia (named for Princess Stephanie of Belgium, wife of Crown Prince Rudolph of Austria-Hungary in 1884). Hilli focuses on Taylor brushes without exploring this dense, tangled colonial history. It is silent on the provenance of many of the collections’ specimens sourced via missionary collecting practices. They are protective and rather coy about the political histories they summon. For Hilli and Flynn, coyness implies an attempt to avoid exposure to the voracious colonial systems of knowledge accumulation. Strategic concealment unites both Nguyen’s and Hilli’s approaches to archives housed in an educational institution. These institutions have their own obfuscatory methods that cunningly preserve and dispense knowledge through a system of pay-walled stages.

The Agony and the Ecstasy (2022), purchased by the University, is the loudest work exhibited in Collective Unease. Andy Butler’s multi-channel video is presented across two large, horizontally-oriented screens, resembling a monumental open book. Butler describes the work as a reflection of “the sheer labour and athleticism and sweat and teamwork that goes into maintaining hope and optimism” in an economically uncertain, politically fraught era. Filmed in the Old Quad, with its high vaulted ceiling and parochial windows providing a wholesome collegial backdrop, the video intercuts footage of objects—paintings, sculptures, and maps—from the Russel and Mab Grimwade “Miegunyah” Collection and Samuel Ewing Collection with Melbourne University’s cheerleaders. The cheerleaders are depicted bathed in sunlight, stretching, and performing a cheer.

According to Butler, the Ivy League aesthetic of the Old Quad reflects “the power and economic inequality that is embedded within the University of Melbourne.” Butler chooses to confront this reality by juxtaposing the staid architecture and historic collections with “the over-the-top energy” of cheerleading. True, an old building is rather quiet and boring (dead?) compared to a physical sport with rhinestones and cheering (alive?). Although it’s now a competitive sport in its own right, it is difficult to disentangle cheerleading from its long-standing role of “leading cheers” for sports teams and the institutions they represent. Indeed, cheerleading champions and is championed by elite institutions. Rooted in American “game entertainment culture,” George W. Bush was a cheerleader at Yale and Franklin D. Roosevelt at Harvard. The coveted term “Ivy League,” a by-word for elitism, refers to sport. It was coined in the 1930s to describe the competitive football league assembled by Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Penn, Dartmouth, Cornell, Colombia, and Brown.

In Butler’s video, the cheerleaders chant “F-I-G-H-T for Justice and Equality” through strained toothy smiles. It would be easy to assume that this cheer serves as a heavy-handed joke on the forced optimism of PR-championed diversity washing, employing the American highschool trope of cheerleading in the vein of Mike Kelley’s extra-curricular reconstructions in Day is Done (2006). Kelley’s skits highlight the dubious conformity and presence of barely-cloaked repressions behind the rituals of educational institutions. Cheerleading provided a similar ingredient in 1990s-early 2000s mainstream media where cheerleaders sufficed as feminine marching soldiers for the debased American dream in music videos like Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” (1991), Nada Surf’s “Popular” (1996), or Marilyn Manson’s “The Fight Song” (2000). In Butler’s work, however, there is no sign that the cheer is anything but sincere. There is curatorial coherence: Butler’s cheer complements the absence of irony in Hilli’s inspirational quote banners and Nguyen’s literal performance of deconstruction. We might conceive Butler’s video as a testament to the institutionalisation of neoliberal diversity politics, once championed by radicals and now embedded in institutional branding, repeated like the school motto. Rather than an outsider (or the pseudo-outsider as artists of the very recent past seem to be), the artist is the insider: the cheer captain.

The exhibition instrumentalises the “cultural commons” strategy. It collapses the knowledge and cultural contributions of numerous faculties, collections, and experts established over a century and a half into a package that aligns with contemporary values. These artworks attempt to repurpose archives and collections for a celebration of something enabled by, but exceeding, the institution. Yet celebration has its ambivalences. The dark symbolic force of cheerleaders in mass culture, standing like a mass ornament for the institution itself, is to incite desire, envy, and violence. But while collectively their artistry and athleticism embodies the dynamism and desire for inclusion in whatever institution they represent, individually they are expended after a brief tenure. Cheerleaders paradigmatically invest their joy and energy in an institution that, ultimately, uses them up and disposes of them.

It would be too simple to merely conclude that Collective Unease offers a continuation of the very principles the artworks claim to critique: the power of the institution and the impetus to “collect” art as a means of reinforcing cultural hegemony. Particularly in the context of the move to “cultural commons” and the subsumption of the previously autonomous gallery into the Museums and Collections department, the exhibition also raises the broader question of the role of the artist in a thoroughly de-skilled era of multidisciplinary practices and art and culture’s corrosive instrumentalisation as social therapy. Here, the artists assume a bureaucratic role. Embodying Claire Bishop’s recent analysis of research-based practice, Hilli has undertaken a research project about an influential figure, presented in a clearly communicated, awareness-raising work. Intriguingly mirroring one another’s processes, both Nguyen and Butler embody the artist as administrator. They manage a group of highly skilled practitioners, yet in their work the symbolic status of this skill is determined largely by the hollow role assigned to these disciplines in mass culture. Each takes paragons in their field: Taylor’s politics and law, cheerleader’s coordinated athletic skill, the musician’s discipline and talent. Nguyen works to occlude it, Hilli to protect and celebrate at once. The ironic symbolism of Butler’s cheerleaders cannot be contained by the performance of joyous affect. Their cheers resound in the stately rooms, attempting to counter the waning faith in institutions and doing credit by the artist whose new managerial role coordinates this display of emotion.

Scott Robinson is a casual academic, writer and unionist, published in Overland, Index Journal, Arena and demos journal. Tara Heffernan is a blind art historian, currently completing a PhD at the University of Melbourne.

A prior version of this review did not clearly distinguish between the Cultural Commons and the Museums and Collections department. The Cultural Commons is a promotional strategy and cultural framework uniting the University’s diverse array of museums and collections, while Museums and Collections is a department within the University. The prior version also incorrectly suggested that Nguyen himself is depicted in his work An Australian National Song (2022) interrupting musicians by spraying shaving foam, when it is not Nguyen who sprays the foam and the foam sprayed is in fact an architectural expanding foam.