Christopher L G Hill: Meaningless is more

Giles Fielke

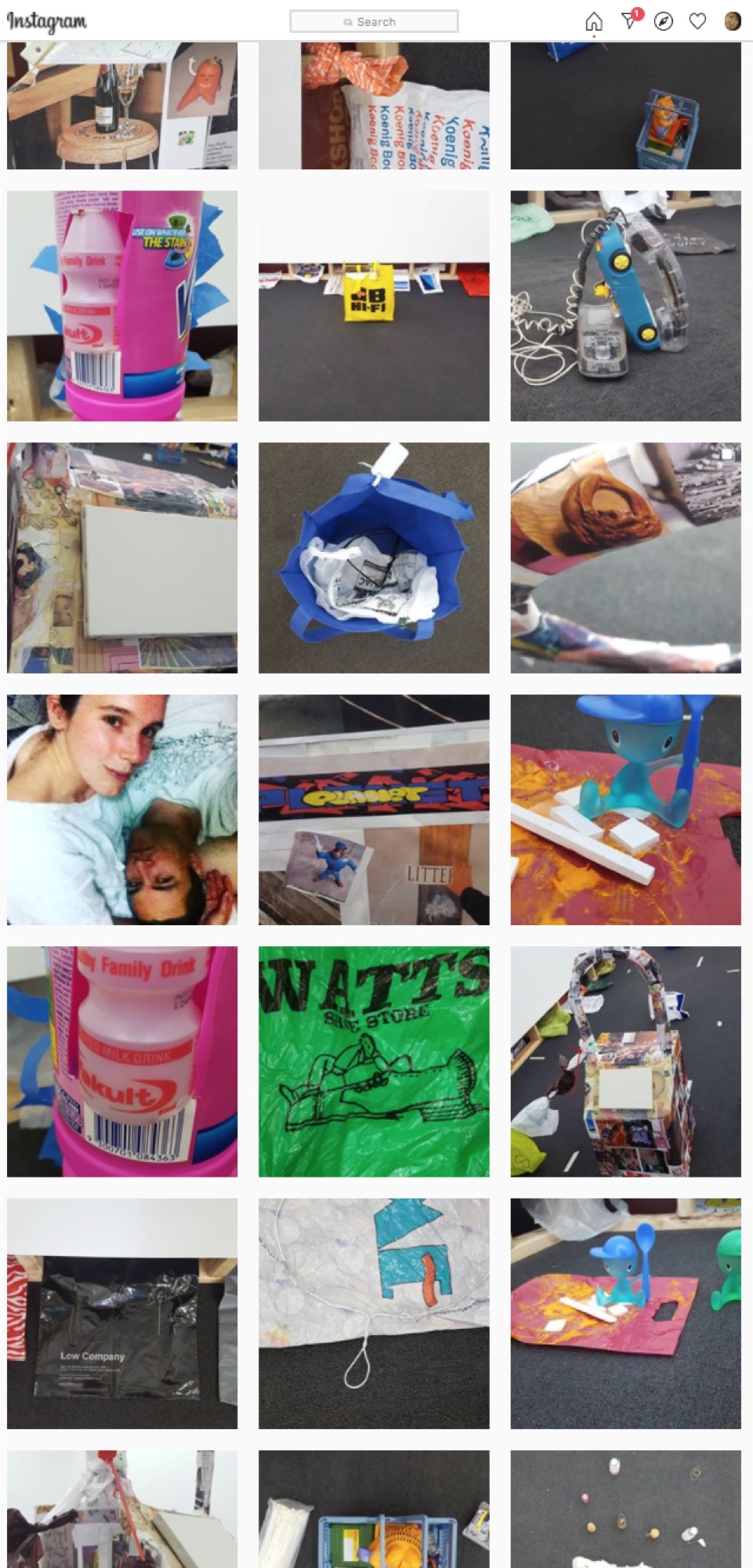

186 posts on the Instagram account christopherlghill are one part of Christopher LG Hill’s current exhibition, Meaningless is more. This online stream has been doing a lot of heavy lifting as the work depicted in the larger gallery at Conners Conners is physically inaccessible to visitors because of the COVID-19 restrictions. I have not “seen” the show. Distance is collapsed, of course, by documentation. I get the sense, however, that this is not the point of the exercise. There can be no documentation of work that solicits its documentation to instantiate itself as art. Here it is both documentation and not, art and not art.

Looking at Meaningless is more, I’m reminded of something Erika Balsom wrote recently about Karl Rove’s pejorative description of US-liberals as members of the “reality-based community,” with imagined communities instead called into being through media. Installed at Conners Conners from early August, the steady stream of images of the exhibition that Hill has seemingly taken himself and uploaded to various locations on the internet—emails, blogs, Twitter, as well as his Instagram—has not only kept Meaningless is more in the minds of Hill’s followers, but called an imaginary community into being. This community is perhaps identified as Tumblr, millennial or otherwise “online”. It’s a network that dutifully “likes” the posts, comments occasionally, uses emojis freely.

Individually personalised screens are the principal way we encounter the news, perhaps for the first time in history. But Hill’s work has always operated in the spaces between “real life” and “online” locations—in trees, in music, on social-media feeds, on the floor. As well as occupying galleries and off-site spaces, social media accounts and blogs, Hill’s playful approach to artmaking seems to follow a simple premise that all forms of media must be explored for their propensity to support art as a practice. A structure-test, perhaps, alternatively these games could be understood instead as directed to the limits of meaning. This approach borrows from the scatter technique employed by aleatoric composers; it ultimately calls upon chance as a subjectivity-less structure in a way that has now entered academic research through the formalisation of the xenotext, via poets like Christian Bök or Helen Hester. Asking an almost oxymoronic question: can art organise itself?

While it was only ever in a controversial sense that the late John Nixon was designated a “communist” artist by Rex Butler, in a related way Hill’s practice over more than a decade can only be framed by acknowledging its anarchism. In this way Hill participates in a local tradition of anarchism, as detailed by π.o. in “the greatest ode to local art history ever written”. This follows what Herbert Read called Australia’s modernist apotheosis in the Ern Malley affair: HOAXER HOISTED BY OWN PETARD. But a political-ideological position is not an artwork. And while it may become the contents for the work, ultimately it is the work in itself that remains as the work. Art is not politics. This is what Nixon, who passed away aged 70 this month, taught us. He showed how even though the idea of the work could become the content for more work—in his own case often represented by the iterability of monochrome painting and the constructivist aesthetic relocated to the East Coast of Australia after the experimentalism of punk—the concept still required its material.

Hill is indebted to this idea of the work that is no longer laboured over. Rather, it is work that is performed. Therefore, it oscillates between the score to be played and its production. Meaningless is more does not present the documentation of an exhibition interrupted by the pandemic so much as situates us in an accidentally de-activated gallery space as an imaginary location. Hill therefore participates instead in the unravelling of a tradition whereby the artwork could hang in a private salon, which provides a setting for friends and family to hold a soirée and to talk. Or else it unravels the Wunderkammern of early modernity—disrupting the established order of the world we exist in and presenting evidence of the presence of another world, perhaps many others. This fetish for display continues in our hands, on the screens of our devices. To look upon it, it seems just to gather debris.

So where is the work and what is it? In an email I received on 2 August 2020, from “______as well as untitled (Christopher L G Hill),” it is there in the “research,” that is, it is indistinct from the results of the research, with the production as just projection. Hill has said to me, in conversation, there is no work, only play. I’m not completely convinced by this but I admire his refusal to frame his work as evidence of labour as so many other artists continue to do. The objects in the gallery—located adjacent to Whitlam Place and the Condell Street Reserve and inside the neo-classical architecture of the Fitzroy Town Hall—are all collected, found, and modified by Hill, according to his desires. In this sense there is something undeniably expressive about the gesture, not so much a scattering as a careful placement of objects in the room. Again, the tension is between the scatter and the artist’s intention—this is not a xenotext.

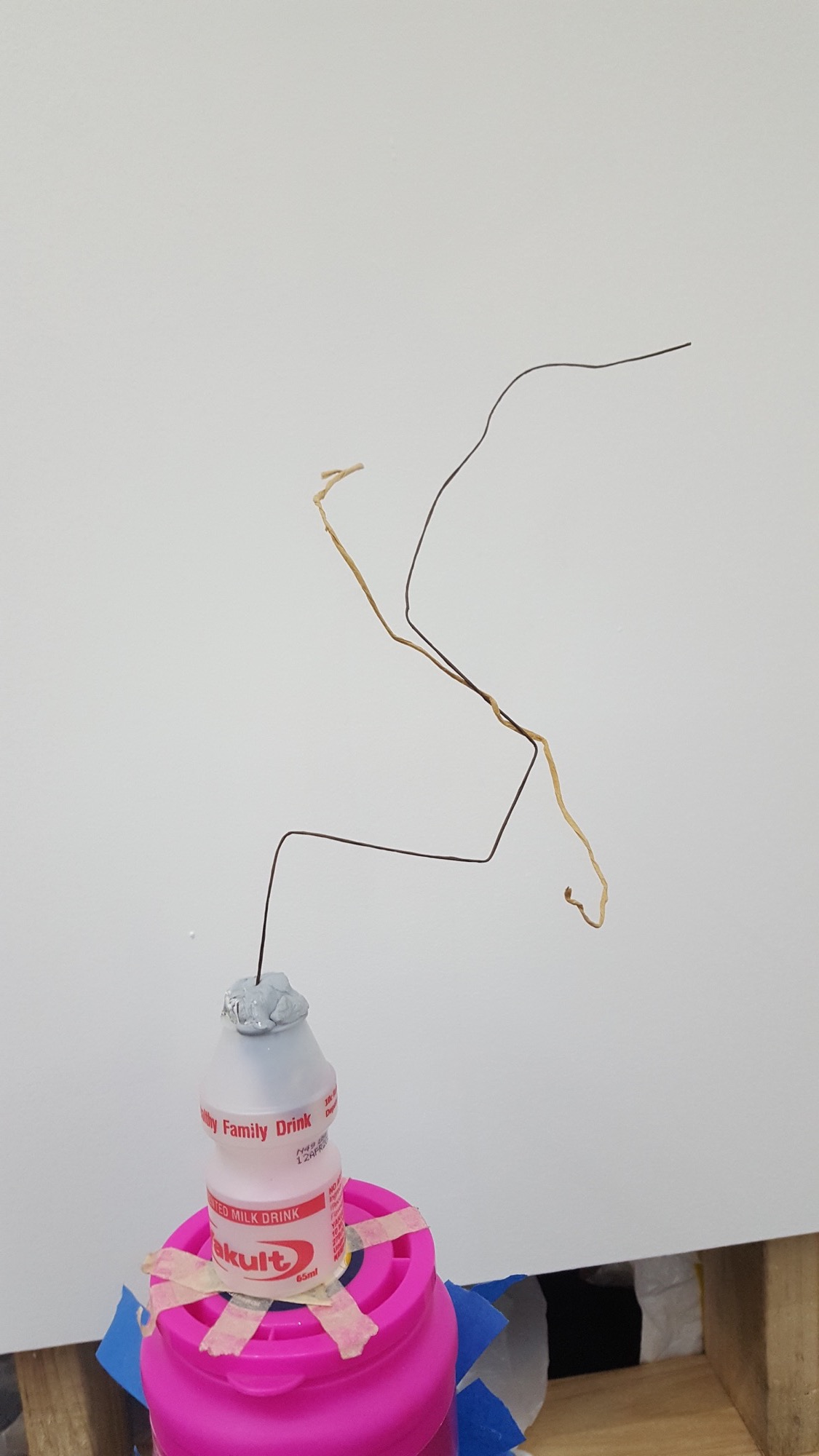

A combination lock set to 333 provides an emblem of sorts for the exhibition. A hairy sketch of it appears on Hill’s flyer for the show which also bookend the Instagram series. This is a reference to the common access lockbox that allows entry to the space. The lock, Hill has assured me, makes for an interesting chance to install work without the fussy pedantry of curators eager to ensure the appearance of the exhibition. Rather this pedantry is left to Hill. Plastic shopping bags line the nooks formed by the exposed timber studs of the floating walls of the gallery meticulously collected and archived by Hill: The Womble Family, Marks & Spencer, WHSmith, ANZ Bank. Phone-related iconography is also present throughout the exhibiton (a reference not only to a now habitual form of communication but specifically to a Petros Chrisostomou work, Receiver (2014), Hill suggests to me when I chat with him over the phone). Yakult bottles, champagne cork sculptures, cardboard, printed and secreted images and papier-mâché.

Conners Conners is a non-profit exhibition space run by an anonymous collective of “artists, art-workers, and curators”, and aimed at providing a platform for freedom (of expression?). Next door Alethea Everard presents Llocallandmarrkmarmark, a pink-monochrome object hung on the wall in the smaller gallery. References to a tradition of avant-garde art abound (Haim Steinbach’s extension of the ready-made is a constant touchpoint for Hill). As usual it is tempered somewhat by the humble “smallness” of Melbourne’s marginal art community that is for some far bigger than it seems, yet pushed further and further to the sidelines while the disaster of the shutdowns demands our constant, breathless, attention.

Apart from “bags pdf email” (a 109-page PDF of scanned plastic accompanies the exhibition), the images Hill has used seem to follow no specific logic. They are not overtly moralising paeans to the image-economy of, say, Thomas Hirschhorn or the hyper-rationalist didacticism of Hito Steyerl. Instead, Hill seems to be concerned with testing, again and again, the limits of meaning in art, at a moment when anything other than a sincere and efficient gesture can be deemed irresponsible or at best insensitive. At one point in the Instagram feed, a portrait of Hill with his wife for her birthday (artist Virginia Overell) appears within the stream of images with 249 likes and 28 comments. I’m tempted to say it arrives at the exact centre of the show. Due to its ‘filtered’ or lightly “fried” appearance (a result of its remediation), however, it doesn’t stand in contradiction to the flow. Hill and Overell themselves simply become an effortless part of the exhibition.

Hill’s obsession with the availability of used “consumables” leads me to focus on the proliferation of bags, which appear like hyper-links—reminding me of his now decade-old work Another you, a picture, a voice message, mime (2010), a poem by Hill published in print by the short-lived project y3k. Now extended as links both live and dead, relevant and irrelevant, in the form of an erotic novella/poem within, Hill’s blog entry warns us that it is open content which may offend, interest, inform, confuse, dumb down and bore. Its first word-link is Swastikas, it’s second, Anarchist symbols and its last is magic things. Bags may carry the same. Following this thought I recall the imaginary institution of a community or society as Cornelius Castoriadis would have put it. At one point Castoriadis turned his attention to the development of the mathematics of set theory or collections of things, and the editor of the journal Socialism or Barbarity questioned the limits of meaning at the abyss of its abstraction.

In an essay concerning space and number, Castoriadis remarks upon an anecdote describing the development of set theory at the turn of the 20th-century. “Dedekind wrote to Cantor,” Castoriadis recounts, “saying that he visualised sets as bottomless bags. Cantor replied that he personally pictured them rather as an abyss.” While Castoriadis’ account may be overcoded in its retelling, a related version of the story is recorded in Dedekind’s Werke, where he describes sets as closed bags, the contents of which nothing is known. That Cantor may have imagined sets as an abyss is illuminating for the fact that the abyss and the infinite are brought into a spatial relationship by the collections contained by the set. I imagine a commodity-version of this scenario, made evident by the cut—the swiping of a credit card, perhaps—which here also corresponds to the paradox of observation in systems theory, providing no determinable inside or outside. Arriving at his own bag-theory, “where to cut” is Hill’s final problem, solved by the delimited time of the exhibition. Meaningless is more exists only for a short while, imagining an ephemeral community.

The figure of the Klein bottle offers another model of the problem for locating the cut. The looping, single-sided yet three-dimensional object is what I see in the perforated pale blue plastic shopping basket that holds, amongst other things, a Garfield toy. There is no inside nor out, no document that is not also the referent. Meaningless is more provides the perfect setting for the imaginary community subjected to the repeated horrors of our news cycle today. As writer Audrey Schmidt points out in a late-night Twitter romp that I idle upon, my left hand gently padding my laptop’s track-pad while gesturing “down”, which means “up”, using my middle and ring fingers:

The worst thing about the Vogue Czechoslovakia “we should all be activists” shoot is not the lack of diversity (that’s just really moronic casting/marketing at this point), it’s that the referent just gets emptier & emptier with each new Pepsi version of commodified dissent.

The obligatory and vague ‘community’, ‘empathy’, ‘hope’ etc sentiment neatly summed up after long discussions (and being hit with a few strongly worded email templates).

And that’s just it: meaningless is more.

Dedicated to the memory of John Nixon (1949-2020). Giles is a writer and researcher of film and media art histories.