Cementa22

Anastasia Murney

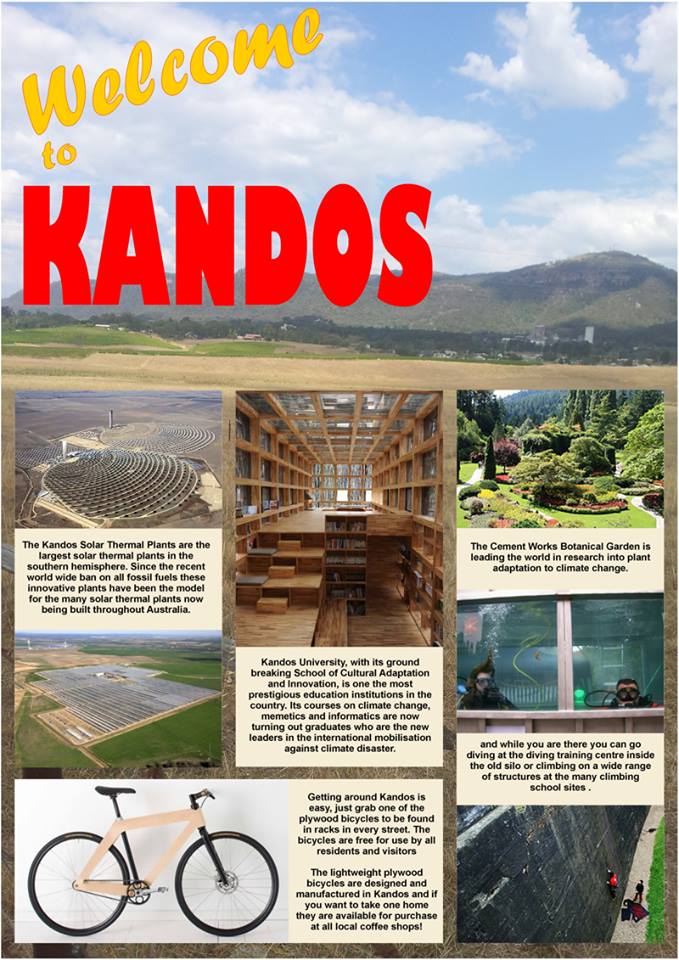

At the first ever Cementa festival in 2013, “Welcome to Kandos” posters were pasted up all over the town. Created by artist Ian Milliss, the poster celebrated Kandos’s solar thermal power station (the largest in the Southern Hemisphere), its locally-made lightwood plywood bicycles, a Botanical Garden blossoming from the defunct Cement works and Kandos University, home of the flagship School of Cultural Adaptation, training future leaders to fight against climate disaster. These posters triggered divergent responses from curious visitors and local residents, who knew such things did not exist in the town. For Milliss the poster was a serious joke—both satirical and sincere. It functioned as a provocative imagining of the Kandos that might be reborn from its sluggish post-industrial state. In fact, the Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation (KSCA) was actualised as an artistic collective in 2016, and has since been pursuing a range of initiatives experimenting with cultural change in areas such as agriculture, regional planning and food production. Both KSCA and Milliss’s poster have become central to the orienting vision of the biannual Cementa festival, now in its fifth iteration.

Before discussing this year’s festival, some context. Kandos sits just over three hours northwest of Sydney on the lands of the Dabee Wiradjuri people. In 1913, the NSW Cement Lime and Coal Company established a cement plant, and the town of Kandos developed to house the workforce. Prior to this Australia was importing cement from Germany. A single-industry town, Kandos was responsible for supplying the cement for building large-scale infrastructure projects in Sydney and the rest of New South Wales. In 2011, it was announced that the cement plant would close, no longer viable and efficient enough. Then, in 2014, came the closure of the Wallerawang power station, about an hour from Kandos and one of the biggest coal-fired stations in Australia. The loss of two big employers in the region, and the subsequent depopulation, has significantly impacted the social and economic wellbeing of Kandos and neighbouring Rylstone. Such a state of post-industrial decline characterises lots of small towns in regional areas. I grew up in one of these towns in the height of the millennium drought and the mining boom. Forbes is another few hours west of Kandos, and its establishment is synonymous with the discovery of gold in 1861. The settler-colonial identities of both towns are deeply entwined with the resources mined there. Given regional areas are vulnerable to effects of anthropogenic climate change, the question becomes: how to cultivate social and ecological adaptation and what is the role of art in this process?

Cementa22, directed by Alex Wisser, is the first iteration of the festival I have attended. Covid-19 cancelled the 2021 Cementa, so the last time it took place was in October of 2019. At this time, Kandos was struggling through severe drought, water restrictions and the onset of bushfires. People told me how tense the atmosphere was in 2019 and how the festival placed significant strain on the limited resources of Kandos. But Cementa22 seemed more serene, focusing on healing and renewal, or at least what I would call “mournful optimism” in an age of climate crisis.

The standard format of Cementa features forty artists, a lot of whom undertake residencies in the town. Each year there are fixed events such as the Saturday sound night at Henbury Golf Club and the shambolic opening performance night at the RSL Club on Friday. A new addition to the festival infrastructure was Combamalong Studios, a shed refitted as an exhibition space with a sprawling outdoor area and a pop-up bar and kitchen. It was a popular and relaxing space to hang out before and after events, something lacking from previous festivals. It was striking to note the constant presence of smoke infusing Combamalong Studios as people gathered over fire drums and meals, the benevolent presence of fire counterbalancing its apocalyptic destruction.

One of the keynote exhibitions of the festival was Carnivale Catastrophe, curated by Fiona Davies, and featuring artworks dealing with personal, collective and multispecies trauma in the wake of the bushfires impacting Kandos and the Blue Mountains. As part of the exhibition’s Living with Fire symposium, about fifty people crowded around as Uncle Peter Swain drew a large circle in the dirt clearing and gave a compelling lesson on Indigenous firestick farming—one of the most powerful moments of the festival. I was also drawn to Beata Geyer’s Landing (2022), a site-specific installation consisting of two sky-blue slabs of concrete offered as “resting places” to offer reprieve and to regain strength. Other works, such as Tom Isaacs’s Emergency Blankets (2022) and Anne Graham’s The Lost City (2022), brought together hard and soft materials—quilting and hessian sacks, felt and sandstone. This conjunction of raw industrial substances with the less visible labour of crafting offered a succinct portrait of Kandos. As artist Renee Allara told me, the town’s beloved “nannas”—see local businesses Nanna & Friends and Nanna’s Haberdashery—are less specific to a grandparenting role and more like a title that is bestowed on crafting women of the town. In this sense, the nannas are the matriarchal social fabric that underpins and outlives the economic reliance on cement and coal. What is left over after the fires? Carnivale Catastrophe suggests learning to live with fire is learning to appreciate neglected knowledges and infrastructures of care. Perhaps we need to soften rather than steel ourselves in the face of worsening climate crises.

Kandos is a microcosm of the environmental challenges facing Australia and one of these concerns the future of energy. Unlike Milliss’s large-scale vision for a solar thermal power station, some of the artworks in Cementa22 were rethinking energy on a molecular and more-than-human level. On Saturday morning, Kath Fries led a meditative walking tour around a local resident’s backyard as part of her work, Refuge (2022), which comprised bamboo structures to attract native bees. At first, I found the disciplined slowness of the walk challenging. However, in taking careful and deliberate steps, I felt the push-down and spring-up of thick grass underfoot. The distinct Kandos birdsongs sounded sharper as did the cool breeze on the back of my neck. We then drifted up the street to Tina Stefanou’s The Longest Hum (2022), an artwork that quickly became a destination (“are you going to the hum?”). People were instructed to line up along the street and fill the air with a ten-minute long collective hum, broadcast live via the local radio station. Feeling a bit awkward and bemused, I was less clear on what I was supposed to be feeling. Later on, a friend and I reflected on the experience and how we were subconsciously imitating each other’s pitch and volume—a subtle sonic dance back and forth. And on Saturday evening, Pia van Gelder’s performance-lecture, Tilting Winds (2022), spoke about straining to hear the actual sounds of a wind turbine, its machinic hum and the “secret music” on the inside. These works facilitate a closer contact with the “secret music” that supports life—bees, the crunch of grass, vibrating bodies, industrial turbines. This is also about the social context of energy creation and what it means to enter into a reciprocal exchange, how to use energy without extinguishing it from somewhere else.

Just as the Kandos University sits at the heart of Milliss’s poster, a significant part of Cementa is about taking an expansive approach to knowledge and structures of learning. While the KSCA has been pivotal to previous iterations of the festival, and is instrumental to its founding, the group was less present this year. Lleah Smith took up the main pedagogical mantle with Future School (2022), working with primary school students from the Kandos Public School. Taking place at the Scout Hall on the edge of town, the project sought to reflect on the positive changes that might be drawn from the Covid-19 experience of home-schooling and the disruption to traditional learning. On entering the hall, a group of eight students dressed in coloured jumpsuits engaging in a quiet, meditative ritual, inducting a new student into their “future school”. As we sat in a circle, Smith facilitated a discussion based on a series of questions formulated by the students: “How can we bring animals to school safely?” and “Why isn’t rest a subject in school?” The conversation made me reflect on the tacit conditioning of capitalism and how, during the height of the pandemic, I had to teach myself healthy rhythms of work and rest. One of the chief provocations of Cementa is the effort to extricate “learning” from the restrictive structures of “schooling”, which is what Smith was doing with her gentle prodding and amplification of the student’s curious questions. In fact, one of things that struck me about Cementa22 was the coexistence of practical and urgent knowledges together with poetic and whimsical propositions. This, to me, is central to the work of the festival, closing the gap between the futures we need and the material conditions of the present.

Navigating Cementa22 felt more nourishing than the extreme visual stimulation of a more conventional art festival or a biennale. The collaborative relationship between the local residents and Cementa seems to be strengthening and warming over time; the artists are increasingly no longer perceived as a “bunch of wankers” (to quote Jack Pennell of the Kandos RSL Club). The initial interest in Kandos’s post-industrial situation could be the recipe for a problematic engagement with the town. And as someone from the Central West of the state, I cringe at occasional references to Kandos as “far, far, far west Marrickville”. While friction can be productive, the line between the residents and the artists felt quite porous as the program spilled into local businesses and front gardens. Going to Kandos, I thought the tensions of the federal election would be palpable, but it was like being in a bubble. As the bubble began to break on Sunday morning, and the festival drew to a close, I started to find the disconnect reassuring. As the dust settles on a new government, we now have to contend with a Labour government that remains committed to coal and gas, and a raft of teal independents whose green credentials are tinged with a moderate blue. The risk, then, is of an environmentalism diluted into green capitalism, leaving intact the unequal impacts of climate change across race and class.

I am grateful for initiatives like Cementa that have flourished in spite of Australia’s reputation as a climate pariah and the government’s hostile neglect of the arts. The festival is a vital grassroots space devoted to the messiness of social and cultural adaptation. To this end, we need different ways of “doing politics” and horizons of hope that are not deferential to whatever government is in power. I am curious to see how the next Cementa will unfold and how it will take up the new challenges of a different—or similar—social and political climate.

Anastasia Murney is a writer and teacher living on Gadigal land. She holds a PhD from the University of New South Wales.