Aerial view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Corey Roberts.

Carrickalinga Shed

Perri Sparnon

Mortals dwell in that they receive the sky as sky. They leave to the sun and the moon their journey, to the stars their courses, to the seasons their blessing and their inclemency.

— Martin Heidegger, “Building, Thinking, Dwelling,” 1951

Carrickalinga Shed, designed by Architects Ink with landscape architecture by Landskap, is located in the coastal area of Karrakardlangga on the traditional lands of the Kaurna peoples in South Australia. The home’s use of aperture, enclosure, boundary, edge, and room arrangement guides its occupants’ awareness(es) towards an internal and external landscape. In doing so, the dwelling invites a deeper way of being present with, and connecting to, the surrounding environment beyond normative architectural gestures that privilege “the view.”

Aerial view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Corey Roberts.

The project is situated on a windy hilltop in an area with a history of agricultural clearing. Arriving at the site via a wire-fenced paddock, a stand of recent eucalypt plantings screens the expansive Saint Vincent Gulf (Wongajerla) ahead. As one curves around the hill face, the ocean is gradually revealed, and before long a simple shed-like silhouette can be seen against the grasses and pale sky.

Exterior view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

The building’s unadorned rectangular shape aligns itself plainly with the ocean, echoing the meditative compositional sincerity of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s “horizon photographs” from the Seascapes (1980–) series. It forgoes the exaggerated features common to “Australian” coastal architecture that often denote a kind of rabid energy of the activity-laden family holiday home. In these coastal designs, a predilection for demonstrative view ownership is borne out in architectural massings with soaring skillion roof lines or cantilevering box balconies over tepid porticos. These forms are symptomatic of internal plan arrangements where an upstairs “open plan” living space is oriented interminably towards the “hero” view. Contemporary houses that dominate beachside esplanades across Australia’s southern coastline in areas like Aldinga Beach (Kaurna Country), also in South Australia, or the Victorian town Torquay (Wadawurrung Country) provide familiar examples.

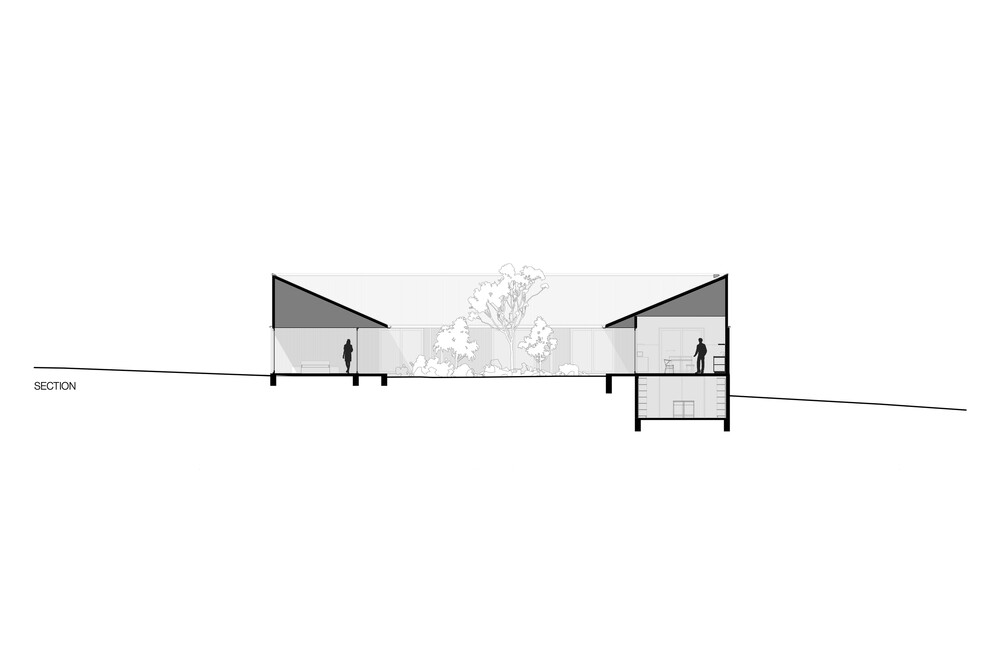

Section view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap.

Instead, this project foregrounds a concern with the more salient environmental and material qualities of its site. Corrugated steel cladding, a material typically found in nearby perfunctory sheds, forms clear linear bands across the elevations. This clarity is enhanced by externally-mounted sliding doors, which protect apertures from extreme wind loads and fire, and when retracted complete the massing. Despite its monumentality, the building’s simplicity allows it an unobtrusive and mirage-like quality within the vast landscape and horizon.

Farmhouse on the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia, 1923. Courtesy of the State Library of South Australia.

In typical Federation farmhouses, the verandah occupies a peripheral band encasing the exterior. This band relaxes the usual symmetrical room plan and facilitates episodic lingering and circulation along the edges of specifically programmed room types (hall, bedroom, dining, music room, and so on). The verandah also allows prospect over the landscape within the containment of a semi-enclosed space.

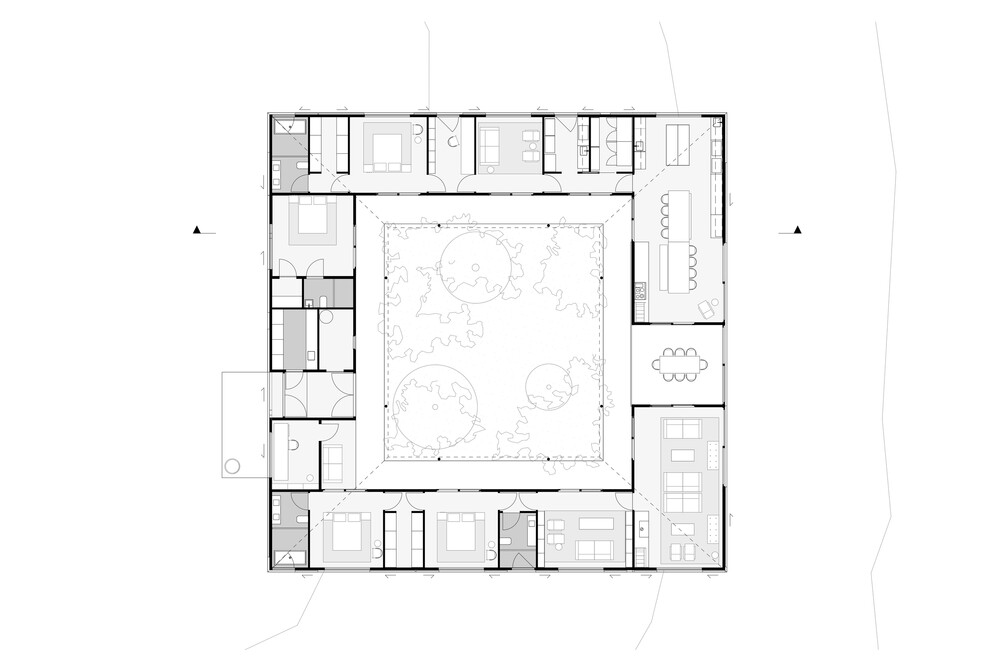

Plan view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap.

With the Carrickalinga Shed, the arrangement of the farmhouse is inverted. Instead of a semi-enclosed verandah encircling designated rooms, the central square is void, with all habitable rooms occupying the perimeter of the planted centre. Movement through these rooms is facilitated by two enfilades that run back through the northern and southern wings of the plan—a library and informal sitting room filter through to bedrooms, and then bathrooms.

View of Carrickalinga Shed courtyard, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

These enfilades equivocate traditionally expected room hierarchies, offering occupants of each room equal opportunity to dwell around the courtyard. The use of the enfilade to arrange domestic space, prevalent in other contexts throughout history, appears radical in contrast to today’s ubiquitous “open plan” domestic arrangements wherein ordinarily “private” rooms such as bedrooms and bathrooms are accessed via small interstitial corridors that tend to either entirely neuter these rooms from communal spaces, or fail to provide enough distinction so that privacy is hardly afforded at all. Here, the enfilade forms a cascade of doors that enables the perception of multiple rooms in sequence. This both defines and blurs the boundaries between them.

View of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

View of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

Open plan arrangements tend to condense the proximity of rooms so that the surface area of the architectural massing is reduced. As a consequence, some rooms—typically wet areas and service zones like bathrooms and laundries—have limited external openings.

By contrast, this plan allows each of the twenty three rooms to connect with the exterior, whether the courtyard or paddocks beyond, while twelve rooms also have dual aspects to both. Many rooms have four doors: one glazed to the farmland, one glazed to the interior courtyard, and two along the enfilade.

Interior view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

If true dwelling arises from the observance of nature’s ever-changing vicissitudes, as Heidegger suggests, then the window is perhaps the archetypal architectural element that allows connection to our surroundings for this observance to occur from an interior. The adoption of multiple glazed entries to a single room throughout the plan has the effect of dissolving the typical linearity of movement (a corridor that connects rooms), consequently enabling each room a similar interconnected nodal status (rooms connect to rooms).

Interior view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023, by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

The secondary spaces consisting of the study, library, bedrooms, and bathrooms, are not diminished in their programmatic importance due to their economical proportions but provide equal footing for the act of dwelling through affording dual aspects to both the courtyard and landscape. This uniform nodal status between rooms opposes the typical arrangements of coastal housing, wherein emphasis is routinely placed on passage to the external condition or “the view” via the common “living” and “entertaining” spaces.

Exterior view of Carrickalinga Shed, 2023 by Architects Ink and Landskap. Photo by Thurston Empson.

If, as Heidegger writes, “the nature of building is letting dwell,” it seems the circuitous and contemplative design of Carrickalinga Shed privileges this and is less concerned with “cashing in” on the imagistic qualities of its inimitable views. In clearing out the innards of the Victorian plan and reinstating a looser vegetated condition at the centre, the project affords the ordinary rooms of the coastal house plan type, so often stuffed away somewhere out the back, the architectural means to dwell. This may, in the end, be the possibility to simply “receive the sky as the sky.”

Perri Sparnon is a Graduate of Architecture based in Adelaide.